Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Biochemistry & Molecular Biology

Background: Copper-containing biomaterials are increasingly applied for bone regeneration due to their pro-angiogenetic, pro-osteogenetic and antimicrobial properties. Therefore, the effect of Cu2+ on osteoclasts, which play a major role in bone remodeling was studied in detail. Methods: Human primary osteoclasts, differentiated from human monocytes were differentiated or cultivated in the presence of Cu2+. Osteoclast formation and activity were analyzed by measurement of osteoclast-specific enzyme activities, gene expression analysis and resorption assays. Furthermore, the glutathione levels of the cells were checked to evaluate oxidative stress induced by Cu2+. Results: Up to 8 µM Cu2+ did not induce cytotoxic effects. Activity of tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) was significantly increased, while other osteoclast specific enzyme activities were not affected. However, gene expression of TRAP was not upregulated. Resorptive activity of osteoclasts towards dentin was not changed in the presence of 8 µM Cu2+ but decreased in the presence of extracellular bone matrix. When Cu2+ was added to mature osteoclasts TRAP activity was not increased and resorption decreased only moderately. The glutathione level of both differentiating and mature osteoclasts was significantly decreased in the presence of Cu2+. Conclusions: Differentiating and mature osteoclasts react differently to Cu2+. High TRAP activities are not necessarily related to high resorption.

- osteoclast

- in vitro

- TRAP

- cathepsin K

- resorption

- dentin

- copper

1. Introduction

The trace element copper (Cu2+) is involved in many physiological processes due to its ability to change oxidation states. It has been shown to promote angiogenesis [1] and osteogenesis [2] and shows antimicrobial effects [3]. Cu2+ is involved in bone formation and mineralization, as it serves as cofactor of several enzymes like lysyl oxidase, which is responsible for the cross-linking of collagen fibrils [4,5]. Therefore, copper has been widely used in the development of bone graft materials like mesoporous bioactive glasses [6,7], calcium phosphate cements and ceramics [8,9,10,11], titanium implants [12,13,14], chitosan [15,16], collagen [17] and alginate [18]. Potential bone graft materials are commonly tested for their in vitro biocompatibility and for their ability to support growth and osteogenic differentiation of osteoblasts or osteoprogenitor cells. However, there is growing interest to evaluate new bone graft materials with respect to their influence on osteoclast formation and/or osteoclastic resorption in vitro to get first information on remodeling of the materials. In a previous study we investigated Cu2+ doped brushite forming calcium phosphate bone cements (together with cements doped with other bioactive metal ions) with respect to their influence on osteoclastic differentiation and resorption [19]. It was shown, that Cu2+ had cytotoxic effects on osteoclasts at a concentration of 17.7 µM. In contrast, human mesenchymal stroma cells tolerated Cu2+ concentrations up to 250 µM without any retardation of proliferation [11]. Therefore, Cu2+ containing materials might be useful to shift the equilibrium between osteoblastic bone formation and osteoclastic resorption to increase the amount of new bone formed around a copper-releasing implant material. The high concentration of copper released by the cements in the previous study prevented the examination of its effects on osteoclastogenesis and functionality, since the cells did not survive the treatment. Investigations on the effect of Cu2+ on osteoclastogenesis and resorption are nevertheless of interest to evaluate the effect of biomaterials releasing lower amounts of this ion. The present study aimed to analyze the effect of Cu2+ on the activity of osteoclast-specific enzymes tartrate resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) and cathepsin K as well as the influence on osteoclastic resorption. Some of our preliminary investigations concerning this matter revealed a highly significant increase of TRAP activity, when osteoclasts were cultivated in the presence of Cu2+. These unexpected results encouraged us to further study the effect of Cu2+ on osteoclast functionality.

TRAP is a very specific osteoclast marker enzyme and its serum level can be correlated to bone resorption [20]. It was shown in a previous study, that the activity of TRAP and other typical osteoclastic enzymes like cathepsin K (CTSK) and carbonic anhydrase II (CA II) can be correlated to some extent to the resorptive activity of osteoclasts in vitro [21]. Therefore, we hypothesized, that the very high TRAP activity of osteoclasts in the presence of low Cu2+ concentrations may lead to higher resorption. To test this hypothesis, we differentiated osteoclasts from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) on tissue culture polystyrene (TCPS) as well as dentin slices and on cell-derived extracellular bone matrix in the presence of low Cu2+ concentrations. The influence of Cu2+ on the osteoclastic enzyme activity, expression of the corresponding osteoclastic enzyme genes and on resorption was studied.

2. Results

2.1. Cytotoxicity of Cu2+ towards PBMC and Osteoclasts

Osteoclasts are more sensitive to Cu2+ than mesenchymal stroma cells, which tolerate Cu2+ concentrations up to 250 µM without any decrease in cell number [11]. To ensure, that the investigations on osteoclast formation and functionality will be performed in a non-cytotoxic range, viability studies with PBMC and mature osteoclasts were conducted (Figure 1) PBMC showed significant loss of viability at Cu2+ concentration of 12 µM and above. In the presence of 30 µM Cu2+ the number of viable cells was reduced to 20.3 +/− 3.6%. Interestingly, mature osteoclasts tolerated Cu2+ much better. Only at Cu2+ concentrations of 20 µM and above a significantly reduced number of viable cells were detected and with 30 µM the number of viable cells was 43.9 +/−9.3 % (Figure 1). The following investigations were performed with Cu2+ in concentrations between 0 and 8 µM.

Figure 1. Cell viability of human PBMC and mature human osteoclasts after treatment with Cu2+. Luminescence-based CellTiterGlo® assay was used to determine the ATP content, which correlates with the number of metabolically active cells. Cells of two donors with each n = 3 (n = 6 in total per group) were included into the experiments. Statistic differences were calculated by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

2.2. Effect of Cu2+ on Osteoclast Number and Activity of Osteoclast-Specific Enzymes

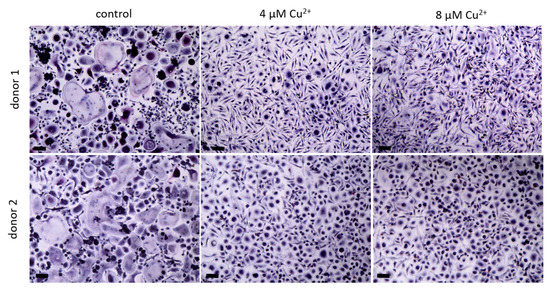

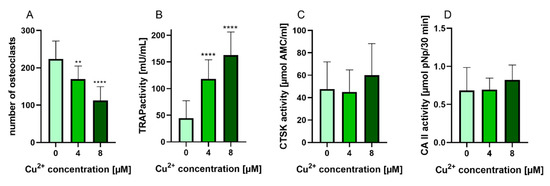

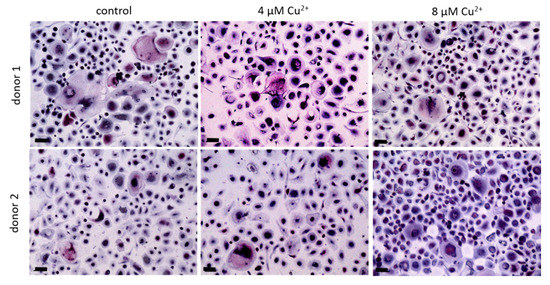

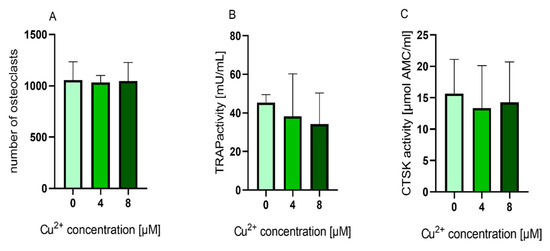

PBMC were differentiated under stimulation with M-CSF and RANKL to osteoclasts in the presence of 4 and 8 µM Cu2+. Multinucleated TRAP positive cells were formed in all groups (Figure 2) however with increasing copper concentration the number of osteoclasts decreased significantly (Figure 3A). As already found in our preliminary investigations, activity of TRAP significantly increased in the presence of Cu2+ (Figure 3B), while the activities of cathepsin K and CAII activity remained on the same level (Figure 3C,D).

Figure 2. Osteoclasts were differentiated from PBMC for 14 days in the presence of MCSF and RANKL and without Cu2+ (control) as well as under the addition of 4 and 8 µM Cu2+, light microscopy after staining of TRAP (pink) and nuclei (blue), scale bars represent 100 µm.

Figure 3. (A) Number of multinucleated TRAP positive osteoclasts differentiated from human PBMC after 14 days of cultivation, counted from light microscopic images (cells of two donors, xx images per condition) Statistic differences were calculated by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons (B) TRAP activity, (C) CTSK activity and (D) CAII activity of osteoclasts differentiated from human PBMC after 14 days of cultivation. Data of 7 different donors (each n = 5) were included into the calculation. (n = 35 in total). Statistical differences were calculated using Kruskal Wallis Test **** p < 0.0001.

2.3. Effects of Cu2+ on Gene Expression of Osteoclast Markers

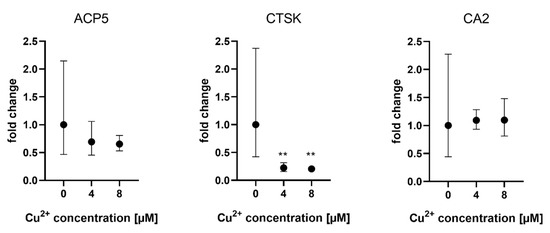

Gene expression of osteoclast markers ACP5 (TRAP), CTSK and CAII was analyzed when osteoclasts were differentiated in the presence of MSCF/RANKL and Cu2+. While TRAP and CA2 expression were not affected by Cu2+, CTSK expression was slightly reduced in the presence of Cu2+ (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Expression of osteoclast marker genes in PBMC derived osteoclasts after 14 days of differentiation. Fold changes were calculated by the ΔΔCT method and related to the samples without Cu2+. Samples of three different PBMC donors were used (each n = 3, n = 9 in total per group), mean ± upper/lower limit. Statistical differences were calculated from DCT values. ** p < 0.01.

Control values without addition of Cu2+ displayed high variances between the cells of the three different donors (see Supplemental Figure S1).

2.4. Effects of Cu2+ on Resorption

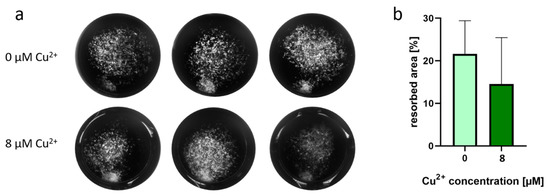

Resorption of dentin slices was not changed when osteoclasts were cultivated in the presence of Cu2+ (Figure 5). Nevertheless, TRAP activity of the osteoclasts on dentin slices was again significantly higher in the presence of Cu2+ (data not shown).

Figure 5. Representative SEM images of resorption pits after 14 days cultivation of PBMC derived osteoclasts on dentine slices (A,D) control, (B,E) 8 µM Cu2+, (F,G) without cells, scale bar represent 100 µm (A–C) and 20 µm (D–F). (G) Open source Fiji software was used to calculate resorbed area of dentin slices (cells of two PBMC donors, 24 images per group). For details see Supplemantary Figure S2. Mann-Whitney did not reveal significant differences between 0 and 8 µM Cu2+.

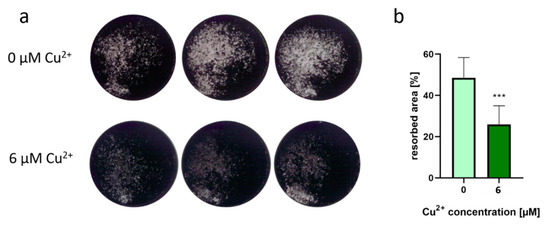

In contrast, resorption of mineralized extracellular bone matrix was significantly reduced when osteoclasts were differentiated in the presence of Cu2+ (Figure 6).

Figure 6. (a) Representative images of osteoblast-derived ECM after osteoclastic resorption in the presence of 6 µM Cu2+ compared to a copper-free control. SaOS-2 osteoblasts were cultivated for 4 weeks until a closed layer of mineralized extracellular matrix was formed in the dishes. After removal of the osteoblasts, PBMC (two donors, each n = 4 per group) were seeded and cultivated for 14 days under stimulation with M-CSF and RANKL with and without addition of Cu2+. After fixing with 4% formaldehyde, von Kossa staining was performed to stain the remaining mineralized matrix after osteoclastic resorption. Images were recorded with a Leica stereomicroscope and represent the whole area of a 48- well dish (12 mm diameter). (b) Resorbed area of all samples was calculated applying the open source software Fiji using the threshold function. Eight samples were imaged for each condition and shown as mean +/− standard deviation. Significant differences were calculated by two-tailed unpaired t-test with p < 0.001.

2.5. Effect of Cu2+ on Mature Osteoclasts

We were interested to find out, whether the TRAP activity increasing effect of Cu2+ was also detectable, when the ion was applied to cultures of already differentiated osteoclasts. Mature osteoclasts (after 10–11 days of differentiation) were detached from the surfaces, were the PBMC were originally seeded and further cultivated in the presence of MCSF, RANKL and Cu2+. Interestingly, the number of TRAP positive osteoclasts did not decrease in the presence of Cu2+ (Figure 7 and Figure 8A) Furthermore, no significant increase of TRAP activity was detected. (Figure 8).

Figure 7. Osteoclasts were differentiated from PBMC for 10 days in the presence of MCSF and RANKL, detached and cultivated for further 4 days without Cu2+ (control) as well as under the addition of 4 and 8 µM Cu2+, light microscopy after staining of TRAP (pink) and nuclei (blue), scale bars represent 100 µm.

Figure 8. (A) Number of multinucleated TRAP positive osteoclasts counted from light microscopic images (cells of two donors, 4 images per condition) Statistic differences were calculated by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons (B) TRAP activity and (C) CTSK activity of mature osteoclasts cultivated in the presence of 0, 4 and 8 µM Cu2+. Data of four different donors were included into the calculation with each n = 3 replicates per group (average +/− standard deviation). TRAP and CTSK activities were normalized to the copper free control, since the enzyme activity levels between the different donors showed high variances. Statistical significant differences were calculated by one way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test to perform multiple comparisons. * p < 0.05 compared to the control.

Resorption of osteoblast mineral matrix by mature osteoblasts was not changed in the presence of Cu2+ (Figure 9).

Figure 9. (a) Representative images of osteoblast-derived ECM after osteoclastic resorption in the presence of 8 µM Cu2+ compared to a copper-free control. SaOS-2 osteoblasts were cultivated for 4 weeks until a closed layer of mineralized extracellular matrix was formed in the dishes. After removal of the osteoblasts, mature osteoclasts, detached from suspension dishes (two donors, each n = 3 per group) were seeded and cultivated for 4 days under further stimulation with M-CSF and RANKL with and without addition of 8 µM Cu2+. After fixing with 4% formaldehyde, von Kossa staining was performed to stain the remaining mineralized matrix after osteoclastic resorption. Images were recorded with a Leica stereomicroscope and represent the whole area of a 48- well dish (12 mm diameter). (b) Resorbed area of all samples was calculated applying the open source software Fiji using the threshold function. Six samples were imaged for each condition and are shown as mean +/− standard deviation. Two-tailed unpaired t-test did not show significant differences between 0 and 8 µM Cu2+.

2.6. Effect of Cu2+ on Glutathione Levels

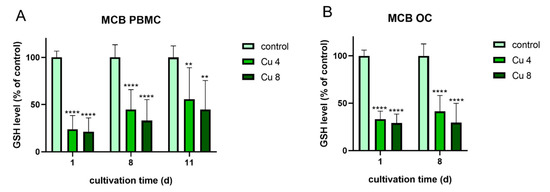

The following experiments were performed to find out, whether oxidative stress, which was induced due to the presence of Cu2+ might be in correlation to the increased TRAP activity. For this reason both differentiating PBMC and already differentiated mature osteoclasts were treated again with 4 and 8 µM Cu2+ and the glutathione levels of the cells were determined using the monochlorbimane (MCB) assay (Figure 10).

Figure 10. Glutathione levels of PBMC during osteoclastic differentiation (A) and of mature osteoclasts (B) in the presence of 4 and 8 µM Cu2+ compared to a copper-free control. Data of three different PBMC donors (each n = 3; n = 9 in total per group and time point) were included into the calculations. Statistically significant differences were calculated by 2-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

Glutathione levels of both osteoclasts and PBMC were significantly reduced in the presence of Cu2+. The highest reduction was detected for PBMC after one day of cultivation. This reduction cannot be attributed to the reduction in osteoclast number, since it was decreased only in differentiating osteoclasts (Figure 3A) and stayed stable in mature osteoclasts in the presence of Cu2+ (Figure 8A).

Interestingly, mature osteoclasts, which did not increase their TRAP activity in the presence of Cu2+, nevertheless showed a significant reduction of glutathione levels.

3. Discussion

The present study analyses the effect of Cu2+ on the activity of osteoclast-specific enzymes, their gene expression and on osteoclastic resorption. Cytotoxicity studies revealed a higher sensitivity of PBMC compared to mature osteoclasts towards Cu2+. Löffler and co-workers investigated the effect of metal ions on monocytes and macrophages. They postulated that macrophages might be better equipped against the destructive effects of metal ions, since they keep closer contact to metal ions during phagocytosis. Accordingly, Löffler et al. could show significantly higher metabolic activities of macrophages compared to monocytes at low Co2+ concentrations (Cu2+ was not included into this study) [22]. Similar effects might be conceivable for monocytes and osteoclasts in the presence of the metal ion Cu2+.

We demonstrated a significantly increased TRAP activity, when PBMC were differentiated into osteoclasts in the presence of 4 and 8 µM Cu2+ and this effect was consistently found for PBMC of more than 15 different donors. In contrast, gene expression of TRAP (ACP5) as well as osteoclastic resorption was not increased in the presence of Cu2+; resorption was even slightly inhibited by the ion. To rule out an influence of Cu2+ on the fluorimetric TRAP assay, we tested the assay with cell lysates, which were obtained from PBCM derived osteoclasts and added 10 µM Cu2+ directly to the assay. However, the TRAP activity was not increased in the presence of Cu2+, it was even decreased to around 70% compared to samples without copper (data not shown). Furthermore, our results show that TRAP gene expression was not increased, when PBMC were differentiated into osteoclasts in the presence of 4 and 8 µM Cu2+. There are not many investigations on the influence of Cu2+ on osteoclastogenesis and osteoclastic resorption in the literature. As early as 1981 Wilson and co-workers cultivated mouse calvaria tissue in the presence and absence of Cu2+ and showed a dose-dependent decrease of osteoclastic resorption [23]. In 2002 Zhang et al. demonstrated an inhibition of resorption, when rabbit osteoclasts were cultivated on bone slices in the presence of 1 µM Cu2+ [24]. Finally, the group of Pamela Habibovic deposited different elements, including copper to calcium phosphate films in a biomimetic approach. They demonstrated a significantly reduced resorption when primary rabbit osteoclasts were cultivated on copper-containing films [25]. All these studies did not analyse TRAP activity, however, a reduced resorption in the presence of Cu2+ was also demonstrated in our study, but only in the case of osteoclasts, which were treated with Cu2+ during osteoclastogenesis from PBMC and only towards extracellular bone matrix (Figure 6). Besides differentiating osteoclasts, which were formed from PBMC, also mature osteoclasts were involved. In a previous study [26] we compared different surfaces for the detachment of osteoclasts, which generally resulted in relatively low yields of detached osteoclasts. Heinemann and co-workers also report difficulties in detaching osteoclasts, which were formed in vitro on commonly used cell culture surfaces and propose special temperature-sensitive dishes for osteoclast detachment [27]. In the present study, we tried ultra-low attachment cell culture flasks for formation and detachment of osteoclasts. Both differentiation time and osteoclast yield were considerably increased on these surfaces compared to other cell culture surfaces. PMBC were able to attach loosely to the surfaces, which might have promoted their ability to migrate and fuse. After being formed, the multinucleated osteoclasts could be easily detached just by adding low concentrations of buffered EDTA without using a cell scraper. Interestingly, in our study the resorption was less affected, when Cu2+ was added to mature osteoclasts, indicating an effect of Cu2+ on osteoclast formation rather than osteoclast function. However, the above cited study of Yang et al. also used mature osteoclasts, directly isolated from bone and found a significantly decreased osteoclastic resorption.

The central questions of this study are how Cu2+ affects TRAP activity and why both TRAP gene expression and osteoclastic resorption are not increased in the same way. TRAP activity is regulated in a redox dependent pathway: the active centre contains two ferric ions, and the enzyme is active, when one of them is in a reduced state [28]. Copper as redox active metal ion is able to generate reactive oxygen species, which could change the redox state of TRAP and therefore activate this enzyme. This would be in line with the unchanged TRAP mRNA expression in the presence of Cu2+, indicating a regulation on protein level. However, it has been shown that copper is a potent inhibitor of TRAP activity with a Ki of 6.8 µM [29] which is in line with our observation of a reduced TRAP activity when copper ions are added directly to the assay (see above). It has been shown in numerous studies that copper can induce oxidative stress in biological systems [30,31]. Intracellular antioxidant substances protect cells from highly reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated by different redox reactions. The most prevalent cellular protective antioxidant is the thiol-containing tripeptide glutathione, which is present in all cells in high concentration [32]. Different methods were proposed to quantify the level of reduced glutathione (GSH) in cells. Among these, the fluorometric monochlorbimane assay [33], which was optimized by Capek, and co-workers is a useful method since the reagent is able to penetrate through the cell membrane and to directly react with intracellular GSH [34]. We demonstrated a significant reduction of GSH levels in both PBMC and mature osteoclasts, indicating, that the cells suffered from oxidative stress in the presence of low concentrations of Cu2+. It has been early postulated, that increased ROS levels support osteoclastogenesis and TRAP activity [35,36]. Later, different groups reported an elevation of intracellular ROS level during stimulation of monocytes with RANKL and reduced osteoclast formation when the cultures were treated with antioxidants [37,38]. ROS generated through the presence of Cu2+ could therefore have increased TRAP activity in our experiments. However, why did the increased TRAP activity not imply an increased osteoclastic resorption? It has been shown before, that TRAP activity does not necessarily correlate with osteoclastic resorption. The function of TRAP in osteoclasts is proposed to further degrade collagen fragments, which were initially digested by cathepsin K, and it was shown, that the enzyme itself is able of producing ROS for these degradation processes [39]. It has been shown, that TRAP activity is rather a marker for osteoclast number than for osteoclast resorptive activity [40,41]. In addition, our own investigations displayed a strong dependency of TRAP activity from the composition of the resorbed material [21]. In the case of Cu2+ or Cu2+ containing biomaterials it can be concluded that the highly significant increase of TRAP activity is not reflected by an increased osteoclastic activity. Quite the opposite, a reduction of resorptive activity of osteoclasts in vitro was observed in the presence of Cu2+ for osteoclast, differentiated from PBMC in the presence of extracellular bone matrix (Figure 6). The reduced number of osteoclasts in this experimental setup (Figure 2 and Figure 3A) can explain this effect. In contrast, the addition of Cu2+ to already differentiated osteoclasts did decrease neither osteoclast number nor resorptive activity (Figure 8A and Figure 9).

Consequently, Cu2+ released from potential implant materials in concentrations below 10 µM does not induce increased osteoclastic resorption. As shown in our study, higher concentrations of Cu2+ are cytotoxic to osteoclasts and PBMC in any case, while mesenchymal stromal cells were shown to tolerate Cu2+ concentrations up to 250 µM [11]. Therefore, doping of bone graft materials with low amounts of Cu2+ could shift the equilibrium between bone formation and bone resorption around the implant.

In a conclusion, Cu2+ has a substantial influence on the formation of osteoclasts from PBMC. While considerably less multinucleated osteoclasts are formed in the presence of even low amounts of Cu2+ (4 and 8 µM), the activity of the most specific osteoclastic enzyme, TRAP, is significantly increased. In this study, we could show that this increased TRAP activity is neither based on an increased gene expression nor contributed to an increased osteoclastic resorption. We hypothesized, that ROS, generated by Cu2+ induced the detected high TRAP activity. In contrast to PBMC mature osteoclasts are less sensitive to Cu2+. Higher Cu2+ concentrations were necessary to reduce cell viability of mature osteoclasts and low Cu2+ concentrations did not trigger the activity of TRAP.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms22052451

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!