The milk fat globule membrane (MFGM), the component that surrounds fat globules in milk, and its constituents have gained significant attention for their gut function, immune-boosting properties, and cognitive-development roles. The MFGM can directly interact with probiotic bacteria, such as bifidobacteria and lactic acid bacteria (LAB), through interactions with bacterial surface proteins. With these interactions in mind, increasing evidence supports a synergistic effect between MFGM and probiotics to benefit human health at all ages.

- gut microbiota

- infant formula

- milk fat globule membrane

- dairy foods

- interactions

1. Introduction

The milk fat globule membrane (MFGM) is the structure comprised of lipids, membrane-associated proteins, and carbohydrates in the form of glycoconjugates, which surround every fat globule secreted in milk during lactation of mammals. The beneficial impacts of the bovine MFGM have been well-established [1]. In recent years, infant formula companies have begun to include MFGM ingredients in their formulations for its effects on cognitive development and gut maturation [2][3]. Furthermore, the focus on understanding how MFGM affects the gut microbiome of developing infants is gaining momentum. The current evidence demonstrates that MFGM supplementation increases the abundance of beneficial bacteria, such as bifidobacteria and some species of lactic acid bacteria (LAB), which is associated with a reduced risk of several diseases, including type I and type II diabetes, hepatitis B, and obesity (previously reviewed in [1]). However, the mechanism by which the MFGM imparts its benefits is much more poorly understood. In addition to the benefits of MFGM consumption, probiotics and their positive outcomes go beyond intestinal and immunological health by also directly impacting cognitive function.

2. Interactions of Bifidobacteria, LAB, and MFGM in Dairy Food Matrixes

Milk and dairy products are the most popular matrices for the dietary delivery of LAB and bifidobacteria to humans, but little is known about how the MFGM interacts with and impacts bacterial cells. Moreover, no mechanism has yet been fully described to explain this interaction. The knowledge of the latter could very well contribute to the development of more efficient dairy foods, with an increased impact on human health. Since the middle of the last century, the inclusion of LAB in fermented foods has generated a revolution in the processing, production, and consumption of foods. Since that time, several starter cultures have been developed for fermentation and direct inoculation in food matrices. A starter culture is defined as a group of microorganisms that are inoculated directly into the food matrix with the intention of providing desirable changes in the final product [4]. One application of the interactions between LAB and MFGM is their utilization for the cryoprotection of stock and starter cultures. Bacterial freezing processes decrease the cell viability, damage the bacterial membrane, and reduce their functionality. The supplementation of 0.5% MPLs in acid whey-based media has been reported to protect LAB from freeze/thaw cycles [5]. Starter cultures also induce changes in a final product, including improved sensory and nutritional properties and compositional changes for the preservation of foods, as well as an added economic value [6]. The reactions amounting to these changes are directly related to the presence and composition of the carbohydrate, protein, and lipid components [7].

The interaction between MFGM and LAB and bifidobacteria is an adhesion phenomenon driven primarily by the bacterial surface properties. It is a very complex relationship that depends on many factors, including, but not limited to, strain genotype and phenotype and bacterial biochemistry, such as environmental conditions, cell viability, and metabolic activity. It is also impacted by the dairy matrix composition, water content, and processing strategies used upon the foods. Hence, there is no current set of rules or guidelines to predict whether the interaction will occur in all food matrices or under what mechanism; it should be reviewed case-by-case. In general, bacterial adhesion occurs in two steps: the first contact with the substrate is nonspecific and governed by reversible interactions such as electrostatic, van deer Waals, and Lewis acid–base. This step is followed by nonreversible and specific interactions involving adhesion factors, complementary receptors, surface appendages, teichoic and lipoteichoic acids, and EPSs from the cell envelope [8][9]. Given these phenomena, we should expect an attachment of LAB and bifidobacteria to the MFGM to occur in the same manner.

In dairy products, we now know that LAB and bifidobacteria are preferably associated with the fat/protein interfaces in cheeses at first, and after a period of aging, they have been found embedded in the MFGM or inside the fat globules when they exert their lipolytic activity [10][11][12][13]. Recently, a 45.9-kDa phosphoesterase with activity toward PL was isolated and characterized from Pediococcus acidilactici [14], which indicates a variety of lipolytic enzymes found in LAB and their affinity not only to milk fat but to MPL as well. Other research suggests that LAB and bifidobacteria may have additional activity beyond lipolysis of the MFGM components. For example, lactobacilli isolated from cheese has been shown to grow and utilize the monosaccharides present in MFGM glycoconjugates [15], which may alter the flavor development in cheeses [16].

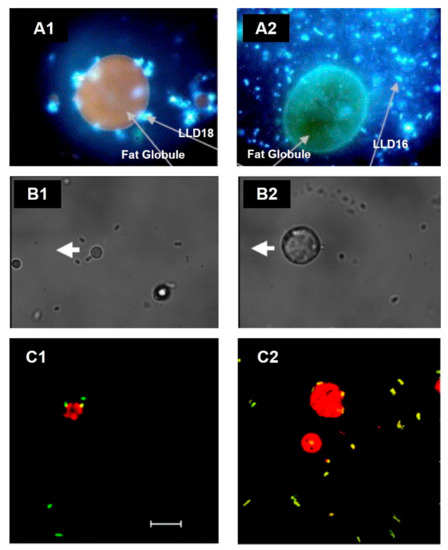

In fresh cream, the direct association of LAB to fat droplets was informally reported in 2008 [17], and ever since, strains such as Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis subv. Diacetylactis [18] and L. reuteri SD2112 and T1 have been shown to attach directly to the MFGM in the surface of fat globules (Figure 1). Moreover, Brisson and colleagues were able to establish that the mechanism of adhesion occurs through specific connections with the bacterial surface proteins [19].

Figure 1. Association of lactic acid bacteria (LAB) with the MFGM in cream imaged by microscopy. (A) Fluorescence microscopy images of L. lactis ssp. lactis subv. Diacetylactis. (A1) Variant 18 (LLD18) is clearly attached to the MFGM, whereas (A2) variant 16 (LLD16), in comparison, is not. Adapted with permission from Ly et al. (2006) Copyright 2006 Elsevier Ltd. [18]. (B) Optical tweezer force images of L. reuteri SD2112 attached to the MFGM. (B1) Bacterial cells fixed to the cover slide, whereas (B2) shows the experiment when the MFGM is attached to the cover slide. The thick white arrow shows the direction of the microscope stage travel. Adapted with permission from Brisson et al. (2010). Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society [19]. (C) Confocal laser scanning images of (C1) L. reuteri SD2112 and (C2) L. reuteri T-1 in raw cream. Scale bar = 10 µm. Adapted with permission from Brisson et al. (2010). Copyright 2010 American Chemical Society [19].

Simple models have shown that many strains of LAB directly bind to MFGM components. Guerin and colleagues used atomic force microscopy to identify that Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus GG (ATCC 53103) binds MFGM isolated from raw cream using functionalized probes, and moreover, they identified that the adhesion occurs through the interaction of SpaCBA pili in the bacterial cell wall [20].

It is clear that many strains of LAB, in fact, interact with the MFGM; however, the identification of the specific components from the MFGM that interact with these bacteria are not well-known to date. We can hypothesize, based on the literature, that LAB are prone to bind primarily to glycans of the MFGM proteins, such as PAS6/7 and mucins, due to their high degree of glycosylation (approximately 10% and 60%, respectively) [21][22][23][24]. MUC1 is resistant to gastrointestinal digestion, likely due to its sugar moieties, including fucose, galactose, mannose, N-acetylgalactosamine, and N-acetylglucosamine, among other sugars, which sterically protect it from proteolytic degradation [24][25]. PAS6/7 has been previously reported to retain its ability to bind bacteria due not only to its glycosylation but, also, its association with lipids and, specifically, PS [21][26]. A study used the sucrose density gradient to show that six strains of L. reuteri isolated from various dairy products bind MPLs from the MFGM [27]. L. reuteri showed greater interactions with MPLs compared to Pediococcus lolii, suggesting that these interactions can vary at the genus and species levels. In addition, it was found that some of the strains contained an increased relative expression of surface-binding promoting genes CmbA, Cnb, and MapA with the addition of 1% (w/v) of MPL. Mucus adhesion-promoting protein (MapA), the collagen-binding protein (Cnb), and a putative sortase-dependent cell and mucus binding protein A (CmbA) have been shown to promote the adhesion of bacteria to intestinal epithelial cells [28][29][30][31].

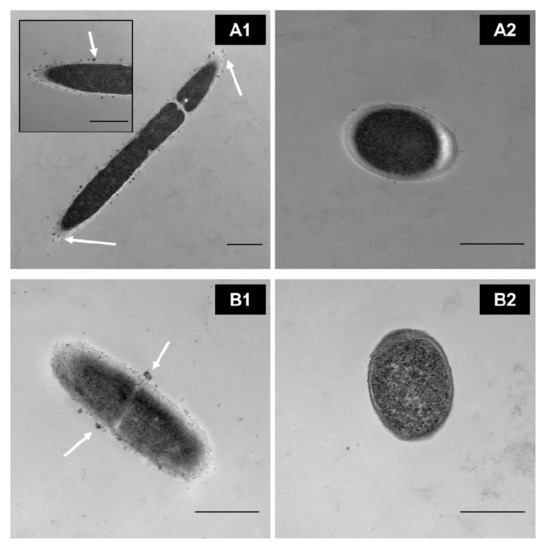

In our research group, through transmission electron microscopy (TEM), we identified that MPLs from the MFGM in simple models bind directly to the surface of some Lactobacillus (Figure 2(A1,B1)) in a strain-dependent manner during cell growth rather than internalizing them for further metabolism. This, in turn, affects the parameters of the bacteria, such as the growth rate; cryotolerance; surface hydrophobicity; ζ-potential; and adhesion properties such as expression of adhesion factors and mucus-binding proteins [27][31][32] (Ortega-Anaya, J., Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA; personal communication, 2020). In complex matrices such as milk and dairy products, the interaction, as well as the outcome, is expected to be more complex.

Figure 2. TEM images of washed cells grown in a defined medium supplemented with 0.5% of MPL. (A1) Lactobacillus delbrueckii vs. (A2) control. (B1) Lactiplantibacillus plantarum vs. (B2) its control. Scale bar = 500 nm. White arrows indicate MPL accumulation at the cell surface(Unpublished images, Ortega-Anaya (2020) Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA; personal communication).

3. Evidence of Improved Health with Combined Probiotic and MFGM Supplementation

Although the exact mechanism of interaction between probiotics and the MFGM has not been fully elucidated, the evidence of the synergistic effects upon the combined supplementation of these functional ingredients suggests beneficial outcomes in both in vitro and in vivo studies, including studies in infants (summarized in Table 1).

Table 1. Purported health benefits of combined probiotic and MFGM supplementation.

|

Ingredient |

Microorganism(s) |

Model |

Experimental Design |

Key Findings |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Bacterial Survival and Adhesion |

|||||

|

Whey-derived MFGM (MFGM-10 Lacprodan®) |

L. rhamnosus GG (LGG) |

Male, 6-week-old BALB/c mice |

Oral gavage of 0.1 mL MRSC media, MRSC with 5 g/L MFGM-10, MRSC with LGG (5 × 107 CFU/mL) or MRSC with 5 g/L MFGM-10 and LGG (5 × 107 CFU/mL) for 3 days |

|

[32] |

|

MFGM-derived MPL concentrate |

Lacticaseibacillus casei OSU-PECh-C; Lactobacillus acidophilus Musallam2; L. plantarum subsp. plantarum TW14-1; L. delbruekii OSU-PECh-3 |

Gold (Au) Sensor; Caco-2/HT29-MTX |

Examined the adhesion phenomena of 4 strains in the presence or absence of 0.5% (w/v) MPL to A) a gold sensor using a Quartz Crystal Micrograph with Dissipation (QCM-D); B) TEM; and C) intestinal cell culture |

|

[33] |

|

MFGM-derived MPL concentrate |

P. acidilactici OSU-PECh-L; P. acidilactici OSU-PECh-3A; L. plantarum OSU-PECh-BB, L. reuteri OSUPECh-48; L. casei OSU-PECh-C, L. paracasei OSU-PECh-BA; L. paracasei OSU-PECh-3B |

Caco-2 |

LAB strains grown with or without 0.5% (w/v) MPL were characterized by functional properties and their adhesive ability to fully differentiated Caco-2 cells |

|

[31] |

|

MFGM extract from butter serum |

L. rhamnosus GG (LGG) |

Caco-2 TC7 |

LGG was exposed to 5 mg/mL MFGM extract for 1 h and applied to intestinal cells (1 × 109 CFU/mL) |

|

[20] |

|

MPL-rich milk protein concentrate (Lacprodan® PL-20) |

B. longum subsp. infantis ATCC 15697 |

HT-29 |

Exposed bifidobacteria to MFGM ingredients for 1 h and measured adherence of bacteria to fully confluent cells after 2 h incubation using plate count method |

|

[34] |

|

Whey-derived MFGM (MFGM-10 Lacprodan®) |

|||||

|

Buttermilk fraction (BF) |

|||||

|

Nutrient Absorption, Mucosal Immunity, and Gut Barrier Function |

|||||

|

MFGM-derived MPL concentrate |

L. delbruekii subsp. bulgaricus 2038; S. thermophilus 1131 |

Male Sprague-Dawley rats |

Orally supplemented rats with SM, MPLs alone or either of these in fermented milk |

|

[35] |

|

Whey-derived MFGM (MFGM-10 Lacprodan®) |

L. paracasei subsp. paracasei F19 (F19) |

Infants (21-days−4-months old) |

Double-blind RCT for an infant formula supplemented with MFGM (5 g/L prepared formula) or F19 (1 × 108 CFU/L) |

|

[36] |

|

Unspecified MFGM fraction |

B. animalis subsp. lactis BB-12 (BB-12) |

HT-29Cl34 (NF-κB reporter cell line); 28-day-old mice |

Used reporter cell line to measure NF-κB activation in response to BB-12 (1 × 106 or 1 × 107 CFU/mL) and/or MFGM (50 μg/mL or 100 μg/mL) and LPS challenge (100 ng/mL); For in vivo mouse study, administered BB-12 (1 × 108 CFU/day), MFGM (0.6 mg/g of body weight/day), or both BB-12 and MFGM orally for 1 or 4 weeks |

|

[37] |

|

Neurodevelopment and Cognitive Function |

|||||

|

MFGM components |

B. infantis IM1; L. rhamnosus LCS-742 |

12-month-old infants |

Double-blind RCT (COGNIS study) for a novel infant formula containing bioactive ingredients, including MFGM [10% of total protein content (w/w)] and probiotics |

|

[38] |

|

MFGM components |

B. infantis IM1; L. rhamnosus LCS-742 |

4-year-old infants |

Double-blind RCT (COGNIS study) for a novel infant formula containing bioactive ingredients, including MFGM [10% of total protein content (w/w)] and probiotics |

|

[39] |

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/microorganisms9020341

References

- Anto, L.; Warykas, S.W.; Torres-Gonzalez, M.; Blesso, C.N. Milk Polar Lipids: Underappreciated Lipids with Emerging Health Benefits. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1001.

- Snow, D.R.; Ward, R.E.; Olsen, A.; Jimenez-Flores, R.; Hintze, K.J. Membrane-Rich Milk Fat Diet Provides Protection against Gastrointestinal Leakiness in Mice Treated with Lipopolysaccharide. J. Dairy Sci. 2011, 94, 2201–2212.

- Fontecha, J.; Brink, L.; Wu, S.; Pouliot, Y.; Visioli, F.; Jiménez-Flores, R. Sources, Production, and Clinical Treatments of Milk Fat Globule Membrane for Infant Nutrition and Well-Being. Nutrients 2020, 12, 25.

- Durso, L.; Hutkins, R. Starter Cultures. In Encyclopedia of Food Sciences and Nutrition; Caballero, B., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 5583–5593. ISBN 978-0-12-227055-0.

- Zhang, L.; García-Cano, I.; Jiménez-Flores, R. Effect of Milk Phospholipids on the Growth and Cryotolerance of Lactic Acid Bacteria Cultured and Stored in Acid Whey-Based Media. JDS Commun. 2020, S2666910220300351.

- McSweeney, P.L.H.; Sousa, M.J. Biochemical Pathways for the Production of Flavour Compounds in Cheeses during Ripening: A Review. Lait 2000, 80, 293–324.

- Smit, G.; Smit, B.A.; Engels, W.J.M. Flavour Formation by Lactic Acid Bacteria and Biochemical Flavour Profiling of Cheese Products. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2005, 29, 591–610.

- Busscher, H.J. Specific and Non-Specific Interactions in Bacterial Adhesion to Solid Substrata. FEMS Microbio. Rev. 1987, 46, 9.

- An, Y.H.; Friedman, R.J. Concise Review of Mechanisms of Bacterial Adhesion to Biomaterial Surfaces. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1998, 43, 338–348.

- Laloy, E.; Vuillemard, J.-C.; El Soda, M.; Simard, R.E. Influence of the Fat Content of Cheddar Cheese on Retention and Localization of Starters. Int. Dairy J. 1996, 6, 729–740.

- Auty, M.A.E.; Gardiner, G.E.; McBrearty, S.J.; O’Sullivan, E.O.; Mulvihill, D.M.; Collins, J.K.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; Stanton, C.; Ross, R.P. Direct in Situ Viability Assessment of Bacteria in Probiotic Dairy Products Using Viability Staining in Conjunction with Confocal Scanning Laser Microscopy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001, 67, 420–425.

- Lopez, C.; Maillard, M.-B.; Briard-Bion, V.; Camier, B.; Hannon, J.A. Lipolysis during Ripening of Emmental Cheese Considering Organization of Fat and Preferential Localization of Bacteria. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 5855–5867.

- Lopez, C.; Camier, B.; Gassi, J.-Y. Development of the Milk Fat Microstructure during the Manufacture and Ripening of Emmental Cheese Observed by Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy. Int. Dairy J. 2007, 17, 235–247.

- García-Cano, I.; Rocha-Mendoza, D.; Kosmerl, E.; Jiménez-Flores, R. Purification and Characterization of a Phospholipid-Hydrolyzing Phosphoesterase Produced by Pediococcus Acidilactici Isolated from Gouda Cheese. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, S0022030220301818.

- Moe, K.M.; Faye, T.; Abrahamsen, R.K.; Østlie, H.M.; Skeie, S. Growth and Survival of Cheese Ripening Bacteria on Milk Fat Globule Membrane Isolated from Bovine Milk and Its Monosaccharides. Int. Dairy J. 2012, 25, 29–35.

- Martinovic, A.; Moe, K.M.; Romeih, E.; Aideh, B.; Vogensen, F.K.; Østlie, H.; Skeie, S. Growth of Adjunct Lactobacillus Casei in Cheddar Cheese Differing in Milk Fat Globule Membrane Components. Int. Dairy J. 2013, 31, 70–82.

- Jiménez-Flores, R.; Brisson, G. The Milk Fat Globule Membrane as an Ingredient: Why, How, When? Dairy Sci. Technol. 2008, 88, 5–18.

- Ly, M.H.; Vo, N.H.; Le, T.M.; Belin, J.-M.; Waché, Y. Diversity of the Surface Properties of Lactococci and Consequences on Adhesion to Food Components. Colloids Surf. B 2006, 52, 149–153.

- Brisson, G.; Payken, H.F.; Sharpe, J.P.; Jiménez-Flores, R. Characterization of Lactobacillus Reuteri Interaction with Milk Fat Globule Membrane Components in Dairy Products. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 5612–5619.

- Guerin, J.; Soligot, C.; Burgain, J.; Huguet, M.; Francius, G.; El-Kirat-Chatel, S.; Gomand, F.; Lebeer, S.; Le Roux, Y.; Borges, F.; et al. Adhesive Interactions between Milk Fat Globule Membrane and Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG Inhibit Bacterial Attachment to Caco-2 TC7 Intestinal Cell. Colloids Surf. B 2018, 167, 44–53.

- Kamińska, A.; Enguita, F.J.; Stępień, E.Ł. Lactadherin: An Unappreciated Haemostasis Regulator and Potential Therapeutic Agent. Vascul. Pharmacol. 2018, 101, 21–28.

- Patton, S.; Gendler, S.J.; Spicer, A.P. The Epithelial Mucin, MUC1, of Milk, Mammary Gland and Other Tissues. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1995, 1241, 407–423.

- Recio, I.; Moreno, F.J.; López-Fandiño, R. Glycosylated dairy components: Their roles in nature and ways to make use of their biofunctionality in dairy products. In Dairy-Derived Ingredients; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 170–211. ISBN 978-1-84569-465-4.

- Gupta, V.K.; Tuohy, M.G.; O’Donovan, A.; Lohani, M. (Eds.) Biotechnology of Bioactive Compounds: Sources and Applications; Wiley-Blackwell: Chichester, UK; Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; ISBN 978-1-118-73344-8.

- Verma, A.; Ghosh, T.; Bhushan, B.; Packirisamy, G.; Navani, N.K.; Sarangi, P.P.; Ambatipudi, K. Characterization of Difference in Structure and Function of Fresh and Mastitic Bovine Milk Fat Globules. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221830.

- Shahriar, F.; Ngeleka, M.; Gordon, J.R.; Simko, E. Identification by Mass Spectroscopy of F4ac-Fimbrial-Binding Proteins in Porcine Milk and Characterization of Lactadherin as an Inhibitor of F4ac-Positive Escherichia Coli Attachment to Intestinal Villi in Vitro. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 2006, 30, 723–734.

- Zhang, L.; García-Cano, I.; Jiménez-Flores, R. Characterization of Adhesion between Limosilactobacillus Reuteri and Milk Phospholipids by Density Gradient and Gene Expression. JDS Commun. 2020, S2666910220300326.

- Miyoshi, Y.; Okada, S.; Uchimura, T.; Satoh, E. A Mucus Adhesion Promoting Protein, MapA, Mediates the Adhesion of Lactobacillus Reuteri to Caco-2 Human Intestinal Epithelial Cells. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2006, 70, 1622–1628.

- Hsueh, H.-Y.; Yueh, P.-Y.; Yu, B.; Zhao, X.; Liu, J.-R. Expression of Lactobacillus Reuteri Pg4 Collagen-Binding Protein Gene in Lactobacillus Casei ATCC 393 Increases Its Adhesion Ability to Caco-2 Cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 12182–12191.

- Jensen, H.; Roos, S.; Jonsson, H.; Rud, I.; Grimmer, S.; van Pijkeren, J.-P.; Britton, R.A.; Axelsson, L. Role of Lactobacillus Reuteri Cell and Mucus-Binding Protein A (CmbA) in Adhesion to Intestinal Epithelial Cells and Mucus in Vitro. Microbiology 2014, 160, 671–681.

- Rocha-Mendoza, D.; Kosmerl, E.; Miyagusuku-Cruzado, G.; Giusti, M.M.; Jiménez-Flores, R.; García-Cano, I. Growth of Lactic Acid Bacteria in Milk Phospholipids Enhances Their Adhesion to Caco-2 Cells. J. Dairy Sci. 2020, S0022030220305385.

- Zhang, L.; Chichlowski, M.; Gross, G.; Holle, M.; lbarra-Sánchez, L.A.; Wang, S.; Miller, M.J. Milk Fat Globule Membrane Protects Lactobacillus Rhamnosus GG from Bile Stress by Regulating Exopolysaccharide Production and Biofilm Formation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020.

- Ortega-Anaya, J.; Marciniak, A.; Jimenez-Flores, R. Milk Fat Globule Membrane Phospholipids Modify Adhesion of Lactobacillus to Mucus-Producing Caco-2/Goblet Cells by Altering the Cell Envelope. Manuscript in Preparation.

- Quinn, E.M.; Slattery, H.; Thompson, A.P.; Kilcoyne, M.; Joshi, L.; Hickey, R.M. Mining Milk for Factors Which Increase the Adherence of Bifidobacterium Longum Subsp. Infantis to Intestinal Cells. Foods 2018, 7, 196.

- Morifuji, M.; Kitade, M.; Oba, C.; Fukasawa, T.; Kawahata, K.; Yamaji, T.; Manabe, Y.; Sugawara, T. Milk Fermented by Lactic Acid Bacteria Enhances the Absorption of Dietary Sphingomyelin in Rats. Lipids 2017, 52, 423–431.

- Li, X.; Peng, Y.; Li, Z.; Christensen, B.; Heckmann, A.B.; Stenlund, H.; Lönnerdal, B.; Hernell, O. Feeding Infants Formula With Probiotics or Milk Fat Globule Membrane: A Double-Blind, Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Pediatr. 2019, 7, 347.

- Benyacoub, J.; Blum-Sperisen, S.; Bosco, M.N.; Bovetto, L.; Jean, R.; Bureau-Franz, I.; Donnet-Hughes, A.; Schiffrin, E.; Favre, L. Infant Formula with Probiotics and Milk Fat Globule Membrane Components. U.S. Patent WO2011069987A1, 16 June 2011.

- Nieto-Ruiz, A.; García-Santos, J.A.; Bermúdez, M.G.; Herrmann, F.; Diéguez, E.; Sepúlveda-Valbuena, N.; García, S.; Miranda, M.T.; De-Castellar, R.; Rodríguez-Palmero, M.; et al. Cortical Visual Evoked Potentials and Growth in Infants Fed with Bioactive Compounds-Enriched Infant Formula: Results from COGNIS Randomized Clinical Trial. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2456.

- Nieto-Ruiz, A.; Diéguez, E.; Sepúlveda-Valbuena, N.; Catena, E.; Jiménez, J.; Rodríguez-Palmero, M.; Catena, A.; Miranda, M.T.; García-Santos, J.A.G.; Bermúdez, M.; et al. Influence of a Functional Nutrients-Enriched Infant Formula on Language Development in Healthy Children at Four Years Old. Nutrients 2020, 12, 535.