Climate change affects the possibility of crop production and yield and disrupting the maintenance of crop biodiversity, including ornamentals. Warsaw is located in a temperate zone with mixed continental and oceanic climate influences. This research examines the response of once-blooming rambler roses to changing climate conditions in connection with their frost resistance and ornamental value. The 15 selected rambler rose cultivars were observed in the years 2000–2016 in the Polish Academy of Sciences Botanical Garden—Center for Biological Diversity Conservation in Powsin. Damage to shrubs caused by frost, the timing of bud break, leaf development, and initial, full, and final flowering were recorded. The changes in phenology and frost damage were the effect of weather conditions in the autumn–winter–spring period. Frost damage influenced the flowering and growth of plants in different ways, depending on the extent of required pruning. Their reintroduction helped to maintain biodiversity of old cultivars, which makes these roses a proposal for the lowlands of Central Europe.

- climate change

- frost damage

- growing season

- historical roses

- phenology

- precipitation

- temperature

- urban greening

- winter hardiness

1. Introduction

Knowledge of the phenology of wild and cultivated plants is important for horticultural crop production, meteorological sciences, and botany [1][2]. Plant phenology is a source of knowledge of periodic biological events affected by the environment and also the most reliable bioindicator [3][4]. It reflects biological and physical systems independently [5]. Changes in springtime phenological events of perennial [6][7][8] and woody plants have often been documented [3][5][7][9] and are more consistent in direction and magnitude than changes in summer and autumn phenophases [4][5][7][9][10]. Zheng et al. [5] selected 11 phenophases in nine woody species, namely, bud expansion, bud burst, first flowering, 50% of full flowering, end of flowering, first leaf, 50% of full leaf expansion, beginning of leaf coloring, end of leaf coloring, beginning of leaf fall, and end of leaf fall [5]. The beginning dates of spring and summer phenophases advanced with time, while the start of autumn and winter phenophases became delayed. These changes were significantly correlated with temperature [5]. Changes in climate can affect bud dormancy and cold hardiness, which are critical adaptations for the survival of winter cold stress by perennial plants of the temperate zone, Vitis species among them [11]. Bud dormancy allows perennial and woody plants to survive the winter in temperate climates [12].

To examine the effects of climate change, botanical gardens make standard phenological observations of many plant taxa growing on their area limiting the number of factors that might alter long term changes [13]. Their behavior can provide insight into how species will respond in the wild in terms of, e.g., changes in flowering, leaf-out times, and fruiting [13]. The same principles can be applied to crops and ornamental plants. Botanical gardens located in large urban areas have tended to warm more rapidly than surrounding areas because of the urban heat island effect [13]. Moreover, the effects of gas pollution on many plant traits, such as their phenology, seem minor in relation to the effects of temperature, light, and precipitation [14]. Botanical gardens have a unique set of resources, including controlled growing conditions, which allows them to host important climate change research that cannot be easily undertaken elsewhere. Due to hosting large collections of plants from a wide range of areas, they are in the position to address many questions related to climate change that are often too difficult to examine at any other location [15]. Observations in botanical gardens are recorded annually or periodically by experienced staff, and these records can also be used to track changes in anatomy or physiology [13].

The rapid climatic changes observed over several dozens of years indicate that the average temperature has risen and the vegetation season has been slightly prolonged in the European area [16]. These changes influence the diversity and distribution of species, and consequently ecosystems and biodiversity. It is estimated that ca. 32% of European plant species present in 1990 will disappear by 2050. These species take up 44% of the modeled European area. The distribution of natural species is projected to shift towards the north-east [16]. Due to climatic change, some species will no longer be able to grow at their present locations due to lack of temperature tolerance, water stress, competition with other plant species, or changes in patterns of herbivory [16][17][18].

The import of new species to nurseries and, in consequence, to the market poses a risk of their emergence as invasive species in the local environment and landscape, particularly in rural areas [19]. The most decisive climate factors limiting the number of non-native plant species able to grow are not only frost resistance and autumn–winter–spring conditions but also the ability to grow in a changing climate [19][20]. During the years 2002–2016 1781 new species and cultivars were introduced in Polish nurseries associated with the Polish Nurserymen Association [21]. Most of them come from a higher zone—6B in the USDA codification [22]—and originate from, e.g., Western Europe or Asia [19]. However, agriculture, horticulture, and forestry are the main sources of alien plant expansion. Such species can become invasive and lead to the extinction and reduction of native species [23].

The use of cultivars in gardens limited the introduction of new potentially invasive species to the market by what is safer for maintaining the biodiversity of the environment; however, some are expansive, and their seed production should be evaluated in this regard. Their invasiveness needs to be considered on the basis of the evaluation of the entire life cycle of the cultivar and its offspring [24].

Roses are one of the oldest cultivated crops [25] and most important ornamental plants [26][27]; moreover, they have been significant in many fields of human life, both in Asia and in Europe, for thousands of years. The cultivated species, varieties, and cultivars of roses are arranged in several dozen groups in terms of origin and type of growth [25]. Roses can be ordered in terms of type of growth into the following groups: Hybrid Teas, Floribundas, Polyanthas, Miniatures, Rambler and Climbers, Shrubs, and Ground Cover [25][28]. The classification of basic groups of historical rambler roses in terms of their origin includes, e.g., Hybrid Wichurana, Hybrid Setigera, and Hybrid Multiflora [25][28]. The healing properties of roses have been appreciated and documented for centuries. The production of petal oil, the most important rose ingredient used in perfumery and the cosmetic industry, is estimated to continue expansion [3]. Rose oil also has applications in pharmacology, in which it is used for its anti-HIV, antibacterial, antioxidant, hypnotic, antidiabetic, and relaxant effects [27]. Climbing roses are a very diverse group of varied origin and different decorative values [21][25][28]. They are traditionally used in parks, courtyards, squares, estate greenery, and gardens. They do not require much space and are able to vine up walls in very narrow streets, right next to buildings and small courtyards [21][28] like other climbing plants [29]. Roses planted in restaurant and café gardens make sitting at nearby tables more pleasant. The importance of roses as part of the greenery in the city is not to be questioned [21][28]. Moreover, most rose cultivars produce few or no seeds and are not expansive [21][25][28].

2. Flowering

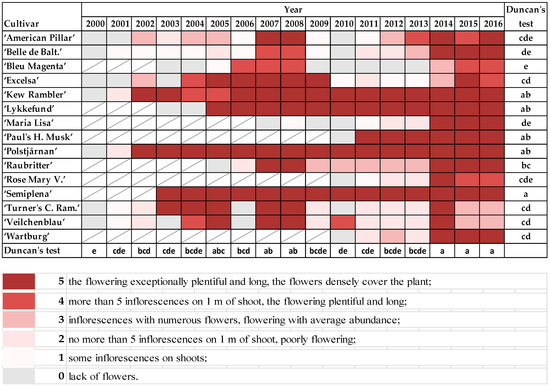

The rambler roses started flowering in the first days of June. “Maria Lisa”, “Paul’s Himalayan Musk”, and “Polstjårnan” were the first to start blooming; “Excelsa” and “Rose Mary Viaud” were the last (Figure S4). If the shoots were damaged to the ground (points 6 and 7 on the scale), the low pruned shrubs did not flower, or only a few flowers appeared on old parts of shoots. Exceptionally plentiful and long flowering was observed in “Semiplena” and “Kew Rambler”, “Lykkefund”, “Paul’s Himalayan Musk”, and “Polstjårnan”. Low quality of flowering, especially after frosty winters, were noticed in “Bleu Magenta”, “American Pillar”, “Belle de Baltimore”, “Maria Lisa”, and “Rose Mary Viaud”. Moreover, the flowering was exceptionally plentiful after mild winters (2007, 2008, and 2014−2016) in all plants that were already a few years old (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The abundance of flowering in rambler roses on the following scale: 0—lack of flowers; 1—some inflorescences on shoots; 2—no more than 5 inflorescences on 1 m of shoot, but flowering poorly; 3—inflorescences with numerous flowers, but flowering with average abundance; 4—more than 5 inflorescences on 1 m of shoot, plentiful and long flowering; 5—exceptionally plentiful and long flowering, the flowers densely cover the plant. Different letters indicate significant differences in the cultivars and the years. The Duncan’s test (α = 0.05) was used.

Correlation analysis of the ramblers for the timing of the start of flowering showed a strict relationship between the average temperature in winter and spring months for all cultivars. A decrease in the average temperature in March correlated with a later start to flowering in “American Pillar”, “Belle de Baltimore”, “Excelsa”, “Polstjårnan”, and “Raubritter”, while a decrease in the average temperature in April was connected with a later start to the flowering of “Kew Rambler” and “Veilchenblau” (Table 2).

Table 2. The part of matrices of effect correlations between average monthly air temperature (2006, 2010, and 2016) and the start of the flowering period (BBCH 60 601) in rambler roses.

| Cultivar | SD | Month | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| October | November | December | January | February | March | April | ||

| “American Pillar” | 9.87 | 0.971 *** | −0.745 ** | 0.974 *** | 0.574 * | 0.414 | −0.988 *** | 0.868 *** |

| “Belle de Baltimore” | 7.64 | 0.779 ** | −0.957 *** | 0.978 *** | 0.176 | −0.008 | −0.960 *** | 0.996 *** |

| “Bleu Magenta” | 9.81 | 0.763 ** | 0.104 | 0.388 | 0.998 *** | 0.981 *** | −0.455 | 0.106 |

| “Excelsa” | 11.55 | 0.179 | −0.914 *** | 0.604 * | −0.512 * | −0.661 * | −0.543 * | 0.808 ** |

| “Kew Rambler” | 2.52 | −0.555 * | 0.998 *** | −0.871 *** | 0.128 | 0.308 | 0.832 ** | −0.976 *** |

| “Lykkefund” | 5.51 | −0.701 ** | −0.194 | −0.303 | −0.997 *** | −0.995 *** | 0.373 | −0.015 |

| “Maria Lisa” | 0.58 | 0.763 ** | 0.104 | 0.388 | 0.998 *** | 0.981 *** | −0.455 | 0.106 |

| “Paul’s Him. Musk” | 4.04 | 0.763 ** | 0.104 | 0.388 | 0.998 *** | 0.981 *** | −0.455 | 0.106 |

| “Polstjårnan” | 7.55 | 0.555 * | −0.998 *** | 0.871 ** | −0.128 | −0.308 | −0.832 ** | 0.976 *** |

| “Raubritter” | 6.51 | 0.612 * | −0.998 *** | 0.903 *** | −0.058 | −0.240 | −0.869 ** | 0.989 *** |

| “Rose Mary Viaud” | 8.66 | 0.763 ** | 0.104 | 0.388 | 0.998 *** | 0.981 *** | −0.455 | 0.106 |

| “Semiplena” | 0.58 | −0.763 ** | −0.104 | −0.388 | −0.998 *** | −0.981 *** | 0.455 | −0.106 |

| “Turner’s Crim. Ram.” | 5.77 | 0.763 ** | 0.104 | 0.388 | 0.998 *** | 0.981 *** | −0.455 | 0.106 |

| “Veilchenblau” | 2.52 | −0.730 ** | 0.976 *** | −0.960 *** | −0.101 | 0.083 | 0.937 *** | −0.998 *** |

| “Wartburg” | 0.58 | 0.763 ** | 0.104 | 0.388 | 0.998 *** | 0.981 *** | −0.455 | 0.106 |

Marked correlations are significant at p < 0.05. Correlation significance: * 0.500–0.699—restrained; ** 0.700–0.899—high; *** >0.900—very high.

3. Conclusions

Ramblers can be cultivated and grow tall in the warmer western parts of Europe, where, because of mild winters, they flower reliably every year [25]. The results confirm that changes in thermal characteristics of the climate of Poland and the associated extension of the meteorological growing season [30][31] and growth season [31] have enabled the introduction of thermophilic plants with higher thermal requirements in cultivation [19][30][31]. Many-year observations of ramblers showed their favorable adaptation to the climate in Poland and the possibility of their wider use in regions with a hitherto cooler climate. However, they have also shown a differentiation in the tolerance of different varieties not only due to frost in winter but also changes in temperature in spring and autumn. These factors had an important influence on the scale of frost damage, growth, and flowering of roses. The average air temperature in autumn-winter-spring correlated strictly with the roses’ early phenological phases.

Rambler roses are a valuable supplement to the available assortment of vines, especially for city greening. Recent years of mild winters and low maintenance made the studied ramblers more useful for a wide range of applications as ornamental plants in parks and rendered them especially preferable for historical garden layout cultivation. This is particularly significant in Central and Eastern Europe, including Poland, where many historical gardens are in poor condition [32].

Currently, rambler roses are not the subject of wide cultivation research, but due to their ornamental merits, which were appreciated in the past, it is worth considering the possibilities for re-establishing their significance. The maintenance of old cultivars, including roses, in cultivation is dependent mostly on resistance to climate conditions.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/plants10030457

References

- Meier, U.; Bleiholder, H.; Brumme, H.; Bruns, E.; Mehring, B.; Proll, T.; Wiegand, J. Phenological growth stages of roses (Rosa sp.): Codification and description according tot he BBCH scale. Ann App Biol. 2009, 154, 231–238.

- Bleiholder, H.; Weber, E.; Feller, C.; Hess, M.; Wicke, H.; Meier, U.; Boom, T.; Lancashire, B.D.; Buhr, L.; Hack, H.; et al. Growth Stages of Mono-and Dicotyledonous Plants; BBCH Monographs; Meier, U., Ed.; Federal Biological Research Centre for Agriculture and Forestry: Berlin and Braunschweig, Germany, 2001; p. 158.

- Ziter, C.D.; Pedersen, E.J.; Kucharik, C.J.; Turner, M.G. Scale-dependent interactions between tree canopy cover and impervious surfaces reduce daytime urban heat during summer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019.

- Gordo, O.; Sanz, J.J. Impact of climate change on plant phenology in Mediterranean ecosystems. Global Change Biol. 2010, 16, 1082–1106.

- Zheng, F.; Tao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Dai, J.; Ge, Q. Variation of main phenophases in phenological calendar in East China and their response to climate change. Adv Meteorol. 2016.

- Badeck, F.W.; Bondeau, A.; Böttcher, K.; Doktor, D.; Lucht, W.; Schaber, J.; Sitch, S. Responses of spring phenology to climate change. New Phytol. 2004, 162, 295–309.

- Bertin, R.I. Plant phenology and distribution in relation to recent climate change. J. Torrey Bot Soc. 2008, 135, 126–146.

- Wolf, A.A.; Zavaleta, E.S.; Selmants, P.C. Flowering phenology shifts in response to biodiversity loss. PNAS 2017, 114, 3463–3468.

- Pihlajaniemi, H.; Siuruainen, M.; Rautio, P.; Laine, K.; Peteri, S.-L.; Huttunen, S. Field evaluation of phenology and success of hardy, micro-propagated old shrub roses in northern Finland. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B-Soil Plant Sci. 2005, 1–12.

- Walther, G.R.; Post, E.; Convey, P.; Menzel, A.; Parmesan, C.; Beebee, T.J.C.; Fromentin, J.M.; Hoegh-Guldberg, O.; Bairlein, F. Ecological responses to recent climate change. Nature 2002, 416, 389–395.

- Kovaleski, A.P.; Reisch, B.I.; Londo, J.P. Deacclimation kinetics as quantitative phenotype for delineating the dormancy transition and thermal efficiency for budbreak in Vitis species. AOB Plants. 2018, 10, ply066.

- Lang, G.A.; Early, J.D.; Martin, A.J.; Darnell, R. Endodormancy, paradormancy, and ecodormancy—Physiological terminology and classification for dormancy research. Hortscience 1987, 22, 371–377.

- Primack, R.B. The role of botanical gardens in climate change research. New Phytol. 2009, 182, 303–313.

- Cleland, E.E.; Chiariello, N.R.; Loarie, S.R.; Mooney, H.A.; Field, C.B. Diverse responses of phenology to global changes in a grassland ecosystem. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 13740–13744.

- Bakkenes, M.; Alkemade, J.R.M.; Ihle, F.; Leemans, R.; Latour, J.B. Assessing effects of forecasted climate change on the diversity and distribution of European higher plants for 2050. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2002, 8, 390–407.

- Ibanez, I.; Clark, J.S.; Dietze, M.C.; Feeley, K.; Hersh, M.; LaDeau, S.; McBride, A.; Welch, N.E.; Wolosin, M.S. Predicting biodiversity change: Outside the climate envelope, beyond the species-area curve. Ecology 2006, 87, 1896–1906.

- Morin, X.; Augspurger, C.; Chuine, I. Process-based modeling of species’ distributions: What limits temperate tree species’ range boundaries? Ecology 2007, 88, 2280–2291.

- Yu, Q.; Ja, D.R.; Tian, B.; Yang, Y.P.; Duan, Y.W. Changes of flowering phenology and flower size in rosaceous plants from a biodiversity hotspot in the past century. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 28302.

- Marosz, A. Introducing new species and cultivars according to climate, demographic and economic changes in Poland–horticultural view. Infrastruct. Ecol. Rural Areas. 2015, 3, 797–807.

- Vitasse, Y.; François, C.; Delpierre, N.; Dufrêne, E.; Kremer, A.; Chuine, I.; Delzon, S. Assessing the effects of climate change on the phenology of European temperate trees. Agric. Forest Meteorol. 2010, 151, 969–980.

- Marczyński, S. Clematis i inne Pnącza Ogrodowe; MULTICO Oficyna Wydawnicza: Warsaw, Poland, 2011; p. 280.

- Plant Map. Poland Plant Hardiness Zone Map. Available online: (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- Tokarska-Guzik, B.; Dajdok, Z.; Zając, M.; Zając, A.; Urbisz, A.; Danielewicz, W.; Hołdyński, C. Rośliny Obcego Pochodzenia w Polsce ze Szczególnym Uwzględnieniem Gatunków Inwazyjnych; Generalna Dyrekcja Ochrony Środowiska: Warsaw, Poland, 2012; p. 106.

- Knight, T.M.; Havens, K.; Vitt, P. Will the use of less fecund cultivars reduce the invasiveness of perennial plants? BioScience 2011, 61, 816–822.

- Gustavsson, L. Rosen Leksikon; Rosinante: Copenhagen, Denmark, 1999; p. 544.

- Smulders, M.J.M.; Arens, P.; Bourke, P.M.; Debener, T.; Linde, M.; Riek, J.; Leus, L.; Ruttink, T.; Baudino, S.; Saint-Oyant, L.H.; et al. In the name of the rose: A roadmap for rose research in the genome era. Hortic. Res. 2019, 6, 65.

- Market Research Report. Rose Oil Market Size, Share and Trends Analysis Report by Application (Fragrance and Cosmetics, Pharmaceuticals, Food and Beverages), by Product (Organic, Conventional), and Segment Forecasts, 2019–2025. Report ID:GVR-3-68038-655-4. 2019. Available online: (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- Monder, M.J. Róże do Warunków Klimatycznych Polski; Plantpress: Kraków, Poland, 2018; p. 308.

- Borowski, J. Impact of climbing plants on buildings and their environment. In Design Solutions for nZEB Retrofit Buildings; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2018; pp. 297–309.

- Krużel, J.; Ziernicka-Wojtaszek, A.; Borek, Ł.; Ostrowski, K. Zmiany czasu trwania meteorologicznego okresu wegetacyjnego w Polsce w latach 1971–2000 oraz 1981–2010. Ecol. Eng. 2015, 44, 47–52.

- Żmudzka, E. Wieloletnie zmiany zasobów termicznych w okresie wegetacyjnym i aktywnego wzrostu roślin w Polsce. Woda-Środowisko-Obszary Wiej. 2012, 12, 377–389.

- Kubus, M. Stan zachowania wybranych założeń rezydencjonalno-ogrodowych w województwie zachodniopomorskim. In Założenia Rezydencjonalno-Ogrodowe Dziedzictwa Narodu Polskiego na tle Europejskich Wpływów Kulturowych; Mitkowska, A., Mirek, Z., Hodor, K., Eds.; Instytut Botaniki im. W. Szafera PAN: Kraków, Poland, 2008; pp. 121–127.