Overexploitation of resources makes the reutilization of waste a focal topic of modern society, and the question of the kind of wastes that can be used is continuously raised. Sewage sludge (SS) is derived from the wastewater treatment plants, considered important underused biomass, and can be used as a biofertilizer when properly stabilized due to the high content of inorganic matter, nitrate, and phosphorus. However, a wide range of pollutants can be present in these biosolids, limiting or prohibiting their use as biofertilizer, depending on the type and origin of industrial waste and household products. Long-term applications of these biosolids could substantially increase the concentration of contaminants, causing detrimental effects on the environment and induce hyperaccumulation or phytotoxicity in the produced crops.

- by-products

- biosolids

- organic compounds

- circular economy

- total lifecycle assessment

- biomass effect

1. Introduction

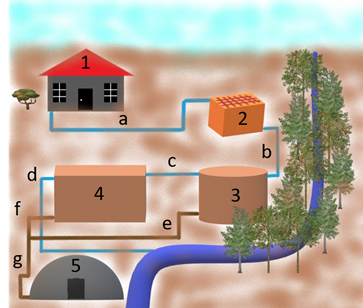

Figure 1. Wastewater treatment facility diagram (adapted from Demirbas et al. [5]). 1—treatment facility, 2—preliminary treatment, 3—primary treatment, 4—secondary treatment, 5—sludge dehydration, a—wastewater, b—sifted wastewater, c—wastewater without sediment, d—treated wastewater for stream discharge, e—primary sludge, f—secondary sludge, g—mixed sludges.

2. Sewage Sludge and Biosolids Analysis

Sewage sludge and biosolids could be considered a double-edged sword. On one hand, it represents a potential source of nutrients for plant growth and a material that can be used to improve the physical properties of the soil. However, on the other hand, it may also contain a range of potentially toxic metals, which could be dangerous for human health, primarily through the consumption of plants grown in sludge-enriched soils. Industrial effluents are a significant source of heavy metals in SS and biosolids because the concentration of some of those elements is usually extremely high in industrial sludges. Most organic contaminants and pharmaceutical products in SS are concentrated after wastewater treatments, by particle precipitation. There is a wide variation of heavy metals limit values, even between similar geographical areas, type of amendment, and applied concentration of biosolids. The pH values, the amounts of NPK nutrients, heavy metals in SS from several studies, and different locations are presented in Table 2. These values were compared and discussed according to the Council Directive No. 86/278/EEC [3] due to the limiting regulations that control the contaminants in SS for agriculture purposes. The outliers were underlined and marked in bold.

| pH | N | P | K | Cd | Cr | Cu | Hg | Ni | Pb | Zn | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country/City | g kg−1 DW | mg kg−1 DW | ||||||||||

| Argentina/Buenos Aires | - | 2.7 ± 0.47 | 7.7 ± 1.4 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 3.9 ± 1.9 | 155.6 ± 51.8 | 360.3 ± 80.9 | - | 85.5 ± 76.1 | 322.7± 151.6 | 1526 ± 523 | [40] |

| Australia/Brisbane | - | - | - | - | 1.8 | 16.7 ± 0.3 | 447.7 ± 1.5 | - | 19.8 ± 0.2 | 41.7 ± 0.3 | 830.6 ± 4.2 | [41] |

| Brazil/Jaboticabal | - | 34.08 | 21.62 | 1.9 | 11 | 808 | 722 | - | 231 | 186 | 2159 | [42] |

| China/Hebei | 5.8 | 56.6 | 9.8 | - | 0.3 | 83.51 | 221.9 | - | 32.62 | 73.31 | [22] | |

| China/Taiyuan | - | - | - | - | 22.1 | 245.8 | 1122 | 20.6 * | - | 118.5 | 3059 | [43] |

| Denmark/Copenhagen | 7.7 | 47 | 33 | - | 1.4 | 98 | 244 | - | 31 | 178 | 1041 | [44] |

| Finland/Helsinki | 7.2 | 0.031 | 0.026 | 0.002 | 0.4 | 30 | 270 | - | 20 | 20 | 470 | [39] |

| India/New Delhi | 6.4 | 18 | 16.1 | 1.83 | - | - | 173 | - | - | 78 | 1853 | [45] |

| India/Uttarakhand | 9.0 | - | 0.216 ± 0.002# | - | 10.24 ± 0.14 | 8.63 ± 1.06 | 18.96 ± 1.09 | - | - | 9.33 ± 1.01 | 11.25 ± 1.00 | [46] |

| India/Varanasi | 7.0 | 17.3 ± 0.2 | 0.717 ± 0.06 | 0.209 ± 0.002 | 154.5 ± 2.52 | 35.5 ± 0.76 | 317.7 ± 1.92 | - | 18.9 ± 0.09 | 60 ± 5.77 | 785.3 ± 16.69 | [38] |

| Morocco/Meknès-Saïs | 6.1 | 52.2 ± 2 | 0.586 ± 0.018 # | 0.920 ± 0.021 | 1.15 ± 0.2 | 32.8 ± 2.4 | 17.9 ± 1.2 | 0.44 ± 0.1 | 20.9 ± 1.7 | 81 ± 4.5 | 215 ± 12.4 | [6] |

| Pakistan/Multan | 6.9 | 14.6 | 13.38 | - | 5.5 | - | 145 | - | 35 | 20 | - | [47] |

| Pakistan/Multan | 7.6 | 6 | 13 | 13 | 26 | - | - | - | 160 | 13 | - | [48] |

| Spain/Alicante | 6.5 | 2.48 | 5.62 | 7.89 | 1.6 | 16.6 | 157 | n.d. | n.d. | 40.8 | 470 | [20] |

Underlined and in bold are the values that exceed the maximum allowable concentrations for heavy metals according to the Council Directive 86/278/EEC of June 12, 1986 [3]. n.d.—not determined. *—ppb (parts per billion). #—Extractable phosphorus—Olsen Method. Ref.—References.

3. Soil Analyses

The agricultural use of SS and biosolids is a worldwide effective sludge disposal technique. However, its application in agricultural soils must be well thought out, regarding human food consumption. Soil amendments with these resources have been reportedly useful in increasing the number of agro-morphological attributes and yields in different crop species [49], but it is common knowledge that this kind of biomass often contains heavy metals and toxic organic residues. Its indiscriminate use can be detrimental to soil productivity and cause harm to the food chain [37]. Further, dietary intake of heavy metal-contaminated plant food can affect human health in the long term by damaging the nervous, pulmonary, and renal systems [50]. There is a wide variation in limit values for heavy metals, even between similar geographical areas, and depends on the food crops species and the kind of amendment and applied ratios. The extent of heavy metal uptake by plants grown in soil amended with sludge/compost has been evaluated in different locations, as indicated in Table 2. The Codex Alimentarius Commission developed in a joint FAO and WHO [51] effort together with the European Union Commission Regulation No. 1881/2006 of December 19, 2006 [52] which regulates the maximum levels of contaminants in foods. Unfortunately, these could not be compared with the values in Table 2, due to the discrepancy between fresh and dry weight values present in the current legislation and revised works, respectively, without the water content information.

Table 2. Soil analysis.

| pH | EC | Organic Matter | N | P | K | Cd | Cr | Cu | Hg | Ni | Pb | Zn | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country/City | dS m−1 | g kg−1 DW | mg kg−1 DW | |||||||||||

| China/Taiyuan | 7.2 | - | - | 1.2 | - | - | 38 | 112.5 | 34.6 | - | - | 87.7 | 81.2 | [43] |

| Egypt/Sohag | 7.9 | 0.61 | 2 | 0.053 | 0.003 | 0.077 | 0.5 | - | 11 | - | - | 7 | 32 | [53] |

| India/New Delhi | 8.4 | 0.19 | - | 0.0116 | 2.65 | 141.5 | - | - | 2.07 | - | - | 0.056 | 3.76 | [45] |

| India/Uttarakhand | 7.4 | 2.63 | - | - | - | - | 0.09 | 0.18 | 2.42 | - | - | 0.12 | 0.88 | [46] |

| India/Varanasi | 8.2 | 0.24 | - | 1.8 | 0.054 | - | 1.51 | 0.34 | 3.51 | - | 4.95 | 2.83 | 2.11 | [38] |

| Morocco/Meknès-Saïs | 8.2 | 0.1 | 9.8 | 0.7 | - | 0.271 | 0.22 | 57.5 | 1.6 | <0.1 | 21.5 | 16.2 | 3.1 | [6] |

| Poland/Silesia | 7.9 | - | - | 0.481 | 0.015 | - | 2.3 | 26.32 | 29.44 | - | 28.99 | 46.57 | 112 | [31] |

| Spain/Alicante | 7.9 | 1.64 | 1.29 | 0.0125 | 0.007 | 0.3 | 0.15 | 14.7 | 0.94 | n.d. | n.d. | 0.21 | 0.59 | [20] |

| Spain/Murcia | 8.5 | 0.16 | 6.71 | 0.66 | 0.32 | 4.76 | 0.1 | - | 7.3 | - | 14.3 | - | 24.3 | [54] |

| Spain/Santiago de Compostela | 4.8 | - | - | 5 | - | - | - | 30 | 12 | - | 20 | 36 | 78 | [55] |

| Tunisia/Tunes | 8.0 | 0.263 | - | 1.1 | - | - | - | - | 32 | - | 50 | 22 | 70 | [56] |

| U.K./Reading | 5.6 | - | 77 | - | 1.208 | - | 1.2 | 35 | 38 | 0.2 | 12 | 34 | 71 | [57] |

Underlined and in bold are the values that exceed the maximum allowable concentrations for heavy metals according to the Council Directive 86/278/EEC of June 12, 1986 [3], or/and for FAO—wastewater treatment and use in agriculture [16], or/and WHO human health-related chemical guidelines for reclaimed waster and SS applications in agriculture [39]. n.d.—not determined. Ref.—References.

4. Food Crops

| Specie/Plant Organ * | Cd | Cr | Cu | Ni | Pb | Zn | Sewage Sludge/Compost Application | City/Country | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g kg−1 DW | |||||||||

| Hordeum vulgare/Seeds | - | - | 5.4 ± 0.5 | 0.060 ± 0.010 | - | 20 ± 3 | 22.3 ton ha−1 year−1 | Girona/Spain | [1] |

| Hordeum vulgare/Seeds | - | - | 2.8 | - | - | 15.3 | 150 ton ha−1 compost (2:1, wood waste:SS) | Taiyuan/China | [43] |

| Hordeum vulgare/Seeds | 0.038 | - | 11.2 | 1.29 | - | 61.7 | 80 ton ha−1 | Murcia/Spain | [59] |

| Phaseolus vulgaris/Fruit | 2a | 0.4a | 0.8a | - | 0.02a | 5a | 100% | Haridwar/India | [46] |

| Vigna radiata/Fruit | 1.62 ± 0.13 | 1.47 ± 0.15 | 2.22 ± 0.22 | 5.67 ± 0.51 | 3.47 ± 0.35 | 22.07 ± 1.08 | 120 ton ha−1 | Varanasi/India | [60] |

| Brassica rapa/Leaves | - | - | 21.9 | - | - | 23.8 | 150 ton ha−1 compost (2:1, wood waste:SS) | Taiyuan/China | [43] |

| Lactuca sativa/ Leaves | 1.2 | - | 12.3 | 28 | - | 202 | 80 ton ha−1 | Murcia/Spain | [55] |

| Zea mays/Seeds | - | - | 1.8 ± 0.6 | 280 ± 50 | - | 17.5 ± 0.8 | 25.4 ton ha−1 year−1 | Girona/Spain | [1] |

| Zea mays/Seeds | 0.06 | 10.55 | 5.6 | 0.98 | - | 85.8 | Pots with 2.66 kg of SS on top + 13.33 kg of Soil | Helsinki/Finland | [39] |

| Zea mays/Seeds | - | - | - | 2.65 | - | - | 67.5 ton ha−1 | Jaboticabal/Brazil | [42] |

| Brassica oleracea cv. Blue Vantage/Leaves | 0 | 0.04 | 2 | 0.36 | 0.06 | 7.5 | 2.69 ton ha−1 | Kentucky/USA | [61] |

| Brassica oleracea cv. Packman/heads | 0 | 0.05 | 3 | 0.475 | 0.1 | 18 | 0.67 ton ha−1 | Kentucky/USA | [61] |

| Abelmoschus esculentus/Fruit | 21 | 1.1 | 9.4 | 7.3 | 4.3 | 34.3 | 40% (w/w) | Varanasi/India | [62] |

| Brassica napus/Seeds | 0.05 | 0.12 | 2.5 | 0.22 | - | 19.5 | Pots with 2.66 kg of SS on top + 13.33 kg of Soil | Helsinki/Finland | [39] |

| Oryza sativa/Seeds | 2.28 ± 0.03 | 6.37 ± 0.13 | - | 11.68 ± 0.49 | 0.85 ± 0.08 | 22.59 ± 2.73 | 40 ton ha−1 | Varanasi/India | [63] |

| Beta vulgaris/Leaves | 25a | 3a | 22a | 5a | 2a | 75a | 40% (w/w) | Varanasi/India | [38] |

| Triticum aestivum/Seeds | 1.09 ± 0.02 | 0.49 ± 0.03 | - | 2.32 ± 0.23 | n.d. | 52.44 ± 0.84 | 40 ton ha−1 | Varanasi/India | [63] |

| Triticum vulgare/Seeds | 0.15 ± 0.05 | - | 8.333 ± 0.775 | - | 4.800 ± 0.087 | 16.202 ± 0.368 | 75% (w/w) | Sohag/Egypt | [54] |

7. Phytoremediation and Bioenergetics

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su13042317

References

- Iglesias, M.; Marguí, E.; Camps, F.; Hidalgo, M. Extractability and crop transfer of potentially toxic elements from mediterranean agricultural soils following long-term sewage sludge applications as a fertilizer replacement to barley and maize crops. Waste Manag. 2018, 75, 312–318.

- Wang, Q.; Shaheen, S.M.; Jiang, Y.; Li, R.; Slaný, M.; Abdelrahman, H.; Kwon, E.; Bolan, N.; Rinklebe, J.; Zhang, Z. Fe/Mn- and P-modified drinking water treatment residuals reduced Cu and Pb phytoavailability and uptake in a mining soil. J. Hazard Mater. 2021, 403.

- European Commission. Protection of the Environment, and in particular of the soil, when sewage sludge is used in agriculture. Off. J. Eur. Communities 1986, 4, 6–12.

- Burducea, M.; Zheljazkov, V.D.; Lobiuc, A.; Pintilie, C.A.; Virgolici, M.; Silion, M.; Asandulesa, M.; Burducea, I.; Zamfirache, M.M. Biosolids application improves mineral composition and phenolic profile of basil cultivated on eroded soil. Sci. Hortic. 2019, 249, 407–418.

- Demirbas, A.; Edris, G.; Alalayah, W.M. Sludge production from municipal wastewater treatment in sewage treatment plant. Energy Sources Part. A Recover. Util. Environ. Eff. 2017, 39, 999–1006.

- Mohamed, B.; Mounia, K.; Aziz, A.; Ahmed, H.; Rachid, B.; Lotfi, A. Sewage sludge used as organic manure in Moroccan sunflower culture: Effects on certain soil properties, growth and yield components. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 627, 681–688.

- Yuan, Z.; Pratt, S.; Batstone, D.J. Phosphorus recovery from wastewater through microbial processes. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2012, 23, 878–883.

- Krzyzanowski, F.; de Souza Lauretto, M.; Nardocci, A.C.; Sato, M.I.Z.; Razzolini, M.T.P. Assessing the probability of infection by Salmonella due to sewage sludge use in agriculture under several exposure scenarios for crops and soil ingestion. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 568, 66–74.

- Lloret, E.; Pastor, L.; Pradas, P.; Pascual, J.A. Semi full-scale thermophilic anaerobic digestion (TAnD) for advanced treatment of sewage sludge: Stabilization process and pathogen reduction. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 232, 42–50.

- Dabrowska, L.; Rosińska, A. Change of PCBs and forms of heavy metals in sewage sludge during thermophilic anaerobic digestion. Chemosphere 2012, 88, 168–173.

- Yang, L.; Liu, W.; Zhu, D.; Hou, J.; Ma, T.; Wu, L.; Zhu, Y.; Christie, P. Application of biosolids drives the diversity of antibiotic resistance genes in soil and lettuce at harvest. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 122, 131–140.

- García-Santiago, X.; Franco-Uría, A.; Omil, F.; Lema, J.M. Risk assessment of persistent pharmaceuticals in biosolids: Dealing with uncertainty. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 302, 72–81.

- Shamuyarira, K.K.; Gumbo, J.R. Assessment of heavy metals in municipal sewage sludge: A case study of Limpopo Province, South Africa. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2014, 11, 2569–2579.

- Stevens, J.L.; Northcott, G.L.; Stern, G.A.; Tomy, G.T.; Jones, K.C. PAHs, PCBs, PCNs, organochlorine pesticides, synthetic musks, and polychlorinated n-alkanes in U.K. sewage sludge: Survey results and implications. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 462–467.

- Navarro, I.; de la Torre, A.; Sanz, P.; Fernández, C.; Carbonell, G.; Martínez, M. de los Á. Environmental risk assessment of perfluoroalkyl substances and halogenated flame retardants released from biosolids-amended soils. Chemosphere 2018, 210, 147–155.

- FAO. Agricultural Use of Sewage. In Waste Water Treatment and Use in Agriculture, FAO Irrigation and Drawing Paper 47; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 1992.

- Xu, P.; Liu, A.; Li, F.; Tinkov, A.A.; Liu, L.; Zhou, J.C. Associations between Metabolic Syndrome and Four Heavy Metals: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 273, 116480.

- Veeken, A.H.M.; Hamelers, H.V.M. Removal of heavy metals from sewage sludge by extraction with organic acids. Water Sci. Technol. 1999, 40, 129–136.

- Geng, H.; Xu, Y.; Zheng, L.; Gong, H.; Dai, L.; Dai, X. An overview of removing heavy metals from sewage sludge: Achievements and perspectives. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266, 115375.

- Casado-Vela, J.; Sellés, S.; Díaz-Crespo, C.; Navarro-Pedreño, J.; Mataix-Beneyto, J.; Gómez, I. Effect of composted sewage sludge application to soil on sweet pepper crop (Capsicum annuum var. annuum) grown under two exploitation regimes. Waste Manag. 2007, 27, 1509–1518.

- Suthar, S. Pilot-scale vermireactors for sewage sludge stabilization and metal remediation process: Comparison with small-scale vermireactors. Ecol. Eng. 2010, 36, 703–712.

- Kong, L.; Liu, J.; Han, Q.; Zhou, Q.; He, J. Integrating metabolomics and physiological analysis to investigate the toxicological mechanisms of sewage sludge-derived biochars to wheat. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 185, 109664.

- Samaras, P.; Papadimitriou, C.A.; Haritou, I.; Zouboulis, A.I. Investigation of sewage sludge stabilization potential by the addition of fly ash and lime. J. Hazard. Mater. 2008, 154, 1052–1059.

- Slaný M, Jankovič L, Madejová, J. Structural characterization of organo-montmorillonites prepared from a series of primary alkylamines salts: Mid-IR and near-IR study. Appl. Clay. Sci. 2019, 176, 11–20.

- Martín, J.; Santos, J.L.; Aparicio, I.; Alonso, E. Pharmaceutically active compounds in sludge stabilization treatments: Anaerobic and aerobic digestion, wastewater stabilization ponds and composting. Sci. Total Environ. 2015, 503–504, 97–104.

- Samara, E.; Matsi, T.; Balidakis, A. Soil application of sewage sludge stabilized with steelmaking slag and its effect on soil properties and wheat growth. Waste Manag. 2017, 68, 378–387.

- Wu, L.; Cheng, M.; Li, Z.; Ren, J.; Shen, L.; Wang, S.; Luo, Y.; Christie, P. Major nutrients, heavy metals and PBDEs in soils after long-term sewage sludge application. J. Soils Sediments 2012, 12, 531–541.

- Elmi, A.; Al-Khaldy, A.; AlOlayan, M. Sewage sludge land application: Balancing act between agronomic benefits and environmental concerns. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 250, 119512.

- Guoqing, X.; Xiuqin, C.; Liping, B.; Hongtao, Q.; Haibo, L. Absorption, accumulation and distribution of metals and nutrient elements in poplars planted in land amended with composted sewage sludge: A field trial. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 182, 109360.

- Lag-Brotons, A.; Gómez, I.; Navarro-Pedreño, J.; Mayoral, A.M.; Curt, M.D. Sewage sludge compost use in bioenergy production—A case study on the effects on Cynara cardunculus L energy crop. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 79, 32–40.

- Fijalkowski, K.; Rosikon, K.; Grobelak, A.; Hutchison, D.; Kacprzak, M.J. Modification of properties of energy crops under Polish condition as an effect of sewage sludge application onto degraded soil. J. Environ. Manage. 2018, 217, 509–519.

- Kumar, A.; Kumar, N.; Baredar, P.; Shukla, A. A review on biomass energy resources, potential, conversion and policy in India. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 45, 530–539.

- Pandey, V.C.; Bajpai, O.; Singh, N. Energy crops in sustainable phytoremediation. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 58–73.

- Singh, R.P.; Agrawal, M. Potential benefits and risks of land application of sewage sludge. Waste Manag. 2008, 28, 347–358.

- Smith, S.R. A critical review of the bioavailability and impacts of heavy metals in municipal solid waste composts compared to sewage sludge. Environ. Int. 2009, 35, 142–156.

- Liu, H. Achilles heel of environmental risk from recycling of sludge to soil as amendment: A summary in recent ten years (2007–2016). Waste Manag. 2016, 56, 575–583.

- Sharma, B.; Sarkar, A.; Singh, P.; Singh, R.P. Agricultural utilization of biosolids: A review on potential effects on soil and plant grown. Waste Manag. 2017, 64, 117–132.

- Singh, R.P.; Agrawal, M. Effects of sewage sludge amendment on heavy metal accumulation and consequent responses of Beta vulgaris plants. Chemosphere 2007, 67, 2229–2240.

- Seleiman, M.F.; Santanen, A.; Stoddard, F.L.; Mäkelä, P. Feedstock quality and growth of bioenergy crops fertilized with sewage sludge. Chemosphere 2012, 89, 1211–1217.

- Lavado, R.S. Effects of sewage-sludge application on soils and sunflower yield: Quality and toxic element accumulation. J. Plant. Nutr. 2006, 29, 975–984.

- Farrell, M.; Rangott, G.; Krull, E. Difficulties in using soil-based methods to assess plant availability of potentially toxic elements in biochars and their feedstocks. J. Hazard. Mater. 2013, 250–251, 29–36.

- de Melo, W.J.; de Stéfani Aguiar, P.; Maurício Peruca de Melo, G.; Peruca de Melo, V. Nickel in a tropical soil treated with sewage sludge and cropped with maize in a long-term field study. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2007, 39, 1341–1347.

- Wei, Y.; Liu, Y. Effects of sewage sludge compost application on crops and cropland in a 3-year field study. Chemosphere 2005, 59, 1257–1265.

- Lemming, C.; Oberson, A.; Hund, A.; Jensen, L.S.; Magid, J. Opportunity costs for maize associated with localised application of sewage sludge derived fertilisers, as indicated by early root and phosphorus uptake responses. Plant. Soil 2016, 406, 201–217.

- Mondal, S.; Singh, R.D.; Patra, A.K.; Dwivedi, B.S. Changes in soil quality in response to short-term application of municipal sewage sludge in a typic haplustept under cowpea-wheat cropping system. Environ. Nanotechnology, Monit. Manag. 2015, 4, 37–41.

- Kumar, V.; Chopra, A.K. Accumulation and translocation of metals in soil and different parts of french bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) amended with sewage sludge. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2014, 92, 103–108.

- Rehman, R.A.; Rizwan, M.; Qayyum, M.F.; Ali, S.; Zia-ur-Rehman, M.; Zafar-ul-Hye, M.; Hafeez, F.; Iqbal, M.F. Efficiency of various sewage sludges and their biochars in improving selected soil properties and growth of wheat (Triticum aestivum). J. Environ. Manage. 2018, 223, 607–613.

- Rehman, R.A.; Qayyum, M.F. Co-composts of sewage sludge, farm manure and rock phosphate can substitute phosphorus fertilizers in rice-wheat cropping system. J. Environ. Manage. 2020, 259, 109700.

- Delibacak, S.; Voronina, L.; Morachevskaya, E.; Ongun, A.R. Use of sewage sludge in agricultural soils: Useful or harmful. Eurasian J. Soil Sci. 2020, 9, 126–139.

- Aoshima, K.; Fan, J.; Cai, Y.; Katoh, T.; Teranishi, H.; Kasuya, M. Assessment of bone metabolism in cadmium-induced renal tubular dysfunction by measurements of biochemical markers. Toxicol. Lett. 2003, 136, 183–192.

- FAO/WHO. Information and use in discussion related to contaminants and toxins in the GSCTFF. Jt. FAO/WHO Food Stand. Program. Codex Comm. Contam. Foods 2011, 1–90.

- Commission Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006 of 19 December 2006 Setting Maximum Levels for Certain Contaminants in Foodstuffs. In Text with EEA relevance; European Commission: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2006.

- Mazen, A.; Faheed, F.A.; Ahmed, A.F. Study of potential impacts of using sewage sludge in the amendment of desert reclaimed soil on wheat and jews mallow plants. Brazilian Arch. Biol. Technol. 2010, 53, 917–930.

- Moreno, J.L.; García, C.; Hernández, T.; Ayuso, M. Application of composted sewage sludges contaminated with heavy metals to an agricultural soil: Effect on lettuce growth. Soil Sci. Plant. Nutr. 1997, 43, 565–573.

- Kidd, P.S.; Domínguez-Rodríguez, M.J.; Díez, J.; Monterroso, C. Bioavailability and plant accumulation of heavy metals and phosphorus in agricultural soils amended by long-term application of sewage sludge. Chemosphere 2007, 66, 1458–1467.

- Lakhdar, A.; Iannelli, M.A.; Debez, A.; Massacci, A.; Jedidi, N.; Abdelly, C. Effect of municipal solid waste compost and sewage sludge use on wheat (Triticum durum): Growth, heavy metal accumulation, and antioxidant activity. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 90, 965–971.

- Moffat, A.J.; Armstrong, A.T.; Ockleston, J. The optimization of sewage sludge and effluent disposal on energy crops of short rotation hybrid poplar. Biomass Bioenergy 2001, 20, 161–169.

- Chang, A.C., Page. Developing Human Health-Related Chemical Guidelines for Reclaimed Waster and Sewage Sludge Applications in Agriculture; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002; p. 105.

- Moreno, J.L.; García, C.; Hernández, T.; Pascual, J.A. Transference of heavy metals from a calcareous soil amended with sewage-sludge compost to barley plants. Bioresour. Technol. 1996, 55, 251–258.

- Singh, R.P.; Agrawal, M. Effect of different sewage sludge applications on growth and yield of Vigna radiata L. field crop: Metal uptake by plant. Ecol. Eng. 2010, 36, 969–972.

- Antonious, G.F.; Kochhar, T.S.; Coolong, T. Yield, quality, and concentration of seven heavy metals in cabbage and broccoli grown in sewage sludge and chicken manure amended soil. J. Environ. Sci. Heal. Part. A Toxic/Hazardous Subst. Environ. Eng. 2012, 47, 1955–1965.

- Singh, R.P.; Agrawal, M. Use of sewage sludge as fertiliser supplement for Abelmoschus esculentus plants: Physiological, biochemical and growth responses. Int. J. Environ. Waste Manag. 2009, 3, 91–106.

- Latare, A.M.; Kumar, O.; Singh, S.K.; Gupta, A. Direct and residual effect of sewage sludge on yield, heavy metals content and soil fertility under rice-wheat system. Ecol. Eng. 2014, 69, 17–24.

- Düring, R.A.; Hoß, T.; Gäth, S. Depth distribution and bioavailability of pollutants in long-term differently tilled soils. Soil Tillage Res. 2002, 66, 183–195.

- Zhou, H.; Yang, W.T.; Zhou, X.; Liu, L.; Gu, J.F.; Wang, W.L.; Zou, J.L.; Tian, T.; Peng, P.Q.; Liao, B.H. Accumulation of heavy metals in vegetable species planted in contaminated soils and the health risk assessment. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2016, 13.

- Zhu, Y.; Yu, H.; Wang, J.; Fang, W.; Yuan, J.; Yang, Z. Heavy metal accumulations of 24 asparagus bean cultivars grown in soil contaminated with Cd alone and with multiple metals (Cd, Pb, and Zn). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 1045–1052.

- Rai, P.K.; Lee, S.S.; Zhang, M.; Tsang, Y.F.; Kim, K.H. Heavy metals in food crops: Health risks, fate, mechanisms, and management. Environ. Int. 2019, 125, 365–385.

- Krzesłowska, M. The cell wall in plant cell response to trace metals: Polysaccharide remodeling and its role in defense strategy. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2011, 33, 35–51.

- Probst, A.; Liu, H.; Fanjul, M.; Liao, B.; Hollande, E. Response of Vicia faba L. to metal toxicity on mine tailing substrate: Geochemical and morphological changes in leaf and root. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2009, 66, 297–308.

- Zhuang, P.; McBride, M.B.; Xia, H.; Li, N.; Li, Z. Health risk from heavy metals via consumption of food crops in the vicinity of Dabaoshan mine, South China. Sci. Total Environ. 2009, 407, 1551–1561.

- Loutfy, N.; Fuerhacker, M.; Tundo, P.; Raccanelli, S.; El Dien, A.G.; Ahmed, M.T. Dietary intake of dioxins and dioxin-like PCBs, due to the consumption of dairy products, fish/seafood and meat from Ismailia city, Egypt. Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 370, 1–8.

- Real, M.I.H.; Azam, H.M.; Majed, N. Consumption of heavy metal contaminated foods and associated risks in Bangladesh. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2017, 189.

- Türkdogan, M.K.; Fevzi, K.; Kazim, K.; Ilyas, T.; Ismail, U. Heavy metals in soil, vegetables and fruits in the endemic upper gastrointestinal cancer region of Turkey. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2002, 13, 175–179.

- Lentini, P.; Zanoli, L.; de Cal, M.; Granata, A.; Dell’Aquila, R. Lead and Heavy Metals and the Kidney, 3rd ed.2019; ISBN 9780323449427.

- Al-Saleh, I.; Al-Rouqi, R.; Elkhatib, R.; Abduljabbar, M.; Al-Rajudi, T. Risk assessment of environmental exposure to heavy metals in mothers and their respective infants. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2017, 220, 1252–1278.

- Navas-Acien, A.; Guallar, E.; Silbergeld, E.K.; Rothenberg, S.J. Lead exposure and cardiovascular disease—A systematic review. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, 472–482.

- Weisskopf, M.G.; Weuve, J.; Nie, H.; Saint-Hilaire, M.H.; Sudarsky, L.; Simon, D.K.; Hersh, B.; Schwartz, J.; Wright, R.O.; Hu, H. Association of cumulative lead exposure with Parkinson’s disease. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010, 118, 1609–1613.

- Mossa, A.W.; Bailey, E.H.; Usman, A.; Young, S.D.; Crout, N.M.J. The impact of long-term biosolids application (>100 years) on soil metal dynamics. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 720.

- Hosseini Koupaie, E.; Eskicioglu, C. Health risk assessment of heavy metals through the consumption of food crops fertilized by biosolids: A probabilistic-based analysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2015, 300, 855–865.

- Salem, H.M.; Abdel-Salam, A.; Abdel-Salam, M.A.; Seleiman, M.F. Phytoremediation of metal and metalloids from contaminated soil. In Plants Under Metal and Metalloid Stress: Responses, Tolerance and Remediation; Springer Nature Singapure: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; ISBN 9789811322426.

- Edelstein, M.; Ben-Hur, M. Heavy metals and metalloids: Sources, risks and strategies to reduce their accumulation in horticultural crops. Sci. Hortic. 2018, 234, 431–444.

- Pandey, V.C.; Bajpai, O. Phytoremediation: From Theory Toward Practice; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; ISBN 9780128139134.

- Polechońska, L.; Klink, A. Trace metal bioindication and phytoremediation potentialities of Phalaris arundinacea L. (reed canary grass). J. Geochemical Explor. 2014, 146, 27–33.

- Placek, A.; Grobelak, A.; Kacprzak, M. Improving the phytoremediation of heavy metals contaminated soil by use of sewage sludge. Int. J. Phytoremediation. 2016, 18, 605–618.

- Greger, M.; Landberg, T. Use of willow in phytoextraction. Int. J. Phytoremediation 1999, 1, 115–123.

- Schwartz, C.; Echevarria, G.; Morel, J.L. Phytoextraction of cadmium with Thlaspi caerulescens. Plant. Soil 2003, 249, 27–35.

- Fernando, A.L.; Barbosa, B.; Costa, J.; Papazoglou, E.G. Giant Reed (Arundo Donax l.): A Multipurpose Crop Bridging Phytoremediation with Sustainable Bioeconomy; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; ISBN 9780128028728.

- Suman, J.; Uhlik, O.; Viktorova, J.; Macek, T. Phytoextraction of heavy metals: A promising tool for clean-up of polluted environment? Front. Plant. Sci. 2018, 871, 1–15.

- Guerinot, M. Lou The ZIP family of metal transporters. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2000, 1465, 190–198.

- Ali, S.; Abbas, Z.; Rizwan, M.; Zaheer, I.E.; Yavas, I.; Ünay, A.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Bin-Jumah, M.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Kalderis, D. Application of floating aquatic plants in phytoremediation of heavy metals polluted water: A review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1927.

- Bais, S.S.; Lawrence, K.; Pandey, A.K. Phytoremediation Potential of Eichhornia crassipes (Mart.) Solms. Int. J. Environ. Agric. Biotechnol. 2016, 1, 210–217.

- Das, S.; Goswami, S.; Das Talukdar, A. Physiological responses of water hyacinth, eichhornia crassipes (Mart.) solms, to cadmium and its phytoremediation potential. Turkish J. Biol. 2016, 40, 84–94.

- Gunathilakae, N.; Yapa, N.; Hettiarachchi, R. Effect of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi on the cadmium phytoremediation potential of Eichhornia crassipes (Mart.) Solms. Groundw. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 7, 477–482.

- Çelebi, Ş.Z.; Ekin, Z.; Zorer, Ö.S. Accumulation and tolerance of Pb in some bioenergy crops. Polish J. Environ. Stud. 2018, 27, 591–596.

- Klang-Westin, E.; Eriksson, J. Potential of Salix as phytoextractor for Cd on moderately contaminated soils. Plant. Soil 2003, 249, 127–137.

- da Silva, P.H.M.; Poggiani, F.; Laclau, J.P. Applying Sewage Sludge to Eucalyptus grandis Plantations: Effects on Biomass Production and Nutrient Cycling through Litterfall. Appl. Environ. Soil Sci. 2011, 2011, 1–11.

- Leila, S.; Mhamed, M.; Heilmeier, H.; Kharytonov, M.; Wiche, O.; Moschner, C.; Onyshchenko, E.; Nadia, B. Fertilization value of municipal sewage sludge for Eucalyptus camaldulensis plants. Biotechnol. Reports 2017, 13, 8–12.

- Unterbrunner, R.; Puschenreiter, M.; Sommer, P.; Wieshammer, G.; Tlustoš, P.; Zupan, M.; Wenzel, W.W. Heavy metal accumulation in trees growing on contaminated sites in Central Europe. Environ. Pollut. 2007, 148, 107–114.