Lithium possesses the ability to depolarize the resting membrane potential of the cell. It has been proposed that lithium treats bipolar patients by membrane depo-larization of neuronal cells that is triggered by quantum tunneling of lithium ions through sodium channels when lithium reaches its therapeutic concentration.

- lithium

- membrane depolarization

- membrane potential

- cell death

- NLRP3

- SARS-CoV-2

- COVID-19

- cytokine storm

1. Introduction

Lithium possesses the ability to depolarize the resting membrane potential of the cell [28]. It has been proposed that lithium treats bipolar patients by membrane depolarization of neuronal cells that is triggered by quantum tunneling of lithium ions through sodium channels when lithium reaches its therapeutic concentration [29,30]. A consistent correlation between lithium actions and the effects of membrane depolarization on the cells can be constructed. Lithium and membrane depolarization have neuroprotective effects through enhancing the growth of neurons and inhibiting their death. This makes lithium very effective in treating bipolar patients [8,31–34]. Lithium and membrane depolarization can inhibit or stimulate the growth of cells in different ways according to their cell lines [8–10,35,36]. They also have immunomodulatory actions that affect the functions of immune cells [8,37–39]. Furthermore, they can effectively enhance wound healing and bone repair [8,40,41]. More interestingly, membrane depolarization is the trigger of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) and protein kinase B(Akt) activation [42], which leads to serine phosphorylation that inhibits glycogen synthase kinase-3-beta (GSK-3-beta) [43], which is an important target that is also inhibited by lithium by the same mechanism [44]. This indicates that lithium could mediate its cellular effects via membrane depolarization.

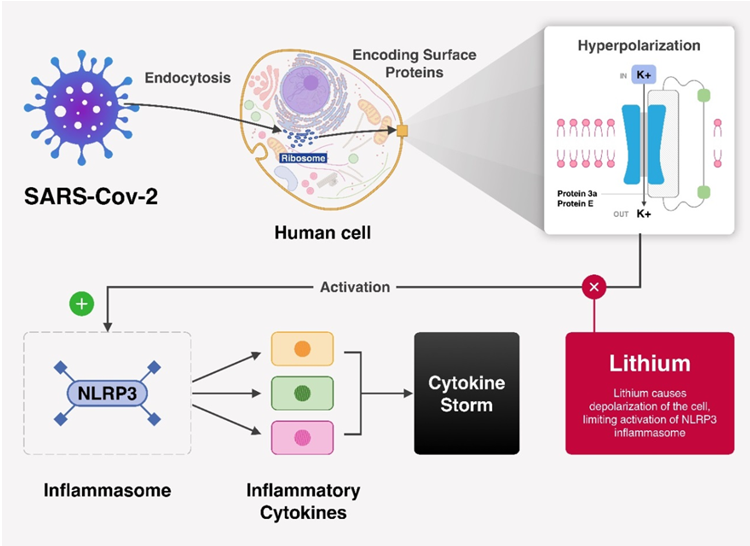

As stated in Section 2, it is clear that membrane hyperpolarization is a fundamental trigger for the release of the virus and its pathogenesis, as well as immune-system dysregulation. On the other hand, the ability of lithium ions to depolarize the membrane can be concluded from experimental and theoretical observations and the consistent correlation between actions of lithium and membrane depolarization. Therefore, lithium has the potential to reverse the hyperpolarization through the action of depolarization. Consequently, all the pathological processes mediated by hyperpolarization will be blocked and prevented. Figure 1 illustrates how membrane depolarization by lithium interrupts the activation of NLRP3.

Figure 1. A theoretical scheme of how lithium depolarization interrupts the cascade that leads to NLRP3 activation.

2. Role of Lithium in SARS-CoV-2

Lithium has an important immunomodulatory role in fighting SARS-CoV-2 by depolarizing the membrane potential when the ions are transported through the sodium channels such as TRPM4 and Nav1.5, which are present in the membranes of immune cells [45]. This role can be explained in the context of COVID-19 by the following points:

- Macrophages, the predominant driving cells of the cytokine storm [27], are modulated by membrane potential changes. It was found that membrane depolarization inhibits the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF and IL-6 [46,47]. Interestingly, lithium affects the polarization of macrophages and modulates their release of pro-inflammatory cytokines in a manner that favors the attenuation of the inflammatory process [37,38]. This supports the consistent correlation between the actions of lithium and the membrane potential changes.

- In regard to lymphocytes, it was found that lithium increases the production of antibodies from B-lymphocytes by membrane depolarization, which is an early step of B-lymphocyte activation [37–39]. This step is essential in fighting SARS-CoV because these antibodies work to block the virus’ entry [48]. Lithium can also augment the proliferation of T-lymphocytes [49–51] because membrane depolarization is required for T-lymphocyte activation [52,53]. On the other hand, hyperpolarization is also required to stimulate T-lymphocytes [52,53]. Hence, lithium might serve to inhibit T-lymphocyte activation and proliferation [37]. Moreover, lithium can modulate the secretion of interleukins from CD4+ and CD8+ lymphocytes. Both types of T-lymphocytes secrete IL-2 and IL-5 [54], and CD4+ cells also secrete IL-4, IL-6, IL-10, and IL-22 [54]. There is no clear consensus on the final effect of lithium on these interleukins secretions. However, we mention here the outcome obtained from the higher number of studies as the following [55]: 1. Lithium enhances the production of anti-inflammatory IL-2. 2. Lithium increases the levels of pro-inflammatory IL-4. 3. Many studies have demonstrated that lithium attenuates the production of the pro-inflammatory IL-6, but many studies also have shown that lithium enhances IL-6 secretion. 4. Lithium increases the production of the anti-inflammatory IL-10. Additionally, lithium decreases the anti-inflammatory IL-5 in co-cultured cortical cells and glial cells, but it increases its levels in co-cultured hippocampal cells and glial cells [56]. Also, lithium increased the levels of IL-22 in vitro [57], and this interleukin is implicated in pathogen defense, wound healing, and tissue reorganization [54]. Accordingly, it seems that lithium balances the regulation of the immune system in such a way that no over-activation takes place to damage the lung parenchyma, and no under-activation occurs to weaken the clearance of the virus from the body.

The immunomodulatory actions of lithium are important in the context of fighting coronavirus in terms of three aspects. First, lithium can mitigate the over-activated immune response, which is predominantly driven by macrophages and is responsible for the clinical deterioration and ARDS development. Second, inhibiting the pro-inflammatory cytokines will boost the function of T-lymphocytes [27] to clear the virus from the body. Third, lithium increases the production of neutralizing antibodies from B-lymphocytes that work to block the entry of the virus, and lithium can balance the activity of T-lymphocytes in the sense that no over-activation or under-activation takes place.

Based on the collective understanding presented in Sections 2 and 3, lithium has the potential to stop the progression of COVID-19, prevent its clinical deterioration, and decrease the number of patients requiring mechanical ventilation as part of ARDS or respiratory failure treatment. Also, it is concluded that lithium has the potential to regulate the immune response in a way that mitigates the over-activation of immune reactions, but preserves the capacity of immune cells to kill the virus.

Here, in the context of membrane depolarization induced by lithium, magnesium ions should be mentioned. Interestingly, magnesium also depolarizes the membrane potential [58–60]; hence magnesium can augment the antiviral actions of lithium. However, since the effect of membrane depolarization is determined by the ion transport through the sodium channels, lithium will have a higher tendency to depolarize the membrane potential because sodium channels are more selective for lithium than magnesium [61].

Reference (Editors will rearrange the references after the entry is submitted)

-

Adhikari, P.; Meng, S.; Wu, Y.J.; Mao, Y.P.; Ye, R.X.; Wang, Q.Z.; Sun, C.; Sylvia, S.; Rozelle, S.; Raat, H.; et al. Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak period: A scoping review. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2020, 9, 1–2.

-

WHO Says Coronavirus Situation ‘Worsening’ Available online: https://medicalxpress.com/news/2020-06-coronavirus-situation-worsening-worldwide.html (accessed on 11 June 2020).

-

Naqvi, A.; Fatima, K.; Mohammad, T.; Fatima, U.; Singh, I.K.; Singh, A.; Atif, S.M.; Hariprasad, G.; Hasan, G.M.; Hassan, M.I. Insights into SARS-CoV-2 genome, structure, evolution, pathogenesis and therapies: Structural genomics approach. Biochimic. Biophys. Acta BBA Mol. Basis Dis. 2020, 1866, 165878.

-

Yang, ; Peng, F.; Wang, R.; Guan, K.; Jiang, T.; Xu, G.; Sun, J.; Chang, C. The deadly coronaviruses: The 2003 SARS pandemic and the 2020 novel coronavirus epidemic in China. J. Autoimmun. 2020, 109, 102434.

-

Cascella, ; Rajnik, M.; Cuomo, A.; Dulebohn, S.C.; Di Napoli, R. Features, evaluation and treatment coronavirus (COVID-19). In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Tampa, FL, USA, 2020.

-

Castaño-Rodriguez, ; Honrubia, J.M.; Gutiérrez-Álvarez, J.; DeDiego, M.L.; Nieto-Torres, J.L.; Jimenez-Guardeño, J.M.; Regla-Nava, J.A.; Fernandez-Delgado, R.; Verdia-Báguena, C.; Queralt-Martín, M.; et al. Role of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus viroporins E, 3a, and 8a in replication and pathogenesis. MBio 2018, 9, e02325–e02417, doi:10.1128/mBio.02325-17.

-

Lu, ; Zheng, B.J.; Xu, K.; Schwarz, W.; Du, L.; Wong, C.K.; Chen, J.; Duan, S.; Deubel, V.; Sun, B. Severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus 3a protein forms an ion channel and modulates virus release. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 12540–12545.

-

Abdul Kadir, ; Stacey, M.; Barrett-Jolley, R. Emerging roles of the membrane potential: Action beyond the action potential. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1661.

-

Blackiston, J.; McLaughlin, K.A.; Levin, M. Bioelectric controls of cell proliferation: Ion channels, membrane voltage and the cell cycle. Cell Cycle 2009, 8,3527–3536.

-

Urrego, ; Tomczak, A.P.; Zahed, F.; Stühmer, W.; Pardo, L.A. Potassium channels in cell cycle and cell proliferation. Philos Trans. R Soc. B 2014, 369, 20130094.

-

Kito, ; Yamamura, H.; Suzuki, Y.; Ohya, S.; Asai, K.; Imaizumi, Y. Membrane hyperpolarization induced by endoplasmic reticulum stress facilitates Ca2+ influx to regulate cell cycle progression in brain capillary endothelial cells. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 14002SC, doi:10.1254/jphs.14002SC.

-

Muñoz-Planillo, ; Kuffa, P.; Martínez-Colón, G.; Smith, B.L.; Rajendiran, T.M.; Núñez, G. K+ efflux is the common trigger of NLRP3 inflammasome activation by bacterial toxins and particulate matter. Immunity 2013, 38, 1142–1153.

-

Fung, Y.; Yuen, K.S.; Ye, Z.W.; Chan, C.P.; Jin, D.Y. A tug-of-war between severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 and host antiviral defence: Lessons from other pathogenic viruses. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 558–570.

-

Tan, J.; Lim, S.G.; Hong, W. Regulation of cell death during infection by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus and other coronaviruses. Cell Microbiol. 2007, 9, 2552–2561.

-

Ren, ; Shu, T.; Wu, D.; Mu, J.; Wang, C.; Huang, M.; Han, Y.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhou, W.; Qiu, Y.; et al. The ORF3a protein of SARS-CoV-2 induces apoptosis in cells. Cell. Mol. Immunol. 2020, 17, 881–883.

-

Chen, Y.; Moriyama, M.; Chang, M.F.; Ichinohe, T. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus viroporin 3a activates the NLRP3 inflammasome. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 50.

-

Schoeman, ; Fielding, B.C. Coronavirus envelope protein: Current knowledge. Virol. J. 2019, 16, 69.

-

Verdiá-Báguena, ; Nieto-Torres, J.L.; Alcaraz, A.; DeDiego, M.L.; Torres, J.; Aguilella, V.M.; Enjuanes, L. Coronavirus E protein forms ion channels with functionally and structurally-involved membrane lipids. Virology 2012, 432, 485–494.

-

Nieto-Torres, L.; Verdiá-Báguena, C.; Jimenez-Guardeño, J.M.; Regla-Nava, J.A.; Castaño-Rodriguez, C.; Fernandez-Delgado, R.; Torres, J.; Aguilella, V.M.; Enjuanes, L. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus E protein transports calcium ions and activates the NLRP3 inflammasome. Virology 2015, 485, 330–339.

-

Li, ; Yuan, L.; Dai, G.; Chen, R.A.; Liu, D.X.; Fung, T.S. Regulation of the ER Stress Response by the Ion Channel Activity of the Infectious Bronchitis Coronavirus Envelope Protein Modulates Virion Release, Apoptosis, Viral Fitness, and Pathogenesis. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 3022.

-

Fung, S.; Liu, D.X. Coronavirus infection, ER stress, apoptosis and innate immunity. Front. Microbiol. 2014, 5, 296.

-

Minakshi, ; Padhan, K.; Rani, M.; Khan, N.; Ahmad, F.; Jameel, S. The SARS Coronavirus 3a protein causes endoplasmic reticulum stress and induces ligand-independent downregulation of the type 1 interferon receptor. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e8342.

-

Versteeg, A.; van de Nes, P.S.; Bredenbeek, P.J.; Spaan, W.J. The coronavirus spike protein induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and upregulation of intracellular chemokine mRNA concentrations. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 10981–10990.

-

Bianchi, ; Benvenuto, D.; Giovanetti, M.; Angeletti, S.; Ciccozzi, M.; Pascarella, S. Sars-CoV-2 Envelope and Membrane Proteins: Structural Differences Linked to Virus Characteristics? BioMed Res. Int. 2020, doi:10.1155/2020/4389089.

-

Kern, M.; Sorum, B.; Hoel, C.M.; Sridharan, S.; Remis, J.P.; Toso, D.B.; Brohawn, S.G. Cryo-EM structure of the SARS-CoV-2 3a ion channel in lipid nanodiscs. BioRxiv 2020, doi:10.1101/2020.06.17.156554.

-

Tomar, P.; Arkin, I.T. SARS-CoV-2 E protein is a potential ion channel that can be inhibited by Gliclazide and Memantine. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020, 530, 10–14.

-

Channappanavar, ; Perlman, S. Pathogenic human coronavirus infections: Causes and consequences of cytokine storm and immunopathology. In Seminars in Immunopathology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017; Volume 39, pp.529–539.

-

Carmeliet, E. Influence of lithium ions on the transmembrane potential and cation content of cardiac cells. J. Gen. Physiol. 1964, 47, 501–530.

-

Qaswal, B. Quantum Electrochemical Equilibrium: Quantum Version of the Goldman–Hodgkin–Katz Equation. Quantum Rep. 2020, 2, 266–277.

-

Qaswal, B. Lithium stabilizes the mood of bipolar patients by depolarizing the neuronal membrane via quantum tunneling through the sodium channels. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2020, 18, 214.

-

Plotnikov, Y.; Silachev, D.N.; Zorova, L.D.; Pevzner, I.B.; Jankauskas, S.S.; Zorov, S.D.; Babenko, V.A.; Skulachev, M.V.; Zorov, D.B. Lithium salts—Simple but magic. Biochemistry 2014, 79, 740–749.

-

Malhi, S.; Tanious, M.; Das, P.; Coulston, C.M.; Berk, M. Potential mechanisms of action of lithium in bipolar disorder. CNS Drugs 2013, 27, 135–153.

-

Cone, D.; Cone, C.M. Induction of mitosis in mature neurons in central nervous system by sustained depolarization. Science 1976, 192, 155–158.

-

Stillwell, F.; Cone, C.M.; JUNC. Stimulation of DNA synthesis in CNS neurones by sustained depolarisation. Nat. New Biol. 1973, 246, 110.

-

Vidali, ; Aminzadeh-Gohari, S.; Vatrinet, R.; Iommarini, L.; Porcelli, A.M.; Kofler, B.; Feichtinger, R.G. Lithium and Not Acetoacetate Influences the Growth of Cells Treated with Lithium Acetoacetate. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3104.

-

Li, ; Huang, K.; Liu, X.; Liu, J.; Lu, X.; Tao, K.; Wang, G.; Wang, J. Lithium chloride suppresses colorectal cancer cell survival and proliferation through ROS/GSK-3β/NF-κB signaling pathway. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2014, doi:10.1155/2014/241864.

-

Maddu, ; Raghavendra, P.B. Review of lithium effects on immune cells. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2015, 37, 111–125.

-

Bartnikowski, ; Moon, H.J.; Ivanovski, S. Release of lithium from 3D printed polycaprolactone scaffolds regulates macrophage and osteoclast response. Biomed. Mater. 2018, 13, 065003.

-

Monroe, G.; Cambier, J.C. B cell activation. I. Anti-immunoglobulin-induced receptor cross-linking results in a decrease in the plasma membrane potential of murine B lymphocytes. J. Exp. Med. 1983, 157, 2073–2086.

-

Pandit, ; Nesbitt, S.R.; Kim, D.Y.; Mixon, A.; Kotha, S.P. Combinatorial therapy using negative pressure and varying lithium dosage for accelerated wound healing. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. 2015, 44, 173–178.

-

Bose, ; Fielding, G.; Tarafder, S.; Bandyopadhyay, A. Understanding of dopant-induced osteogenesis and angiogenesis in calcium phosphate ceramics. Trends Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 594–605.

-

Chatterjee, ; Browning, E.A.; Hong, N.; DeBolt, K.; Sorokina, E.M.; Liu, W.; Birnbaum, M.J.; Fisher, A.B. Membrane depolarization is the trigger for PI3K/Akt activation and leads to the generation of ROS. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2012, 302, H105–H114.

-

Lee, I.; Seo, M.; Kim, Y.; Kim, S.Y.; Kang, U.G.; Kim, Y.S.; Juhnn, Y.S. Membrane depolarization induces the undulating phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of glycogen synthase kinase 3β, and this dephosphorylation involves protein phosphatases 2A and 2B in SH-SY5Y human neuroblastoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 22044–22052.

-

Chuang, M.; Wang, Z.; Chiu, C.T. GSK-3 as a target for lithium-induced neuroprotection against excitotoxicity in neuronal cultures and animal models of ischemic stroke. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2011, 4, 15.

-

Feske, ; Wulff, H.; Skolnik, E.Y. Ion channels in innate and adaptive immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2015, 33, 291–353.

-

Erndt-Marino, ; Hahn, M.S. Membrane potential controls macrophage activation. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2016, 4, 10–3389.

-

Haslberger, ; Romanin, C.; Koerber, R. Membrane potential modulates release of tumor necrosis factor in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated mouse macrophages. Mol. Biol. Cell 1992, 3, 451–460.

-

Hsueh, R.; Huang, L.M.; Chen, P.J.; Kao, C.L.; Yang, P.C. Chronological evolution of IgM, IgA, IgG and neutralisation antibodies after infection with SARS-associated coronavirus. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2004, 10, 1062–1066.

-

Kucharz, J.; Sierakowski, S.; Staite, N.D.; Goodwin, J.S. Mechanism of lithium-induced augmentation of T-cell proliferation. Int. J. Immunopharmacol. 1988, 10, 253–259.

-

Borkowsky, ; Shenkman, L.; Rausen, A. T-lymphocyte cycling in human cyclic neutropenia: Effects of lithium in vitro and in vivo. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1982, 23, 586–592.

-

Bray, ; Turner, A.R.; Dusel, F. Lithium and the mitogenic response of human lymphocytes. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1981, 19, 284–288.

-

Kiefer, ; Blume, A.J.; Kaback, H.R. Membrane potential changes during mitogenic stimulation of mouse spleen lymphocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1980, 77, 2200–2204.

-

Daniele, P.; Holian, S.K. A potassium ionophore (valinomycin) inhibits lymphocyte proliferation by its effects on the cell membrane. Proc. Natl Acad Sci. USA 1976, 73, 3599–3602.

-

Akdis, ; Aab, A.; Altunbulakli, C.; Azkur, K.; Costa, R.A.; Crameri, R.; Duan, S.; Eiwegger, T.; Eljaszewicz, A.; Ferstl, R.; et al. Interleukins (from IL-1 to IL-38), interferons, transforming growth factor β, and TNF-α: Receptors, functions, and roles in diseases. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2016, 138, 984–1010.

-

Nassar, ; Azab, A.N. Effects of lithium on inflammation. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2014, 5, 451–458.

-

De-Paula, V.; S. Kerr, D.; Scola, G.; F. Gattaz, W.; V. Forlenza, O. Lithium distinctly modulates the secretion of pro-and anti-inflammatory interleukins in co-cultures of neurons and glial cells at therapeutic and sub-therapeutic concentrations. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2016, 13, 848–852.

-

Himmerich, ; Bartsch, S.; Hamer, H.; Mergl, R.; Schönherr, J.; Petersein, C.; Munzer, A.; Kirkby, K.C.; Bauer, K.; Sack, U. Impact of mood stabilizers and antiepileptic drugs on cytokine production in-vitro. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2013, 47, 1751–1759.

-

Dribben, H.; Eisenman, L.N.; Mennerick, S. Magnesium induces neuronal apoptosis by suppressing excitability. Cell Death Dis. 2010, 1, e63.

-

Stanojevic, ; Lopicic, S.; Spasic, S.; Vukovic, I.; Nedeljkov, V.; Prostran, M. Effects of high extracellular magnesium on electrophysiological properties of membranes of Retzius neurons in leech Haemopis sanguisuga. J. Elementol. 2016, 21, 221–230.

-

Barjas Qaswal, Magnesium Ions Depolarize the Neuronal Membrane via Quantum Tunneling through the Closed Channels. Quantum Rep. 2020, 2, 57–63.

-

Sun, Y.M.; Favre, I.; Schild, L.; Moczydlowski, E. On the structural basis for size-selective permeation of organic cations through the voltage-gated sodium channel: Effect of alanine mutations at the DEKA locus on selectivity, inhibition by Ca2+ and H+, and molecular sieving. J. Gen. Physiol. 1997, 110, 693–715.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/scipharm89010011