Design science (DS) approaches have been emerging in engineering, management and other disciplines operating at the interface between design research and the natural or social sciences. Based on a state-of-the-art review of how DS is applied by management researchers, we develop a DS methodology for design-oriented disciplines that tend to adopt a rather intuitive notion of theory.

- design methodology

- theory

- design science

- design research

- validation

- management studies

- framing

- generativity

- research methodology

Herbert Simon’s seminal work The Sciences of the Artificial [1] has inspired the rise of design science (DS) approaches. DS has thus been emerging in engineering, information systems, organization and management studies, and entrepreneurship research. As a result, a growing number of scholars have been applying DS methods. However, research informed by DS raises major challenges, especially in disciplines in which scholarly status and legitimacy have been tied to the rigor of their knowledge base. Accordingly, the methodology of the natural and social sciences almost completely drove out the (pragmatist) design approach from engineering as well as business schools in the 1950s and 1960s, primarily because scholars and deans hankered after academic respectability, with the natural and social sciences as their main role models.

Subsequently, design research started flourishing in engineering and related disciplines despite this initial setback, but the field of management continues to suffer from its overcompensation for past scars of academic insecurity. That is, a vast majority of management scholars avoid doing problem-solving design work and focus on developing explanatory-descriptive theories. That is, combining design and science is very much like “mixing oil with water” [2] : it is rather easy to describe the intended outcome but rather difficult to produce it. Moreover, the task of mixing oil and water is not completed when the two components are mixed; left to themselves, they will start separating again. The current intellectual stasis of management scholarship and its growing detachment from business practice underline how difficult it is to mix science and design.

A major challenge in DS appears to arise from the dual role of theory. That is, theories can shape the interplay between the (empirical) world and its conceptual representation in two ways: one can focus on developing a theory of the world by means of constructs and models describing and explaining it, or alternatively, develop a theory for the world and use it as a gateway for discovering any objects behind it or creating entirely new objects. This theory of-for distinction appears to divide scholars in the field of management—to the extent that they tend to limit the use of theory to one or the other. To clearly distinguish the two, we refer in this paper to theorizing when developing theories of management practices and to framing in case of theories for (generating) these practices.

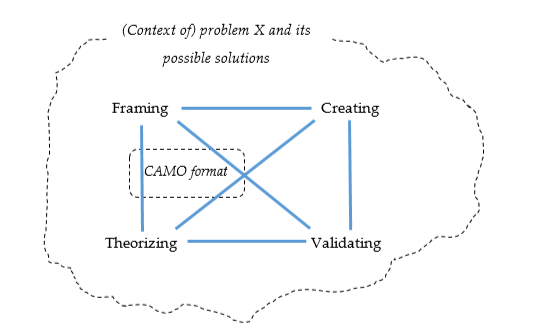

The need to forge a seamless connection between “what is” and “what could be” raises fundamental challenges for management scholars: the science mode is retrospective in making sense of the world as it is, and the design mode is prospective in envisioning and creating a future state of the world. In Figure 1, we outline a methodological framework that connects these modes.

DS focuses on solving problems, that is, changing extant systems and practices into desired ones. However, a DS approach typically treats the initial situation/problem as ill-defined, which at that stage also blurs the line between problem and context. Thus, a key step in any DS project is to frame and theorize about the problem and the problem-solving process. The frame serves as a gateway to creating and validating (the constructs and models underlying the) solutions.

In the framework outlined in Figure 1, framing refers to the act of exploring which (set of) construct(s) can provide a gateway for discovering and understanding the problem and solution space. Framing can involve individual cognition as well as the social construction of a particular problem/solution space. The framing notion resonates well with those emphasizing that theory development is an act of creative discovery and is pivotal in many DS studies reviewed.

Creating in DS involves the act of conceiving and realizing a new(ly perceived) artifact such as a strategy practice, entrepreneurial practice, intervention strategy or managerial tool. Framing and creating activity often go together, with many iterations back and forth. Most work by management practitioners does not go beyond this design space, especially when they create solutions within existing frames or when these frames undergo only minor changes to facilitate decisions on solutions.

The science mode in Figure 1 is further disentangled into theorizing and validating activities. Theorizing is about developing key concepts into well-defined constructs and formulating causal propositions and models which are generalizable as well as applicable to individual cases. Most of the DS studies reviewed earlier engage in some form of theorizing, although none of these studies focus on theoretical output as such. Figure 1 implies that theorizing not only guides and is affected by validation efforts but also interacts with framing and creating activity.

Finally, validating in DS involves the evaluation of (preliminary) frames or artifacts. Venable and coauthors [3] mapped the various validation methods in terms of two dimensions: ex-ante and ex-post evaluation (i.e., prior to versus after creating the frame/artifact) and naturalistic and artificial evaluation (e.g., field studies versus intervention/pilot studies). Artificial evaluation can be further differentiated in “alpha tests” in which the designer assesses whether and how the artifact performs in the (initial) setting where it was created, and “beta tests” in which others implement and assess the artifact in other settings. Overall, methods for artificial validation serve to assess whether and why the created artifact performs as expected—for example, in terms of usability, reliability, fairness and productivity. Naturalistic methods are more appropriate for testing theoretical propositions and models—in terms of their internal and external validity, reliability and generalizability.

Notably, the framing, creating, validating and theorizing acts appear to be complementary and feed on each other. For example, to be able to theorize in terms of a causal model, one first must explore what the most appropriate conceptual framing of the problem at hand is. In their use of theory, scholars can thus act as both scientists and designers; that is, they can aim to develop a theoretical representation of the problem as it is and/or use a conceptual frame to explore potential future solutions.

Figure 1. Framing, theorizing, creating and validating in design science, including the role of CAMO knowledge (source: Romme & Dimov 2021).

Figure 1 also serves to demonstrate the potential role of CAMO-formatted knowledge in connecting the four DS activities. CAMO propositions, also known as design rules, are especially instrumental in connecting the framing and theorizing acts but can also help connect the (emerging) body of knowledge that arises from framing and theorizing to creating and validating solutions (or other artifacts). Notably, the framework in Figure 1 does not explicitly refer to “what” is framed, created, theorized and validated. In this respect, DS researchers tend to embrace a broad set of potential artifacts, such as management practices, tools, constructs, models, (research) methods, conceptual frameworks, and design principles. While many of these artifacts can be the output of any of the four activities in Figure 1 and be used as input in subsequent activities, the DS studies reviewed tend to pay much more attention to the development of new practices and tools than to theoretical constructs and models, probably due to the problem-solving orientation of DS work.

The research cycle in Figure 1 appears to have no formal starting point, so one can start anywhere. For example, design-oriented practitioners often start with generating “workable knowledge solutions without having a fully formed theoretical understanding of the organizational components or systems they are designing.”[4] That is, the problem is first framed, which informs the creation of initial (ideas for) solutions; these solutions are then validated, for example, by pilot-testing them in one or two sites within the organization, which fuels efforts to theorize about the underlying causal relations. Alternatively, DS work can also start with theorizing, for example, by reviewing the literature on a particular (theoretical or practical) problem, including an assessment of the validation (evidence base) of various models and practices identified in the literature; subsequently, they frame a direction for problem-solving and create a solution prototype that then needs to be tested (validated), which typically invites a number of iterations in the entire research cycle. Other work informed by DS may cover only parts of the cycle, leaving the remaining activities to future work; for example, review studies of a particular problem area can focus on synthesizing existing theories and their validation in the form of a set of design propositions that inform design and intervention efforts in subsequent studies.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/designs5010013

References

- Simon, H.A.. The Sciences of the Artificial (3rd ed.); MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 1996; pp. 1-123.

- Simon, H.A.; The business school: A problem in organizational design. J. Manag. Stud. 1967, 4, 1-16, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.1967.tb00569.x.

- Venable, J., Pries-Heje, J. & Baskerville, R.; A comprehensive framework for evaluation in design science research. Lect. Notes Comput. Sci. 2012, 7286, 423-438, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-29863-9_31.

- Hodgkinson, G.P. & Healey, M.P.; Toward a (pragmatic) science of strategic intervention: Design propositions for scenario planning. Organization Studies 2008, 29, 435-457, https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840607088022.