Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Biochemistry & Molecular Biology

Exosomes are intrinsic cell-derived membrane vesicles in the size range of 40–100 nm, serving as great biomimetic nanocarriers for biomedical applications. These nanocarriers are known to bypass biological barriers, such as the blood–brain barrier, with great potential in treating brain diseases. Exosomes are also shown to be closely associated with cancer metastasis, making them great candidates for tumor targeting. However, the clinical translation of exosomes are facing certain critical challenges, such as reproducible production and in vivo tracking of their localization, distribution, and ultimate fate. Recently, inorganic nanoparticle-loaded exosomes have been shown great benefits in addressing these issues.

- exosomes

- inorganic nanoparticles

- bioimaging

- biomimetic nanocarriers

- theranostics

1. Introduction

Exosomes are intrinsic cell-derived membrane vesicles in a size range of 40–100 nm, and are naturally secreted by different cells [1,2]. Typically, exosomes contain biological components from the parental cells, such as mRNA, transporting proteins, or proteins associated with specific functions of the secreting cells [1,2]. Because of the contents of signaling molecules, optimal sizes, and membrane coatings, exosomes are known to have the ability to bypass biological barriers, including the blood–brain barrier, serving as powerful drug and gene therapy transporters [3]. Exosomes are also known to enhance cell proliferation [4], and are closely associated with cancer metastasis [5,6]; thus, tumor cell-derived exosomes intrinsically exhibited tumor targeting ability. Therefore, exosomes have been extensively studied as nanocarriers for drug delivery [7,8,9], where the cargos can be either introduced by treating parental cells with cargos of interests or loading cargos into exosomes post exosome isolation [10]. The potential benefits of exosomes have been demonstrated in various applications, such as cancer metastasis [11,12], musculoskeletal disorders [13], and nerve repair [14,15].

Despite the great potentials of exosomes, two critical challenges in exosome field remain: reproducible preparation and effective in vivo exosome tracking for therapeutic applications. Even though several techniques have been developed for tracking exosomes [16], limitations remain depending on the imaging modalities. For example, optical imaging by labeling exosomes with fluorescence molecules are widely utilized [16]. Fluorescence imaging is a highly sensitive and cost-effective imaging technique, but it suffers from deep tissue penetration, and background interferences. Positron emission tomography (PET) is a sensitive in vivo imaging technique, but it has limited usage in long-term tracking because of the short lifetime of the radioactive tracers. Inorganic nanoparticles provide many advantages as imaging probes, such as highly reproducible preparation and functionalization methods, long-term tracking ability, and potential of multifunctionality. For instance, iron oxide nanoparticles have been long studied as contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [17]. In contrast, gold (Au) nanoparticles have been explored as effective contrast agents for computerized tomography (CT) [18]. In addition, inorganic nanoparticles can serve as a means to deliver therapeutic effects, such as Au nanocages for photothermal therapy [19]. Therefore, loading exosomes with inorganic nanoparticles provides a great strategy for in vivo tracking and therapy. In addition, it was recently demonstrated that iron oxide nanoparticles with rationally designed surface coatings were used for effective removal of other biological components, assisting exosome purification [20].

2. Applications of Inorganic Nanoparticle-Loaded Exosomes

Inorganic nanoparticle-loaded exosomes have been explored for numerous applications, including in vivo tracking, simultaneous imaging and therapy, bio-distribution analysis, etc. [39,40]. The inorganic nanoparticles are normally used as contrast agents or imaging probes for certain imaging modalities, such as iron oxide nanoparticles for MRI and MPI, Au nanoparticles for CT imaging, QDs for fluorescence imaging, or Au/Ag nanoparticles for surface enhanced Raman spectrometry (SERS) detection. Additionally, these inorganic nanoparticles can serve as a means to deliver therapy, such as magnetic nanoparticles for magnetic hypothermia or nanoparticles with NIR absorbance for photothermal therapy. This section will mainly discuss the potential of nanoparticle-loaded exosomes in in vivo tracking using different imaging modalities and therapy.

2.1. Inorganic Nanoparticle-Loaded Exosomes for Bioimaging

For inorganic nanoparticle-loaded exosomes, the inorganic nanoparticles were primarily used as contrast agents or imaging probes to track exomes in targeting, trafficking, or distributions [17,29]. Among different imaging modalities, MRI and CT imaging are the most attractive because of their imaging resolution, well-studied inorganic nanoparticle contrast agents, and noninvasive nature of the techniques. Even though QDs have great potential in fluorescence imaging, their in vivo applications have been limited by the deep tissue penetration and background interferences.

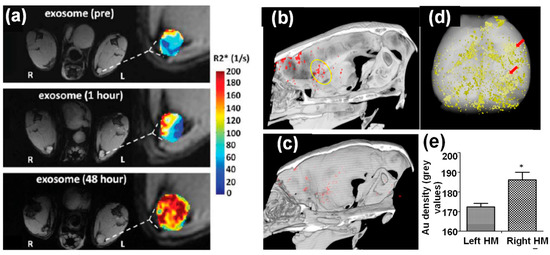

As a noninvasive and non-ionizing imaging technique, MRI requires contrast agents for enhanced imaging resolution where iron oxide nanoparticles serve as a great option [41]. Even though gadolinium-based complexes are clinical options as MRI contrast agents, loading magnetic nanoparticles within exosomes have been primarily studied for exosome imaging because of their high relaxivity and easy functionalization [41]. For example, 5 nm iron oxide nanoparticles loaded exosomes derived from B16-F10 cells were used to track the localization of exosomes in lymph nodes [42]. These iron oxide nanoparticle-loaded exosomes were introduced into mice via footpad injection. After 48 h, preferential accumulation of those exosomes was observed at the resident structural regions of the lymph node, indicated by significant signal enhancement of the T1-weighted MR images (Figure 4a). The effectivity of using MR imaging to track iron oxide nanoparticle-loaded exosomes was also demonstrated by adipose stem cell-derived vesicles loaded with ultrasmall iron oxide nanoparticles [43]. In vivo MR images clearly detected those iron oxide nanoparticle-loaded exosomes in the muscular tissue after intramuscular injection. In addition to serving as MRI contrast agents, magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles are also great tracers for magnetic particle imaging (MPI), an emerging imaging modality for in vivo tomographic imaging with minimal background interference [44]. MPI has been used to track iron oxide nanoparticle-loaded exosomes derived from metastatic breast cancer, MDA-MB231 cells. Those cancer cell-derived exosomes were effectively accumulated at tumor sites and were taken up by hypoxic cancer cells [34].

Figure 4. (a) In vivo MR imaging of mice injected with iron oxide nanoparticle-loaded exosomes derived from melanoma cells. After 48 h footpad injection, the T1-weighted images and R2* mapping clearly suggested accumulation of exosomes in lymph node [42]. (b–e) In vivo CT imaging of Au nanoparticle-loaded exosomes after intranasal administration into mice with acute striatal stroke: (b) a CT image 24 h post-administration (the ischemic region is indicated by the yellow circle), (c) a CT image of control animal with saline injection, (d) ex vivo CT imaging and Au quantification within the animal brain 24 h post administration, and (e) CT analysis of Au density of left and right hemispheres (note: stroke was introduced in the right hemisphere) [32].*: (p < 0.05).

CT imaging is a cost-effective, highly accessible, and efficient imaging modality with high temporal and spatial resolution. In addition to clinically used iodine-based compounds, Au nanoparticles have been explored extensively as CT contrast agents because of their high imaging resolution and demonstrated safety in preclinical studies [18]. Therefore, Au nanoparticle-loaded exosomes can be effectively tracked by CT imaging in vivo. For example, bone marrow MSC-derived exosomes labeled with glucose-coated Au nanoparticles were introduced into mice with acute striatal stroke via intranasal administration. These exosomes showed preferential accumulation inside the brain compared to intravenous injection. In addition, in vivo CT imaging suggested elective localization of these exosomes at stroke region 24 h post injection (Figure 4b–e), which was further verified by fluorescence imaging using a fluorescent marker [32]. CT imaging using the same type of Au nanoparticle-loaded exosomes further demonstrated their great potential in targeting and accumulating at different brain pathologies, including stroke, autism, Parkinson’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease using pathologically relevant murine models up to 96 h post administration [45]. In contrast, healthy control animals showed a diffuse migration pattern and clearance of these exosomes by 24 h. The targeting mechanism of these exosomes was hypothesized to be inflammatory-driven, where MSC derived exosomes were selectively taken up by neuronal cells, but not glial cells, in the pathological regions [45]. The ability of those Au nanoparticle-loaded exosomes penetrating the BBB after injection was key to the brain accumulation.

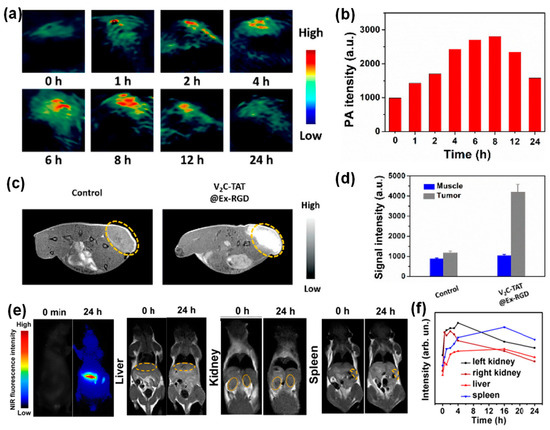

Another major advantage of inorganic nanoparticles is easy engineering for multi-functionality, allowing for dual mode tracking or simultaneous imaging and therapy. For example, cell-derived vesicles loaded with Au-iron oxide nanoparticles enabled both NIR fluorescence and MR imaging [46]. In another example, V2C QDs were successfully loaded into exosomes derived from MCF-7 breast cancer cells via electroporation [30]. Here, the QDs were modified with TAT peptides for nucleus targeting and the exosomes were functionalized with Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) peptide for cell targeting. These exosomes exhibited distinct NIR absorbance from V2C QDs, serving as great contrast agents for photoacoustic imaging (PAI). PAI uses a radio frequency-pulsed laser to irritate the region of interest, and the thermal expansion caused by the absorbed heat leads to acoustic wave detectable by ultrasounds for an image [30]. Figure 5a showed in vivo PA images of MCF-7 breast tumor-bearing mice at different times post injection of these V2C QD-loaded and functionalized exosomes. The PA signal reached to a maximum around 8 h at the tumor site. The PA signal quantification agreed well with the imaging observation (Figure 5d). Additionally, V2C QDs can serve as MRI contrast agents due to the 3D electronic configuration of V4+ and quantum confinement, leading to multi-modal imaging. Figure 5c shows the T1-weighted MR images of MCF-7 breast tumor-bearing mice 24 h post-exosome injection. Significant MR signal enhancement was observed compared to the control mice with saline injection, which was consistent with the MR signal quantification results (Figure 5d).

Figure 5. Dual imaging modalities with inorganic nanoparticle-loaded exosomes: (a–d) in vivo imaging of MCF-7 breast tumor-bearing mice after intravenous injection of V2C QD-loaded exosomes (a,b) PA images and quantified PA intensities of tumor sites at different times, (c,d) T1-weighted MR images and quantified MR signals of tumor sites 24 h post injection [30]. (e) NIR fluorescence and T1-weighted images of mouse liver, kidneys, and spleen at 0 h and 24 h post injection of Ag2Se@Mn QD-labeled exosomes. (f) MR signal quantification in mouse liver, kidneys, and spleen after injection of Ag2Se@Mn QD-labeled exosomes [31].

In another study, NIR QDs, silver selenium (Ag2Se), were magnetically functionalized with manganese ion (Mn2+), leading to magnetic and fluorescent bifunctional nanoparticles [31]. Subsequently, these nanoparticles were introduced into exosomes derived from several types of cancer cells, such as human oral squamous cell carcinoma (CAL27) cells, human lung epithelial carcinoma (A549) cells, human breast cancer (MCF-7) cells, and human immortalized noncancerous keratinocytes (HaCaT) cells through electroporation. It was shown that the nanoparticle loading efficiency was not affected by the exosome secreting cell types and the extremely size of these QDs led to over 90% loading efficiency. These magnetic Ag2Se-labeled exosomes enabled dual-mode tracking with fluorescence and MRI [31]. Figure 5e shows the NIR fluorescence and T1-weighted images of mouse liver, kidneys, and spleen at 0 h and 24 h post injection of Ag2Se@Mn QD-labeled exosomes. The NIR images showed significant signal enhancement compared to the control, while the MR signal enhancement was not profound likely do to the low density of manganese on the QD surfaces. The MR signal quantification at those organs after injection of the Ag2Se@Mn QD-labeled exosomes was in line with the imaging observation in Figure 5f.

In addition to in vivo tracking, inorganic nanoparticle-loaded exosomes were explored for cellular sensing. For example, Au nanoparticle-loaded exosomes derived from Hela cells were shown to be SERS active. The cellular uptake and intracellular fates of those can be monitored by SERS [47].

2.2. Inorganic Nanoparticle Loaded Exosomes for Theranostic Applications

Besides exosome tracking with different imaging modalities, inorganic nanoparticle-loaded exosomes have been explored as a tool for simultaneous imaging and therapy [23]. To this end, the therapeutic function was achieved by either encapsulating therapeutic molecules into the inorganic nanoparticles [37] or using inorganic nanoparticles directly as a means to induce therapy, such as photothermal therapy [30]. For example, doxorubicin (DOX)-loaded silicon porous nanoparticles were successfully loaded inside exosomes derived from human hepatocarcinoma Bel7402 cells. The intrinsic fluorescent properties of silicon allowed for exosome tracking with fluorescence imaging and DOX molecules trapped inside silicon pores delivered therapeutic effects. These tumor cell-derived exosomes showed enhanced tumor accumulation with deep tumor penetration after being injected into tumor-bearing mice [37]. The antitumor activities of these exosomes were demonstrated in subcutaneous transplantation tumor model, orthotropic tumor model, and advanced metastatic tumor model, where the anticancer ability of these exosomes was attributed to the cancer stem cell targeting and killing.

In addition to drug encapsulation, inorganic nanoparticles themselves can serve as a means for cancer therapy. For example, MSC-derived exosomes loaded with 40 nm hollow Au nanoparticles allowed for direct monitoring of exosome trafficking between cells [48]. In particular, these exosomes only targeted the cell type of origin when comparing different cell types, such as MSCs, monocytes, and melanoma cells. These hollow Au nanoparticles exhibited near IR absorption (700–100 nm). Therefore, these hollow Au nanoparticle-loaded exosomes were responsive to NIR radiation and induced selective cell death through a photothermal effect. In another study, V2C QDs-loaded exosomes not only enabled PAI and MRI imaging, but also exhibited high effectiveness in photothermal therapy in vitro under near IR–II laser irradiation [30]. Significant apoptosis of MCF cells treated with V2C QDs-loaded exosomes was observed under 1064 nm laser irradiation of 0.96 W cm−2 power intensity for 10 min. This NIR laser irradiation led to a temperature increase up to 45 °C. The in vivo photothermal effects were also observed in tumor-bearing mice with intravenous injection of the V2C QDs-loaded exosomes. Specifically, animal groups with the injection of V2C QDs-loaded exosomes showed evident temperature increase at the tumor sites and significant tumor growth repression under laser irradiation (Figure 6a–c). The IR thermal images and temperature changes at the tumor sites clearly demonstrated the temperature increase after laser irradiation (10 min 1064 nm, 0.96 W cm−2) as shown in Figure 6a,b. Figure 6c shows the comparison of the tumor growth curves of the MCF-7 tumor-bearing mice in different groups, suggesting that the RGD and TAT peptide functionalization greatly enhanced the efficiency of the photothermal therapy [30]. In addition, no adverse side effects were observed, indicated by the minimal animal weight fluctuation and tissue damage.

Figure 6. (a) IR thermal images and (b) the corresponding temperature changes at the tumor sites of MCF-7 tumor-bearing mice under 1064 nm laser irradiation. (c) Relative tumor growth curves of the MCF-7 tumor-bearing mice in different groups [30]. (d–f) In vivo bioluminescence imaging for the 14-day growth of xenografts of 4T1-Fluc-eGFP cells implanted in nude mice post administration of Au-Iron oxide nanoparticle-loaded exosomes. (d–f) In vivo biodistribution and anti-tumor properties of tumor cell derived exosomes loaded with Au-iron oxide nanoparticles and anti-miR-21 in combination with DOX. The bioluminescence images of animals treated with exosomes without DOX (d) and with DOX (e) at days 1, 4, 8, and 12, (f) biodistribution of anti-miR-21 in different organs of animals 12 days after treatment with 3 consecutive doses (days 1, 4, and 8) [46].

Another multi-functional nanocarrier was created by loading mouse breast cancer cells-derived exosomes with Au-iron oxide hybrid nanoparticles and therapeutic agents (miRNA and DOX) [46]. This nanoplatform provided an excellent multimodal contrast agent for T2-weighted MR imaging, combined chemo-sensitizing miRNA, and photothermal effects. These exosomes exhibited improved tumor-specific targeting with minimal immune responses. In vivo biodistribution and anti-tumor properties of these tumor cell derived exosomes loaded with Au-iron oxide nanoparticles and anti-miR-21 with/without DOX showed distinct therapeutic effects (Figure 6d,e). This observation suggested that anti-miR-21 delivery provided additive effects to DOX, and reduced DOX resistance in breast cancer cells. The co-delivery of anti-miR-21 with DOX yielded a three-fold higher cell kill efficiency than using DOX alone. The quantification of anti-miR-21 suggested a preferable localization of those exosomes in 4T1 tumors as compared with other organs (Figure 6g).

Furthermore, iron oxide nanoparticles are able to generate heat under an alternating magnetic field (AMF), so-called magnetic hyperthermia. Iron oxide loaded exosomes derived from human MSCs exhibited tumor targeting and accumulation ability [49], where iron oxide nanoparticles were incorporated inside exosomes after those nanoparticles were endocytosis by MSCs. After secretion, those exosomes simultaneously loaded with iron oxide nanoparticles and mRNA. Those exosomes were easily taken up by tumor cells in vitro and caused cell death under AMF. Mouse MCS-derived exosomes loaded with citrate-coated iron oxide nanoparticles via biological pathways showed increased activation and migration ability of macrophage, suggesting that loading of iron oxide nanoparticles enhanced the immunoregulatory properties of the vesicles from MSCs [50]. All these studies suggested the great potential of inorganic nanoparticle-loaded exosomes in therapeutic applications.

2.3. Inorganic Nanoparticle-Loaded Exosomes for Other Applications

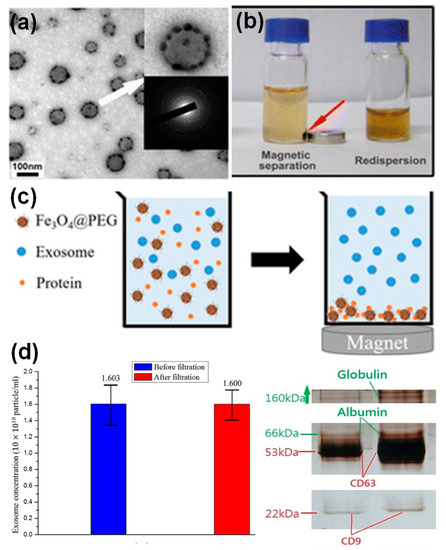

In addition to bioimaging and therapy, exosomes incorporated with nanoparticles, in particular, magnetic nanoparticles have been applied for enrichment and purification. For example, transferrin functionalized iron oxide nanoparticles have been linked to the surface Tf receptors of reticulocyte-derived exosomes from blood serum via Tf–Tf receptor interactions [51]. The decoration of multiple iron oxide nanoparticles on an exosome surface resulted in enhanced magnetic response of those exosomes to an external magnetic field. Subsequently, a significant increase in the exosome yield (~100 times) was obtained compared to exosome yields from cell cultures. Figure 7a,b showed the morphology of the iron oxide nanoparticle decorated exosomes, and their response to an external magnet. Alternatively, iron oxide nanoparticles have been applied to remove serum proteins via non-specific adsorption, leaving a cleaner exosome solution for further isolation and purification [20]. It is well known that nanoparticles with various surface coating nonspecifically adsorb serum proteins [52], which is normally considered a drawback of nanoparticles in drug delivery. In a recent study, the protein adsorption on nanoparticle surface was utilized in a positive way where PEG-coated iron oxide nanoparticles were applied for exosome purification [20]. Figure 7c shows the purification principle, which was tested using exosome solutions containing different protein supplements. The exosome concentration before and after nanoparticle treatment was not evidently altered, suggesting a minimal loss of exosomes (Figure 7d). SDS-PAGE gel of the purified exosomes demonstrated the effective removal of serum albumin and immunoglobulin proteins from solutions (Figure 7e). This study suggested that nanoparticles could offer another purification strategy for exosome preparation.

Figure 7. Iron oxide nanoparticles for exosome enrichment: a TEM image (a) and magnetic response (b) of Tf functionalized iron oxide decorated exosomes from blood serum [51]; PEG functionalized iron oxide nanoparticles for exosome purification: (c) principle and (d) exosome quantification before and after purification and SDS-PAGE gel of purified exosomes [20].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/molecules26041135

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!