The rapid emergence of resistance in plant pathogens to the limited number of chemical classes of fungicides challenges sustainability and profitability of crop production worldwide. Under-standing mechanisms underlying fungicide resistance facilitates monitoring of resistant popula-tions at large-scale, and can guide and accelerate the development of novel fungicides.

- fungicide resistance

- molecular basis

- non-target site

- plant pathogens

Note: The following contents are extract from your paper. The entry will be online only after author check and submit it.

1. Introduction

Fungicide use is a major component in the integrated disease management for crop production, especially in open fields. The estimated amount of fungicides and bactericides used worldwide increased from 393 to 530 million kilograms during 1990 to 2018 (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; http://www.fao.org/). Despite the availability of a wide variety of fungicides, control of major diseases heavily relies on only a few chemical classes due to efficacy or residue concerns [1,2], leading to a high pressure of resistance selection. Fungal pathogens hitchhiking on goods or latently infected in plants can easily be distributed between regions and countries, further challenging the resistance management. The rate of emergence of resistant fungal populations has been continuously rising globally since the 1980s, posing a serious threat to farming sustainability and profitability [3]. One way to cope with fungicide resistance is through fundamental understanding of its mechanisms, which can facilitate resistance monitoring and aid in the development of novel fungicides.

Numerous studies have been conducted in the past to characterize modes of action of fungicides and corresponding resistance mechanisms. Fungicides, in particular those with single sites of action, function to block specific enzymes in critical biological pathways. Thus, the change either in the structure or the expression level of the enzyme can largely affect fungicide efficacy. These target site-based resistance mechanisms have been found in many fungi with resistance to various fungicides belonging to different chemical classes [4]. While the structural change of target sites is typically due to mutations in residues involved in the binding site, overexpression of the target sites oftentimes results from the rearrangement or mutations in its promoter region [4–6]. In either case, the resistance is considered to be linked to a single genetic locus and heritable, and is named qualitative resistance. The level of resistance is largely determined by specific mutations or the expression level of a given target site [5,7]. In contrast, resistance can also be attributed to other factors or mutations in multiple loci, termed quantitative resistance [8]. In addition, other terms such as innate or natural resistance and epigenetic resistance are used to describe certain fungal species that are insensitive to a given fungicide and transient resistance mediated by gene regulation, respectively [9,10]. However, some of these alternative mechanisms of resistance have not been well studied, although field-resistant isolates that lacked mutations or had similar expression levels of target sites compared to sensitive isolates have been reported across pathosystems [9,11–14].

2. Resistance mediated by drug efflux transporters

Many studies have shown associations between enhanced activity of efflux transporters and emergence of resistance in a wide range of fungal pathogens [15–18], indicating efflux transporters may have a common and critical role in fungicide sensitivity. In addition, simultaneous resistance to multiple chemical classes of fungicides was found to be attributable to overexpression of efflux pumps in some important fungal pathogens. In this section, the general role of drug efflux transporters and the key members that have been linked to fungicide resistance were reviewed.

2.1. Drug Efflux Transporter in Fungi

In all living organisms, drug efflux transporters are integral membrane-bound proteins that transport a wide range of substrates, such as protein macromolecules, ions, or small molecules across a biological membrane [19]. Thus, they can mediate the efflux of a variety of toxic substrates from the cell, preventing toxin accumulation. In fungi, toxins can be self-produced or come from the environment. Synthetic fungicides are typically regarded as toxins to fungal populations, of which the efficacy can therefore be affected by the activity of drug efflux transporter. Two major groups of drug transporters have been characterized in fungi, including ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters and major facilitator superfamily (MFS) transporters.

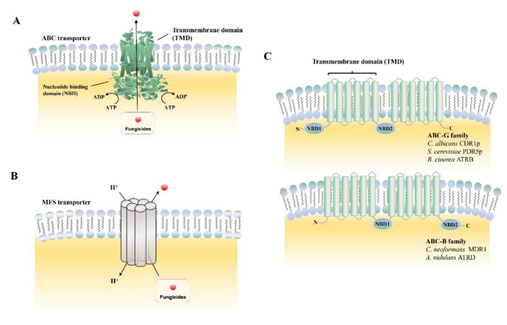

The ABC superfamily is the dominant drug transporter, consisting of a transmembrane domain (TMDs) and a structurally conserved nucleotide-binding domain (NBDs) (Figure 1A,C). One important property of ABC transporters is their low substrate specificity, which allows them to transport a variety of structurally different compounds [20]. Based on the “architectures” of the protein, the ABC transporters were grouped into seven sub families (A–G). Unlike ABC transporters that export toxic compounds by tight coupling of ATP cleavage, the MFS transporters transfer compounds by the proton-motive force across the fungal plasma membrane (Figure 1B). In total, the MFS transporters contain 74 families, with each usually responsible for a specific substrate type [21]. Table 1 lists the ABC and MFS transporters currently identified in phytopathogenic fungi. The known functions of MFS transporters include drug efflux systems, transfer endogenously produced toxins, metabolites of the Krebs cycle, organophosphate/phosphate exchangers, and bacterial aromatic permeases [19].

Figure 1. Biological structures of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) and major facilitator superfamily (MFS) transporters. (A) Domain arrangements of ABC transporters in the plane of the membrane; (B) working model of MFS transporter in the plane of the membrane; (C) schematic of “normal” arrangement of transmembrane domain (TMD), nucleotide-binding domain (NBD): Example of the ABC-G and ABC-B families.

Table 1. ABC and MFS transporters identified in plant pathogenic fungia.

|

Species |

Host |

Protein |

Group |

Function |

Fungicide substrate |

Reference |

|

Fusarium culmorum |

Cereals |

FcABC1 |

ABC-G |

Virulence, fungicide sensitivity |

DMIs |

[22,23] |

|

Fusarium graminearum |

Wheat |

FgABCC9 |

ABC-C |

Fungicide sensitivity; growth and pathogenicity |

DMIs |

[24] |

|

F. graminearum |

Wheat |

FgARB1 |

ABC-F |

Penetration; infection; growth |

n.d. |

[25] |

|

F. graminearum |

Wheat |

FgABC1 |

ABC-C |

Secretion of fungal secondary metabolites |

n.d. |

[26] |

|

F. graminearum |

Wheat |

FgABC3 |

ABC-G |

Virulence, fungicide sensitivity |

DMIs |

[26] |

|

F. graminearum |

Wheat |

FgATM1 |

ABC-B |

Iron homeostasis |

n.d. |

[27] |

|

F. graminearum |

Wheat |

FgABC1 (FGSG_04580) |

ABC-G |

Virulence |

n.d. |

[28] |

|

Fusarium sambucinum |

Potato |

GpABC1 |

ABC-G |

Virulence |

n.d. |

[29] |

|

Nectria haematococca |

Pea |

NhABC1 |

ABC-G |

Virulence |

n.d. |

[30] |

|

Grosmannia clavigera |

Pine trees |

GcABC1 |

ABC-G |

Virulence |

n.d. |

[31] |

|

Magnaporthe oryzae |

Rice |

MoABC1 |

ABC-G |

Pathogenicity |

n.d. |

[32] |

|

M. oryzae |

Rice |

MoABC2 |

ABC-G |

Multidrug sensitivity |

Blasticides, DMIs, antibiotics |

[33] |

|

M. oryzae |

Rice |

MoABC3 |

ABC-B |

Infection structure formation |

n.d. |

[34] |

|

M. oryzae |

Rice |

MoABC4 |

ABC-A |

Pathogenicity |

n.d. |

[35] |

|

M. oryzae |

Rice |

MoABC5 |

ABC-C |

Pathogenicity |

n.d. |

[36] |

|

M. oryzae |

Rice |

MoABC6 |

ABC-C |

Hyphal growth |

n.d. |

[36] |

|

M. oryzae |

Rice |

MoABC7 |

ABC-C |

Conidiation |

n.d. |

[36] |

|

Botrytis cinerea |

Fruits, vegetables |

BcATRA |

ABC-G |

Multidrug transporter |

Cycloheximide, catechol |

[37] |

|

B. cinerea |

Fruits, vegetables |

BcATRB |

ABC-G |

Multidrug sensitivity |

PPs, MBCs, APs, tolnaftate |

[15] |

|

B. cinerea |

Fruits, vegetables |

BcMFSM2 |

MFS |

Multidrug sensitivity

|

Dicarboximides, SDHIs, tolnaftate, APs, PPs, KRIs, DMIs, cycloheximide |

[15] |

|

B. cinerea |

Fruits, vegetables |

BcMFS1 |

MFS |

Multidrug sensitivity

|

DMIs |

[38] |

|

B. cinerea |

Fruits, vegetables |

BcATRD |

ABC-G |

Fungicides sensitivity |

DMIs |

[39] |

|

Sclerotinia homoeocarpa |

Turf grass |

ShATRD |

ABC-G |

Fungicides sensitivity |

DMIs |

[40] |

|

Penicillium digitatum |

Citrus |

PMR1 |

ABC-G |

Fungicides sensitivity |

Azole |

[41] |

|

P. digitatum |

Citrus |

PMR5 |

ABC-G |

Multidrug sensitivity

|

MBCs, quinone, resveratrol, camptothecin |

[17] |

|

P. digitatum |

Citrus |

PdMFS1 |

MFS |

Fungicides sensitivity; virulence |

DMIs |

[18] |

|

Zymoseptoria tritici |

Wheat |

MgATR1 |

ABC-G |

Transportation of various chemicals |

DMIs |

[42] |

|

Z. tritici |

Wheat |

MgATR2 |

ABC-G |

Transportation of various chemicals |

DMIs |

[42] |

|

Z. tritici |

Wheat |

MgATR4 |

ABC-G |

Virulence factor that affects colonization, fungicides sensitivity |

DMIs |

[43] |

|

Z. tritici |

Wheat |

MgATR7 |

ABC-G |

Iron homeostasis |

n.d. |

[44] |

|

Clonostachys rosea |

Soil-borne saprotroph |

CrABCG29 |

ABC-G |

H2O2 tolerance |

n.d. |

[45] |

|

Colletotrichum gloeosporioides |

Apple |

CgABCF2 |

ABC-F |

Asexual and sexual development; appressorial formation; plant infection |

n.d. |

[46] |

|

Colletotrichum higginsianum |

Arabidopsis thaliana |

ChMFS1 |

MFS |

Hyphal morphology; conidiation; pathogenicity |

n.d. |

[47] |

|

Colletotrichum acutatum |

Hot pepper |

CaABC1 |

ABC-G |

Conidiation; abiotic stress; multidrug sensitivity |

Phosphorothiolates, QoIs, MBCs |

[48] |

|

Gibberella pulicaris |

Potato |

GpABC1 |

ABC-G |

Virulence |

n.d. |

[29] |

|

Alternaria alternata |

Citrus |

AaMFS19 |

MFS |

Cellular resistance to oxidative stress and fungicides |

Clotrimazole, PPs, inorganics |

[49] |

|

Cercospora nicotianae |

Tobacco |

CTB4 |

MFS |

Virulence |

n.d. |

[50] |

|

Monilinia fructicola |

Peach |

MfABC1 |

ABC-G |

Fungicides sensitivity |

DMIs |

[51] |

a According to previous publications. DMIs: Demethylation inhibitors; MBCs: Methyl benzimidazole carbamates; APs: Anilino-pyrimidines; PPs: Phenylpyrroles; QoIs: Quinone outside inhibitors; KRIs: Ketoreductase inhibitors; SDHIs: Succinate dehydrogenase inhibitors; n.d.: Not determined.

2.2. ABC/MFS Genes in Plant Pathogenic Fungi

Overall, ascomycetes, zygomycetes, and basidiomycetes tend to have a significantly smaller number of ABC superfamily proteins and MFS transporters, compared to oomycetes and ancient Chytridiomycota [52]. In ascomycetes, approximately 40 to 50 ABC transporters and over 200 MFS transporters have been revealed, with 100 MFS transporters more or less belonging to the multidrug resistance (MDR) proteins [16,52,53]. For example, 50, 44, and 54 genes were predicted to be ABC transporters in Magnaporthe oryzae, Botrytis cinerea, and Fusarium spp., respectively [26,52,54]. A total of 229 putative MFS transporter genes and 44 putative ABC transporter genes were identified from the Zymoseptoria tritici IPO323 genome database available at the JGI database (www.jgi.doe.gov) [55].

Some ABC transporters have been functionally characterized from plant pathogenic fungi (Table 1), yet the role of most remains unknown. Studies of ABC transporters in plant pathogens are often focused on their involvement in the development of multi-fungicide resistance, such as the BcATRB and the BcATRD in B. cinerea [39,56], and the PMR1 and PMR5 in Penicillium digitatum [17,57]. In addition, some ABC transporters have been associated with plant pathogenesis, presumably due to the export of plant defense compounds [58] (Table 1). With regard to MFS transporters, they are generally less understood compared with ABC transporters. The constitutive overexpression of MFS genes in several fungi have been shown to cause MDR phenotypes, including the MgMFS1 in Z. tritici [16], the PdMFS1 in P. digitatum [18], and the BcMFSM2 in B. cinerea [15]. The deficiency of some MFS transporters was found to be linked with increased sensitivity to a variety of chemicals, confirming their roles in MDR. Similarly, MFSs in plant pathogens can secrete host-specific toxins, affecting plant pathogenesis [52] (Table 1).

2.3. Efflux Transporter-Mediated Mechanisms of Fungicides Resistance

In phytopathogenic fungi, the first MDR phenotype was described in P. digitatum isolates from lemon fruit, which showed resistance to DMI fungicides including triflumizole, fenarimol, bitertanol, and pyrifenox [41]. Thereafter, field-relevant resistance to multiple chemical classes of fungicides were found in isolates of Z. tritici [16], B. cinerea [15], Oculimacula yallundae [59], Sclerotinia homoeocarpa [40], and Penicillium expansum [60]. Although exact mechanism(s) of MDR remained unknown in some pathogens (e.g., O. yallundae), it was typically caused by the overexpression of certain efflux transporters.

2.3.1. Expression of Efflux Transporters

The majority of efflux transporters are silent or weakly expressed in the absence of toxic compounds, but their expressions can be rapidly induced by the addition of those drugs or phytoalexins [8]. Further, fungal sensitivity to antifungal agents could increase significantly without functional efflux transporters [61]. Although the expression of efflux transporters could be induced in as short as 10 to 15 minutes, this “lag period” seems to be sufficient for toxins to diffuse into fungal cells, leading to growth inhibition. However, if the transporters regulating fungal sensitivity are expressed constitutively, the drug uptake would be blocked and the resistance is thus conferred [20].

The constitutive overexpression of ABC transporter BcATRB and MFS transporter BcMFSM2 causing MDR phenotypes has been discovered in B. cinerea. Specifically, overexpression of BcATRB was found to confer resistance to fludioxonil, carbendazim, cyprodinil, and tolnaftate, and the associated phenotype was termed MDR1, whereas the phenotype displaying resistance to iprodione, boscalid, tolnaftate, cyprodinil, fludioxonil, fenhexamid, tebuconazole, bitertanol, and cycloheximide, caused by overexpression of BcMFSM2, was defined as MDR2 [15]. In addition, the natural hybridization of MDR1 and MDR2 was also revealed, designated as the MDR3 phenotype, which showed a combined resistance profile of MDR1 and MDR2 phenotypes [15]. Later on, a stronger MDR1 phenotype strain, MDR1h, with a higher expression level of the BcATRB was found to have more resistance to fludioxonil and cyprodinil than the MDR1 strains [62]. In Z. tritici, the causal agent of Septoria leaf blotch on wheat, overexpression of the major facilitator gene MgMFS1 was linked to strong resistance towards DMIs, and weak resistance towards QoIs and SDHIs [63,64]. Disruption of the Mgmfs1 gene increased its sensitivity to several chemicals, including tolnaftate, epoxiconazole, boscalid [16], several QoIs, and an unrelated compound cercosporin [65]. In P. digitatum, overexpression of PMR1, PdMFS1, and PdMFS2 was correlated with complete or partial resistance to triflumizole [41], imazalil [66], and prochloraz [67]. In S. homoeocarpa, reduced propiconazole sensitivity was identified from five New England sites during a 2-year field efficacy study, with the EC50 values greater than 50-fold compared with those of the sensitive isolates. The overexpression of the PDR (pleiotropic drug resistance) transporter ShATRD was found to be strongly correlated with practical field resistance to propiconazole via transcriptomic and molecular analyses. Overexpression of the target gene of DMIs, ShCYP51b, only presents a minor factor affecting the sensitivity [40]. In addition to ShATRD, the overexpression of ShPDR1 is also correlated with practical field resistance to DMI fungicide propiconazole and reduced sensitivity to dicarboximide iprodione and SDHI fungicide boscalid [68].

2.3.2. Modulator

Compounds able to modulate the activity of ABC or MFS transporters may reverse MDR, due to their inhibitory activity towards drug efflux from cells. Such compounds are usually called “modulators” or “inhibitors”. Among them, some modulators have been tested for their activity in plant pathogenic fungi. For B. cinerea, the phenothiazine chlorpromazine and the macrolide tacrolimus have modulator activity towards oxpoconazole [69]. In MDR2 and/or MDR3 isolates, synergism was found between modulator verapamil and tolnaftate, fenhexamid, fludioxonil, or pyrimethanil, suggesting that verapamil may inhibit the MFS transporter BcMFSM2 [70]. Similar inhibitory activity of verapamil, amitriptyline, and chlorpromazine toward the efflux was also observed in Z. tritici displaying MDR phenotype [16]. Whether modulators could be implemented for improving fungicide efficacy under field conditions needs to be further investigated.

2.4. Genetic Factors underlying Overexpression of Efflux Pumps

2.4.1. Transcription Factors

Two different mechanisms have been attributed to the overexpression of efflux pumps that are responsible for fungicide resistance. The most common one is amino acid changes in certain transcription factors that escalate expression levels of efflux pumps. As noted above, all B. cinerea isolates with MDR1 phenotype possessed point mutations in the MRR1, a transcriptional factor of BcATRB [15]. The mutations transform the transcription factors from a drug-inducible state to a permanently active state, resulting in the overexpression of an ABC transporter BcATRB. Transformation of the MDR1-type MRR1 confirmed that those point mutations are responsible for permanent activation of MRR1 and overexpression of BcATRB [15]. Furthermore, in MDR1h isolates, a deletion of 3-bp resulting in loss of amino acid (L497) in MRR1 caused overexpression of BcATRB than MDR1 isolates. In S. homoeocarpa, a gain-of-function mutation (M853T) in the activation domain of ShXDR1 renders constitutive overexpression of ABC transporters (ShPDR1 and ShATRD) and several CYP450 genes (CYP561, CYP65, CYP68), leading to the MDR phenotype [71]. However, expression of ATRB or other ABCs may not be exclusively regulated by a single transcription factor (e.g., MRR1) [72].

Interestingly, both MRR1 and ShXDR1 contain a Zn2Cys6 domain. Similarly, Wang et al. showed that MoIRR encoding a Zn2Cys6 transcription factor is associated with resistance in M. oryzae to isoprothiolane, a dithiolane fungicide used for rice blast control [73]. Mutations including R343W, R345C, and a 16-bp insertion in MoIRR were found in three lab mutants of M. oryzae with a moderate level of isoprothiolane resistance. In addition, cross-resistance with iprobenfos was observed, indicating that MoIRR may pay a significant role in resistance to choline biosynthesis inhibitors [73]. However, whether MoIRR regulates efflux pump(s) and whether those mutations may lead to differential expressions of other genes in the same mutants is largely unknown [74]. Transcription factors or activators containing fungal-specific Zn2-Cys6 DNA-binding domain were also found to contribute to DMI fungicide resistance in Rhynchosporium commune [75]. Apart from Zn2Cys6, leucine zipper transcription factors CaBEN1 and YAP 1, and zinc finger CRZ 1 have been involved in resistance or reduced sensitivity to benomyl in Colletotrichum acutatum [76], to several fungicide groups (i.e., clotrimazole, fludioxonil, vinclozolin, and iprodione) in Alternaria alternata [77], and to DMIs in P. digitatum [78], respectively. Collectively, these examples suggest that transcription factors may play a critical role in mediating fungicide resistance via regulating drug efflux pumps in most cases.

2.4.2. Promoter Rearrangement

The insertion in the promoter region of an efflux transporter has also been reported to cause MDR. In B. cinerea, two types of rearrangements in the promoter region of BcMFSM2 were correlated with multidrug resistance. In the type A rearrangement, the BcMFSM2 promoter contained a 1326-bp insertion in conjunction with a 678-bp deletion. The type B rearrangement contained a 1011-bp insertion and a 76-bp deletion [79]. The MDR2 and MDR3 strains with the type A insertion occurred in the French (in Medoc, Champagne, Alsace regions), and German Wine Road regions, while the type B insertion was only found in the champagne region of France. MDR2 isolates harboring either the type A or type B rearrangement showed the same resistance phenotypes, with similar levels of BcMFSM2 overexpression [79]. Constitutive activation of the BcMFSM2 promoter by the rearrangement was confirmed by using reporter gene fusions [15]. Similarly, three different types of insertion (types I, II, or III, depending on the length of the insertion in the MFS1 promoter) have been reported to be present in the promoter region of the MgMFS1 promoter in Z. tritici. Through gene replacement, the insertions were verified to be responsible for MgMFS1 overexpression and the MDR phenotype [64]. The type I insertion was a long terminal repeat (LTR)-retrotransposon that could drive MgMFS1 expression by itself, as LTR elements typically contain cis-regulatory sequences. The type II insertion also possess similar upstream activation sequences (UASs), while the type III insert seemed devoid of regulatory elements. All those insertions resulted in the overexpression of MgMFS1, and thus cause MDR [64].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/microorganisms9030502