Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) is inherited in a predominantly autosomal recessive manner with over 45 currently identified causative genes. It is a clinically heterogeneous disorder that results in a chronic wet cough and drainage from the paranasal sinuses, chronic otitis media with hearing impairment as well as male infertility. Approximately 50% of patients have situs inversus totalis. Prior to the development of chronic oto-sino-pulmonary symptoms, neonatal respiratory distress occurs in more than 80% of patients as a result of impaired mucociliary clearance and mucus impaction causing atelectasis and lobar collapse. Diagnosis is often delayed due to overlapping symptoms with other causes of neonatal respiratory distress. A work up for PCD should be initiated in the newborn with compatible clinical features, especially those with respiratory distress, consistent radiographic findings or persistent oxygen requirement and/or organ laterality defects

- primary ciliary dyskinesia

- neonatal respiratory distress

1. Neonatal Respiratory Distress

Respiratory distress develops in about 7% of all newborn infant deliveries [1]. Respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) develops in 1% of all newborn infant deliveries primarily in premature babies due to surfactant deficiency, and its prevalence is inversely associated with gestational age. More than 50% of infants born at <28 weeks’ gestation develop RDS compared to <5% of those greater than 37 weeks gestation. In 2014, nearly 10 of every 100 infants were delivered at <37 completed weeks’ gestation. Neonatal RDS contributes to significant morbidity and mortality and is ranked in the top 10 leading causes of infant mortality. It is the leading cause of mortality in premature infants and contributes to 2% of all causes of infant deaths [2].

Clinical symptoms of respiratory distress in neonates include tachypnea, nasal flaring, grunting, retractions and cyanosis. The differential diagnosis for neonatal respiratory distress is broad and includes RDS, transient tachypnoea of the newborn (TTN), neonatal pneumonia, pulmonary air leak such as pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum, pulmonary arterial hypertension, congenital heart disease, interstitial lung diseases such as those due to surfactant protein deficiencies and other non-pulmonary systemic disorders such as neonatal sepsis, hypothermia and metabolic acidosis. Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) presents with neonatal respiratory distress in majority of patients and should be considered in the differential diagnosis, especially in term infants with respiratory distress. Given the long-term complications related to chronic airway inflammation and infection, making the diagnosis in the neonatal period is critical.

2. Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia

| Organ | Clinical Feature |

|---|---|

| Ears | Recurrent otitis media Chronic otitis media Suppurative otitis media Hearing impairment |

| Nose and sinuses | Early onset, year-round nasal congestion Chronic or recurrent sinusitis Nasal polyps |

| Lower respiratory tract | Unexplained neonatal respiratory distress Atelectasis and lobar collapse Early onset, year-round chronic cough Recurrent pneumonia Bronchiectasis |

| Cardiac | Heterotaxy (situs ambiguus or another organ laterality defect other than situs inversus totalis) Situs inversus totalis Congenital heart disease |

| Reproductive organs | Male infertility Reduced female fertility |

3. Respiratory Distress in the Newborn with Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia

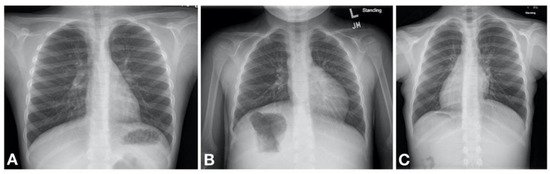

Primary ciliary dyskinesia typically causes respiratory distress in the neonate with more than 80% of patients presenting with symptoms within the first 1–2 days of life [19,23,24,25,26,27]. It is thought that the impaired mucociliary clearance in the newborn results in atelectasis and lobar collapse due to mucus impaction which are notable on chest radiography in neonates with PCD developing respiratory distress [23]. These initial clinical manifestations are often transient, although some patients may have persistent oxygen requirement lasting weeks to months. Gradually a daily wet cough as well as nasal congestion with drainage become noticeable [19]. It is therefore likely that the initial transient nature of the symptoms poses a missed opportunity for diagnosis due to a low index of suspicion for PCD to initiate a workup. Some helpful distinguishing features between PCD and other causes of neonatal respiratory distress include the following. First, there is a somewhat later onset of symptoms; infants with PCD may not develop respiratory distress until 12–24 h after birth [23]. Second, the patient is typically a term infant without other obvious risk factors for respiratory distress. Third, the chest imaging often shows lobar atelectasis, rather than diffuse changes characteristic of, for example, TTN; although this is not universal. Fourth, many PCD patients have situs inversus totalis (approximately 50% of patients) [18] or other forms of heterotaxy (12% of patients). Therefore, a work up for PCD should be concurrently initiated in the neonate with respiratory distress especially in those with compatible clinical and/or radiological features.

4. Diagnosis of Primary Ciliary Dyskinesia

In spite of unexplained neonatal respiratory distress in more than 80% of neonates with PCD [23] the diagnosis of PCD is often delayed [16]. Varying ciliary structure and function results in varying times of manifestation of the classic PCD phenotype [8] and may contribute to the delay in diagnosis. There is not a “Gold standard” diagnostic test for PCD and a panel of diagnostic tests is therefore recommended to support the diagnosis with a greater number of positive tests resulting in a higher likelihood of having PCD in those meeting clinical criteria [8]. It is important to note that several similarities and differences exist between the recommended tests per the guidelines put forth by the European respiratory society (ERS) in 2017 [28] and the American thoracic society (ATS) in 2018 [29]. These differences are clearly elucidated in an editorial by Shoemark et al. [30] These tests include; (1) PCD genetic test panels; and (2) ciliary biopsy or brush biopsy culture with TEM. Note that immunofluorescence techniques are available in many European centers and will likely become, increasingly, a useful tool in the neonate. For older patients (over five years) nasal nitric oxide measurement can be successfully completed, but this is not suitable for use in newborns (3) additional tests not currently recommended in the ATS diagnostic panel include cytologic analysis or ciliary motion, which can be falsely negative [29]. These tests are, however, recommended by the ERS when used in conjunction with other PCD tests.

The suggested criteria for the diagnosis of PCD by age are summarized in the 2016 PCD foundation consensus statement [8]. Note that the utility of some of the diagnostic tests are further clarified in the 2018 guidelines [29]. After excluding other diseases with overlapping clinical symptoms, the major criteria include;

-

Unexplained neonatal respiratory distress (at term birth) with lobar collapse and/or need for respiratory support with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) and/or oxygen for >24 h.

-

Any organ laterality defect—situs inversus totalis, situs ambiguous, or heterotaxy.

-

Daily, year-round wet cough starting in first year of life or bronchiectasis on chest CT.

-

Daily, year-round nasal congestion starting in first year of life or pansinusitis on sinus CT.

Leigh et al. reported a specificity for diagnosis of PCD in early childhood of greater than 96% in patients presenting with a combination 3 or more of the major criteria [26]. In the neonatal period, a diagnosis of PCD can be made based on a combination of unexplained respiratory distress in a term birth and any organ laterality defect (including situs inversus totalis, situs ambiguous or heterotaxy) plus at least a diagnostic ciliary ultrastructure on TEM or presence of biallelic mutations in one PCD-associated gene [8]. High speed video microscopy or ciliary beat frequency or waveform analysis are no longer suggested initial diagnostic tests by the ATS [29]. Similarly, based on the ERS guidelines, a positive diagnosis can be made if there is presence of a hallmark ciliary ultrastructure defect on TEM plus non-ambiguous bi-allelic mutations in PCD causing genes.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/children8020153