In 2021, the 100th anniversary of the isolation of insulin and the rescue of a child with type 1 diabetes from death will be marked. In this review, we highlight advances since the ingenious work of the four discoverers, Frederick Grant Banting, John James Rickard Macleod, James Bertram Collip and Charles Herbert Best. Macleoad closed his Nobel Lecture speech by raising the question of the mechanism of insulin action in the body. This challenge attracted many investigators, and the question remained unanswered until the third part of the 20th century. We summarize what has been learned, from the discovery of cell surface receptors, insulin action, and clearance, to network and precision medicine

- insulin

- hundredth anniversary

1. Introduction

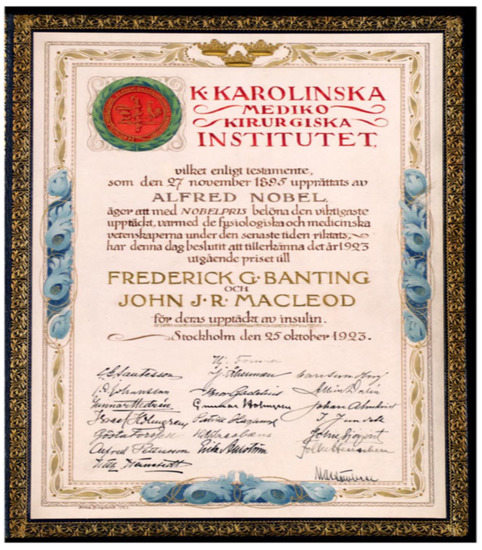

The purification of insulin by the Toronto “Fab Four”, leading to the rescue of humans dying from diabetes, is one of the most dramatic examples of translational research, providing inspiration for us all. Banting, a practicing surgeon in Toronto, was inspired in October 1920 by reading an article related to pancreatic lithiasis, the islets of Langerhans and diabetes [1], and he explained his idea to Macleod in November 1920. After reviewing the experimental protocol and bypassing the pancreatic duct ligation step to preserve the islets, they started experiments with a student, Charles Best, in Macleod’s lab in May 1921. After several wrong turns, they invited Collip, a young professor from the University of Alberta on sabbatical leave in the laboratory of Macleod, who brought with him a new technique called chromatography, to join the group. Within weeks, Collip and Best developed a robust purification protocol to purify insulin from crude extracts. They successfully delivered purified insulin to the first patient, Leonard Thompson, on 23 January 1922, 15 months after the initial idea and 8 months from the onset of experiments [2,3,4,5]. They were awarded the Nobel Prize in October 1923 (Figure 1). In medical research, the ultimate goal is to have a practical application introduced rapidly after the relevant basic science discovery. Albeit unachievable now—that was translation!

Figure 1. The Nobel Prize certificate to Banting and Macleod signed by the 21 members of the[1][2] Nobel Prize committee. From the Nobel Foundation. In his 1925 Nobel Lecture, Macleod closed by raising the question—what is the mechanism of insulin action in the body[3][4][5][6][7][8][9]

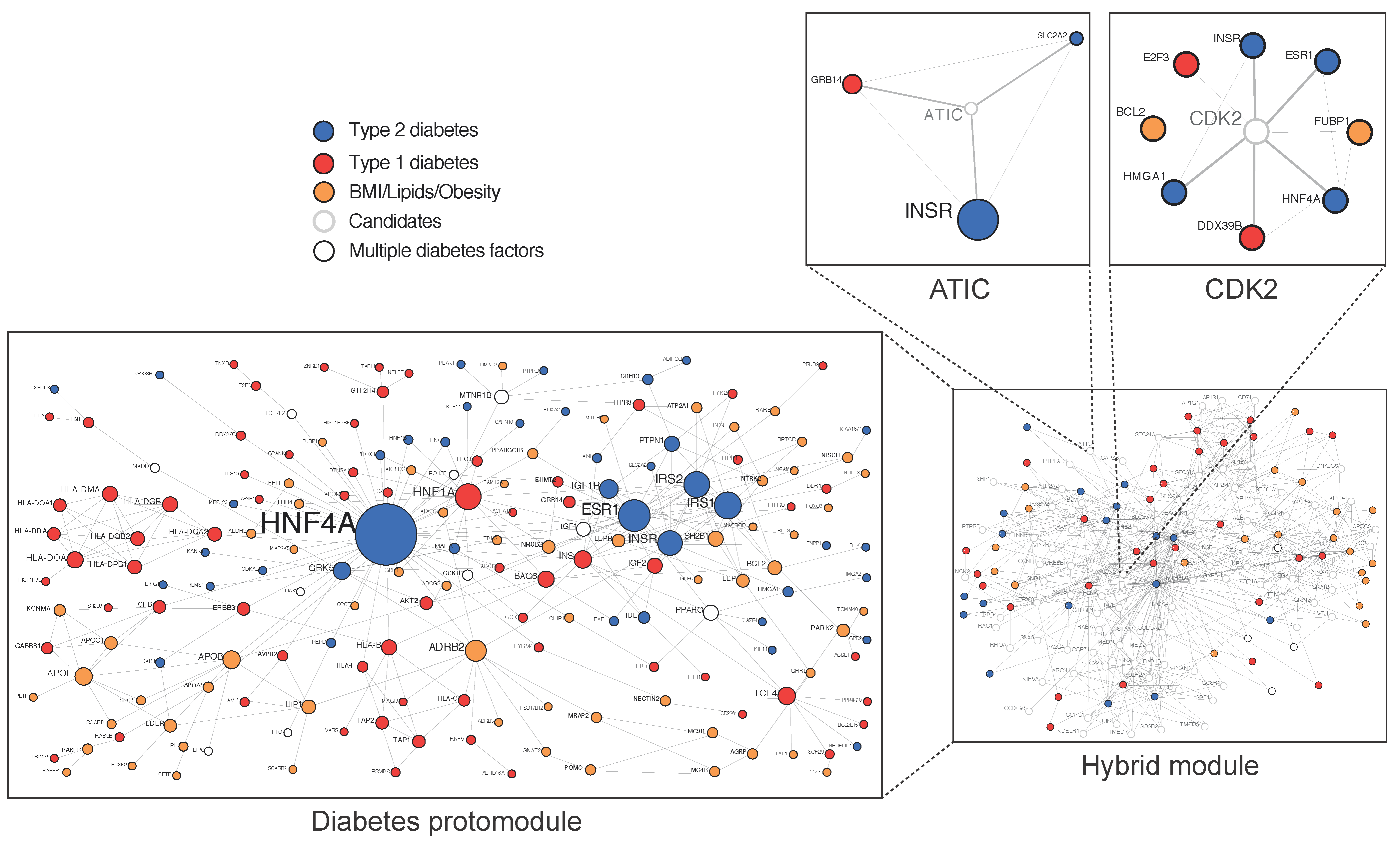

Approximately 40% of the variance in T2D is due to genetics [11,12], with an association between parental history deriving from inherited traits but also environmental factors [13]. The genetic analysis of large cohorts, mainly originating from genome wide association (GWAS) data, complemented by analyses of exome- and genome sequence data, has raised questions concerning the “missing heritability” and the biological space occupied by numerous common variants, with a small causality dispersed throughout the human genome and many of them located in regulatory intronic areas [14,15,16,17].Because all cellular processes involve scale-free networks, their study at a network level has been an important recent focus in cell biology and medicine and can be used to understand the genotype/phenotype relationship [18,19,20]. In 2007, the first diseasome constructed by the mathematician Albert Barabasi from the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man database (OMIM) showed that T2D occupies a central hub [21]. In 2018, the first T2D physical protein–protein interactions network (PPIN), constructed from validated variants, termed diabetes protomodule, displayed the proteins’ hepatic nuclear factors HNF4A and HNF1A as central nodes [22] (Figure 2). The HNF1A variant identified by whole-exome sequencing in a homogeneous Latino cohort is an example of a rare variant with a high causality at a population level [23].

Figure 2. Diabetes-associated genes form a protomodule. 184 genes at risk of T2D are here validated in a single component proteins–proteins interaction network of 309 iterations called protomodule. (Adapted from Boutchueng et al. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205180).

2. The Insulin Receptor-Tyrosine Kinase (IR)

Macleod closed his Nobel Lecture speech by referring to the “perplexing problem of the mechanism of insulin action in the body” [24]. The answer was provided 50 years later. Instead of asking “what is the mechanism of insulin action?” the advent of radio-assays allowed researchers to ask the question, “how does the cell know that insulin is there?” The concept of cell surface receptors having the capacity to detect a faint signal in a high background was introduced [25]. Insulin without its receptor cannot perform any functions [26]. Soon after the discovery of tyrosine phosphorylation [27], it was demonstrated that the mature IR is a tyrosine kinase [28,29,30]. The Kadowaki variants, which are located in the IR tyrosine kinase domain and have resulted in severe insulin resistance in a child with Leprechaunism syndrome [31], are examples of rare variants with a high causality. The structure of the mature, full-length IR in complex with insulin was recently resolved by cryo-electron microscopy and allowed for a revision of the IR activation model [32]. Notably, following the binding of two insulin molecules to the inversed V-shaped extracellular alpha-subunits, two hinge motions were confirmed. The first one involves a large conformational change between the cysteine rich (CR) and leucin rich-2 (L2) domains, where the loop that connects the two domains acts as the hinge. The second one occurs around the linker between the L2 and fibronectin (FnIII-1) domains, resulting in a new interdomain interaction between specific residues of L2 and FnIII-1. The combination of these two hinge motions makes each of the IR promoters adopt an inverted “J” shape. Two J-shaped promoters constitute the “T”-shape active tetrameric IR. Following the formation of the T-shaped IR, the membrane-proximal regions of the two IR promoters are brought together by an interaction between the two FnIII-2 domains. These large mechanical movements, similar to the epidermal growth factor (EGF)receptor model, promote the transmembrane TM–TM interaction and enable the trans-autophosphorylation of the intracellular tyrosine kinase domains, leading to the active IR [32]. Of further interest, the IR seems to have two different conformations at low and saturating insulin concentrations, promoting different activities and suggesting that the IR may act as a sensor of circulating insulin concentration. The different conformational states induced by low or high levels of circulating insulin would generate various signaling outputs (metabolic versus mitogenic responses), implying that insulin levels should be finely regulated. With a single conformational change (two insulin versus four molecules bound by a receptor), the IR can generate a regulated response, and the local membrane microenvironment seems to also be important [33,34]. The IR has two isoforms (IR-B and IR-A) [35]. The vast majority of studies involved in the mechanisms of regulation of endocytosis and sorting of the receptor were performed before the identification of the IR-A isoform, and mostly in adipocytes, which preferentially express the IR-B isoform [36].

3. IR Endocytosis and Insulin Clearance

Following insulin binding on the cell surface of hepatocytes, the IR insulin complexes are internalized and insulin is degraded [37]. Najjar and colleagues identified the molecular mechanisms by which CEACAM1 regulates insulin internalization and degradation through the IR-A isoform in the liver [38,39,40]. On the other hand, Mirsky and Broh-Kahn first described the existence of an insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE) that inactivated insulin in rat tissue extracts from the liver [41]. Roth and colleagues purified to homogeneity this protease, characterizing its biochemical properties and identifying that insulin can bind to IDE [42,43]. Duckworth and colleagues identified a peptide bonds cleavage by IDE in vitro and in cultured cells and postulated a model in which IDE played a major role for cellular handling and the degradation of insulin [44,45].

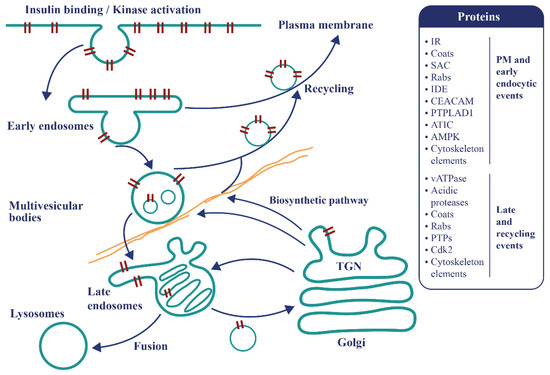

Endosomal apparatus is a topologically versatile tubulo-vesicular compartment controlling signaling events and metabolism [46,47] (Figure 3). Recent findings promote a re-examination of the mechanisms of IR endocytosis and its relationship with insulin resistance, as well as clearance and its connection with pancreatic secretion. A specific internalization pathway involving subunits of the mitotic check point complex (MCC) was described [48]. After insulin stimulations, the mitosis arrest deficiency 2 (MAD2) and budding uninhibited by benomyl 1-related 1 (BUBR1), as well as the clathrin adaptor protein AP2, assemble at the IR-beta subunit, triggering the internalization of the active IR complexes and stopping insulin signaling at the plasma membrane [48]. The MAD2-binding protein p31comet (P31comet) prevents the conformational activation of MAD2 and plays a critical role in insulin signaling. MAD2 directly binds to the C-terminal MAD2 interacting motif (MIM) of the IR and recruits AP2 to IR through BUBR1. P31comet prevents IR endocytosis by blocking the interaction of BUBR1-AP2 with IR-bound MAD2. Adult liver-specific P31comet knock out mice exhibit premature IR endocytosis in the liver and whole-body insulin resistance [49]. Conversely, BUBR1 deficiency delays IR endocytosis and enhances insulin sensitivity in mice, and a reduction of IR on the cell surface in liver samples of T2D patients was reported [50]. In addition to MAD2, BUBR1, and P31comet, it was shown that a cell division cycle of 20 proteins (cdc20) is required for IR endocytosis. Feedback regulation of IR endocytosis through a regulation switch on an insulin receptor substrate 1/2 (IRS½) that is dependent on a SH2 domain-containing protein tyrosine phosphatase (PTP), SHP2, and the MAPK pathway was identified. In addition to the MIM motif, the IR juxta-membrane Y960 motif, required to bind IRS1/2, in turn recruits AP2 through YXX Φ motifs collaborating with the MAD2-cdc20-BUBR1 module and leading to efficient formation of the clathrin cage [50]. It was also confirmed that MAD2 disappears from the rat liver plasma membrane within seconds following injections of insulin at fixed time points, further supporting the idea that MCC components, which control the fidelity of chromosome segregation during mitosis, are repurposed in the interphase for early events of IR endocytosis [22]. In addition, there is no concomitant appearance of MAD2 in endosomes, indicating that MAD2 complexes rapidly dissociate as expected for clathrin coats [22]. This supports the view that dysregulation in endocytosis is related to insulin resistance. Of further interest, BUBR1 insufficiency causes premature aging [51,52], raising the question of whether IR might reciprocally act on MCC and spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) signaling during mitosis.

As for the EGFR, IR tyrosine kinase activity appears to be the crucial regulator selecting ligand-dependent movements and signaling in endosomes [53,54,55]. Sorting is achieved with tubulovesicular compartments whose contents are modified by the entry and exits of 70–80 nm vesicles according to the conversion model [56,57]. Proteins involved in these processes have multiple YR-tyrosine phosphorylation regulatory motifs, including Rab5c and vATPase subunits [22]. For example, the lumenal dissociation/degradation sequence of insulin occurring at an acidic pH generated by the proton pumping activity of the vacuolar ATPase (vATPase) would be affected [22]. The liver parenchyma is a major site for insulin clearance, and defects in this process can cause hyperinsulinemia and secondary resistance [58,59,60]. Liver-specific knockout of IR in mice and mice deleted of CEACAM1 develop hyperinsulinemia [60], implying that insulin action and production are essential endosomal responses that limit anabolic processes to nutrient oversupply.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms22031030

References

- Melanie Leroux; Martial Boutchueng-Djidjou; Robert Faure; Insulin’s Discovery: New Insights on Its Hundredth Birthday: From Insulin Action and Clearance to Sweet Networks. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22, 1030, 10.3390/ijms22031030.

- Martial Boutchueng-Djidjou; Pascal Belleau; Nicolas Bilodeau; Suzanne Fortier; Sylvie Bourassa; Arnaud Droit; Sabine Elowe; Robert L. Faure; A type 2 diabetes disease module with a high collective influence for Cdk2 and PTPLAD1 is localized in endosomes. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0205180, 10.1371/journal.pone.0205180.

- Martial Boutchueng-Djidjou; Robert L. Faure; Network medicine-travelling with the insulin receptor: Encounter of the second type.. EClinicalMedicine 2019, 13, 14-20, 10.1016/j.eclinm.2019.07.007.

- Martial Boutchueng-Djidjou; Gabriel Collard-Simard; Suzanne Fortier; Sébastien S. Hébert; Isabelle Kelly; Christian R. Landry; Robert L. Faure; The Last Enzyme of the De Novo Purine Synthesis Pathway 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide Ribonucleotide Formyltransferase/IMP Cyclohydrolase (ATIC) Plays a Central Role in Insulin Signaling and the Golgi/Endosomes Protein Network*. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics 2015, 14, 1079-1092, 10.1074/mcp.m114.047159.

- J. J. R. MacLeod; Insulin and the steps taken to secure an effective preparation. Canadian Medical Association Journal 1922, 12, 899-900, .

- R. L. Noble; Memories of James Bertram Collip.. Canadian Medical Association Journal 1965, 93, 1356-1364, .

- Michael Bliss; Resurrections in Toronto: The Emergence of Insulin. Hormone Research in Paediatrics 2005, 64, 98-102, 10.1159/000087765.

- M Bliss; The eclipse and rehabilitation of JJR Macleod, Scotland’s insulin laureate. Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh 2012, 43, 366-373, 10.4997/jrcpe.2013.401.

- Elliott P. Joslin; The Use of Insulin in its Various Forms in the Treatment of Diabetes*. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 1969, 18, 200-216, .