TGF-β is a powerful inducer of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a differentiation switch that is required for transitory invasiveness of carcinoma cells, the generation of cancer stem cells (CSCs), and phenotypic plasticity, eventually resulting in tumor heterogeneity and resistance to standard chemotherapies.

- autocrine signaling

- cancer

1. Introduction

The transforming growth factor-βs (TGF-βs), TGF-β1, 2 and 3, are secreted polypeptides that signal via two types of membrane serine/threonine kinase receptors, type II (TβRII) and type I (TβRI), and intracellular Smad effectors [1,2,3]. TGF-β1, the most common isoform in human cancers [3], inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in various normal and premalignant human epithelial cells and its essential signaling intermediates, i.e., TβRII and Smad4, are therefore considered tumor suppressors. The anti-oncogenic function of this pathway is supported by the frequent occurrence in cancer cells of genetic and epigenetic alterations that abolish its growth-inhibitory function. In addition, various oncogenes directly hijack the TGF-β/Smad pathway to favor tumor growth. On the other hand, all advanced human tumors overproduce TGF-β, whose autocrine and paracrine actions in most instances promote tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis [3,4]. TGF-β is a powerful inducer of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a differentiation switch that is required for transitory invasiveness of carcinoma cells, the generation of cancer stem cells (CSCs), and phenotypic plasticity, eventually resulting in tumor heterogeneity and resistance to standard chemotherapies [5,6]. Tumor-derived TGF-β acting on stromal fibroblasts generates cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), remodels the tumor stroma and eventually induces expression of mitogenic and survival signals towards the carcinoma cells, while TGF-β acting on endothelial cells and pericytes regulates (neo)angiogenesis [3]. TGF-β also suppresses proliferation and differentiation of lymphocytes, including cytolytic T cells, natural killer cells and macrophages, thus preventing effective eradication of the developing tumor by the host immune system [7]. Hence, TGF-β signaling is intimately involved in nearly all aspects of tumor development [8].

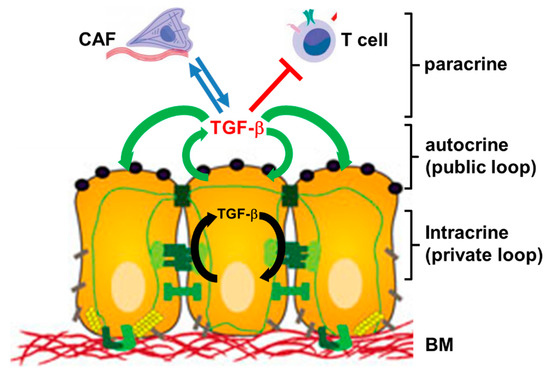

Autocrine signaling is defined as the production and secretion of an extracellular mediator, i.e., a growth factor or cytokine, by a cell followed by the binding of that mediator to receptors on the surface of the secreting cell to initiate signaling. In a less strict sense this definition will also include interactions with receptors on neighboring cells when these cells are of the same type with respect to differentiation or function such as in an epithelial lining (Figure 1). In contrast, paracrine signaling occurs between different types of cells, i.e., an epithelial/carcinoma cell and a CAF or a T cell (Figure 1). For several growth factors there is now evidence that the (mitogenic) signal may be transduced without factor secretion. In these instances, the growth factor appears to interact with its receptor within the cell, i.e., in cultured hepatocytes, creating a “private” autocrine or intracrine loop [9,10], in contrast to the classical “public” autocrine loop [9] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Cartoon illustrating the principles of autocrine, intracrine and paracrine TGF-β signaling. Autocrine interactions are indicated by green arrows, intracrine interactions by black arrows, and paracrine interactions by blue arrows (stimulatory) or red lines (inhibitory). Paracrine interactions can be unidirectional or bidirectional/reciprocal. CAF, cancer-associated fibroblast; BM, basement membrane.

Autocrine stimulation often operates in autocrine loops, a type of interaction, in which a cell produces a mediator, for which it has receptors that upon activation promote—in a direct or indirect fashion—expression of the same mediator, allowing the cell to repeatedly autostimulate itself. As an alternative to this positive feedback or feedforward loop, the mediator may balance its own expression by inducing, or suppressing, a second factor that regulates this same mediator in an opposite fashion to provide negative feedback.

Whereas loss or attenuation of TGF-β signaling is permissive for transformation, blocking receptor function in metastatic breast cancer (BC) cells has been shown to inhibit survival, EMT, invasiveness, and metastatic dissemination, suggesting that TGF-β promotes tumor development and malignancy through autocrine and/or paracrine mechanisms [11]. In contrast, autocrine TGF-β (aTGF-β) may also attenuate tumor progression, i.e., by its ability to prevent escape from oncogene-induced senescence (OIS). Based on this observation, aTGF-β has been suggested to be part of a cellular anti-transformation network [12], adding further support to its dual nature in cancer biology.

Although derived from the same genes, exogenous and endogenously produced TGF-β may have different and sometimes antagonistic effects depending on cell type, context, tumor stage and effective concentration or duration of exposure. The outcome is further complicated by the complex process of TGF-β activation [3] and the unique mode of receptor activation, which allows the cells to fine-tune their sensitivity to exogenous ligand in a spatial, temporal and concentration-dependent manner [13]. In addition, TGF-β1 can induce its own expression [14,15] and that of its receptors [16], while the receptors, in addition to canonical Smad signaling, can activate several pathways commonly associated with tyrosine kinase receptors [17], with competition among them for access to receptors [18]. Finally, these signaling pathways exhibit extensive crosstalk with tyrosine kinase signaling, i.e., from Ras (see Section 3.8). Moreover, cell lines derived from human microsatellite unstable colorectal cancers (MSI-H CRCs) with truncating mutations in TGFBR2, were not completely refractory to TGF-β, despite the lack of functional TβRII. Since these cells remained sensitive to signaling by endogenously produced TGF-β, at least with respect to invasive abilities [19] (see Section 2.1), aTGF-β and exogenous TGF-β may have different receptor requirements.

2. Autocrine TGF-β in Cancer-Associated Processes

2.1. Cell Proliferation and Apoptosis

A mentioned above, some cell lines derived from MSI-H CRCs were not completely refractory to TGF-β, despite the lack of functional TβRII [19]. Re-expression of TβRII in HCT116 cells restored aTGF-β signaling and reduced proliferation due to induction of p21CIP1 but failed to restore growth-inhibitory responses to exogenous TGF-β, indicating that aTGF-β regulates the cell cycle through a pathway different from exogenous TGF-β [4]. Additionally in MSI-H CRC cell lines, Baker et al. provided evidence for an independent function of TβRI in signaling by aTGF-β. While these cells were capable of binding exogenous TGF-β, a fraction of them failed to respond with signaling activity. The use of a specific inhibitor of TβRI, however, revealed that these remained sensitive to signaling by endogenously produced aTGF-β as evidenced by constitutive activation of Smad2 and repression of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling. Autocrine signaling via TβRI also promoted the invasion of MSI-H CRC cells to a similar extent as that seen in their non-MSI-H counterparts but failed to impact proliferation [19], supporting the idea that endogenous/aTGF-β and exogenous/paracrine TGF-β can mediate different cellular functions.

Treatment of human triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) MDA-MB-231 cells with TGF-β neutralizing antibodies, recombinant human soluble (s) TβRIII, or ectopic expression of sTβRIII, inhibited both anchorage-dependent and -independent cell growth and induced apoptosis in vitro and in vivo, suggesting specific antagonization of aTGF-β signaling and its requirement for the growth and survival of MDA-MB-231 cells [20]. A follow-up study using abrogation of aTGF-β signaling by expression of a dominant-negative (dn) mutant of TβRII or the treatment with a small-molecule TβRI inhibitor significantly increased apoptosis in MCF-7 cells but not in untransformed human mammary epithelial cells (HMECs), suggesting that in transformed BC cells aTGF-β signaling can enhance cell survival by maintaining high and low levels, respectively, of active ERK and p38 [21]. Along the same lines, systemic administration of a sTβRII:Fc fusion protein to mouse mammary tumor virus-polyomavirus middle T antigen (MMTV-PyVmT) transgenic mice increased apoptosis in primary tumors and reduced tumor cell motility, intravasation, and lung metastases [22]. Hoshino and colleagues confirmed that aTGF-β signaling in certain highly metastatic BCs promotes cell survival via inhibition of apoptosis. In addition, they demonstrated by inhibiting endogenous TGF-β signaling with a TβRI kinase inhibitor in cells cultured serum-free that aTGF-β suppressed the expression of the pro-apoptotic protein, Bim [23]. Interestingly, inhibition of aTGF-β signaling in MDA-MB-231 cells reduced p21CIP1 expression and cell growth, suggesting that aTGF-β signaling is required to sustain p21CIP1 levels for positive regulation of cell growth [24].

Human hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells stably expressing a Smad2 mutant, in which the serine residues of the C-terminal SSXS motif were changed to alanine, demonstrated impaired Smad2 signaling and were resistant to growth inhibition by (exogenous) TGF-β. Interestingly, however, forced expression of this mutant induced aTGF-β secretion, which enhanced signaling through Smad3 and Smad4, and up-regulated plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). This is consistent with TGF-β regulating its own synthesis and provides an example for functional specification of signaling by Smad2 and Smad3, which appear to antagonistically regulate aTGF-β production in human HCC [25].

2.2. EMT, Stemness and Cell Motility

There is increasing evidence that after cells have lost their sensitivity to TGF-β-mediated growth inhibition, aTGF-β signaling promotes tumor cell motility and invasiveness. In MDA-MB-231 cells stably expressing dnTβRII basal migration was impaired but could be restored by reconstitution of TGF-β signaling with a constitutively-active (ca) TβRI but not by reconstituting Smad signaling. The caTβRIT204D mutant does not rely on exogenous ligand in order to be able to signal. From the observation that introducing this mutant into cells expressing dnTβRII restored their migratory response and was associated with an increase in AKT and ERK but not Smad2 phosphorylation, the authors concluded that aTGF-β signaling can promote cell motility in a Smad-independent manner [26].

The Neu (erbB2) proto-oncogene product is the murine ortholog of HER2 and like epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR; erbB1) belongs to the erbB family of receptor tyrosine kinases. To determine if the Neu is dominant over TGF-β, Dumont et al. crossed MMTV-Neu mice with MMTV-TGF-β1(S223/225) mice expressing active TGF-β1 in the mammary gland. The bigenic tumors and their metastases were less proliferative than those occurring in MMTV-Neu mice, however, bigenic tumors exhibited lower apoptotic scores and were more locally invasive. Mice harboring bigenic tumors contained a greater number of circulating tumor cells and lung metastases as well as higher levels of activated Smad2, Akt, Erk, p38, Rac1 and more vimentin in the tumor tissues in situ than tumors expressing Neu alone. These changes were inhibited by sTβRII:Fc, suggesting they were activated by aTGF-β. The data indicate that Neu does not abrogate aTGF-β1-mediated antiproliferation but can synergize with aTGF-β1 in accelerating metastatic tumor progression [27]. In a follow-up study, Muraoka-Cook and colleagues addressed the role of TGF-β in the progression of established tumors. To spare the inhibitory effects of TGF-β on early transformation, they generated triple transgenic mice with doxycycline-inducible regulation of active TGF-β1 expression in mammary tumor cells transformed by the PyMT. Conditional induction of TGF-β1 for 2 weeks strongly increased lung metastases without detectable effects on primary tumor cell proliferation or tumor size. Doxycycline-induced active TGF-β1 protein and nuclear Smad2 were restricted to cancer cells, suggesting a causal association between aTGF-β and increased metastasis. The selective effect of aTGF-β on invasion and metastasis was subsequently confirmed by the reverse approach, antisense-mediated inhibition of TGF-β1 in the tumor cells, indicating that the induction and/or activation of TGF-β in hosts with already established TGF-β-responsive cancers can rapidly accelerate metastatic progression [28].

Another study investigated the role of aTGF-β signaling in the survival and metastatic potential of mammary CSCs, utilizing a novel murine mammary cell line, NMuMG-ST, which acquired CSC phenotypes during spontaneous transformation of the parental cell line, NMuMG. In NMuMG-ST cells, aTGF-β signaling promoted anchorage-independent growth, resistance to serum deprivation-induced apoptosis, EMT, sphere formation, and the expression of stem cell markers. Upon injection into mice, these cells underwent apoptosis and generated less lung metastases than control cells, while the sizes of xenograft tumors were not different, indicating that aTGF-β signaling is involved in the maintenance and survival of murine BC stem cells and their enhanced metastatic ability [29].

During tumor pathogenesis, changes in cell phenotypes are induced by contextual signals that epithelial cells receive from the tumor microenvironment (TME) [6] and that include TGF-β and Wnt ligands. Their signaling pathways collaborate in several feedback loops to activate the EMT program and thereafter function in an autocrine fashion to maintain the resulting mesenchymal state [30]. Tian et al. have constructed a mathematical model for the EMT core regulatory network and applying this model to TGF-β-induced EMT they found that EMT is a sequential two-step program, in which an epithelial cell first is converted to a partial EMT (p-EMT) state and then to the mesenchymal state, depending on the strength and duration of TGF-β stimulation. Mechanistically, the process is governed by coupled reversible and irreversible bistable switches. While the Snail1/miR-34 double-negative feedback loop regulates the initiation of EMT and is reversible, the Zeb/miR-200 feedback loop controls the establishment of the mesenchymal state and is irreversible. Of note, irreversibility of the second switch and maintenance of EMT is assured by an aTGF-β/miR-200 feedback loop [31]. Likewise, in mammary MCF10A cells, stabilization of the mesenchymal state also involves a novel autocrine mechanism composed of a circuit with TGF-β, miR-200, and Snail1 [32].

Hepatic progenitor cells usually expand in chronic liver injury and contribute to liver regeneration by differentiating into hepatocytes and cholangiocytes. During this process, they acquire p-EMT states that are maintained by aTGF-β, activin A and Smad signaling [33]. Likewise, during in vitro differentiation to the hepatic lineage, human embryonic stem cells undergo a sequential EMT-mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET) process with an obligatory intermediate mesenchymal phase. Remarkably, aTGFβ signaling mediates a synchronous EMT that accompanies activin A-induced formation of definitive endoderm and is followed by a MET process [34].

Autocrine TGF-β signaling also plays an essential role in the retention of stemness of glioma-initiating cells (GICs). Treatment of GICs with TGF-β signaling inhibitors promoted their differentiation, resulting in decreased tumorigenicity as evidenced by lower lethal potency in intracranial transplantation assays. In additional experiments, the authors identified an essential pathway for GICs involving aTGF-β, Sox4 and Sox2, whose disruption could be a therapeutic strategy against gliomas [35].

Yang and coworkers, by modulating TβRII levels, found that aTGF-β signaling transcriptionally targets human telomerase reverse transcriptase (hTERT) for inhibition of telomerase activity. Restoration of aTGF-β activity in TβRII-deficient HCT116 cells after re-expression of TβRII led to a reduction of hTERT mRNA levels and telomerase activity, whereas suppression of aTGF-β signaling in MCF-7 cells by dnTβRII had the reverse effect [36].

3. Autocrine TGF-β in the Regulation of Specific Proteins

3.1. Receptor Tyrosine Kinases, Adapter Proteins, E3 Ligases, and Small GTPases

Up-regulation and activation of the receptor tyrosine kinase, Axl, in EMT-transformed hepatoma cells caused phosphorylation of Smad3 in its linker region, resulting in the induction of PAI-1, matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9), and Snail as well as TGF-β1 secretion in mesenchymal HCC cells. Consistent with this, high Axl expression in HCC patient samples correlated with elevated vessel invasion of HCC cells, higher risk of tumor recurrence after liver transplantation, and lower patient survival [37]. Autocrine TGF-β also increased the endogenous levels of the adapter protein Crk and collaborates with Crk to form a positive feedback loop to facilitate EMT in A549 human lung adenocarcinoma cells through differential regulation of Rac1/Snail and RhoA/Slug [38].

TGF-β drives EMT through TβRI, which initiates both Smad-dependent and independent reprogramming of gene expression. TβRI is a dual-specificity kinase, which has tyrosine kinase activity and can activate the ERK mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway through recruitment and tyrosine phosphorylation of the adapter protein, ShcA [17]. Interestingly, ShcA protects the epithelial integrity of nontransformed cells against EMT and EMT-associated events by competing with Smad3 for TGF-β receptor binding and blocking aTGF-β/Smad signaling and target gene expression [18].

The tumor suppressor PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog on chromosome ten) is a substrate for XIAP E3 ubiquitin-protein-ligase activity, which decreases PTEN protein levels. In turn, XIAP gene expression and function is positively regulated by all three TGF-β isoforms in a Smad and NFκB-dependent manner. Moreover, its constitutive expression in endometrial and cervical carcinoma cells depends on aTGF-β signaling, together implicating aTGF-β/Smad signaling in XIAP-mediated downregulation of PTEN [39].

Recent data from the author’s group have shown that RAC1b, a splice isoform of the human RAC1 gene, is a powerful inducer of aTGF-β1 production and signaling in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) and BC-derived cells [40] and is involved in the inhibition of EMT and cell migration. We have recently identified a novel tumor-suppressive pathway, in which RAC1b-driven aTGF-β1 induces Smad3 expression in an exogenous TGF-β-independent manner. Smad3 was subsequently identified as a potent suppressor of EMT and cell migration via its ability to maintain E-cadherin expression and to induce expression of the small proteoglycan biglycan, an extracellular TGF-β binding protein and inhibitor of TGF-β signaling [41]. Of note, in renal tubular epithelial cells, exposure to exogenous TGF-β1 for longer time periods (5–7 days) decreased Smad3 levels, which paralleled the EMT process. Down-regulation of Smad3 could be part of a feedback loop controlling TGF-β signaling in a cell phenotype-specific manner [42]. However, based on our results, a reduction in Smad3 abundance may also remove a barrier to induction of EMT and invasive activities [41], mediating relief from the tumor-suppressive effects of aTGF-β1 and RAC1b. In addition, we observed that in the same cells, aTGF-β1 promoted proliferation and therefore antagonized the action of exogenous (recombinant human) TGF-β1 on these cells [43]. Very recent results with cells, in which the endogenous TGFB1 gene had been silenced, indicate that aTGF-β1 can even act an endogenous inhibitor of exogenous, recombinant human (rh)TGF-β1 [44].

3.2. Transcription Factors

Overexpression in mammary epithelial cells of Krüppel-like zinc finger protein ZNF217, a transcription factor (TF) and candidate oncogene in BC, stimulated EMT, migration and invasion in vitro and promoted the development of lung or node metastases in mice in vivo. TGF-β/Smad signaling was identified as a major driver of ZNF217-induced EMT and a TGF-β autocrine loop maintained by ZNF217-mediated up-regulation of TGFB2 or TGFB3 sustained activation of the TGF-β pathway in ZNF217-overexpressing BC cells [45]. Likewise, expression of the T-box TF, Brachyury, is enhanced during TGF-β1-induced EMT in various human cancer cell lines. Brachyury over-expression promoted up-regulation of TGF-β1 through activation of the TGFB1 promoter, while inhibition of TGF-β1 signaling decreased the expression of this TF, eventually resulting in the establishment of a positive feedback loop between Brachyury and aTGF-β1 in mesenchymal-like tumor cells [46]. Another TF, forkhead box F2 (FOXF2), is over-expressed in basal-like breast cancer (BLBC) cells and suppressed EMT and malignancy of these cells. FOXF2 repressed TGF-β/Smad signaling in BLBC cells, while, in turn, TGF-β down-regulated FOXF2 expression through induction of miR-182-5p. FOXF2-deficient BLBC cells converted to a CAF-like phenotype and showed a propensity for metastases formation in visceral organs by increasing aTGF-β signaling and by making neighboring cells more aggressive through enhancing signaling by paracrine TGF-β [47].

Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) is characterized by aberrantly high levels of TGF-β2, a result of TGF-β2 auto-induction through a positive autocrine feedback loop. The TF, cAMP-responsive element-binding protein 1 (CREB1), was identified as the main perpetuator of this circuit. CREB1 binding to the TGFB2 promoter in cooperation with Smad3 was required for TGF-β2 to activate transcription. Since in patient-derived in vivo models of glioblastoma, CREB1 levels have been found to determine the expression of TGFB2, CREB1 has been proposed a biomarker to stratify GBM patients for anti-TGF-β treatments and eventually as a therapeutic target in anti-TGF-β therapies [48].

ATF3, an adaptive-response gene, is induced by various stromal signals, i.e., TGF-β, in MCF10CA1a BC cells and is crucial for TGF-β-induced up-regulation of Snail, Slug and Twist, and enhancement of cell motility. Since ATF3 also up-regulates the TGFB gene(s), it forms a positive feedback loop to drive TGF-β signaling. Not surprisingly, therefore, ectopic expression of ATF3 led to EMT and features associated with BC-initiating cells [49].

Paraspeckle component 1 (PSPC1) is up-regulated and associated with poor survival in cancer patients. It enhances EMT and stem cell phenotypes in multiple cell types as well as metastasis in mouse models of spontaneously arising cancers. PSPC1 is a master activator of EMT-TFs, increases TGF-β1 secretion to amplify aTGF-β1 signaling, and controls the pro-metastatic switch of TGF-β1 from a tumor suppressor to a tumor promoter [50].

NCI-H358 non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cells engineered to express Snail, Zeb1 or activated TGF-β exhibited aTGFβ expression and phenotypic changes consistent with EMT and a shift to a more invasive phenotype. Although Snail and Zeb1 were sufficient to induce EMT in these cells, aTGFβ induced a more complete EMT phenotype [51].

3.3. MicroRNAs

The aTGF-β/Zeb/miR-200 signaling network regulates plasticity between epithelial and mesenchymal states in invasive ductal carcinomas, including those of the human breast. Both the induction and maintenance of a stable mesenchymal phenotype requires the establishment of aTGF-β signaling to drive sustained ZEB expression, while prolonged aTGF-β signaling induces reversible DNA methylation of the miR-200 loci with corresponding changes in miR-200 levels [52]. Rateitschak and colleagues have developed kinetic models to describe how aTGF-β signaling induces and maintains an EMT by up-regulating ZEB1 and ZEB2, which in turn represses the expression of miR-200b/c family members. When combined with data from patient-derived tumor cells, their algorithms can predict the minimal amount of an inhibitor required to induce a MET [53]. In A549 cells, TGF-β1 cooperates with yet another miR, hsa-miR-21, in the induction of EMT. Intriguingly, TGF-β1 was found to induce hsa-miR-21 expression and both are involved in autocrine and paracrine circuits that regulate the EMT status of lung cancer cells [54]. In NSCLC tissues, expression of another miR, miR-124, is significantly impaired and is associated with metastasis. Restoring miR-124 expression in NSCLC cells reduced migration, invasion and metastasis. Smad4 was identified as a novel target gene of miR-124, suggesting that a feedback loop between miR-124 and the TGF-β pathway may play a crucial role in NSCLC metastasis [55]. In lung adenocarcinoma H1299 xenograft assays, stable expression of miR-206 suppressed both tumor growth and metastasis in mice. Profiling of xenograft tumors revealed a network of genes involved in TGF-β signaling that were regulated by miR-206, i.e., TGFB1, direct transcriptional targets of Smad3, and components of the ECM involved in TGF-β activation, i.e., thrombospondin-1. Hence, miR-206 can suppress tumor progression and metastasis by limiting the production of aTGF-β [56]. In BC, decreased miR-206 expression is associated with advanced clinical stage and lymph node metastasis, and miR-206 overexpression in ER-positive cell lines markedly impaired EMT, migration, invasion, and inhibited TGFB1 transcription and aTGF-β1 production [57]. Stabilization of TGFB1 mRNA, its translation and expression, TGF-β1 dimer formation and aTGF-β1-induced EMT was also promoted by N6-methyladenosine, the most abundant modification on eukaryotic mRNA [58].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms22020977