Coffee is one of the most consumed beverages in the world, and its popularity has prompted the necessity to constantly increase the variety and improve the characteristics of coffee as a general commodity. The popularity of coffee as a staple drink has also brought undesired side effects, coffee production, processing and consumption are all accompanied by impressive quantities of coffee-related wastes which can be a threat to the environment. In this review, we integrated the main studies on fermentative yeasts used in coffee-related industries with an emphasis on two different directions: (1) the role of yeast strains in the postharvest processing of coffee, the possibilities to use them as starting cultures for controlled fermentation and their impact on the sensorial quality of processed coffee, and (2) the potential to use yeasts to capitalize on coffee wastes - especially spent coffee grounds—in the form of eco-friendly biomass, biofuel or fine chemical production.

- coffee

- yeast

- spent coffee grounds

- bioethanol

1. Introduction

Along with tea, coffee is one of the most important habitual and social beverages in the modern world. Coffee represents an essential worldwide commodity and the major export commodity in around 70 tropical and subtropical countries [1]. In December 2020, the United States Department of Agriculture forecast the world coffee production for 2020/2021 at 175.5 million bags (60 kg per bag), which represents an increase of 7 million bags compared to the previous year [2]. The world market is dominated by two species of coffee: Coffea arabica (Arabica) and Coffea canephora (Robusta). Arabica is native to Ethiopia, while Robusta is native to Central Africa.

Due to the high content of caffeine and of other valuable nutraceuticals such as caffeic acid, chlorogenic acid and a plethora of other polyphenols with antioxidant proprieties, coffee has important and well documented pharmacological significance. The chemical composition (organic acids, sugars, aromas including heterocyclic compounds) determines the strength, the taste and the flavor, but the quality of the coffee also depends on physical factors (size, color and defective beans) [5].

Yeasts, especially from the genus Saccharomyces, have been used since ancient times for baking, brewing, distilling, winemaking and other fermented beverage production (e.g., sake, palm wine) [8]. S. cerevisiae is one of the most studied microorganisms in both fundamental and industrial research, and the study of S. cerevisiae under wine fermentation conditions is one of the oldest and most representative research in biotechnology [9]. The natural habitats of yeasts include fruits, cacti, the bark of trees, soil, etc. A multitude of strains have been isolated from different sources and environments (industrial, laboratory, wild isolates); among numerous sources, yeasts were also isolated from unroasted coffee [10]. S. cerevisiae is highly used in the fermentation processes involved in coffee production or valorization of coffee waste residue. Besides S. cerevisiae, numerous yeast species from different genera have been detected in the coffee processing steps, which include Pichia, Candida, Saccharomyces and Torulaspora [11,12]. The coffee’s aroma is the result of a mix of over 800 volatile chemical compounds.

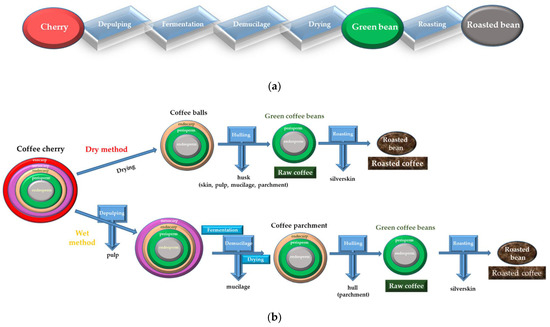

2. Yeasts and Coffee Processing

2.8. Special Compounds in Yeast-Fermented Coffee

3. Yeasts as Toolboxes for Capitalization of Coffee Wastes

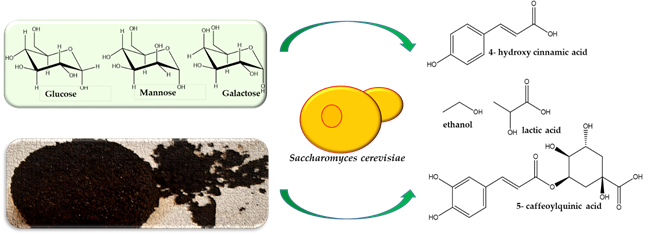

3.3. Spent Coffee Grounds and Fine Chemicals

4. Concluding Remarks

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/fermentation7010009

References

- 1. FAO. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4985e.pdf (ac-cessed on 17 December 2020).2. USDA. United States Department for Agriculture. Available online: https://apps.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/circulars/coffee.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2020).3. Martı́n, M.L.; Pablos, F.; González, A.G. Discrimination between arabica and robusta green coffee varieties according to their chemical composition. Talanta 1998, 46, 1259–1264, doi:10.1016/S0039-9140(97)00409-8.4. Pérez, S.B.Y.; Saldaña-Trinidad, S. Chemistry and biotransformation of coffee by products to biofuels, In The Question of Caffeine, Latosinska, J.N., Latosinska, M., Eds.; InTech: London, UK, 2017; pp. 143–161, doi:10.5772/65133.5. Cheng, B.; Smyth, H.E.; Furtado, A.; Henry, R.J. Slower development of lower canopy beans produces better coffee. J. Exp. Bot. 2020, 71, 4201–4214, doi:10.1093/jxb/eraa151.6. Bressani, A.P.P.; Martinez, S.J.; Sarmento, A.B.I.; Borém, F.M.; Schwan, R.F. Organic acids produced during fermentation and sensory perception in specialty coffee using yeast starter culture. Food Res. Int. 2020, 128, 108773, doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2019.108773.7. Sunarharum, W.B.; Williams, D.J.; Smyth, H.E. Complexity of coffee flavor: A compositional and sensory perspective. Food Res. Int. 2014, 62, 315–325, doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2014.02.030.8. Camarasa, C.; Sanchez, I.; Brial, P.; Bigey, F.; Dequin, S. Phenotypic landscape of Saccharomyces cerevisiae during wine fer-mentation: Evidence for origin-dependent metabolic traits. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e25147, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025147.9. Ruta, L.L.; Farcasanu, I.C. Anthocyanins and anthocyanin-derived products in yeast-fermented beverages. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 182, doi:10.3390/antiox8060182.10. Ludlow, C.L.; Cromie, G.A.; Garmendia-Torres, C.; Sirr, A.; Hays, A.; Field, C.; Jeffery, E.W.; Fay, J.C.; Dudle, A.D. Inde-pendent origins of yeast associated with coffee and cacao fermentation. Curr. Biol. 2016, 26, 965–971, doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.02.012.11. De Bruyn, F.; Zhang, S.J.; Pothakos, V.; Torres, J.; Lambot, C.; Moroni, A.V.; Callanan, M.; Sybesma, W.; Weckx, S.; De Vuyst, L. Exploring the impacts of postharvest processing on the microbiota and metabolite profiles during green coffee bean production. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 83, e02398–16, doi:10.1128/AEM.02398-16.12. Evangelista, S.R.; Miguel, M.G.; de Souza Cordeiro, C.; Silva, C.F.; Pinheiro, A.C.; Schwan, R.F. Inoculation of starter cul-tures in a semi-dry coffee (Coffea arabica) fermentation process. Food Microbiol. 2014, 44, 87–95, doi:10.1016/j.fm.2014.05.013.13. Vilela, D.M.; Pereira, G.V.; Silva, C.F.; Batista, L.R.; Schwan, R.F. Molecular ecology and polyphasic characterization of the microbiota associated with semi-dry processed coffee (Coffea arabica L.). Food Microbiol. 2010, 27, 1128–1135, doi:10.1016/j.fm.2010.07.024.14. Silva, C.F.; Batista, L.R.; Abreu, L.M.; Dias, E.S.; Schwan, R.F. Succession of bacterial and fungal communities during natural coffee (Coffea arabica) fermentation. Food Microbiol. 2008, 25, 951–957, doi:10.1016/j.fm.2008.07.003.15. Vinícius de Melo Pereira, G.; Soccol, V.T.; Brar, S.K.; Neto, E.; Soccol, C.R. Microbial ecology and starter culture technology in coffee processing. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 2775–2788, doi:10.1080/10408398.2015.1067759.16. Duarte, G.S.; Pereira, A.A.; Farah, A. Chlorogenic acids and other relevant compounds in Brazilian coffees processed by semi-dry and wet post-harvesting methods. Food Chem. 2010, 118, 851–855, doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.05.042.17. Batista, L.R.; Chalfoun, S.M.; Batista, C.F.S.; Schwan, R.F. Coffee: Types and production. In The Encyclopedia of Food and Health, 1st ed.; Caballero, B., Finglas, P., Toldrá, F., Eds.; Academic Press: Oxford, Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 244.18. Silva, C.F. Microbial activity during coffee fermentation. In Cocoa and Coffee Fermentations; Schwan, R.F., Fleet, G.H., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014, pp. 368–423.19. Murthy, P.S.; Naidu, M.M. Sustainable management of coffee industry by-products and value addition—A review. Resour. Conserv. Recy. 2012, 66, 45–58, doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2012.06.005.20. Silva, C.F.; Vilela, D.M.; de SouzaCordeiro, C.; Duarte, W.F.; Dias, D.R.; Schwan, R.F. Evaluation of a potential starter cul-ture for enhances quality of coffee fermentation. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 29, 235–247, doi:10.1007/s11274-012-1175-2.21. Avallone, S.; Brillouet, J.M.; Guyot, B.; Olguin, E.; Guiraud, J.P. Involvement of pectinolytic microorganisms is coffee fer-mentation. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2002, 37, 191–198, doi:10.1046/j.1365-2621.2002.00556.x.22. Masoud, W.; Jespersen, L. Pectin degrading enzymes in yeasts involved in fermentation of Coffea arabica in East Africa. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 110, 291–296, doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.04.030.23. Ulloa Rojas, J.B.; Verreth, J.A.; Amato, S.; Huisman, E.A. Biological treatments affect the chemical composition of coffee pulp. Bioresour. Technol. 2003, 89, 267–274, doi:10.1016/s0960-8524(03)00070-1.24. Bekalo, S.A.; Reinhardt, H. Fibers of coffee husk and hulls for the production of particleboard. Mater. Struct. 2010, 43, 1049–1060, doi:10.1617/s11527-009-9565-0.25. Aristizábal, V.M.; Chacón-Perez, Y.; Carlos, A.; Alzate, C. The biorefinery concept for the industrial valorization of coffee processing by-products. In Handbook of Coffee Processing by-Products; Galanakis, C.M., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, Cam-bridge, MA, USA, 2017, pp. 63–92, doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-811290-8.00003-7.26. Lee, S.J.; Kim, M.K.; Lee, K.G.; Effect of reversed coffee grinding and roasting process on physicochemical properties in-cluding volatile compound profiles. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2017, 44, 97–102 doi:10.3390/s20113123.27. Martinez, S.J.; Bressani, A.P.P.; Miguel, M.G.D.C.P.; Dias, D.R.; Schwan, R.F. Different inoculation methods for semi-dry processed coffee using yeasts as starter cultures. Food Res. Int. 2017, 102, 333–340, doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2017.09.096.28. Avallone, S.; Guyot, B.; Brillouet, J.M.; Olguin, E.; Guiraud, J.P. Microbiological and biochemical study of coffee fermenta-tion. Curr. Microbiol. 2001, 42, 252–256, doi:10.1007/s002840110213.29. Haile, M.; Kang, W.H. The role of microbes in coffee fermentation and their impact on coffee quality. J. Food Qual. 2019, 2019, 4836709, doi:10.1155/2019/4836709.30. Haile, M.; Kang, W.H. Isolation, identification, and characterization of pectinolytic yeasts for starter culture in coffee fer-mentation. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 401, doi:10.3390/microorganisms7100401.31. Massawe, G.A.; Lifa, S.J. Yeasts and lactic acid bacteria coffee fermentation starter cultures. Int. J. Postharvest Technol. Innov. 2010, 2, 41–80, doi:10.1504/IJPTI.2010.038187.32. Lee, L.W.; Cheong, M.W.; Curran, P.; Yu, B.; Liu, S.Q. Modulation of coffee aroma via the fermentation of green coffee beans with Rhizopusoligosporus: I. Green coffee. Food Chem. 2016, 211, 916–924, doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.05.076.33. Lee, L.W.; Cheong, M.W.; Curran, P.; Yu, B.; Liu, S.Q. Modulation of coffee aroma via the fermentation of green coffee beans with Rhizopusoligosporus: II. Effects of different roast levels. Food Chem. 2016, 211, 925–936, doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.05.073.34. Agate, A.D.; Bhat, J.V. Role of pectinolytic yeasts in the degradation of mucilage layer of Coffea robusta cherries. Appl. Micro-biol. 1966, 14, 256–260.35. Martins, P.M.M.; Ribeiro, L.S.; Miguel, M.G.D.C.P.; Evangelista, S.R.; Schwan, R.F. Production of coffee (Coffea arabica) inocu-lated with yeasts: Impact on quality. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 5638–5645, doi:110.1002/jsfa.9820.36. Dandekar, R.; Fegade, B.; Bhaskar, V.H. GC-MS analysis of phytoconstituents in alcohol extract of Epiphyllumoxy petalum leaves. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2015, 4, 149–154.37. Martinez, S.J.; Bressani, A.P.P.; Dias, D.R.; Simão, J.B.P.; Schwan, R.F. Effect of bacterial and yeast starters on the formation of volatile and organic acid compounds in coffee beans and selection of flavors markers precursors during wet fermentation. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1287, doi:10.3389/fmicb.2019.01287.38. De Melo Pereira, G.V.; Soccol, V.T.; Pandey, A.; Medeiros, A.B.; Andrade Lara, J.M.; Gollo, A.L.; Soccol, C.R. Isolation, selec-tion and evaluation of yeasts for use in fermentation of coffee beans by the wet process. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014, 188, 60–66, doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2014.07.008.39. De Melo Pereira, G.V.; Neto, E.; Soccol, V.T.; Medeiros, A.B.P.; Woiciechowski, A.L.; Soccol, C.R. Conducting starter cul-ture-controlled fermentations of coffee beans during on-farm wet processing: Growth, metabolic analyses and sensorial ef-fects. Food Res. Int. 2015, 75, 348–356, doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2015.06.027.40. Elhalis, H.; Cox, J.; Zhao, J. Ecological diversity, evolution and metabolism of microbial communities in the wet fermenta-tion of Australian coffee beans. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 321, 108544, doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2020.108544.41. Pehl, C.; Pfeiffer, A.; Wendl, B.; Kaess, H. The effect of decaffeination of coffee on gastro-oesophageal reflux in patients with reflux disease. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 1997, 11, 483–486, doi:10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.00161.x.42. Rubach, M.; Lang, R.; Skupin, C.; Hofmann, T.; Somoza, V. Activity-guided fractionation to characterize a coffee beverage that effectively down-regulates mechanisms of gastric acid secretion as compared to regular coffee. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 4153–4161, doi:10.1021/jf904493f.43. Rubach, M.; Lang, R.; Seebach, E.; Somoza, M.M.; Hofmann, T.; Somoza, V. Multi-parametric approach to identify coffee components that regulate mechanisms of gastric acid secretion. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2012, 56, 325–335, doi:10.1002/mnfr.201100453.44. Tinoco, N.A.B.; Pacheco, S.; Godoy, R.L.O.; Bizzo, H.R.; de Aguiar, P.F.; Leite, S.G.F.; Rezende, C.M. Reduction of βN-alkanoyl-5-hydroxytryptamides and diterpenes by yeast supplementation to green coffee during wet processing. Food Res. Int. 2019, 115, 487–492, doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2018.10.007.45. Velmourougane, K.; Bhat, R.; Gopinandhan, T.N.; Panneerselvam, P. Impact of delay in processing on mold development, ochratoxin-A and cup quality in Arabica and Robusta coffee. World J. Microb. Biot. 2011, 27, 1809–1816, doi:10.1007/s11274-010-0639-5.46. Ribeiro, L.S.; Miguel, M.G.; Evangelista, S.R.; Machado Martins, P.M.; van Mullem, J.; Belizario, M.H.; Schwan, R.F. Behavior of yeast inoculated during semi-dry coffee fermentation and the effect on chemical and sensorial properties of the final beverage. Food Res. Int. 2017, 92, 26–32, doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2016.12.011.47. Wang, C.; Sun, J.; Lassabliere, B.; Yu, B.; Liu, S.Q. Coffee flavour modification through controlled fermentations of green coffee beans by Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Pichia kluyveri: Part I. Effects from individual yeasts. Food Res. Int. 2020, 136, 109588, doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109588.48. Bressani, A.P.P.; Martinez, S.J.; Evangelista, S.R.; Ribeiro, D.D.; Schwan, R.F. Characteristics of fermented coffee inoculated with yeast starter cultures using different inoculation methods. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 92, 212–219, doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2018.02.029.49. Pereira, L.L.; Guarçoni, R.C.; Pinheiro, P.F.; Osório, V.M. ; Pinheiro, C.A.; Moreira, T.R.; Ten Caten, C.S. New propositions about coffee wet processing: Chemical and sensory perspectives. Food Chem. 2020, 310, 125943, doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125943.50. Brando, C.H.J.; Brando, M.F. Methods of coffee fermentation and drying. In Cocoa and Coffee Fermentations; Schwan, R.F., Fleet, G.H., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; pp. 367–396.51. da Mota, M.C.B.; Batista, N.N.; Rabelo, M.H.S.; Ribeiro, D.E.; Borém, F.M.; Schwan, R.F. Influence of fermentation conditions on the sensorial quality of coffee inoculated with yeast. Food Res. Int. 2020, 136, 109482, doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109482.52. Yu, X.; Zhao, M.; Liu, F.; Zeng, S.; Hu, J. Identification of 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-4H-pyran-4-one as a strong antioxidant in glucose-histidine Maillard reaction products. Food Res. Int. 2013, 51, 397–403, doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2012.12.044.53. Cutzach, I.; Chatonnet, P.; Dubourdieu, D. Study of the formation mechanisms of some volatile compounds during the ag-ing of sweet fortified wines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 2837–2846, doi:10.1021/jf981224s.54. Moreira, R.F.A.; Trugo, L.C.; Maria, C.A.B. Volatile components in roasted coffee. Part II. Aliphatic, alicyclic and aromatic compounds. Quím. Nova 2000, 23, 195–201, doi:10.1590/S0100-40422000000200010.55. Campos-Vega, R.; Loarca-Piña, G.; Vergara-Castañeda, H.A.; Oomah, B.D. Spent coffee grounds: A review on current re-search and future prospects. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2015, 45, 24–36, doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2015.04.012.56. Mussatto, S.J.; Machado, E.M.S.; Martins, S.; Teixeira, J.A. Production, composition and application of coffee and its industri-al residues. Food Bioprocess. Technol. 2011, 4, 661–672, doi:10.1007/s11947-011-0565-z.57. Hughes, S.R.; López-Núñez, J.C.; Jones, M.A.; Moser, B.R.; Cox, E.J.; Lindquist, M.; Galindo-Leva, L.A.; Riaño-Herrera, N.M.; Rodriguez-Valencia, N.; Gast, F.; et al. Sustainable conversion of coffee and other crop wastes to biofuels and bioproducts using coupled biochemical and thermochemical processes in a multi-stage biorefinery concept. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 8413–8431, doi:10.1007/s00253-014-5991-1.58. Choi, I.S.; Wi, S.G.; Kim, S.B.; Bae, H.J. Conversion of coffee residue waste into bioethanol with using popping pretreat-ment. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 125, 132–137, doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2012.08.080.59. da Silveira, J.S.; Durand, N.; Lacour, S.; Belleville, M.P.; Perez, A.; Loiseau, G.; Dornier, M. Solid-state fermentation as a sus-tainable method for coffee pulp treatment and production of an extract rich in chlorogenic acids. Food Bioprod. Process. 2019, 115, 175–184, doi:10.1016/j.fbp.2019.04.001.60. Pandey, A.; Soccol, C.R.; Nigam, P.; Brand, D.; Mohan, R.; Roussos, S. Biotechnological potential of coffee pulp and coffee husk for bioprocesses. Biochem. Eng. J. 2000, 6, 153–162, doi:10.1016/s1369-703x(00)00084-x.61. Kim, K.; Tsao, R.; Yang, R.; Cui, S. Phenolic acid profiles and antioxidant activities of wheat bran extracts and the effect of hydrolysis conditions. Food Chem. 2006, 95, 466–473, doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.01.032.62. Acosta-Estrada, B.A.; Gutiérrez-Uribe, J.A.; Serna-Saldívar, S.O. Bound phenolics in foods, a review. Food Chem. 2014, 152, 46–55, doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.11.093.63. Lin, C.S.K.; Pfaltzgraff, L.A.; Herrero-Davila, L.; Mubofu, E.B.; Solhy, A.; Clark, J.H.; Koutinas, A.; Kopsahelis, N.; Stamate-latou, K.; Dickson, F.; et al. Food waste as a valuable resource for the production of chemicals, materials and fuels. Current situation and global perspective. Energy Environ. Sci. 2013, 6, 426–464, doi:10.1039/C2EE23440H.64. Nguyen, Q.A.; Cho, E.; Trinh, L.T.P.; Jeong, J.S.; Bae, H.J. Development of an integrated process to produce d-mannose and bioethanol from coffee residue waste. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 244 Pt 1, 1039–1048, doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2017.07.169.65. Hughes, S.R.; Sterner, D.E.; Bischoff, K.M.; Hector, R.E.; Dowd, P.F.; Qureshi, N.; Bang, S.S.; Grynaviski, N.; Chakrabarty, T.; Johnson, E.T.; et al. Three-plasmid SUMO yeast vector system for automated high-level functional expression of val-ue-added co-products in a Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain engineered for xylose utilization. Plasmid 2009, 61, 22–38, doi:10.1016/j.plasmid.2008.09.001.66. Hughes, S.R.; Cox, E.J.; Bang, S.S.; López-Núñez, J.C.; Saha, B.C.; Qureshi, N.; Gibbons, W.R.; Fry, M.R.; Moser, B.R.; Bischoff, K.M.; et al. Process for assembly and transformation into saccharomyces cerevisiae of a synthetic yeast artificial chromo-some containing a multigene cassette to express enzymes that enhance xylose utilization designed for an automated plat-form. J. Lab. Autom. 2015, 20, 621–635, doi:10.1177/2211068215573188.67. Rocha, M.V.; de Matos, L.J.; Lima, L.P.; Figueiredo, P.M.; Lucena, I.L.; Fernandes, F.A.; Gonçalves, L.R. Ultrasound-assisted production of biodiesel and ethanol from spent coffee grounds. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 167, 343–348, doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2014.06.032.68. Gouvea, B.M.; Torres, C.; Franca, A.S.; Oliveira, L.S.; Oliveira, E.S. Feasibility of ethanol production from coffee husks. Bio-technol. Lett. 2009, 31, 1315–1319, doi:10.1007/s10529-009-0023-4.69. Kwon, E.E.; Yi, H.; Jeon, Y.J. Sequential co-production of biodiesel and bioethanol with spent coffee grounds. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 136, 475–480, doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2013.03.052.70. Ravindran, R.; Sarangapani, C.; Jaiswal, S.; Cullen, P.J.; Jaiswal, A.K. Ferric chloride assisted plasma pretreatment of ligno-cellulose. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 243, 327–334, doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2017.06.123.71. Harsono, S.S.; Fauzi, M.; Purwono, G.S.; Soemarno, D. Second generation bioethanol from Arabica coffee waste processing at small holder plantation in Ijen Plateau region of East Java. Procedia Chem. 2015, 14, 408–413, doi:10.1016/j.proche.2015.03.055.72. Lee, J.W.; In, J.H.; Park, J.B.; Shin, J.; Park, J.H.; Sung, B.H.; Sohn, J.H.; Seo, J.H.; Park, J.B.; Kim, S.R.; et al. Co-expression of two heterologous lactate dehydrogenases genes in Kluyveromyces marxianus for l-lactic acid production. J. Biotechnol. 2017, 241, 81–86, doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.11.015.73. Kim, J.W.; Jang, J.H.; Yeo, H.J.; Seol, J.; Kim, S.R.; Jung, Y.H. Lactic acid production from a whole slurry of acid-pretreated spent coffee grounds by engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2019, 189, 206–216, doi:10.1007/s12010-019-03000-6.74. Menezes, E.G.; do Carmo, J.R.; Menezes, A.G.; Alves, J.G.; Pimenta, C.J.; Queiroz, F. Use of different extracts of coffee pulp for the production of bioethanol. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2013, 169, 673–687, doi:10.1007/s12010-012-0030-0.75. Bonilla-Hermosa, V.A.; Duarte, W.F.; Schwan, R.F. Utilization of coffee by-products obtained from semi-washed process for production of value-added compounds. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 166, 142–150, doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2014.05.031.76. Moreira, M.D.; Melo, M.M.; Coimbra, J.M.; Reis, K.C.D.; Schwan, R.F.; Silva, C.F. Solid coffee waste as alternative to produce carotenoids with antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. Waste Manag. 2018, 82, 93–99, doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2018.10.017.