In children and adolescents, chronic low-grade inflammation has been implicated in the pathogenesis of co- and multi-morbid conditions to mental health disorders. Diet quality is a potential mechanism of action that can exacerbate or ameliorate low-grade inflammation. A good quality diet, high in vegetable and fruit intake, wholegrains, fibre and healthy fats ameliorates low-grade inflammation, and therefore represents a promising therapeutic approach, as well as an important element for disease prevention in both children and adolescents.

- dietary intake

- dietary pattern

- macronutrients

- biomarkers

- inflammation

- CRP

- cytokine

- inter-leukin

- children

- adolescent

Note: The following contents are extract from your paper. The entry will be online only after author check and submit it.

1. Introduction

Inflammation is a physiological response to cellular and tissue damage. It is designed to protect the host from bacteria, viruses and infections by eliminating pathogens, promoting cellular repair and restoring homeostatic conditions [1]. However, a prolonged inflammatory state through chronic low-grade inflammation has deleterious effects, including irreparable damage to tissues and organs, and increased risk of disease status [2].

Low-grade inflammation, reflected in the overproduction of acute phase proteins such as C-reactive protein (CRP), pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TFN-α) has been established as a risk factor for several neuropsychiatric disorders [3], including depression [4–7] and schizophrenia [8]. Moreover, low-grade inflammation in children and adolescents has been associated with the development of co- and multi-morbid conditions to mental health pathologies [9–12], including cardiovascular disease [13,14], metabolic syndrome [15], type-II diabetes [16] and obesity [17], therefore making inflammation an important therapeutic target to study, especially for individuals suffering from those conditions.

The potential factors that promote low-grade chronic inflammation are diverse. Stressors such as trauma through adverse childhood experiences, psychosocial stress, as well as modifiable lifestyle sources such as limited physical exercise or smoking are all capable of evoking a deleterious inflammatory response. Increasingly, attention has been given to diet quality as a potential mechanism of action that can exacerbate or ameliorate low-grade inflammation and subsequently influence mental health [18,19]. Certainly, healthy dietary patterns of high quality, such as adherence to a Mediterranean Diet [20], or eating foods such as vegetables and fruit [1], or macro/micronutrients, such as omega-3 poly-unsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) [21] or vitamins C and E [22], respectively, have been shown to reduce systemic inflammation [23,24]. In observational and interventional studies, a higher quality diet, comprised of these nutrients, has been associated with a reduced risk of adverse mental health in both children [25] and adolescents [26,27]. In contrast, the prevailing Western dietary pattern, which is high in refined grains, red meat, refined sugar and saturated fat, elicits a pro-inflammatory response and increasing levels of circulating inflammatory biomarkers [21].

Moreover, it is well established that a healthy diet in childhood and adolescence is crucial for optimal growth and development and for disease prevention [28]. For example, higher vegetable intake in childhood has been associated with a lower risk of developing mental health pathologies later in life [29], such as depression. In addition, a healthy diet can contribute to the prevention of cardio-metabolic multi-morbidities, often seen in adult patients with neuropsychiatric conditions [30]. As such, modifying dietary intake as early as during childhood and adolescence represents a promising therapeutic strategy in order to maintain a regular immune response, and to reduce the risk of adverse mental health disorders and associated co- and multi-morbid conditions later in life.

Former literature reviews in children and adolescents have focused on various aspects of diet and various biomarkers that, however, are not specifically related to the immune system function and response [31–33]. Therefore, to the best of our knowledge this is the first systematic review bringing together the current evidence base from observational and interventional studies investigating associations between dietary intake, nd biological markers of low-grade inflammation, including CRP, IL-6 and TNF-α among others, in both children and adolescents.

2. Discussion

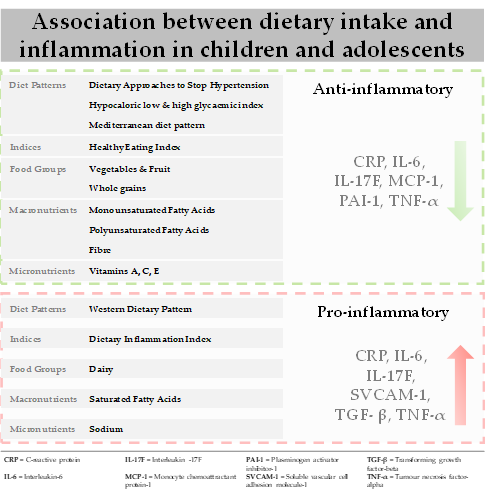

This review provides the first evidence for the association between dietary intake (dietary patterns, food groups, macronutrients and micronutrients) and biological markers of inflammation in children and adolescents. The main results (Figure 1) indicate that adequate adherence to healthful dietary patterns, such as the DASH diet, low glycaemic index diets and the Mediterranean diet are associated with decreased levels of biomarkers, including CRP, IL-6 and TNF-α. Among the individual constituents of these diets, vegetable and fruit intake and wholegrains, as well as healthy fats were associated with a favourable inflammatory response. In contrast, a Western dietary pattern, as well as its separate constituents including saturated fatty acid, elicited a pro-inflammatory response increasing levels of pro-inflammatory biomarkers, such as CRP, IL-6, TNF-α and sVCAM-1. Associations across the studies included in this review were attenuated by gender, as well as the presence of underlying pathologies, independent of dietary intake.

Figure 1. Association between dietary intake and biomarkers of inflammation in children and adolescents.

Traditionally diet–disease relationships have been examined by focusing on nutrients or food groups, which can be limiting. Foods are typically eaten in combination, and nutrients have both synergistic and antagonistic biochemical interactions [90]. More recently, dietary patterns that capture the whole diet, involving the combination of foods and nutrients have been examined [91]. The most examined dietary pattern in this review was the Mediterranean diet and in observational studies conducted in healthy populations adequate to high adherence resulted in decreased levels of pro-inflammatory biomarkers [46,48,52]. Similar results were found for studies examining low glycaemic index diets in obese populations [43–45] and one intervention study in females with metabolic syndrome which examined the DASH diet [41].

The mechanisms by which these healthful dietary patterns affect the inflammatory process are largely underexplored [18]. It has been hypothesised that the protective effect of these patterns may be derived from the anti-inflammatory properties of their constituents [92]. The Mediterranean diet is characterized by high intakes of vegetables, fruit, wholegrains, legumes, nuts, fish and low-fat dairy, and low intakes of red meat and adequate intakes of healthy fats [93]. As such, the diet is rich in antioxidants, folate, and flavonoids which are anti-inflammatory. The high dietary fibre content supports gut health and the growth of microbial species which potentially regulate the inhibition or production of pro-inflammatory chemokines and cytokines [94]. Omega-3 PUFAs, found in high concentration in oily fish such as salmon, have been shown to regulate the immune response by inhibiting the activation of pro-inflammatory pathways and reducing cytokine expression [3]. High-dose eicosapentaenoic acid has been shown to improve cognitive symptoms in Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) youth with low baseline levels [95,96], while research in animal models has demonstrated inflammation-induced reductions in neurogenesis can be prevented through omega-3 PUFAs intake [97]. Lastly, sodium intake has been implicated in the regulation of the immune response [98]. The DASH diet, which is similar to the Mediterranean diet, with a greater focus on minimal red meat and processed foods, also restricts sodium intake [99]. Similar to sodium, the studies included in this review also examined other dietary components with strong anti-inflammatory properties. For example, studies showed that high intakes of vegetables and fruit [59,63–68], and whole-grains [68,72] resulted in lower levels of inflammatory biomarkers, such as CRP, IL-6 and TNF-α. The same was for various micronutrients such as beta-carotene [66] and vitamins C and E [39] all of which are considered to have anti-inflammatory properties [100].

In contrast to healthful dietary patterns, studies that examined the Western dietary pattern, characterised by high amounts of refined grains, red meat, high fat dairy, ultra-processed food intake and trans fatty acids while being low in omega-3 PUFAs [101,102] showed positive associations with pro-inflammatory markers [37,54]. Similarly, in the studies that examined the DII, diets with high inflammatory potential, inducing a higher inflammatory response were positively associated with pro-inflammatory biomarkers in males and females [51,55,57,58]. In terms of separate components comprising these diets, saturated fatty acid intake is known to be a significant pro-inflammatory contributor that stimulates IL-6 secretion, while in contrast high intakes of healthier fats, such as omega-3 PUFAs found in oily fish can inhibit the inflammatory response [103]. Across the studies that examined saturated fatty acids in this review there was evidence for a positive association between saturated fatty acid and CRP, as well as various cytokines, IL-6, sVCAM and sICAM [59].

As demonstrated in this review, the relationship between diet and inflammation is attenuated by a number of different factors [1,104,105]. For example, gender differences were evident across the studies included in this review, however, they were not specific to one particular diet, food group, macro- or micronutrient. Nor where they specific to any inflammatory biomarker. We hypothesize the gender difference is potentially attributable to the influence of hormones. Sex hormones affect immune function, whereby estrogens stimulate auto-immunity and androgens exhibit protective properties [106–109]. Other evidence indicates genetic, epigenetic and environmental factors may also contribute to gender differences; however, no included studies explored these potential associations [109,110]. Furthermore, we acknowledge the heterogeneity in the cohorts of the studies included in this review, and as such some associations could have been confounded by the sample population. A number of studies examined cohorts with underlying pathologies, with overweight/obesity [42–45,50,51,53,70,71,75,81,86], and type-1 diabetes [40,60,82] being the most studied. In overweight and obese populations excess adipose tissue has been linked to an increase in sub-chronic levels of key pro-inflammatory cytokines, mainly CRP, IL-6 and TNF-α [111], and this may prevent or attenuate any potential therapeutic effect exerted by a healthful diet [112]. Taken together, physiologic mechanisms specific to disease state or population may inhibit any beneficial influence of a healthy dietary pattern, potentially explaining the lack of significant associations in the studies discussed in our review [82].

With regards to methodology, it is widely accepted that nutrition epidemiology studies are affected by reporting bias. Imprecision in the measurement of dietary intake is often observed, particularly in children and adolescents, which can cause the over- or under- estimation of the impact of exposure [113–115]. Moreover, the measurement tools themselves are often flawed, for example the KidMed questionnaire, used to evaluate the level of adherence to the Mediterranean diet, has a strong bias toward healthy foods and as such may not adequately capture hidden constituents such as sodium [116]. These methods also do not consider the biological effect of food (intake versus absorption) [117]. More recently, several studies have examined associations between biological markers of dietary intake and pro-inflammatory biomarkers. Using these methods, an inverse association between fatty acid composition in erythrocytes and pro-inflammatory biomarkers (IL-1β and IL-6) has been observed in children and adolescents [118], and higher omega-6/omega-3 PUFAs ratio has been associated with higher levels of inflammation [119] and subsequent adverse mental health effects [120]. These biological, rather than self-reported, dietary measures are a more accurate and reliable way of investigating dietary intake, which should be more often used in future research studies [121].

Lastly, there is currently no consensus regarding the inflammatory biomarkers best used to represent chronic low-grade inflammation in children and adolescents, and biomarker measurement error such as sampling, storage and laboratory errors also cannot be excluded [122]. The majority of the studies in this review used a single static measurement of inflammation, however, inflammatory markers owing to their role in homeostasis and immune response are by nature not static and when measured in the fasting state are recognised as being insensitive, and producing highly variable results [2]. Multiple, non-fasting state measures would provide for more accurate and meaningful outcomes.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/nu13020356