In the past decades, monitoring programs have been developed for healthcare professionals with substance use disorders. We aimed to explore estimates of abstinence and work retention rates after participation in such monitoring programs.

- abstinence

- healthcare professional

- meta-analysis

- work retention

- substance use disorder

- monitoring

1. Introduction

Substance Use Disorders (SUD) are a major health burden, also among healthcare providers, not only affecting their own health, but also their professional image and potentially patient safety[1][2]. Although the prevalence of SUD in healthcare professionals is estimated to be similar to that in the general population (about 10%) [1][3] they more often abuse alcohol and addictive medication, like sedatives and opioids, compared to other SUD patients[4][5].

In the 1970s, the first so-called Physician Health Programs (PHPs) were initiated in the United States. PHPs aim to facilitate early identification and adequate treatment of psychiatric disorders, including SUD, among physicians [6]. Subsequently, health programs were established for other healthcare disciplines and in many more, mainly Western, countries across the globe[7][8]. The content and scope of these health programs vary widely. In the United States (US), professionals are commonly referred to inpatient and/or outpatient treatment in regular care and participate in monitoring provided by the health program[9]. In Europe, some programs mainly provide advice, others provide treatment themselves, and some offer monitoring[7]. A key difference between US health programs and some European programs (e.g., in Norway, Spain, and the United Kingdom (UK)), is that European programs encourage voluntary help seeking by offering free services and have high rates of self-referrals (45–75%)[7]. Additionally, the UK program also guarantees confidentiality by not having any formal links with regulating authorities[10].

Monitoring offers the opportunity to follow the rehabilitation of healthcare professionals with SUD by using biological testing as an objective measure for substance use or abstinence[11]. Monitoring can be started simultaneously with treatment, as well as after successful treatment completion. In addition to biological monitoring of substance use, health programs might also monitor a participants’ fitness to practice at work (by an employer or colleague) or require participation in self-help groups. Health programs usually report outcomes of rehabilitation in terms of abstinence or relapse, return to clinical practice, and/or program completion. A systematic review on rehabilitation outcomes for healthcare professionals found a variety of success rates: abstinence rates of 56% to 94% and work retention rates at the end of follow-up of 74% to 90% [12]. Previous research suggests that this variation in success rates might be influenced by both monitoring elements and participant characteristics[12][1]. Unfortunately, success rates in the systematic review were only presented as ranges per outcome and no thorough examination of the actual data was performed.

So far, there is no meta-analysis performed about success rates of monitoring for healthcare professionals with SUD. Therefore, the current meta-analysis aims to explore success rates of monitoring, using biological testing, for healthcare professionals with SUD, in terms of abstinence and work retention. Furthermore, we explored whether specific monitoring elements and/or participant characteristics explained heterogeneity in success rates across studies.

2. Study Selection, Data Extraction, and Quality Assessment

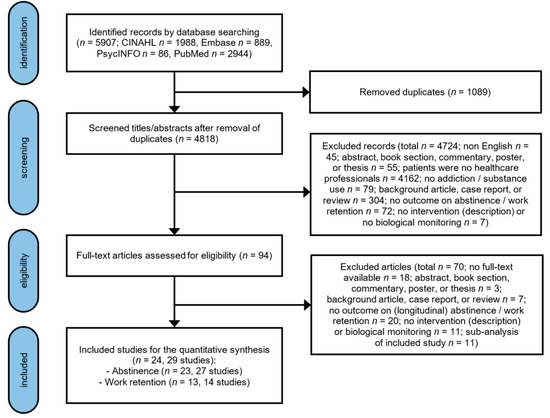

A flow chart of the study selection procedure is provided in Figure 1. First, duplicates were removed, using Rayyan software (Qatar Computing Research Institute, Doha, Qatar, 2017) for citation screening [1]. Next, three authors (P.M.G., S.J.M.v.d.B., and B.A.G.D.) screened 5907 unique titles and abstracts on the selection criteria mentioned above. Discrepancies in the identified eligible records were discussed until consensus was reached. When in doubt, records moved on to the next phase of assessing the eligibility, based on the full-text articles. Full-text assessment of 94 remaining records was performed by two authors (P.M.G. and S.J.M.v.d.B.). Discrepancies were discussed until consensus was reached. This resulted in 29 studies eligible for the meta-analysis, published in 24 articles. Next, data-extraction was performed by one researcher (P.M.G.). The data of each study was documented in Microsoft Excel 2016, which was subsequently checked by a second researcher (S.J.M.v.d.B).

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart of the selection of studies.

Extracted information included study characteristics: name of first author, year of publication, country (state) of first author, design of the study, time frame of the study, number of included subjects, percentage of males, type of healthcare professional, type of substance use, and source of referral. In addition, characteristics of monitoring were summarized: name of the health program, recommended type of treatment, starting moment of monitoring, type of biological testing, monitoring at work, and additional agreements. Finally, the outcomes of monitoring programs were extracted: percentage of abstinence and work retention specified with the (exact or range of) duration of follow-up. Since the information was not always presented in the same manner, we categorized monitoring elements and participant characteristics in order to perform subgroup analyses: program elements (biological, at work, and additional agreements; biological and additional agreements; biological and at work; biological), starting moment of monitoring (before treatment; after treatment; unknown), duration of follow-up (less than 2 years; 2 to 5 years; more than 5 years; other duration), gender (more than 50% males; other or unknown), type of healthcare professional (more than 50% physicians; other or mixed), and type of substance use (more than 50% alcohol; more than 50% opioids; mixed or unknown).

All included studies were assessed on their quality in order to account for study quality in the meta-analysis. The initial assessment was performed by one researcher (P.M.G.), and subsequently checked by a second researcher (S.J.M.v.d.B.). The Health States Quality Index[3] was used to assess study quality. Assessment parameters include a clear definition of the target population and observation period (yes or no), use of diagnostic criteria (diagnostic system or symptom based/not specified), method of case selection (attempting all cases, convenience sampling, or not specified), type of outcome assessment (administered interview, register/case record, or not specified), size of the study area (broad, small, or not specified), and type of prevalence measure (exact follow-up duration, average follow-up duration, or range of follow-up duration). The quality index of each study is calculated as the total quality score of that study divided by the maximum total quality score, see Table A1. The instrument was slightly adjusted for a good fit to our meta-analysis. The higher the score, the higher the study quality. We report our study in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) and the proposal for reporting Meta-analyses of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) were applicable, see Table S1[4][5].

3. Abstinence

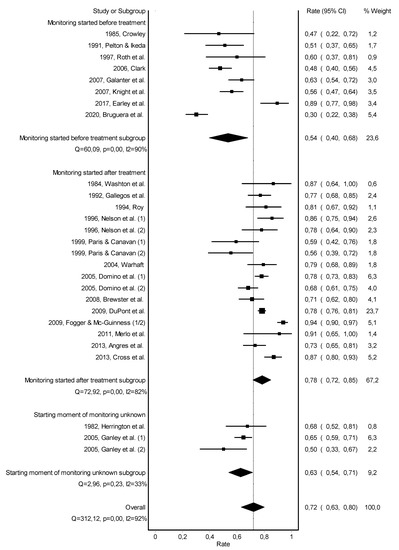

Abstinence rates in the individual studies ranged from 30 to 94% with a substantial heterogeneity across studies (Q = 312.1; p < 0.001; I2 = 92%). The overall pooled abstinence rate across studies was 72% (95%-CI = 63−80%), with a follow-up duration up to 8 years, see Figure 2. When stratified by starting moment of monitoring, the subgroup analysis slightly reduced heterogeneity across studies and showed a higher abstinence rate among studies that started monitoring after treatment completion (79%; 95%-CI = 72–85%; Q = 74.0; p < 0.001; I2 = 80%), compared to studies that started monitoring at treatment initiation (53%; 95%-CI = 40–67%; Q = 60.3; p < 0.001; I2 = 88%).

Figure 2. Forest plot of the pooled abstinence rate—subgroup analysis based on starting moment of monitoring.

Subgroup analyses on the type of monitoring did slightly reduce heterogeneity across studies (Figure A1). Heterogeneity across studies was not significantly reduced by duration of follow-up, gender, type of healthcare professional, and type of substance use (Figure A2, Figure A3, Figure A4 and Figure A5). Risk of bias across studies was visualized in a Doi plot, indicating an asymmetric shape for the pooled abstinence rate (Figure A6). The LFK index was −1.59, also indicating minor publication bias.

4. Work Retention

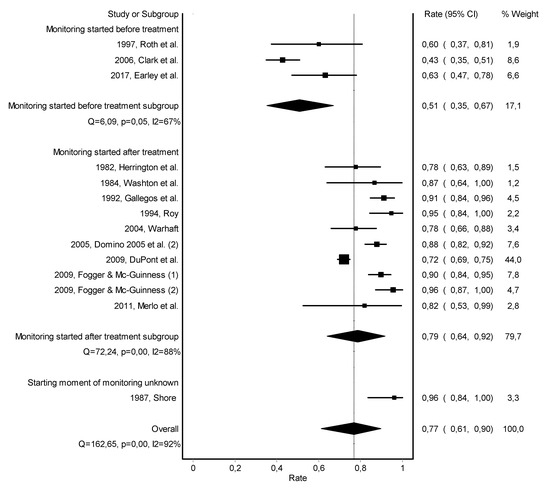

Work retention rates of the individual studies ranged from 43 to 96% with a substantial heterogeneity across studies (Q = 162.7; p < 0.001; I2 = 92%). The overall pooled work retention rate was 77% (95%-CI = 61–90%), with a follow-up duration up to 8 years (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Forest plot of the pooled work retention rate—subgroup analysis based on starting moment of monitoring.

Subgroup analyses on type of monitoring and type of substance use did slightly reduce heterogeneity across studies (Figure A7 and Figure A11). Subgroup analyses on starting moment of monitoring, duration of follow-up, gender, and type of healthcare professional did not significantly reduce heterogeneity across studies (Figure 3, Figure A8, Figure A9 and Figure A10). Risk of bias across studies was visualized in a Doi plot, indicating an asymmetric shape for the pooled work retention rate (Figure A12). The LFK index was −2.70, also indicating major publication bias.

5. Conclusions

Three quarters of the healthcare professionals who engaged in monitoring for SUD remained abstinent and were working at follow-up. There was significant heterogeneity across studies, as well as an indication for major publication bias. The heterogeneity in success rates of monitoring was slightly explained by the starting moment of monitoring, with studies starting monitoring after treatment completion showing higher success rates than studies starting monitoring at treatment initiation. Given the heterogeneity across studies and indication for publication bias, no firm conclusions can be drawn about the effectiveness of monitoring for healthcare professionals with SUD. Future studies should apply controlled comparisons, using more rigorous measurements and substantially long follow-up rates.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jcm10020264

References

- Knight, J.R.; Sanchez, L.T.; Sherritt, L.; Bresnahan, L.R.; Fromson, J.A. Outcomes of a monitoring program for physicians with mental and behavioral health problems. J. Psychiatr. Pract. 2007, 13, 25–32.

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210.

- Barendregt, J.; Doi, S. MetaXL User Guide; EpiGear: Sunrise Beach, Australia, 2016.

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 2009, 339, b2535.

- Stroup, D.F.; Berlin, J.A.; Morton, S.C.; Olkin, I.; Williamson, G.D.; Rennie, D. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: A proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA 2000, 283, 2008–2012, doi:10.1001/jama.283.15.2008.