Bacteriocins are antimicrobial peptides or proteinaceous materials produced by bacteria against pathogens. These molecules have high efficiency and specificity and are equipped with many properties useful in food-related applications, such as food preservatives and additives, as well as biomedical applications, such as serving as alternatives to current antibacterial, antiviral, anti-cancer, and antibiofilm agents. Despite their advantages as alternative therapeutics over existing strategies, several limitations of bacteriocins, such as the high cost of isolation and purification, narrow spectrum of activity, low stability and solubility, and easy enzymatic degradation, need to be improved. Nanomaterials are promising agents in many biological applications. They are widely used in the conjugation or decoration of bacteriocins to augment the activity of bacterioc-ins or reduce problems related to their use in biomedical applications. Therefore, bacteriocins combined with nanomaterials have emerged as promising molecules that can be used in various biomedical applications.

- bacteriocin

- nanomaterial

- biomedical applications

- nanomedicine

- bacteriocin nanoconjugate

Note: The following contents are extract from your paper. The entry will be online only after author check and submit it.

1. Introduction

Bacteriocins are a group of ribosomally synthesized peptides that are secreted extracellularly by various gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria [1], although a majority of bacteriocins reported are produced by the former, especially lactic acid bacteria (LAB) [2,3]. Extensive studies have been carried out on bacteriocins owing to their excellent antibacterial activity, which is closely associated with strain producing species. In addition, bacteriocins have garnered considerable research attention in the field of biomedicine owing to their generally recognized as safe (GRAS) status, and because they are safe for human consumption due to their degradation by gastrointestinal proteases [4]. They are also being modified to improve the antibacterial spectrum. Most of the well-known bacteriocins are produced by gram-positive bacteria, whereas only a few from gram-negative bacteria have been characterized [5]. The activity of these small bacteriocins consisting of cationic molecules (30–60 amino acids) vary throughout the antibacterial spectrum, mainly due to their amphiphilic helices.

Bacteriocins are widely used as natural food preservatives—substances that delay the growth of microorganisms—in the food industry, because they are easily degraded by enzymes produced in the human gastrointestinal tract [4]. The high quality and safety profile of bacteriocins as natural food preservatives is possible without the use of chemical preservatives, which is strictly regulated by governmental agencies, such as the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the United States, owing to their safety issues. Generally, bacteriocins can be directly added to food or incorporated into food during cultivation with the help of bacteriocin-producing bacterial strains. More recently, bacteriocins have gained considerable attention in the healthcare industry as antibacterial and anticancer agents [6]. Some bacteriocins, such as nisin, have shown excellent and specific antibacterial activity against multi-drug resistant (MDR) strains of gram-positive bacteria, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) [7]. Moreover, gram-negative bacteria are naturally resistant to the action of bacteriocins produced by gram-positive bacteria, which are widely explored in foods. It is worthy to note that the bacteriocins produced by gram-positive bacteria can be combined with antibacterial nanoparticles to inhibit the growth of gram-negative bacteria such as P. aeruginosa. In this respect, Au-nisin successfully experimented for the bacterial growth inhibition of E. coli and P. aeruginosa [8]. Currently, researchers are investigating the biomedical properties of bacteriocins in several anticancer studies and have reported promising results [9]. Therefore, researchers are highly interested to use bacteriocins as safe materials in biomedical applications.

Despite their promising advantages, bacteriocins have certain limitations that hinder their applications in the field of biomedicine [10]. These limitations include the following: (i) easy degradation by proteolytic enzymes, (ii) constricted antibacterial spectrum, (iii) requirement of high dosage to kill MDR bacteria, (iv) high production cost, and (v) low natural production yield. Based on these limitations, only three FDA-approved bacteriocins (nisin, pediocin, and Micocin®) are available for food preservation and anti-spoilage processes [11]. The optimization of different production conditions, purification methods, and combinations with other antimicrobial agents or antibiotics has been assessed by various studies to overcome the aforementioned shortcomings in ensuring the broad application of bacteriocins in biomedicine. As adjuvant bioactive materials for bacteriocins, nanomaterials seem highly promising to overcome these challenges [12]. The major reasons for the use of nanomaterials can be attributed to their following characteristics: (i) broad antibacterial spectrum, (ii) stability in physiological solution, (iii) high surface area-to-volume ratio, (iv) easy to synthesize with low production cost, and (v) non-toxic nature at low concentrations. Bacteria are unable to generate rapid resistance against nanomaterials owing to their multi-dimensional approach compared to antibiotics, which targets a single cellular component [13]. Therefore, the combination of bacteriocins and nanomaterials offers new tactics to overcome the limitations posed by the sole use of bacteriocins in biomedical applications.

2. Bacteriocin–Nanomaterial Combination

Nanomaterials have been recently used to potentially overcome such limitations [10,16]. For instance, researchers have already developed bacteriocin–nanomaterial complexes or bacteriocin–nanoconjugates for various biomedical applications of bacteriocins. Multiple advantages for the use of bacteriocin–nanoconjugates have been reported: (i) increased stability for long periods of use, (ii) protection from proteolytic enzyme degradation, and (iii) synergistic activity. The potential applicability of bacteriocin–nanoconjugates with different nanomaterials has been described in following sections.

2.1. Liposomes

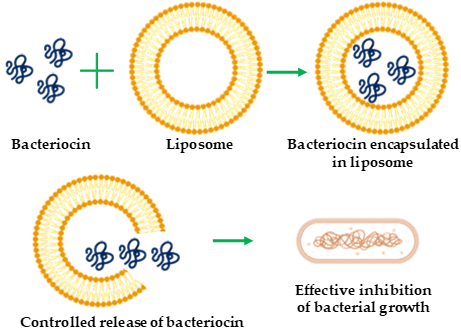

Liposomes are spherical vesicles comprising single or multiple phospholipid bilayer membranes [43]. They are non-toxic and biodegradable agents as well as suitable encapsulating materials for both hydrophilic and hydrophobic substances. The size scale of liposomes varies from micrometers to nanometers, generated via sonication or functionalization [44]. Nano-sized liposomes—called nano-liposomes—are promising vehicles for the encapsulation and delivery of different bioactive compounds such as enzymes, vitamins, and food additives, as well as the delivery of therapeutic bacteriocins to target cells [16]. Liposome encapsulation protects bacteriocins (Figure 1) from degradation caused by physicochemical environment or protease action [45], susceptibility to which is a major limitation of bacteriocins. Various studies addressing the protection of bacteriocins from protease degradation have been reported [46,47]. Liposome encapsulation also confers other advantages, such as improved stability, reduced doses in therapeutic applications, and enhanced antibacterial spectrum [10,16]. Taylor et al. [48] showed that liposomes consisting of distearoylphosphatidylcholine (PC) and distearoylphosphatidylglycerol (PG) with trapped nisin can retain approximately 70–90% of the incorporated nisin with high stability under alkaline pH and elevated temperatures (25–75 °C). Similarly, Pinilla et al. [49] showed that nanoliposomes co-encapsulated with nisin and garlic extracts became broad-spectrum antimicrobial agents against L. monocytogenes, Salmonella enteritidis, E. coli, and S. aureus. This expanded antibacterial spectrum has shown that bacteriocin could be modulated to be active on both gram-positive and -negative bacteria. The successful application of liposome-encapsulated bacteriocins depends on appropriate phospholipid bacteriocin combinations, the avoidance of adverse liposome–bacteriocin interactions, and high purity of starting materials. Such liposome-encapsulated bacteriocins have been mainly used as antibacterial substances [49] and have food-related [50] applications.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of bacteriocin encapsulation with liposome for antibacterial activity.

2.2. Chitosan

Chitosan is another type of nanoparticle, which is widely used with bacteriocins in various biomedical applications. Chitosan is an ideal candidate for these applications due to its non-toxic, biocompatible, and biodegradable nature [51]. Moreover, its antibacterial and anticancer activity coupled with its ability to deliver drugs to their targets is well researched [51,52]. Many researchers have used chitosan with bacteriocins to obtain a material showing synergistic antibacterial activity. For instance, Namasivayam et al. [53] reported synergistic antibacterial activity of chitosan–nanoconjugates loaded with bacteriocins against Listeria monocytogenes; the activity levels of these nanoconjugates were higher than those of free bacteriocins. In another study, Alireza Alishahi [54] demonstrated excellent antibacterial activity by chitosan nanoparticles loaded with nisin against E. coli and S. aureus. Moreover, nanocomposite comprised of bacteriocin and chitosan have also been used in food packaging (Figure 2). For example, Divsalar et al. [55] formed a composite film containing chitosan, cellulose, and nisin for use in packaging of ultra-filtered cheese. The composite film showed better food packaging properties than chitosan and cellulose film alone. Similar studies have been conducted using bacteriocin–chitosan nanocomposites for drug delivery [56].

Figure 2. Schematic representation of improved food packaging with bacteriocin.

2.3. Metallic Nanoparticles

Currently, metallic nanoparticles such as zinc, copper, silver, and gold are being studied not only for their antibacterial activity, but also for their different potential biomedical applications [12,13,57–60]. The extensive use of these nanoparticles can be attributed to their large surface area along with their positive charge, which can interact with negatively charged bacterial cell surfaces [11]. Among bacteriocin–metallic nanocomposites, Ag and Au nanoparticles are the most studied materials, showing synergistic effects in biomedical applications [10,16]. The antibacterial activity of Ag and Au nanoparticles is well reported [12]. Therefore, it is easy to understand the rationale behind the combination of bacteriocins with Ag/Au nanoparticles. This combination will not only enlarge the antibacterial spectrum, but also reduce the toxicity of nanoparticles. In this respect, Sharma et al. [32] reported enterocin-coated silver nanoparticles, which not only showed broad-spectrum inhibition against various food-borne pathogenic bacteria but also admirable non-toxicity to red blood cells, emphasizing its biocompatible nature. Pandit et al. [61] also reported the antibacterial activity of Ag–nisin nanoconjugates against Listeria monocytogenes, S. aureus, Pseudomonas fluorescens, Aspergillus niger, and Fusarium moniliforme associated with food spoilage. These results reveal the potential uses of bacteriocin–metal nanoconjugates in food packaging. Preet et al. [62] also reported the use of Au nanoparticles in other biomedical applications such as the co-delivery of nisin and doxorubicin to treat murine skin cancer.

2.4. Nanofibers

Nanofiber technology is known for its application in wound care formulations, wherein nanofibers are loaded with antimicrobials and hemostatic agents for wound healing. Bacteriocins can also be loaded with nanofibers for the same purpose [10]. The large surface area, high physical stability, and excellent encapsulation ability along with small pore size have made nanofibers the perfect nanocarriers for target-specific drug delivery [63]. Nanofiber-based bacteriocin–nanoconjugates are used as antibacterial and antiviral substances. In a recent study, Torres et al. [64] explored the efficacy of a subtilosin-loaded poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVOH) nanofiber as an antiviral agent against Herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1). Subtilosin with 200 µg mL-1 showed a remarkable virucidal and antiviral activity against HSV-1, although the mechanistic action has not been elucidated. The PVOH-based subtilosin nanofibers with a width of 278 nm has retained subtilosin’s antibacterial efficacy, increased the loading potential of subtilosin (2.4 mg subtilosin/g of fiber) with loading efficiency of 31.6%, and demonstrated non-toxicity to human epidermal tissues. Electrospinning-based bacteriocin-nanofibers have also been studied as a drug delivery system. For instance, Ahire et al. [65] determined the activity of nisin incorporated into nanofibers prepared from poly(D,L-lactide) (PDLLA) and poly (ethylene oxide) (PEO). This combination has shown enhanced antibiofilm activity against MRSA than that by nisin alone.

2.5. Other Nanoplatforms

Researchers are attempting to use nanoplatforms other than liposomes, chitosan, metallic nanoparticles, or nanofibers to encapsulate or conjugate bacteriocins with nanomaterials. Niaz et al. [66] used bacteriocin-loaded nanovesicles due to their excellent antimicrobial and antibiofilm activities against food-borne pathogens. Similarly, Breukink et al. [67] evaluated the binding of nisin Z to bilayer lipid vesicles. Yadav et al. [68] assessed the interaction between nisin and vesicles synthesized using different phospholipids. Another example of nanoplatforms is solid–lipid nanoparticles (SLN), which have been used to encapsulate bacteriocins for various biomedical applications [10]. Bacteriocin-loaded SLN not only protect bacteriocins from degradation but also extend their antibacterial activity for a long period of time [69]. Phytoglycogen nanoparticles are another type of nanomaterial used to carry bacteriocins to the target site [70].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/pharmaceutics13010086