Interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) are chronic irreversible pulmonary conditions with significant morbidity and mortality. Diagnostic approaches to ILDs are complex and multifactorial. Effective therapeutic interventions are continuously investigated and explored with substantial progress, thanks to advances in basic understanding and translational efforts. Extracellular vesicles (EVs) offer a new paradigm in diagnosis and treatment.

- : extracellular vesicles

- exosomes

- pathogenesis

1. Introduction

Interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) are a wide spectrum of diffuse parenchymal pulmonary conditions indicated by inflammatory changes in the alveoli. ILDs may present either idiopathically or by a sequela to preexisting comorbidities such as connective tissue, autoimmune diseases, or secondary to biological, chemical, or fine particle exposure [1][2]. The American Thoracic Society (ATS) and European Respiratory Society (ERS) designated the term idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP) for ILDs of unknown etiologies [3]. IIPs are further subdivided as major, rare, and unclassified IIP [4][5][6]. The natural course of ILDs is characterized by chronic, progressive, and irreversible fibrosis with significant morbidity and mortality [6][7][8][9]. While the management of non-idiopathic ILDs relies on addressing the underlying cause of disease, the standard treatment approaches for IIP include antifibrotic therapy or lung transplantation [10][11][12][13][14]. Although current treatments provide significant morbidity and mortality benefits [15], they are not curative. Extensive research in the pathogenesis of lung fibroproliferation has opened new avenues of therapeutic intervention. ILDs continue to levy significant burdens on morbidity, mortality, and healthcare expenditure worldwide [16][17][18][19]. Further understanding of the underlying pathogenic mechanisms is essential for more effective antifibrotic treatment approaches. A new and promising avenue of investigation relates to the role of extracellular vesicles (EVs) in parenchymal lung injury and interstitial fibrosis. The role of EVs in the pathogenesis of nonmalignant chronic respiratory conditions has been extensively described in ILDs [20][21][22], asthma [23][24], chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD) [25][26][27], and pulmonary hypertension [28][29]. These studies provide an evidence base for the clinical translation of EVs in ILD diagnosis and the utilization of therapeutic EVs for treatment.

EVs are easily quantifiable and have features amenable to direct (i.e., as treatments) and indirect (i.e., as diagnostic tools) therapeutic applications. These include stability, cargo transfer, and direct regulation of disease pathogenesis. The current gold standard of ILDs diagnosis is invasive procedures such as transbronchial cryobiopsy through bronchoscopy or surgical lung biopsy [30]. These approaches are associated with an increased risk of procedural complications and clinical intolerability, particularly in patients with respiratory insufficiency [31][32]. As a result, noninvasive and reliable biomarkers for ILDs are needed for more effective clinical management and care. Additionally, EVs can also be used to monitor disease progression and response to treatment. The physiologic and pathogenic roles of EVs suggests their utility as a therapeutic platform in the restoration of organ homeostasis and reversal of tissue damage. Indeed, the steady migration of cells to EV therapy in regenerative medicine is primarily due to the versatility of these particles over traditional cell transplantation therapy [33][34][35]. The advancement of EV cargo content engineering renders EVs more versatile and customizable to several disease types [36]. Despite significant progress, some limitations have limited the transition of EVs to clinical studies [37]. Therefore, this review focuses on the current understanding of the molecular pathways that drive ILDs and the role of EVs in disease progression. We further discuss the applicability of EV translation in the context of biomarker development and EV therapy.

2. Extracellular Vesicles

Extracellular vesicles are lipid bilayer nanoparticles secreted by nearly all cell types and comprise several classes of particles delineated by size and pathway of biogenesis. For instance, exosomes are smaller (30-150 nm) particles produced through the late endosome with selective packaging of cargo. Ectosomes (e.g., microvesicles, apoptosomes, etc.) (100 nm–1 µm) are passively shed from the plasma membrane. However, evidence from the cancer biology and hypersensitivity models demonstrates that ectosome content will change based on different cell stimuli (i.e., stress, antigen exposure, etc.) [38]. Whether this is a reflection of the internal contents of the cell (in response to stimuli) or evidence of bona fide cargo-sorting remains to be verified. However, a recent report indicated that pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) can be sorted into hepatocellular carcinoma ectosomes through the sumoylation process [39]. EVs also carry a plethora of signaling mediators, including several classes of non-coding RNAs (micro-RNAs, long noncoding RNAs, Piwi RNAs, etc.), proteins (growth factors, transcription factors, etc.), and lipids [40][41]. The discovery of extracellular vesicles [42][43] and their biological roles appears to be significant in a variety of human diseases, namely in chronic conditions such as pulmonary disease, cancer, diabetes, heart diseases, Alzheimer’s disease, kidney failure, liver cirrhosis, etc. [44][45][46][47][48][49]. Primarily, the demonstration of EVs facilitating intercellular communication has created a paradigm shift in our understanding of disease pathogenesis [50]. It offers novel tools that aid in the fundamental understanding of basic disease pathogenesis and the development of novel diagnostic and therapeutic platforms [51]. EVs play essential functional roles in maintaining tissue/organ homeostasis during normal development [52][53] and also in disease progression, including tissue damage, fibrosis, and metastasis [54][55][56]. The biological functions of EVs rely on signal transduction of EV-associated cargo molecules, which alter the transcriptome and epigenome of recipient cells. These EVs mediate communication and phenotypic change within and between tissues.

3. EVs in ILD Pathogenesis

The key cellular players in ILD pathogenesis include alveolar epithelial cells, lung fibroblasts, leukocytes, and endothelial cells [57]. Crosstalk between these cell types in the context of the injured lung microenvironment is mediated, at least in part, by EVs [58]. For instance, alveolar macrophage-, neutrophil-, and epithelial cell-derived EVs sampled from bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) mediate the acute and resolution phases of acute lung injury through the transfer of proinflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IL-6, and IL1-β [59][60][61]. Indeed, in EVs isolated from human healthy volunteers, BALF carries MHC I and II, CD54, CD63, and the co-stimulatory molecule CD86, implicating their potential roles in immune regulation [62]. Similar studies in other chronic respiratory conditions (e.g., asthma, COPD, and lung cancer) confirm the disease-propagating role of EVs [63][64]. These findings highlight the importance of EVs in lung microenvironment signaling. Furthermore, through universal inflammatory and fibrotic processes, EVs are likely to play similarly critical roles in ILDs.

3.1. EVs in Nonidiopathic Interstitial Lung Diseases

Nonidiopathic ILDs are defined as ILDs with known causes, such as connective tissue disorders, toxic environmental exposures, or chronic inflammatory lung diseases such as sarcoidosis [65]. The implication of EVs in non-idiopathic ILDs is gaining increasing interest. A higher quantity of EV-associated proteins, called tissue factor (TF), were found in microvesicles (MVs, size ranged 0.05-1μm) in the BALF of pulmonary fibrosis cases (4 known cause ILDs and 15 IIP patients). EV-bound tissue factor (TF) activity was associated with disease severity, highlighting the possible causal relationship between pathogenic MVs and lung damage [66]. TF-bearing MVs stimulated reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in human lung epithelial cell lines (A549 and NHBEC), suggesting that these MVs propagate injury (and fibrosis development) across the pulmonary epithelium.

A few studies of pulmonary sarcoidosis, a chronic inflammatory ILD, showed that sarcoidosis patients had a higher EV-burden in their BALF [67][68]. These EVs retained proinflammatory properties as demonstrated by their capacity to induce interferon-γ (IFNγ) and interleukin IL-13 production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and IL-8 from epithelial cells [67]. Others also reported that BALF-derived EVs from sarcoidosis patients stimulated monocytes to release IL-1β, IL-6, CCL2, and Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) [69]. These proinflammatory mediators promote lung inflammation that leads to fibrosis progression in patients with sarcoidosis. Therefore, EVs carry specific cargoes that can induce inflammatory responses in both immune and lung epithelial cells. Further characterization of these cargoes and their involvement in lung fibroproliferation is needed to understand the contribution of EVs to ILD pathogenesis and prognosis.

3.2. EVs in Idiopathic Interstitial Lung Diseases

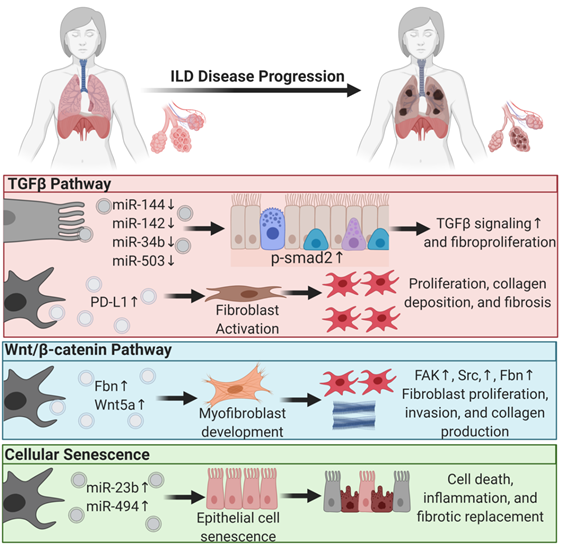

The most common interstitial lung disease in this category is idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). Single-cell RNA-sequencing of human and mouse lungs indicated that many cell types in the lungs are involved in IPF pathogenesis [70][71]. Most of those cells secrete EVs that drive lung fibroproliferative processes through activation of profibrotic signaling pathways such as transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) signaling, wingless N-type (Wnt)/β-catenin signaling, and cellular senescence.

EVs mediate lung fibroproliferation through the activation of TGFβ signaling, a well-established profibrotic pathway. It has been shown that TGFβ stimulates human and mouse fibroblasts to secrete EVs enriched in Program Death Ligand-1 (PD-L1) protein [72]. EV-associated PD-L1 further promotes lung fibroblast activation, proliferation, and paracrine-mediated suppression of T cell proliferation [72]. We and others have shown that EV-associated miRNAs from injured tissue have lower levels of antifibrotic TGFβ -regulating miRs. In particular, miR-144-3p, miR-142-3p miR-34-b, and miR-503-5p are depleted in injured lung epithelial cell-derived EVs. MiR-144-3p and miR-142-3p also inhibit phosphorylation of the SMAD2 protein in a mouse bleomycin-induced lung injury model [21]. Moreover, macrophage-derived EVs downregulate the expression of TGFβ receptor 1 (TGFβ-R1) and profibrotic genes in lung epithelial cells and lung fibroblasts through miR-142-3p [73]. Others showed that IL-1β activation on lung fibroblasts stimulated EV-associated prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) production. PGE2 in the EVs can downregulate TGFβ signaling on lung fibroblasts through autocrine and paracrine effects [74]. In summary, EVs carry proteins and microRNAs that modulate TGFβ signaling, a major pathway of lung fibroproliferation.

Another major profibrotic pathway modulated by EVs is the Wnt signaling pathway. Lung-derived EVs following bleomycin injury are enriched in WNT5A, a noncanonical Wnt ligand [75]. Exposing healthy lung fibroblasts to WNT5A triggered fibroblast activation and proliferation, leading to collagen production [75]. Similarly, exposing lung fibroblasts to TGFβ also induced WNT5A and promoted fibroblast activation and fibrotic expansion. Another study showed that EVs derived from lung fibroblasts of IPF patients were enriched in fibronectin (FN), a protein that accumulates in lung fibrotic tissue and increases fibroblast invasiveness and lung fibro proliferation through focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and Src family kinases activation. Others have demonstrated that Wnt activation further induces FN expression [76].

Another principal driving pathway in lung fibrosis is cellular senescence [77][78]. The involvement of EVs in other chronic lung diseases such as COPD and lung cancer through cellular senescence was reviewed previously [79]. In ILDs, one study showed that IPF fibroblast EV-associated miR-23b-3p and miR-494-3p induced human bronchial epithelial cells= senescence by suppressing SIRT3 expression, mitochondrial damage in epithelial cells, and senescence [80]. We have shown that EVs from human IPF lungs and bleomycin-injured mouse lungs had lower levels of antifibrotic miRNAs such as miR-144-3p, miR-142-3p, miR-34-b, and miR-503-5p that regulate cellular senescence, suggesting that EVs from diseased states are prosenescent and profibrotic.

In summary, EVs play a significant role in ILD progression and, in the diseased state, drive lung fibroproliferative processes by activating pathogenic pathways in healthy tissue (Figure 1). This suggests that EVs from patient samples can serve as diagnostic tools and that diseased tissue may be responsive to EV therapy. The former supports the role of EVs as biomarkers, and the latter supports their application in therapy.

Figure 1. Extracellular vesicles regulate profibrotic signaling pathways in interstitial lung disease pathogenesis. Major profibrotic pathways are regulated by extracellular vesicles’ (EVs) cargo molecules in driving the principal pathways of lung fibroproliferative diseases. Arrows pointing up reflect upregulation, and arrows pointing down signify downregulation.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/diagnostics11010087

References

- Lederer, D.J.; Martinez, F.J. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1811–1823, doi:10.1056/NEJMra1705751.

- Antin-Ozerkis, D.; Hinchcliff, M. Connective Tissue Disease-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease: Evaluation and Manage-ment. Clin. Chest Med. 2019, 40, 617–636, doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2019.05.008.

- Gandham, S.; Su, X.; Wood, J.; Nocera, A.L.; Alli, S.C.; Milane, L.; Zimmerman, A.; Amiji, M.; Ivanov, A.R. Technologies and Standardization in Research on Extracellular Vesicles. Trends Biotechnol. 2020, 38, 1066–1098, doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2020.05.012.

- Travis, W.D.; Costabel, U.; Hansell, D.M.; King, T.E.; Lynch, D.A.; Nicholson, A.G.; Ryerson, C.J.; Ryu, J.H.; Selman, M.; Wells, A.U.; et al. An Official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Statement: Update of the Internation-al Multidisciplinary Classification of the Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 188, 733–748, doi:10.1164/rccm.201308-1483ST.

- Guler, S.A.; Ellison, K.; Algamdi, M.; Collard, H.R.; Ryerson, C.J. Heterogeneity in Unclassifiable Interstitial Lung Disease. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2018, 15, 854–863, doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.201801-067OC.

- Ryerson, C.J.; Urbania, T.H.; Richeldi, L.; Mooney, J.J.; Lee, J.S.; Jones, K.D.; Elicker, B.M.; Koth, L.L.; King, T.E., Jr.; Wolters, P.J.; et al. Prevalence and prognosis of unclassifiable interstitial lung disease. Eur. Respir. J. 2013, 42, 750–757, doi:10.1183/09031936.00131912.

- Khor, Y.H.; Ng, Y.; Barnes, H.; Goh, N.S.L.; McDonald, C.F.; Holland, A.E. Prognosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with-out anti-fibrotic therapy: A systematic review. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2020, 29, doi:10.1183/16000617.0158-2019.

- Dhooria, S.; Agarwal, R.; Sehgal, I.S.; Prasad, K.T.; Garg, M.; Bal, A.; Aggarwal, A.N.; Behera, D. Spectrum of interstitial lung diseases at a tertiary center in a developing country: A study of 803 subjects. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191938, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0191938.

- Ryerson, C.J.; Corte, T.J.; Lee, J.S.; Richeldi, L.; Walsh, S.L.F.; Myers, J.L.; Behr, J.; Cottin, V.; Danoff, S.K.; Flaherty, K.R.; et al. A Standardized Diagnostic Ontology for Fibrotic Interstitial Lung Disease. An International Working Group Perspective. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 196, 1249–1254, doi:10.1164/rccm.201702-0400PP.

- Distler, O.; Highland, K.B.; Gahlemann, M.; Azuma, A.; Fischer, A.; Mayes, M.D.; Raghu, G.; Sauter, W.; Girard, M.; Alves, M.; et al. Nintedanib for Systemic Sclerosis-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 2518–2528, doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1903076.

- Wells, A.U.; Flaherty, K.R.; Brown, K.K.; Inoue, Y.; Devaraj, A.; Richeldi, L.; Moua, T.; Crestani, B.; Wuyts, W.A.; Stowasser, S.; et al. Nintedanib in patients with progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases-subgroup analyses by interstitial lung dis-ease diagnosis in the INBUILD trial: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 453–460, doi:10.1016/s2213-2600(20)30036-9.

- De Sadeleer, L.J.; Verleden, S.E.; Vos, R.; Van Raemdonck, D.; Verleden, G.M. Advances in lung transplantation for intersti-tial lung diseases. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2020, 26, 518–525, doi:10.1097/mcp.0000000000000690.

- Sakamoto, S.; Kataoka, K.; Kondo, Y.; Kato, M.; Okamoto, M.; Mukae, H.; Bando, M.; Suda, T.; Yatera, K.; Tanino, Y.; et al. Pirfenidone plus inhaled N-acetylcysteine for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: A randomised trial. Eur. Respir. J. 2020, doi:10.1183/13993003.00348-2020.

- Flaherty, K.R.; Wells, A.U.; Cottin, V.; Devaraj, A.; Walsh, S.L.F.; Inoue, Y.; Richeldi, L.; Kolb, M.; Tetzlaff, K.; Stowasser, S.; et al. Nintedanib in Progressive Fibrosing Interstitial Lung Diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1718–1727, doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1908681.

- Nathan, S.D.; Albera, C.; Bradford, W.Z.; Costabel, U.; Glaspole, I.; Glassberg, M.K.; Kardatzke, D.R.; Daigl, M.; Kirchgaess-ler, K.-U.; Lancaster, L.H.; et al. Effect of pirfenidone on mortality: Pooled analyses and meta-analyses of clinical trials in idi-opathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lancet Respir. Med. 2017, 5, 33–41, doi:10.1016/S2213-2600(16)30326-5.

- Rivera-Ortega, P.; Molina-Molina, M. Interstitial Lung Diseases in Developing Countries. Ann. Glob. Health 2019, 85, doi:10.5334/aogh.2414.

- Frank, A.L.; Kreuter, M.; Schwarzkopf, L. Economic burden of incident interstitial lung disease (ILD) and the impact of comorbidity on costs of care. Respir. Med. 2019, 152, 25–31, doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2019.04.009.

- Antoniou, K.; Kamekis, A.; Symvoulakis, E.K.; Kokosi, M.; Swigris, J.J. Burden of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis on patients’ emotional well being and quality of life: A literature review. Curr. Opin. Pulm. Med. 2020, 26, 457–463, doi:10.1097/mcp.0000000000000703.

- Olson, A.L.; Maher, T.M.; Acciai, V.; Mounir, B.; Quaresma, M.; Zouad-Lejour, L.; Wells, C.D.; De Loureiro, L. Healthcare Resources Utilization and Costs of Patients with Non-IPF Progressive Fibrosing Interstitial Lung Disease Based on Insurance Claims in the USA. Adv. Ther. 2020, 37, 3292–3298, doi:10.1007/s12325-020-01380-4.

- Chanda, D.; Otoupalova, E.; Hough, K.P.; Locy, M.L.; Bernard, K.; Deshane, J.S.; Sanderson, R.D.; Mobley, J.A.; Thannickal, V.J. Fibronectin on the Surface of Extracellular Vesicles Mediates Fibroblast Invasion. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2019, 60, 279–288, doi:10.1165/rcmb.2018-0062OC.

- Parimon, T.; Yao, C.; Habiel, D.M.; Ge, L.; Bora, S.A.; Brauer, R.; Evans, C.M.; Xie, T.; Alonso-Valenteen, F.; Medina-Kauwe, L.K.; et al. Syndecan-1 promotes lung fibrosis by regulating epithelial reprogramming through extracellular vesicles. JCI In-sight 2019, 5, doi:10.1172/jci.insight.129359.

- Worthington, E.N.; Hagood, J.S. Therapeutic Use of Extracellular Vesicles for Acute and Chronic Lung Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2318, doi:10.3390/ijms21072318.

- Eltom, S.; Dale, N.; Raemdonck, K.R.; Stevenson, C.S.; Snelgrove, R.J.; Sacitharan, P.K.; Recchi, C.; Wavre-Shapton, S.; McAuley, D.F.; O’Kane, C.; et al. Respiratory infections cause the release of extracellular vesicles: Implications in exacerbation of asthma/COPD. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e101087, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0101087.

- Mohan, A.; Agarwal, S.; Clauss, M.; Britt, N.S.; Dhillon, N.K. Extracellular vesicles: Novel communicators in lung diseases. Respir. Res. 2020, 21, 175, doi:10.1186/s12931-020-01423-y.

- Feller, D.; Kun, J.; Ruzsics, I.; Rapp, J.; Sarosi, V.; Kvell, K.; Helyes, Z.; Pongracz, J.E. Cigarette Smoke-Induced Pulmonary Inflammation Becomes Systemic by Circulating Extracellular Vesicles Containing Wnt5a and Inflammatory Cytokines. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 1724, doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.01724.

- Fujita, Y.; Araya, J.; Ito, S.; Kobayashi, K.; Kosaka, N.; Yoshioka, Y.; Kadota, T.; Hara, H.; Kuwano, K.; Ochiya, T. Suppres-sion of autophagy by extracellular vesicles promotes myofibroblast differentiation in COPD pathogenesis. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 28388, doi:10.3402/jev.v4.28388.

- Wilkinson, T. Understanding disease mechanisms at the nanoscale: Endothelial apoptosis and microparticles in COPD. Thor-ax 2016, 71, 1078–1079, doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-208993.

- Chen, T.; Raj, J.U. Extracellular Vesicles, MicroRNAs, and Pulmonary Hypertension; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 71–77.

- Khandagale, A.; Åberg, M.; Wikström, G.; Lind, S.B.; Shevchenko, G.; Björklund, E.; Siegbahn, A.; Christersson, C. Role of Extracellular Vesicles in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2020, 40, 2293–2309, doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.314152.

- Zaizen, Y.; Kohashi, Y.; Kuroda, K.; Tabata, K.; Kitamura, Y.; Hebisawa, A.; Saito, Y.; Fukuoka, J. Concordance between sequential transbronchial lung cryobiopsy and surgical lung biopsy in patients with diffuse interstitial lung disease. Diagn. Pathol. 2019, 14, 131, doi:10.1186/s13000-019-0908-z.

- Chami, H.A.; Diaz-Mendoza, J.; Chua, A.; Duggal, A.; Jenkins, A.R.; Knight, S.; Patolia, S.; Tamae-Kakazu, M.; Raghu, G.; Wilson, K.C. Transbronchial Biopsy and Cryobiopsy in the Diagnosis of Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis among Patients with Interstitial Lung Disease. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2020, doi:10.1513/AnnalsATS.202005-421OC.

- Raghu, G.; Remy-Jardin, M.; Myers, J.L.; Richeldi, L.; Ryerson, C.J.; Lederer, D.J.; Behr, J.; Cottin, V.; Danoff, S.K.; Morell, F.; et al. Diagnosis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 198, e44–e68, doi:10.1164/rccm.201807-1255ST.

- Lener, T.; Gimona, M.; Aigner, L.; Börger, V.; Buzas, E.; Camussi, G.; Chaput, N.; Chatterjee, D.; Court, F.A.; Del Portillo, H.A.; et al. Applying extracellular vesicles based therapeutics in clinical trials—an ISEV position paper. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 30087–30087, doi:10.3402/jev.v4.30087.

- Popowski, K.; Lutz, H.; Hu, S.; George, A.; Dinh, P.-U.; Cheng, K. Exosome therapeutics for lung regenerative medicine. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2020, 9, 1785161, doi:10.1080/20013078.2020.1785161.

- Romano, M.; Zendrini, A.; Paolini, L.; Busatto, S.; Berardi, A.C.; Bergese, P.; Radeghieri, A. 2 - Extracellular vesicles in regen-erative medicine. In Nanomaterials for Theranostics and Tissue Engineering; Rossi, F., Rainer, A., Eds.; Elsevier: 2020; pp. 29–58, doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-817838-6.00002-4.

- Murphy, D.E.; de Jong, O.G.; Brouwer, M.; Wood, M.J.; Lavieu, G.; Schiffelers, R.M.; Vader, P. Extracellular vesicle-based therapeutics: Natural versus engineered targeting and trafficking. Exp. Mol. Med. 2019, 51, 1–12, doi:10.1038/s12276-019-0223-5.

- Wiklander, O.P.B.; Brennan, M.Á.; Lötvall, J.; Breakefield, X.O.; EL Andaloussi, S. Advances in therapeutic applications of extracellular vesicles. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019, 11, eaav8521.

- Jimenez, J.J.; Jy, W.; Mauro, L.M.; Soderland, C.; Horstman, L.L.; Ahn, Y.S. Endothelial cells release phenotypically and quantitatively distinct microparticles in activation and apoptosis. Thromb. Res. 2003, 109, 175c180, doi:10.1016/S0049-3848(03)00064-1.

- Hou, P.-P.; Luo, L.-J.; Chen, H.-Z.; Chen, Q.-T.; Bian, X.-L.; Wu, S.-F.; Zhou, J.-X.; Zhao, W.-X.; Liu, J.-M.; Wang, X.-M.; et al. Ectosomal PKM2 Promotes HCC by Inducing Macrophage Differentiation and Remodeling the Tumor Microenvironment. Mol. Cell 2020, 78, 1192–1206, doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2020.05.004.

- Yokoi, A.; Villar-Prados, A.; Oliphint, P.A.; Zhang, J.; Song, X.; De Hoff, P.; Morey, R.; Liu, J.; Roszik, J.; Clise-Dwyer, K.; et al. Mechanisms of nuclear content loading to exosomes. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax8849.

- Jeppesen, D.K.; Fenix, A.M.; Franklin, J.L.; Higginbotham, J.N.; Zhang, Q.; Zimmerman, L.J.; Liebler, D.C.; Ping, J.; Liu, Q.; Evans, R.; et al. Reassessment of Exosome Composition. Cell 2019, 177, 428–445, doi:10.1016/j.cell.2019.02.029.

- Pan, B.-T.; Johnstone, R.M. Fate of the transferrin receptor during maturation of sheep reticulocytes in vitro: Selective exter-nalization of the receptor. Cell 1983, 33, 967–978, doi:10.1016/0092-8674(83)90040-5.

- Harding, C.; Stahl, P. Transferrin recycling in reticulocytes: pH and iron are important determinants of ligand binding and processing. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1983, 113, 650–658, doi:10.1016/0006-291X(83)91776-X.

- Shah, R.; Patel, T.; Freedman, J.E. Circulating Extracellular Vesicles in Human Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 958–966, doi:10.1056/NEJMra1704286.

- Jansen, F.; Nickenig, G.; Werner, N. Extracellular Vesicles in Cardiovascular Disease: Potential Applications in Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Epidemiology. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 1649–1657, doi:10.1161/circresaha.117.310752.

- McVey, M.J.; Maishan, M.; Blokland, K.E.C.; Bartlett, N.; Kuebler, W.M. Extracellular vesicles in lung health, disease, and therapy. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2019, 316, L977-L989, doi:10.1152/ajplung.00546.2018.

- Minciacchi, V.R.; Freeman, M.R.; Di Vizio, D. Extracellular vesicles in cancer: Exosomes, microvesicles and the emerging role of large oncosomes. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2015, 40, 41–51, doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2015.02.010.

- Szabo, G.; Momen-Heravi, F. Extracellular vesicles in liver disease and potential as biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 455–466, doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2017.71.

- Yáñez-Mó, M.; Siljander, P.R.M.; Andreu, Z.; Zavec, A.B.; Borràs, F.E.; Buzas, E.I.; Buzas, K.; Casal, E.; Cappello, F.; Car-valho, J.; et al. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2015, 4, 27066–27066, doi:10.3402/jev.v4.27066.

- Valadi, H.; Ekström, K.; Bossios, A.; Sjöstrand, M.; Lee, J.J.; Lötvall, J.O. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and mi-croRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 654–659, doi:10.1038/ncb1596.

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science 2020, 367, eaau6977.

- Cruz, L.; Romero, J.A.A.; Iglesia, R.P.; Lopes, M.H. Extracellular Vesicles: Decoding a New Language for Cellular Commu-nication in Early Embryonic Development. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 6, 94, doi:10.3389/fcell.2018.00094.

- Stahl, P.D.; Raposo, G. Extracellular Vesicles: Exosomes and Microvesicles, Integrators of Homeostasis. Physiology 2019, 34, 169–177, doi:10.1152/physiol.00045.2018.

- Alderton, G.K. Metastasis. Exosomes drive premetastatic niche formation. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2012, 12, 447, doi:10.1038/nrc3304.

- Di Vizio, D.; Morello, M.; Dudley, A.C.; Schow, P.W.; Adam, R.M.; Morley, S.; Mulholland, D.; Rotinen, M.; Hager, M.H.; Insabato, L.; et al. Large oncosomes in human prostate cancer tissues and in the circulation of mice with metastatic disease. Am. J. Pathol. 2012, 181, 1573–1584, doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.07.030.

- Peinado, H.; Alečković, M.; Lavotshkin, S.; Matei, I.; Costa-Silva, B.; Moreno-Bueno, G.; Hergueta-Redondo, M.; Williams, C.; García-Santos, G.; Ghajar, C.; et al. Melanoma exosomes educate bone marrow progenitor cells toward a pro-metastatic phenotype through MET. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 883–891, doi:10.1038/nm.2753.

- Bagnato, G.; Harari, S. Cellular interactions in the pathogenesis of interstitial lung diseases. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2015, 24, 102–114.

- Bartel, S.; Deshane, J.; Wilkinson, T.; Gabrielsson, S. Extracellular Vesicles as Mediators of Cellular Cross Talk in the Lung Microenvironment. Front. Med. 2020, 7, 326–326, doi:10.3389/fmed.2020.00326.

- Lee, H.; Abston, E.; Zhang, D.; Rai, A.; Jin, Y. Extracellular Vesicle: An Emerging Mediator of Intercellular Crosstalk in Lung Inflammation and Injury. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.00924.

- Soni, S.; Wilson, M.R.; O’Dea, K.P.; Yoshida, M.; Katbeh, U.; Woods, S.J.; Takata, M. Alveolar macrophage-derived mi-crovesicles mediate acute lung injury. Thorax 2016, 71, 1020–1029, doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-208032.

- Ye, C.; Li, H.; Bao, M.; Zhuo, R.; Jiang, G.; Wang, W. Alveolar macrophage—Derived exosomes modulate severity and out-come of acute lung injury. Aging 2020, 12, 6120–6128, doi:10.18632/aging.103010.

- Admyre, C.; Grunewald, J.; Thyberg, J.; Gripenbäck, S.; Tornling, G.; Eklund, A.; Scheynius, A.; Gabrielsson, S. Exosomes with major histocompatibility complex class II and co-stimulatory molecules are present in human BAL fluid. Eur. Respir. J. 2003, 22, 578–583.

- Nana-Sinkam, S.P.; Acunzo, M.; Croce, C.M.; Wang, K. Extracellular Vesicle Biology in the Pathogenesis of Lung Disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 196, 1510–1518, doi:10.1164/rccm.201612-2457PP.

- Holtzman, J.; Lee, H. Emerging role of extracellular vesicles in the respiratory system. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 887–895, doi:10.1038/s12276-020-0450-9.

- Skeoch, S.; Weatherley, N.; Swift, A.J.; Oldroyd, A.; Johns, C.; Hayton, C.; Giollo, A.; Wild, J.M.; Waterton, J.C.; Buch, M.; et al. Drug-Induced Interstitial Lung Disease: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 356, doi:10.3390/jcm7100356.

- Novelli, F.; Neri, T.; Tavanti, L.; Armani, C.; Noce, C.; Falaschi, F.; Bartoli, M.L.; Martino, F.; Palla, A.; Celi, A.; et al. Pro-coagulant, tissue factor-bearing microparticles in bronchoalveolar lavage of interstitial lung disease patients: An observation-al study. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e95013, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095013.

- Qazi, K.R.; Torregrosa Paredes, P.; Dahlberg, B.; Grunewald, J.; Eklund, A.; Gabrielsson, S. Proinflammatory exosomes in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with sarcoidosis. Thorax 2010, 65, 1016–1024.

- Martinez-Bravo, M.J.; Wahlund, C.J.; Qazi, K.R.; Moulder, R.; Lukic, A.; Rådmark, O.; Lahesmaa, R.; Grunewald, J.; Eklund, A.; Gabrielsson, S. Pulmonary sarcoidosis is associated with exosomal vitamin D-binding protein and inflammatory mole-cules. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2017, 139, 1186–1194, doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2016.05.051.

- Wahlund, C.J.E.; Gucluler Akpinar, G.; Steiner, L.; Ibrahim, A.; Bandeira, E.; Lepzien, R.; Lukic, A.; Smed-Sörensen, A.; Kullberg, S.; Eklund, A.; et al. Sarcoidosis exosomes stimulate monocytes to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines and CCL2. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 15328, doi:10.1038/s41598-020-72067-7.

- Adams, T.S.; Schupp, J.C.; Poli, S.; Ayaub, E.A.; Neumark, N.; Ahangari, F.; Chu, S.G.; Raby, B.A.; DeIuliis, G.; Januszyk, M.; et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals ectopic and aberrant lung-resident cell populations in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaba1983, doi:10.1126/sciadv.aba1983.

- Reyfman, P.A.; Walter, J.M.; Joshi, N.; Anekalla, K.R.; McQuattie-Pimentel, A.C.; Chiu, S.; Fernandez, R.; Akbarpour, M.; Chen, C.I.; Ren, Z.; et al. Single-Cell Transcriptomic Analysis of Human Lung Provides Insights into the Pathobiology of Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 199, 1517–1536, doi:10.1164/rccm.201712-2410OC.

- Kang, J.H.; Jung, M.Y.; Choudhury, M.; Leof, E.B. Transforming growth factor beta induces fibroblasts to express and release the immunomodulatory protein PD-L1 into extracellular vesicles. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 2213–2226, doi:10.1096/fj.201902354R.

- Guiot, J.; Cambier, M.; Boeckx, A.; Henket, M.; Nivelles, O.; Gester, F.; Louis, E.; Malaise, M.; Dequiedt, F.; Louis, R.; et al. Macrophage-derived exosomes attenuate fibrosis in airway epithelial cells through delivery of antifibrotic miR-142-3p. Thorax 2020, 75, 870–881.

- Lacy, S.H.; Woeller, C.F.; Thatcher, T.H.; Pollock, S.J.; Small, E.M.; Sime, P.J.; Phipps, R.P. Activated Human Lung Fibroblasts Produce Extracellular Vesicles with Antifibrotic Prostaglandins. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2019, 60, 269–278, doi:10.1165/rcmb.2017-0248OC.

- Martin-Medina, A.; Lehmann, M.; Burgy, O.; Hermann, S.; Baarsma, H.A.; Wagner, D.E.; De Santis, M.M.; Ciolek, F.; Hofer, T.P.; Frankenberger, M.; et al. Increased Extracellular Vesicles Mediate WNT5A Signaling in Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 198, 1527–1538, doi:10.1164/rccm.201708-1580OC.

- Gradl, D.; Kühl, M.; Wedlich, D. The Wnt/Wg signal transducer beta-catenin controls fibronectin expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999, 19, 5576–5587, doi:10.1128/mcb.19.8.5576.

- Barnes, P.J.; Baker, J.; Donnelly, L.E. Cellular Senescence as a Mechanism and Target in Chronic Lung Diseases. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 200, 556–564, doi:10.1164/rccm.201810-1975TR.

- Schafer, M.J.; White, T.A.; Iijima, K.; Haak, A.J.; Ligresti, G.; Atkinson, E.J.; Oberg, A.L.; Birch, J.; Salmonowicz, H.; Zhu, Y.; et al. Cellular senescence mediates fibrotic pulmonary disease. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 14532, doi:10.1038/ncomms14532.

- Kadota, T.; Fujita, Y.; Yoshioka, Y.; Araya, J.; Kuwano, K.; Ochiya, T. Emerging role of extracellular vesicles as a senes-cence-associated secretory phenotype: Insights into the pathophysiology of lung diseases. Mol. Asp. Med. 2018, 60, 92–103, doi:10.1016/j.mam.2017.11.005.

- Kadota, T.; Yoshioka, Y.; Fujita, Y.; Araya, J.; Minagawa, S.; Hara, H.; Miyamoto, A.; Suzuki, S.; Fujimori, S.; Kohno, T.; et al. Extracellular Vesicles from Fibroblasts Induce Epithelial Cell Senescence in Pulmonary Fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2020, doi:10.1165/rcmb.2020-0002OC.