Literature about sustainability and sustainable businesses has become a large field of study during the last years. This field is growing so fast that there are sub-areas or bodies of literature within the sustainability which scopes with clear boundaries between each other. This has caused the apparition of several methodologies and tools for turning traditional companies into sustainable business models. This paper aims to develop the descriptive stage of the theory building process through a careful review of literature to create the first phase of a theory about corporate sustainability. It provides the following classification of concepts retrieved from the observation of the state of art: holistic sustainability, sustainable business models, sustainable methodologies, sustainable operations, and sustainability-oriented innovation. In addition, it seeks to establish relationships between the sustainable concepts and the expected outcomes that their implementation can generate among companies and organizations. Finally, it gives an overview of possibilities for managers that want to embed sustainability in their firms and clear paths of research for keeping the building of the theory about corporate sustainability as a process of constant iteration and improvement.

- sustainability

- holistic sustainability

- sustainab

1. Introduction

The impact of sustainability in our society is so profound that some authors call this phenomenon the sustainability revolution [1]. From a managerial point of view, sustainability comprises the amount of sustainable practices implemented by companies as a response to new challenges and stakeholder pressures. These practices can be applied in several areas of the company, from corporate strategy to business processes[2]. In fact, there is a debate between researchers who state that sustainable practices are only able to reduce costs or improve the company’s environmental, social, and governance (ESG) ratings but are not able to build competitive advantage. On the other hand, there are those who defend companies that can integrate sustainability into their strategy and lead them to a better performance and a competitive advantage generation [3].

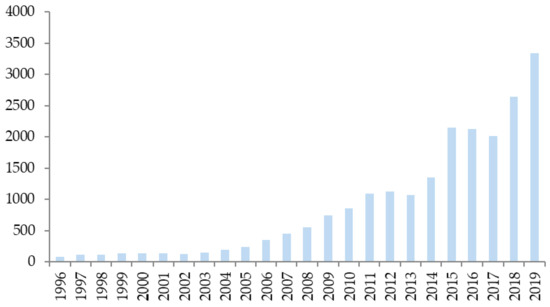

From an academic point of view, research about the field of corporate sustainability has been increasing gradually since 1996 reaching the peak of 3338 publications in 2019. Figure 1 contains a visual diagram that shows the number of publications about sustainability retrieved from the academic database Web of Science.

Therefore, this work tries to establish the relationship between the sustainable practices adopted by organizations and the results achieved. The analysis of this relationship has been performed under the frame of the theory building process [4][5]. Specifically, it aims to analyze the literature about corporate sustainability in order to know the way that managers embrace environmental practices across their processes, business models, innovation orientation, and strategic planning.

There are several areas of study in the field of management that try to help managers make better decisions for their businesses. The field of corporate sustainability or sustainability management shows a similar pattern to the field of management. This area of study was originated by Taylor with his seminal work Principles of Scientific Management in 1911 [5], published after the Industrial Revolution. After that, other important works about management were published during the mid-20th century (as e.g., Schumpeter in 1942[6] or Weber in 1947 [7]). Currently, management is a field of study with a wide range of publications, scientific works, books, and educational programs.

For instance, Porter [8] states that there are two different fields that managers need to take into account when they are going to make decisions: strategic decisions and operational effectiveness decisions. Kaplan and Norton [9] deployed the Balanced Scorecard with the aim of helping executives to align their business’s purpose with the strategy and operations of the organization. Even the field of strategy holds different sub-areas like “corporate strategies”, “competitive strategies”, or “growth strategies”[10].

On the other hand, there are even authors that have developed some proto-theories about sustainability[11][12]; those works have not reached the acceptance like the theories or frameworks published in the traditional management field. Nevertheless, as this topic is getting more complex, it is giving birth to more sub-fields or sub-areas of study and leading to a new way to do business. The establishment of robust frameworks and theories is needed.

2. The Theory Building Process

The theory building process lies in the identification of the causal mechanisms that lead to specific results. The theory building process deployed for this paper is based on the formal definition of theory[13][14][15] using the empirical research process[16].

There are two sides to every lap around the theory-building process: an inductive side (descriptive stage) and a deductive side (normative stage).

Within the descriptive stage researchers have to go through the following steps:

-

Observation: During this process, researchers observe phenomena, and describe and measure all the details they perceive. The data extracted from the phenomena analysis often generate abstractions that can be termed “constructs”.

-

Categorization: This categorization attempts to simplify and organize the information in order to detect relationships between the phenomena and expected outcomes. During this process, researchers can refer to these schemes as either “concepts” or “conceptual frameworks”.

-

Associations: During this step, researchers analyze the correlation between attributes and the outcomes observed. This gives birth to statements of associations, which can be also called “models”[17] (p. 30).

3. Results

This section shows the results obtained in the development of each stage of the building process of the theory of corporate sustainability (observation, classification, and definition of relationships) and what the relationships are between them.

3.1. Observation

In this case, the phase of observation was carried out through a meticulous process of literature review of academic papers, publications from private companies, and reports.

Sustainability has evolved dramatically over the last years. Decades ago, public administrations and governments started to develop environmental legislation that needed to be accomplished by corporations, especially large corporations like companies from oil industry or big pollutants. Then, international organizations created voluntary certificates like ISO 14001 (International Standard Organization) or EMAS (Eco-Management and Audit Scheme). In addition, those corporations that wanted to go one step beyond had the chance to design eco-innovative practices among their business processes. These kinds of practices allowed companies to make products decreasing the environmental impact or launching new products whose consumption does not harm our planet.

Currently, new business models that place sustainability in their core and purpose are emerging. Hence, those companies try to offer value to customers enhancing a sustainable society.

During the observation phase, it was remarkable to notice that there are numerous ways to tackle sustainability from a business point-of-view and, apparently, all of them lead to better results for companies, such as more turnover, higher number of customers, better customer engagement, or more operational efficiency.

3.2. Classification

The analysis of the state of the art showed that there are different types of bodies of literature about sustainability. These fields of research are framed under the area of sustainability because they pursue the improvement of environmental practices through all the areas of the company’s value chain.

However, setting boundaries between each body of literature is determined by the researchers’ different perspectives on their works to tackle climate change. For instance, the environmental policies and practices suggested by researchers can affect only a specific area of the company or they can be transversal throughout the organization. Some groups of policies can be just focused on reshaping processes whilst others have a holistic approach and transform the relationship between the company and its stakeholders.

There have been some attempts to draw the boundary between different concepts or bodies of knowledge from academic literature, the aim of which is to classify the sustainable practices that companies can implement in their organizations to become more sustainable[18][19].

Consequently, those groups of bodies of literature, according to the literature of theory building process, may generate concepts that will lead to further relationships between each other.

In order to offer an accurate classification of the different ways companies can become sustainable, it is necessary to determine the appropriate level of abstraction of each of the concepts, which will allow researchers to classify each type of sustainable action in its concept.

3.2.1. Concepts

According to Jabareen [20], concepts need to be deconstructed to identify their main attributes, characteristics, assumptions, and role. The bodies of literature detected in the classification phase have clear boundaries with their own attributes and characteristics, so they can be considered ”concepts”. The following table (Table 1) shows the name of the concepts, a description of each concept, a concept categorization according to its ontological, epistemological, or methodological role, and the most important references for each concept.

Table 1. Name, description and concept categorization from each sustainability related concept.

| Concept | Description | Concept Categorization | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Holistic sustainability | Policies with a long-term vision with a broad perspective that encompass sustainable actions to reshape the interaction of the company with its stakeholders. | Ontological concept | Porter and Kramer, 2011; Nidumolu et al., 2009; Ioannou and Serafeim, 2019 |

| Sustainable business models | Business model that creates competitive advantage through superior customer value and contributes to sustainable development of the company and society. | Epistemological concept | Lüdeke-Freund, 2010; Schaltegger et al., 2016; Bocken et al., 2014 |

| Sustainable methodologies | Methodologies and tools designed for managers to improve the company’s performance and sustainability. | Methodological concept | Joyce and Paquin, 2016; França et al., 2016; Bocken et al. 2013; Rodríguez-Vilá and Bharadwaj, 2017 |

| Sustainable operations | Activities and business processes that reduce the environmental impact only focusing on specific areas of the organization (i.e., product development, waste management, eco-innovation, etc.). | Methodological concept | Segarra-Oña, 2012; Cheng et al., 2014 |

| Sustainability-oriented innovation | Research field that combines two or more concepts to improve sustainability among corporations. | Methodological concept | Hansen and Große-Dunker, 2013; Geradts and Bocken, 2019 |

The creation of these concepts sets boundaries which are essential to decide which areas the company will innovate in and what the scope will be [16]. For instance, sustainable practices classified in the concept of sustainable operations, such as life cycle assessment (LCA), need a clear scope that determines the areas of the company that will be studied in order to calculate the environmental impact[21].

However, it is harder to identify if some activities are only circumscribed to the concept of sustainable operations or they surpass the boundaries to the concept of sustainable business models. This issue was studied back in 1971 by Habermas and Luhmann[22], who defended human beings’ work to reduce complexity through the implementation of system boundaries. In fact, the design of those boundaries and concept creation are essential stages of the theory building process presented previously.

5. Discussion

The capability of linking those sustainable concepts with the concepts of strategy and operational effectiveness developed by Porter (1985)[23] is remarkable. Thus, practices embedded in holistic sustainability, sustainable business models, and the literature about sustainable-oriented innovation should be classified as strategic issues, because of their attempt to achieve a perdurable competitive advantage in differentiating the company from its competitors. According to Porter, organizations that hold competitive advantage are able to perform different activities from competitors or develop similar activities as those of rivals in different ways[23].

In addition, sustainable methodologies and sustainable operations are concepts that will fit in the concept of operational effectiveness because these kinds of actions allow companies to deploy a myriad of business processes (production, marketing, delivering, and so on) in a faster way or using fewer resources than rivals.

From a managerial point of view, sustainability should not be siloed or regarded as a department with clear boundaries and tasks. The effect of eco-innovative processes or environmental certificates may report results in the short-term. However, in order to tackle the basis of competition, it is necessary to integrate sustainability within the business model because consumers consider sustainability another performance attribute of the product or service [24][25].

The state of the art on sustainability shown above has generated a deep understanding of how environmental practices transform companies. There are clear hints in the literature that establish causal mechanisms between the implementation of sustainable practices among companies and its performance improvement [3].

However, the results expected by managers will be different depending on the sustainable practice implemented. For instance, corporate social responsibility initiatives increase operational effectiveness within the company and economic context. Consequently, managing sustainability this way ignores the depth of the corporate sustainable field and it does not place sustainability at an appropriate level in a strategic decision[26].

Making decisions about sustainability as a silo without taking into account the strategic decisions made by board members is an example of the separation fallacy [27][28][29]. Separation fallacy is the belief that business decisions should be made independently from broader ethical concerns, such as the environment and social issues. This is the reason management areas like finance and accountability are treated independently from sustainability. In fact, as Ioannis and Hawn state[30], it has not been possible to successfully integrate environmental issues into strategy.

One example of the importance of positioning sustainability as a strategic element for managers comes from the research done by Ioannis and Serafeim[1], who state that companies that implement unique sustainable practices are more likely to differentiate themselves from their competitors and report more benefits. However, those companies that adopt ‘common’: practices are more likely to be associated to companies that try to survive instead of outperforming. Another conclusion that emerged is that organizations that led the adoption of sustainable practices in its market niche and were able to remain leaders through the adoption of unique sustainable practices achieve higher levels of performance, since these companies have built barriers to imitation and gained a good position in their client base hard to copy by competitors.

Research about the theory building process in social sciences holds that the third step consists of defining relationships, so, the concepts presented above may have relationships and even synergies among companies when implemented in a combined way.

Additionally, sustainable practices included in various concepts cannot be implemented separately if managers are looking to achieve both a sustainable and a profitable company[1]. Hence, to turn a traditional company into a sustainable one, it is necessary to embed sustainability through a holistic point of view which should enhance executives to boost a cultural shift among employees. It is then necessary to reshape its business models in a deep way to deliver superior value to customers improving the environmental and social impact. In order to transform a traditional business model into a sustainable business model, it is necessary to use sustainable methodologies and redefine processes which could be accompanied by sustainable-oriented innovation policies. Therefore, the element that will help the new company perform and achieve better results will be a sustainable design of the operations carried out in the company.

Consequently, the actions included in each of the concepts presented above will lead the company to obtain different types of results (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Diagram that shows a brief description of the results that managers can expect after the implementation of activities fitted in each sustainable concept. Own elaboration.

Only the combination of activities provided from different sustainable concepts will lead organizations to turn their traditional business into a sustainable company, capable of surpassing their competitors, targeting new customers, penetrating new markets and launching new products and services. Turning a traditional business into a sustainable one is a hard job and a challenge for managers and consultants. Although sustainable methodologies are helpful tools in overcoming that challenge, people responsible for leading this change need to have a framework that allows them to shift the strategy of the business, the business model of the company, and the whole range of processes carried out across the organization.

Integrating sustainability through those concepts into the strategy and operations of a company is a long-term proposition. An adequate sustainable strategy will align the activities and operations of the organization sharing a sustainable culture that will lead to an improvement in economic performance. The longer the firm chases value creation through sustainability, the more it will learn about meeting customer and social needs in a profitable way and the better it will integrate new sustainable operations, methodologies, and even business models into every area of the company[31].

6. Conclusions

This research aims to contribute to the development of sustainability through the classification of different bodies of literature and the development of a theory of corporate sustainability. Firstly, a careful and deep review about sustainability was carried out, which led to the classification of the concepts of “holistic sustainability”, “sustainable business models”, “sustainable methodologies”, and” sustainable operations”.

Secondly, the phase of relationship definition has been analyzed through the review of the literature on the line of the research called “sustainability-oriented innovation”, since these works focused on the study of the results generated in companies that implement activities encompassed in different concepts.

Finally, there is a need to enhance sustainability as a strategic topic for those companies that are heading towards becoming sustainable. Currently, companies that want to reshape their business model need to modify numerous aspects: from the company’s culture to the most basic business process and they will need support from the board member to the operators. Therefore, only the proper combination of concepts will lead companies to better performance and more satisfying results.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su13010273

References

- Edwards, A.R. The Sustainability Revolution: Portrait of a Paradigm Shift; New Society Publishers: Gabriola Island, BC, Canada, 2005.

- Winston, A. What 1,000 CEOs Really Think About Climate Change and Inequality. Harv. Bus. Rev.: Brighton, MA, USA, 2019. Available online: https://hbr.org/2019/09/what-1000-ceos-really-think-about-climate-change-and-inequality (accessed on 9 October 2020)

- Ioannis, I.; Serafeim, G. Corporate Sustainability: A Strategy? HBS Working Paper: Boston, MA, USA, 2019; No. 19-065. Available online: https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Publication%20Files/19-065_16deb9d6-4461-4d2f-8bbe-2c74b5beffb8.pdf (accesed on 10 January 2020)

- Christensen, C.M.; Carlile, P.D. Course Research: Using the Case Method to Build and Teach Management Theory. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 2009, 8, 240–251.

- Taylor, F. The Principles of Scientific Management; Harper & Brothers: New York, USA, 1911.

- Schumpeter, J. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy. Edition 2003; George Allen & Unwin: New York, NY, USA, 1947.

- Weber, M., Parsons, T. and Henderson, A. The Theory of Social and Economic Organization, 1st ed; New York University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1947.

- Porter, M. What is Strategy? Harvard Business Review: Brighton, MA, USA, 1996; 74, no. 6 November–December, 61–78.

- Kaplan, R.; Norton, D. The Balanced Scorecard–Measures that Drive Performance; Harvard Business Review: Brighton, MA, USA, 1992.

- Sainz de Vicuña, J.M. El Plan Estratégico en la Práctica, 5th ed.; ESIC: Madrid, Spain, 2017.

- Starik, M.; Kanashiro, P. Toward a Theory of Sustainability Management: Uncovering and Integrating the Nearly Obvious Organ. Environ. 2013, 26, 17–30.

- Chang, R.; Jian, Z.; Zhen-Yu, Z.; George, Z.; Xiaolong, G.; Veronica, S. Evolving theories of sustainability and firms: History, future directions and implications for renewable energy research. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 72, 48–56.

- Hunt, S.D. Modern Marketing Theory: Critical Issues in the Philosophy of Marketing Science; Southwestern Publishing: Cincinnati, OH, USA, 1991.

- Bunge, M. Scientific Research 1: The Search for System; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1967.

- Reynolds, P.D. A Primer in Theory Construction; Bobbs-Merrill Educational Publishing: Indianapolis, IN, USA, 1971.

- Wacker, J.G. A Definition of Theory: Research Guidelines for Different Theory-Building Research Methods in Operations Management. J. Oper. Manag. 1998, 16, 361–385.

- Turban, E.; Meredith, J.R. Fundamentals of Management Science, 5th ed.; Irwin: Homewood, IL, USA, 1991.

- Rodrigues, M.; Franco, M. The Corporate Sustainability Strategy in Organisations: A Systematic Review and Future Directions. Sustainability. 2019, 11, 6214.

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Geradts, T.H.J. Barriers and drivers to sustainable business model innovation: Organization design and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Plan. 2019, 101950, doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2019.101950 [Open Access].

- Jabareen, Y. Building a Conceptual Framework: Philosophy, Definitions, and Procedure. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2009, 8, 49–62.

- ISO Life Cycle Perspective-what ISO14001 Includes. 2016. Available online: https://committee.iso.org/files/live/sites/tc207sc1/files/Lifecycle%20perspective%20%20March%202016.pdf (accessed on 9 September 2017).

- Habermas, J.; Luhmann, N. Theorie der Gesellschaft oder Sozialtechnologie; Suhrkamp: Frankfurt, Germany, 1971.

- Porter, M.E. The Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1985; (Republished with a new introduction, 1998).

- Winston. Green to Gold: How Smart Companies Use Environmental Strategy to Innovate, Create Value, and Build Competitive Advantage; Yale University Press: 2006. Print.

- Porter, M.; van der Linde, C. Green and Competitive: Ending the Stalemate; HBR 1995; Volume 73, pp. 120–133.Lüdeke-Freund, F.; Schaltegger, S.; Dembek, K. Strategies and drivers of sustainable business model innovation. In Handbook of Sustainable Innovation; Edward Elgar: Broadheath, UK, 2019; Chapter: 6.

- Freeman, R.E. The politics of stakeholder theory: Some future directions. Bus. Ethics Q. 1994, 4, 409–421.

- Harris, J.D.; Freeman, R.E. The impossibility of the separation thesis: A response to Joakim Sandberg. Bus. Ethics Q. 2008, 18, 541–548, doi:10.2307/27673252.

- Sen, A. On Ethics and Economics; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1987.

- Porter, M.; Serafeim, G.; Kramer, M. Where ESG Fails. Institutional Investor. 2019. Available online: https://www.institutionalinvestor.com/article/b1hm5ghqtxj9s7/Where-ESG-Fails (accessed on 16 October 2019)

- Ioannis, I.; Hawn, O. Redefining the Strategy Field in the Age of Sustainability. In The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility: Psychological and Organizational Perspectives; SSRN. 2019. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2429870 (accessed on 15 July 2020)

- Peloza, J. Building Your Case Research Findings on the Business Case for Sustainability. Conference of Network for Business Sustainability. USA. 2009. Available online: https://slideplayer.com/slide/692604/.

- Ioannis, I.; Hawn, O. Redefining the Strategy Field in the Age of Sustainability. In The Oxford Handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility: Psychological and Organizational Perspectives; SSRN. 2019. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2429870 (accessed on 15 July 2020)

- Peloza, J. Building Your Case Research Findings on the Business Case for Sustainability. Conference of Network for Business Sustainability. USA. 2009. Available online: https://slideplayer.com/slide/692604/.