GABAA receptors (GABAARs) are ligand-gated heteropentameric ion channels, most commonly formed by 2α, 2β, and 1γ subunit. They are expressed in spinal cord dorsal horn, both at the pre- and postsynaptic site, controlling the transmission of pain, itch, touch and proprioception.

- presynaptic inhibition

- GABA

- pain

- spinal cord

- neural circuits

- synaptic transmission

1. GABAergic Inhibition on Primary Afferent Fibers

GABAergic interneurons play a critical role in regulating nociceptive signal strength and separating nociception from touch. Intrathecal application of bicuculline and strychnine (antagonists of GABAA and glycine receptors, respectively) increases responses evoked by exposure to noxious stimuli [1]. According to the gate theory of pain, proposed by Melzack and Wall [2], stimulation of tactile Aβ fibers activate inhibitory interneurons in the dorsal horn, “closing the gate” to nociceptive transmission. Conditions of disinhibition (either pharmacological or induced by persistent pain) “open the gate”, increasing pain response and causing allodynia (i.e., the perception of an innocuous stimulus as noxious).

Presynaptic GABA receptors located on PAF terminals are involved in gating both tactile and noxious stimuli in the dorsal horn. Indeed, GABA receptors of the A and B type are expressed on both nociceptive and non-nociceptive PAFs, where axo-axonic synapses have been described.

GABAA receptors (GABAARs) are ligand-gated heteropentameric ion channels, most commonly formed by 2α, 2β, and 1γ subunit. The composition of GABAARs on PAFs is heterogeneous: nociceptive C fibers express the α2, α3, and α5 subunits, while α1, α2, α3, and α5 are present on myelinated A fiber terminals [3][4][5]. The subunit β3 has been shown as the dominant β subunit expressed in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons of both A and C type: In a mouse line where the β3 subunit is selectively knocked out in primary nociceptors, the GABA current in DRG neurons is decreased and the animals exhibit hypersensitivity to noxious heat and mechanical stimulation [6].

1.1. Primary Afferent Depolarization

Presynaptic GABAARs expressed on PAF terminals mediate primary afferent depolarization (PAD) in spinal cord dorsal horn. This phenomenon, firstly described in muscle afferents [7], consists of a slow dorsal root depolarization, evoked by the stimulation of an adjacent root. Stimulation of PAFs evokes glutamate release that activates GABAergic interneurons. These neurons, in turn, release GABA binding to GABAARs expressed on PAF terminals.

The cellular mechanisms of PAD have been extensively investigated. Primary sensory neurons exhibit a higher intracellular concentration of chloride than most central neurons. This is caused by the high expression of the transporter NKCC1 (transporting Cl−, Na+ and K+ into the cell) and the low, or even undetectable, expression of KCC2 (expelling Cl− and K+ out of the cell) [8][9][10][11][12]. Due to the high Cl− intracellular concentration, the chloride equilibrium potential (ECl) in DRG neurons is about −30 mV[9][13]. Thus, the activation of GABAARs on PAF terminals produces an outward anion flux, leading to membrane depolarization and generation of PAD.

In physiological conditions, PAD exerts an inhibitory effect on glutamate release, through several possible mechanisms. PAF depolarization can lead to the inactivation of voltage-dependent Na+ and Ca+ channels, impairing the propagation of action potentials along PAFs and decreasing the calcium influx into the terminals[14][15][16][17][18]. The opening of GABAA channels could also exert a shunting effect on action potential propagation by decreasing membrane resistivity, as shown by experimental evidence and mathematical simulations [19][20][21][22]. Suprathreshold PAF depolarizations can sometimes trigger action potentials that are conducted antidromically, generating dorsal root reflexes [23][24].

Earlier studies have demonstrated the involvement of GABAARs in the generation of PAD: The GABAA antagonist picrotoxin blocks presynaptic inhibition on spinal monosynaptic reflexes, while iontophoretic application of GABA generates depolarization of group I afferent fibers [25][26]. More recently, Witschi et al. have shown that mice lacking the GABAA α2 subunit specifically in primary nociceptors exhibit a lack of effect of the GABAA modulator diazepam in potentiating PAD and decreasing inflammatory hyperalgesia, confirming the involvement of presynaptic GABAARs in PAD generation and pain inhibition [27]. Interestingly, neither glycine receptors nor gephyrin clusters have been detected on C fibers expressing GABAARs, in contrast with inhibitory synapses on postsynaptic neurons [4]. The presence of unclustered GABAARs on presynaptic terminals suggests a more diffuse mode of inhibition at these synapses, consistent with the slow kinetics of GABA-mediated PAD. Beside GABAARs, also glutamatergic receptors of the AMPA and NMDA type, expressed on PAF central terminals, have been reported to contribute to the generation of PAD in the spinal cord [28].

PAD has been proposed as one of the most powerful mechanisms of sensory control, producing several effects: (1) reduction in the effectiveness of one sensory input over the others and selective control of convergent inputs; (2) generation of surround inhibition, producing localized reactions to sensory stimuli (a small stimulus to the skin produces PAD in the same spinal cord segment, but also in many rostral and caudal segments, both ipsi- and contra-lateral); and (3) increase of the temporal contrast of a somatic sensory input. Accordingly, PAD mediated by GABAARs is composed of a phasic and a tonic component (likely mediated by receptors expressing the α5 subunit [29]): The first increases the perception of a sudden stimulus, while the latter represents the ongoing inhibition of slow changes of sensory inputs.

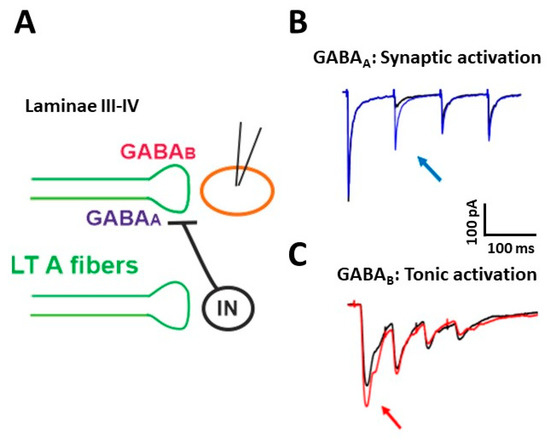

The functional properties of PAD in muscle afferents and LT cutaneous PAFs have been investigated by several studies [16][23][30][31]. We recently demonstrated that presynaptic GABAARs are involved in short term synaptic depression during repetitive stimulation of Aβ fibers [32] (Figure 1). We performed electrophysiological experiments on rat spinal cord slices, recording from unidentified laminae III–IV neurons, in voltage-clamp at −70 mV. The dorsal root attached to the slice was electrically stimulated with four pulses at the frequency of 10–20 Hz and intensity of 10–25 μA, recruiting LT A fibers, mainly of the Aβ type. The evoked excitatory postsynaptic currents (EPSCs) showed a strong depression after the first response, which was particularly evident in the second EPSC (Figure 1B, black trace). Application of the GABAA antagonist gabazine unmasked an additional component in the second EPSC (blue trace): This indicates that GABA, released after the first pulse, acts on presynaptic GABAARs, reducing glutamate release from Aβ fibers at the second stimulus. By mainly affecting the second response in a train of stimuli, presynaptic GABAARs inhibit glutamate release from PAFs with a high temporal precision, controlling the earliest part of an afferent response to touch

Figure 1. Presynaptic modulation mediated by GABAA and GABAB receptors on low threshold (LT) A fibers in deep dorsal horn (laminae III–IV). (A) Schematic representation of the circuit activating presynaptic GABA receptors. GABAA receptors can be recruited by a synaptic mechanism: an inhibitory interneuron (IN) is activated by LT A fibers and releases GABA onto fibers of the same type, causing the inhibition of glutamate release and synaptic depression. GABABRs (GABAB receptors) can tonically inhibit the release of glutamate from LT fibers. (B) Representative traces of EPSCs recorded from a lamina III–IV neuron, evoked by stimulating LT fibers with four pulses at 10 Hz. A strong depression of the second response was evident in control (black trace). Application of the GABAAR antagonist gabazine (10 μM) increased the second EPSC (blue trace, arrow) in 10 out of 17 recorded neurons. (C) Representative traces of EPSCs, evoked by stimulating LT A fibers with four pulses at 20 Hz. In the presence of the GABAB antagonist CGP 55,845 (5 μM), the first EPSC increased in five out of 13 lamina III–IV neurons (red trace, arrow). Modified with permission from [33].

Using a cesium-fluoride intracellular solution, able to block GABAARs expressed on the recorded neuron, the effect of gabazine on the second EPSC was not abolished, confirming the involvement of presynaptic GABAARs. Application of strychnine was ineffective in increasing the second EPSC, indicating that glycine receptors are not importantly involved in presynaptic modulation on PAF terminals. By recording at −10 mV from laminae III–IV neurons and stimulating at Aβ fiber threshold, we observed inhibitory postsynaptic currents, mediated by both GABAA and glycine receptors. Thus, GABAARs modulate the first synapse between Aβ fibers and dorsal horn neurons in two ways: through a negative feedback mechanism at PAF terminals and by a feed-forward control on postsynaptic neurons.

Differently from LT afferent fibers, functional studies about PAD on HT nociceptive fibers are still limited. By using an ex vivo spinal cord preparation, Fernandes et al. [34] recently reported that noxious C-fiber input to rat lamina I neurons (both projection and local neurons) is presynaptically modulated by Aβ, Aδ, and C fibers. Thus, presynaptic inhibition mediated by these different groups of afferents may control the inflow of nociceptive input to superficial dorsal horn, playing a role in nociceptive discrimination and lateral inhibition.

1.2. GABAB Receptors as Presynaptic Modulators

In addition to GABAA, activation of GABAB receptors (GABABRs), expressed on nociceptive and non-nociceptive PAF terminals, also contributes to presynaptic inhibition, exerting analgesic and anti-hyperalgesic effects [35]. GABABRs are G protein-coupled receptors, expressed as obligate heterodimers of the two subunits GABAB1 and GABAB2. The GABAB1 isoforms 1a and 1b, together with the subunit GABAB2, have been found in small and large DRG neurons and in the spinal cord, both at PAF terminals and on dorsal horn neurons [36][37][33]. Endogenous or exogenous activation of GABABRs in superficial dorsal horn causes both pre- and postsynaptic effects. Electrophysiological studies performed on rats have shown that presynaptic GABABRs inhibit pinch- and touch-evoked synaptic responses in vivo [38] and decrease glutamate and peptide release from A- and C-type PAFs and dorsal horn neurons [37][39][40][41][42]. The inhibitory effect of GABABRs on transmitter release is due to the concurrent inhibition of presynaptic calcium channels [43][44] and release machinery downstream of calcium entry into the nerve terminals [45].

By performing electrophysiological experiments similar to those described above, we showed that the block of GABABRs increases the first EPSC in a train of four stimuli, recorded from lamina III–IV neurons [33] (Figure 1C, red trace). This suggests that, differently from GABAARs, which require the release of GABA through synaptic activation, GABABRs are tonically activated, confirming the finding of a previous study performed in lamina II [46].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijms22010414

References

- Roberts, A.; Komisaruk, R. Nociceptive responses to altered GABAergic activity at the spinal cord. Life Sci. 1986, 39, 1667–1674.

- Melzack, R.; Wall, P.D. Pain mechanisms: A new theory. Science 1965,150, 971–979.

- Paul, J.; Zeilhofer, H.U.; Fritschy, J.M. Selective Distribution of GABAA Receptor Subtypes in Mouse Spinal Dorsal Horn Neurons and Primary Afferents. J. Comp. Neurol. 2012, 520, 3895–3911.

- Lorenzo, L.E.; Godin, A.G.; Wang, F.; St-Louis, M.; Carbonetto, S.; Wiseman, P.W.; Ribeiro-da-Silva, A.; De Koninck, Y. Gephyrin Clusters Are Absent from Small Diameter Primary Afferent Terminals despite the Presence of GABAA Receptors. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 8300–8317.

- Ma, W.; Saunders, P.A.; Somogyi, R.; Poulter, M.O.; Barker, J.L. Ontogeny of GABAA Receptor Subunit MRNAs in Rat Spi-nal Cord and Dorsal Root Ganglia. J. Comp. Neurol. 1993, 338, 337–359.

- Chen, J.T.C.; Guo, D.; Campanelli, D.; Frattini, F.; Mayer, F.; Zhou, L.; Kuner, R.; Heppenstall, P.A.; Knipper, M.; Hu, J. Pre-synaptic GABAergic Inhibition Regulated by BDNF Contributes to Neuropathic Pain Induction. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5331.

- Frank, K.; Fuortes, M.G.F. Presynaptic and postsynaptic inhibition of monosynaptic reflexes. Fed. Proc. 1957, 16, 39–40.

- Gallagher, J.P.; Higashi, H.; Nishi, S. Characterization and Ionic Basis of GABA-Induced Depolarizations Recorded in Vitro from Cat Primary Afferent Neurones. J. Physiol. 1978, 275, 263–282.

- Alvarez-Leefmans, F.J.; Gamiño, S.M.; Giraldez, F.; Noguerón, I. Intracellular Chloride Regulation in Amphibian Dorsal Root Ganglion Neurones Studied with Ion-Selective Microelectrodes. J. Physiol. 1988, 406, 225–246.

- Sung, K.W.; Kirby, M.; McDonald, M.P.; Lovinger, D.M.; Delpire, E. Abnormal GABAA Receptor-Mediated Currents in Dor-sal Root Ganglion Neurons Isolated from Na-K-2Cl Cotransporter Null Mice. J. Neurosci.. 2000, 20, 7531–7538.

- Gilbert, D.; Franjic-Würtz, C.; Funk, K.; Gensch, T.; Frings, S.; Möhrlen, F. Differential Maturation of Chloride Homeostasis in Primary Afferent Neurons of the Somatosensory System. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2007, 25, 479–489.

- Mao, S.; Garzon-Muvdi, T.; Di Fulvio, M.; Chen, Y.; Delpire, E.; Alvarez, F.J.; Alvarez-Leefmans, F.J. Molecular and Func-tional Expression of Cation-Chloride Cotransporters in Dorsal Root Ganglion Neurons during Postnatal Maturation. J. Neu-rophysiol.. 2012, 108, 834–852.

- Rocha-González, H.I.; Mao, S.; Alvarez-Leefmans, F.J. Na+,K+,2Cl- Cotransport and Intracellular Chloride Regulation in Rat Primary Sensory Neurons: Thermodynamic and Kinetic Aspects. J. Neurophysiol.. 2008, 100, 169–184.

- Graham, B.; Redman, S. A Simulation of Action Potentials in Synaptic Boutons during Presynaptic Inhibition. J. Neurophysiol. 1994, 71, 538–549.

- Walmsley, B.; Graham, B.; Nicol, M.J. Serial E-M and Simulation Study of Presynaptic Inhibition along a Group Ia Collateral in the Spinal Cord. J. Neurophysiol. 1995, 74, 616–623.

- Rudomin, P.; Schmidt, R.F. Presynaptic Inhibition in the Vertebrate Spinal Cord Revisited. Exp. Brain Res. 1999, 129, 1–37.

- French, A.S.; Panek, I.; Torkkeli, P.H. Shunting versus Inactivation: Simulation of GABAergic Inhibition in Spider Mechano-receptors Suggests That Either Is Sufficient. Neurosci.. Res. 2006, 55, 189–196.

- Takkala, P.; Zhu, Y.; Prescott, S.A. Combined Changes in Chloride Regulation and Neuronal Excitability Enable Primary Af-ferent Depolarization to Elicit Spiking without Compromising Its Inhibitory Effects. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2016, 12, e1005215.

- Segev, I. Computer Study of Presynaptic Inhibition Controlling the Spread of Action Potentials into Axonal Terminals. J. Neurophysiol. 1990, 63, 987–998.

- Cattaert, D.; El Manira, A. Shunting versus Inactivation: Analysis of Presynaptic Inhibitory Mechanisms in Primary Afferents of the Crayfish. J. Neurosci. 1999, 19, 6079–6089.

- Cattaert, D.; Libersat, F.; El Manira, A. A Presynaptic Inhibition and Antidromic Spikes in Primary Afferents of the Crayfish: A Computational and Experimental Analysis. J. Neurosci. 2001, 21, 1007–1021.

- Verdier, D.; Lund, J.P.; Kolta, A. GABAergic Control of Action Potential Propagation along Axonal Branches of Mammalian Sensory Neurons. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 2002–2007.

- Willis, W.D. Dorsal Root Potentials and Dorsal Root Reflexes: A Double-Edged Sword. Exp. Brain. Res. 1999, 124, 395–421.

- Prescott, S.A.; Sejnowski, T.J.; De Koninck, Y. Reduction of Anion Reversal Potential Subverts the Inhibitory Control of Firing Rate in Spinal Lamina I Neurons: Towards a Biophysical Basis for Neuropathic Pain. Mol. Pain. 2006, 2, 32.

- Eccles, J.C.; Schmidt, R.; Willis, W.D. PHARMACOLOGICAL STUDIES ON PRESYNAPTIC INHIBITION. J. Physiol. 1963, 168, 500–530.

- Rudomín, P.; Engberg, I.; Jiménez, I. Mechanisms Involved in Presynaptic Depolarization of Group I and Rubrospinal Fibers in Cat Spinal Cord. J. Neurophysiol. 1981, 46, 532–548.

- Witschi, R.; Punnakkal, P.; Paul, J.; Walczak, J.S.; Cervero, F.; Fritschy, J.M.; Kuner, R.; Keist, R.; Rudolph, U.; Zeilhofer, H.U. Presynaptic alpha2-GABAA Receptors in Primary Afferent Depolarization and Spinal Pain Control. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 8134–8142.

- Bardoni, R. Role of Presynaptic Glutamate Receptors in Pain Transmission at the Spinal Cord Level. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2013, 11, 477–483.

- Lucas-Osma, A.M.; Li, Y.; Lin, S.; Black, S.; Singla, R.; Fouad, K.; Fenrich, K.K.; Bennett, D.J. Extrasynaptic alpha5-GABAA Re-ceptors on Proprioceptive Afferents Produce a Tonic Depolarization That Modulates Sodium Channel Function in the Rat Spinal Cord. J. Neurophysiol. 2018, 120, 2953–2974.

- Rudomin, P.; Jiménez, I.; Chávez, D. Differential Presynaptic Control of the Synaptic Effectiveness of Cutaneous Afferents Evidenced by Effects Produced by Acute Nerve Section. J. Physiol. 2013, 591, 2629–2645.

- Fink, A.J.P.; Croce, K.R.; Huang, Z.J.; Abbott, L.F.; Jessell, T.M.; Azim, E. Presynaptic Inhibition of Spinal Sensory Feedback Ensures Smooth Movement. Nature 2014, 508, 43–48.

- Betelli, C.; MacDermott, A.B.; Bardoni, R.; Transient, Activity Dependent Inhibition of Transmitter Release from Low Thresh-old Afferents Mediated by GABAA Receptors in Spinal Cord Lamina III/IV. Mol. Pain. 2015, 11, 1–14.

- Salio, C.; Merighi, A.; Bardoni, R. GABAB Receptors-Mediated Tonic Inhibition of Glutamate Release from Aβ Fibers in Rat Laminae III/IV of the Spinal Cord Dorsal Horn. Mol. Pain. 2017, 13, 1–16.

- Fernandes, E.C.; Pechincha, C.; Luz, L.L.; Kokai, E.; Szucs, P.; Safronov, B.V. Primary Afferent-Driven Presynaptic Inhibition of C-Fiber Inputs to Spinal Lamina I Neurons. Prog. Neurobiol. 2020, 188, 101786.

- Malcangio, M. GABAB Receptors and Pain. Neuropharmacology 2018, 136, 102–105.

- Towers, S.; Princivalle, A.; Billinton, A.; Edmunds, M.; Bettler, B.; Urban, L.; Castro-Lopes, J.; Bowery, N.G. GABAB Receptor Protein and MRNA Distribution in Rat Spinal Cord and Dorsal Root Ganglia. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2000, 12, 3201–3210.

- Yang, K.; Wang, D.; Li, Y.Q. Distribution and Depression of the GABA(B) Receptor in the Spinal Dorsal Horn of Adult Rat. Brain. Res. Bull. 2001, 55, 479–485.

- Fukuhara, K.; Katafuchi, T.; Yoshimura, M. Effects of Baclofen on Mechanical Noxious and Innocuous Transmission in the Spinal Dorsal Horn of the Adult Rat: In Vivo Patch-Clamp Analysis. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2013, 38, 3398–3407.

- Kangrga, I.; Jiang, M.C.; Randić, M. Actions of (-)-Baclofen on Rat Dorsal Horn Neurons. Brain. Res 1991, 562, 265–275.

- Malcangio, M.; Bowery, N.G. Gamma-Aminobutyric AcidB, but Not Gamma-Aminobutyric AcidA Receptor Activation, In-hibits Electrically Evoked Substance P-like Immunoreactivity Release from the Rat Spinal Cord in Vitro. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1993, 266, 1490–1496.

- Ataka, T.; Kumamoto, E.; Shimoji, K.; Yoshimura, M. Baclofen Inhibits More Effectively C-Afferent than Adelta-Afferent Glutamatergic Transmission in Substantia Gelatinosa Neurons of Adult Rat Spinal Cord Slices. Pain 2000, 86, 273–282.

- Papon, M.-A.; Le Feuvre, Y.; Barreda-Gómez, G.; Favereaux, A.; Farrugia, F.; Bouali-Benazzouz, R.; Nagy, F.; Rodríguez-Puertas, R.; Landry, M. Spinal Inhibition of GABAB Receptors by the Extracellular Matrix Protein Fibulin-2 in Neuropathic Rats. Front Cell Neurosci. 2020, 14, 214.

- Désarmenien, M.; Feltz, P.; Occhipinti, G.; Santangelo, F.; Schlichter, R. Coexistence of GABAA and GABAB Receptors on A Delta and C Primary Afferents. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1984, 81, 327–333.

- Huang, D.; Huang, S.; Peers, C.; Du, X.; Zhang, H.; Gamper, N. GABAB Receptors Inhibit Low-Voltage Activated and High-Voltage Activated Ca(2+) Channels in Sensory Neurons via Distinct Mechanisms. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 465, 188–193.

- Dittman, J.S.; Regehr, W.G. Contributions of Calcium-Dependent and Calcium-Independent Mechanisms to Presynaptic In-hibition at a Cerebellar Synapse. J. Neurosci. 1996, 16, 1623–1633.

- Yang, K.; Ma, H. Blockade of GABAB Receptors Facilitates Evoked Neurotransmitter Release at Spinal Dorsal Horn Synapse. Neuroscience 2011, 193, 411–420.