Most cancer treatment modalities efficient in other malignancies display limited efficacy in pancreatic cancer, and novel therapeutic strategies in a multidisciplinary approach are highly warranted. Targeting the gut microbiota represents a big challenge for precision medicine in the near future. A growing body of evidence suggested the prognostic value of pancreatic tumor microbiome for cancer treatment efficacy. Pilot results showed that bacteria found in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) samples could modulate sensitivity to therapeutic agents via immune activation in the pancreatic tumor microenvironment. Thus, the microbiota-derived approach might represent an emerging trend for improving the immunotherapy and chemotherapy response in this devastating disease.

- pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- microbiome

- cancer treatment efficacy

- tumor microenvironment

- immune activation

- probiotics

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC), accounting for about 90% of all pancreatic cancer cases, is expected to become the second leading cause of cancer deaths before 2030 [1]. Since dense desmoplastic stroma represents one of the main factors responsible for the failure of currently applied PDAC treatment, focusing on the tumor microenvironment components might represent an option to overcome the chemoresistance and immune tolerance. Recently, the pancreatic microbiota has been recognized as an integral part of the PDAC microenvironment and the microbial remodeling of the tumor microenvironment towards immune tolerance might be associated with the inefficiency of antitumor immunotherapy. Thus, a microbiota-derived approach should also be taken into account and numerous clinical trials evaluating the effect of the microbiome in pancreatic cancer are currently ongoing (Table 1).

Oral gavage with fluorescently-labeled Enterococcus faecalis or Escherichia coli confirmed that gut bacteria were able to access the pancreas and might affect the pancreatic microenvironment. Amplicon 16S rRNA gene sequencing showed distinct stage-specific gut and pancreatic microbiome in tumor samples, inducing intratumoral immune suppression and PDAC progression. Furthermore, fecal transfer from PDAC-bearing mice contributed to disease progression. According to the results, deficiency in pattern recognition receptor (PRR) signaling slowed PDAC progression [2][3]. Activation of PRRs and TLR ligation by microbial lipopolysaccharides and flagellins in peritumoral milieu might promote tumor microenvironment reprogramming, and accelerate the PDAC tumorigenesis [4]. Moreover, modification of microbiome by oral antibiotic administration induced tumor microenvironment remodeling leading to a reduction in MDSC and an increase in M1 macrophage differentiation and intratumoral CD4+ and CD8+ T cell activation. Together, bacterial ablation enhanced antitumor immunity and increased susceptibility to αPD-1 immunotherapy by upregulating PD-1 expression on effector T cells in a PDAC orthotopic mouse model. Hence, a combination of specific microbiota ablation with checkpoint-directed immunotherapy might represent a potential treatment strategy for PDAC patients [4].

Gemcitabine is used as a key chemotherapeutic agent in the treatment of PDAC patients, therefore a deeper understanding of the mechanism of resistance would be of particular interest. Expression of the bacterial cytidine deaminase (CDDL) by intratumor Gammaproteobacteria was shown to be responsible for gemcitabine resistance in a mouse model of colorectal cancer due to the ability to metabolize the chemotherapeutic drug gemcitabine (2′,2′-difluorodeoxycytidine) into its inactive form (2′,2′-difluorodeoxyuridine). Moreover, cotreatment with ciprofloxacin has been shown to abrogate gemcitabine resistance. Interestingly, 16S rRNA sequencing of 65 human PDAC tumors identified Gammaproteobacteria (mostly members of Enterobacteriaceae and Pseudomonadaceae), as the most common bacterial taxa representing 51.7% of all reads. Geller et al. suggested the potential role of intrapancreatic microbiota in modulation of tumor resistance to gemcitabine, since cultivation of bacteria from 15 fresh PDAC tumors with colorectal carcinoma cell cultures mediated a complete resistance to a chemotherapeutic agent [5]. Discoveries from PDAC-bearing mice on gemcitabine-treated and nontreated controls revealed the substantial modifications in the gut bacterial composition. The shift towards an inflammation-related bacterial profile with increased Proteobacteria and Verrucomicrobia phylum is assumed to aggravate the pancreatic inflammatory state. Furthermore, bacterial translocation through the bloodstream or direct reflux through the pancreatic ducts might promote immune remodeling of the peritumoral microenvironment [6].

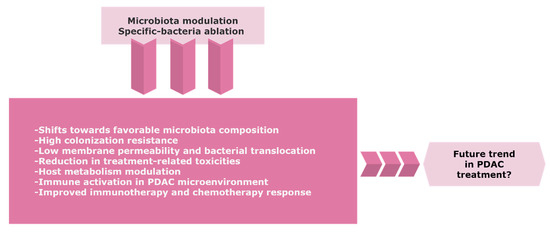

Re-establishing an effective intestinal ecosystem with a favorable enteric microbiota might increase the efficacy of cancer treatment (Figure 2). Despite the emerging role of the microbiome in PDAC, there is a limited number of controlled trials with a consistent design regarding the potential role of the gut and/or tumor microbiome modulation towards tumor progression or improving the sensitivity to therapeutics.

Figure 2. The possible trend of the gut and/or tumor microbiome modulation in PDAC. Precise targeting of microbiota composition might represent a novel approach to improve the therapeutic efficacy and clinical outcome for PDAC patients. Further research and randomized control trials with careful benefit-risk assessment are warranted due to the considerable risks of infection in immunosuppressive cancer patients. Abbreviations: PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

Oral antibiotics lead to an antitumor immune activation and restrained tumor burden in mice models bearing PDAC [7]. Coadministration of the PDAC drug gemcitabine with ciprofloxacin significantly reduced the level of detectable bacteria via in vivo imaging and improved the response to the chemotherapeutic agent in colon mouse models [5]. In addition, bacterial ablation via oral antibiotics was found to be protective in pancreatic tumorigenesis and to augment the sensitivity to immunotherapy [4]. Mohindroo et al. retrospectively analyzed the clinical data of 148 metastatic PDAC patients (135 patients exposed to antibiotics) showing prolonged OS and PFS (progression-free survival) after macrolide consumption longer than 3 days [8]. However, a retrospective single-center cohort study on resectable PDAC patients found that tetracycline treatment was associated with clinically significant decreased PFS and statistically significant worse OS [9]. Recently, the reanalysis of the comparator arm of the MPACT clinical trial (comprising 430 metastatic PDAC patients on antibiotic therapy) demonstrated increased gemcitabine-associated toxicity during and after antibiotic exposure [10].

Numerous studies highlight the positive effects of probiotics and prebiotics on gastrointestinal cancers through the activation of the host’s immune system, maintenance of intestinal barrier integrity, reduction in microbial activity by decreased intestinal pH, as well as inhibition of bacteria involved in the conversion of procarcinogens to carcinogens [11]. Probiotics are described as “mono- or mixed cultures of live microorganisms able to beneficially affect the host by improving the properties of the indigenous flora” [12]. Bacterial translocation is thought to be a possible route of communication between the gut and pancreatic microbiota. Hence, the effects of probiotic modulation in patients with pancreatitis have been evaluated as a risk factor for PDAC development. The first randomized, controlled, and double-blind study in a small cohort of 45 patients with severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) reported a significant reduction in pancreatic sepsis and the number of surgical interventions [13]. However, these results were not able to be reproduced in a second trial [14]. Importantly, the multicenter, randomized, and double-blind versus placebo PROPATRIA study, comprising 296 patients, reported that probiotic prophylaxis did not reduce the risk of infectious complications and was associated with an increased risk of mortality in patients with predicted SAP [15]. Moreover, the result of meta-analysis of six clinical trials found no significant effects of probiotics on the clinical outcomes of patients with SAP [16].

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) contains a greater quantity of microbiota than commonly used probiotic supplements and may represent a promising trend in overcoming the immunosuppression and resistance to therapy in cancer patients likely to have relatively short survival [17]. Animal studies suggest the protective effect of gut and tumor bacteria in PDAC patients who had survived more than 5 years without evidence of disease (long-term survivors). Mice that received FMT from patients with advanced disease harbored much larger tumors compared to the animals receiving FMT from long-term survivors of PDAC or healthy controls [18]. To evaluate the results from preclinical findings, the first clinical trial on resectable PDAC patients receiving FMT from healthy donors delivered through both colonoscopy and oral pills is in preparation.

Due to the contribution of microbiota to an enormous variety of metabolic and immunological pathways, the particular composition of patient´s microbiome should be taken into account to achieve the most efficient therapy response. According to recent studies, a combination of chemotherapy and immunotherapy with proper microbiota modulation might improve the efficacy of cancer treatment and outcome for PDAC patients.

Acknowledgments: The research was funded by the Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic and Slovak Academy of Sciences VEGA, project number 2/0052/18.

The article is from 10.3390/biomedicines8120565

References

- 1. Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, Rosenzweig AB, Fleshman JM, Matrisian LM.; Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 2913-21, 10.1158/0008-5472.

- Zambirinis, C.P.; Levie, E.; Nguy, S.; Avanzi, A.; Barilla, R.; Xu, Y.; Seifert, L.; Daley, D.; Greco, S.H.; Deutsch, M.; et al. TLR9 ligation in pancreatic stellate cells promotes tumorigenesis. J. Exp. Med. 2015, 212, 2077–2094, 10.1084/jem.20142162.

- Seifert, L.; Werba, G.; Tiwari, S.; Giao Ly, N.N.; Alothman, S.; Alqunaibit, D.; Avanzi, A.; Barilla, R.; Daley, D.; Greco, S.H.; et al. The necrosome promotes pancreatic oncogenesis via CXCL1 and Mincle-induced immune suppression. Nature 2016, 532, 245–249, 10.1038/nature17403.

- Pushalkar, S.; Hundeyin, M.; Daley, D.; Zambirinis, C.P.; Kurz, E.; Mishra, A.; Mohan, N.; Aykut, B.; Usyk, M.; Torres, L.E.; et al. The Pancreatic Cancer Microbiome Promotes Oncogenesis by Induction of Innate and Adaptive Immune Suppression. Cancer Discov. 2018, 8, 403–416, 10.1158/2159-8290.

- Geller, L.T.; Barzily-Rokni, M.; Danino, T.; Jonas, O.H.; Shental, N.; Nejman, D.; Gavert, N.; Zwang, Y.; Cooper, Z.A.; Shee, K.; et al. Potential role of intratumor bacteria in mediating tumor resistance to the chemotherapeutic drug gemcitabine. Science 2017, 357, 1156–1160, 10.1126/science.aah5043.

- Panebianco, C.; Adamberg, K.; Jaagura, M.; Copetti, M.; Fontana, A.; Adamberg, S.; Kolk, K.; Vilu, R.; Andriulli, A.; Pazienza, V.; et al. Influence of gemcitabine chemotherapy on the microbiota of pancreatic cancer xenografted mice. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2018, 81, 773–782, 10.1007/s00280-018-3549-0.

- Sethi, V.; Kurtom, S.; Tarique, M.; Lavania, S.; Malchiodi, Z.; Hellmund, L.; Zhang, L.; Sharma, U.; Giri, B.; Garg, B.; et al. Gut Microbiota Promotes Tumor Growth in Mice by Modulating Immune Response. Gastroenterology 2018, 155, 33–37.e36, 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.04.001.

- Mohindroo, Ch.; Rogers, J.E.; Hasanov M.; Mizrahi J.; Overman M.J.; Varadhachary G.R.; Wolff R.A.; Javle M.M.; Fogelman D.R.; Pant S., et al.; et al. A retrospective analysis of antibiotics usage and effect on overall survival and progressive free survival in patients with metastatic PC. J Clin Oncol 2019, 37, 15_suppl, e15781-e15781, .

- Hasanov, Z.; Ruckdeschel, T.; König, C.; Mogler, C.; Kapel, S.S.; Korn, C.; Spegg, C.; Eichwald, V.; Wieland, M.; Appak, S.; et al. Endosialin Promotes Atherosclerosis Through Phenotypic Remodeling of Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2017, 37, 495–505, .

- Corty, R.W.; Langworthy, B.W.; Fine, J.P.; Buse, J.B.; Sanoff, H.K.; Lund, J.L.; Antibacterial Use Is Associated with an Increased Risk of Hematologic and Gastrointestinal Adverse Events in Patients Treated with Gemcitabine for Stage IV Pancreatic Cancer. Oncologist 2020, 25, 579–584, 10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0570.

- Ciernikova, S.; Mego, M.; Hainova, K.; Adamcikova, Z.; Stevurkova, V.; Zajac, V.; Modification of microflora imbalance: Future directions for prevention and treatment of colorectal cancer?. Neoplasma 2015, 62, 345–352, 10.4149/neo_2015_042.

- Bengmark, S.; Ecological control of the gastrointestinal tract. The role of probiotic flora. Gut 1998, 42, 2-7, 10.1136/gut.42.1.2.

- Oláh, A.; Belágyi, T.; Issekutz, A.; Gamal, M.E.; Bengmark, S.; Randomized clinical trial of specific lactobacillus and fibre supplement to early enteral nutrition in patients with acute pancreatitis. Br. J. Surg. 2002, 89, 1103–1107, 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02189.x.

- Oláh, A.; Belágyi, T.; Pótó, L.; Romics, L., Jr.; Bengmark, S.; Synbiotic control of inflammation and infection in severe acute pancreatitis: A prospective, randomized, double blind study. Hepatogastroenterology 2007, 54, 590–594, .

- Besselink, M.G.; van Santvoort, H.C.; Buskens, E.; Boermeester, M.A.; van Goor, H.; Timmerman, H.M.; Nieuwenhuijs, V.B.; Bollen, T.L.; van Ramshorst, B.; Witteman, B.J.; et al. Probiotic prophylaxis in predicted severe acute pancreatitis: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2008, 371, 651–659, 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60207-X.

- Gou, S.; Yang, Z.; Liu, T.; Wu, H.; Wang, C.; Use of probiotics in the treatment of severe acute pancreatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit. Care 2014, 18, R57, 10.1186/cc13809.

- Pitt, J.M.; Vétizou, M.; Gomperts Boneca, I.; Lepage, P.; Chamaillard, M.; Zitvogel, L.; Enhancing the clinical coverage and anticancer efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade through manipulation of the gut microbiota. Oncoimmunology 2017, 6, e1132137, 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1132137.

- Riquelme, E.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Montiel, M.; Zoltan, M.; Dong, W.; Quesada, P.; Sahin, I.; Chandra, V.; San Lucas, A.; et al. Tumor Microbiome Diversity and Composition Influence Pancreatic Cancer Outcomes. Cell 2019, 178, 795–806.e712, 10.1016/j.cell.2019.07.008.