The demand for electricity is increased due to the development of the industry, the electrification of transport, the rise of household demand, and the increase in demand for digitally connected devices and air conditioning systems. For that, solutions and actions should be developed for greater consumers of electricity. For instance, MG (Micro-grid) buildings are one of the main consumers of electricity, and if they are correctly constructed, controlled, and operated, significant energy savings can be attained. As a solution, hybrid RES (renewable energy source) systems are proposed, offering the possibility for simple consumers to be producers of electricity. This hybrid system contains different renewable generators connected to energy storage systems, making it possible to locally produce a part of energy in order to minimize the consumption from the utility grid.

1. Introduction

Proper management of energy flow in MG (Micro-grid) systems must be carried out in order to improve the global performance of the system, to minimize the cost of the electrical bill, and to extend the lifetime of its components (e.g., converters, batteries, fuel cells). In general, energy management (EM) approaches involve an objective function, which could be used to maximize the efficiency of the hybrid RES system and to minimize energy consumption while improving the consumers’ quality of services. For instance, an EM control strategy that considers only the availability of the electricity can be developed to switch, at each time, from RESs (renewable energy sources) to storage devices or to the utility grid without considering the electricity price or the profitability of the system. In other cases, control strategies can interact with the generators by limiting the power generation. The aim is to ensure the electrical quality of services and, consequently, minimize the profitability of the installation. However, despite the ability of these strategies to reach the defined objective, they might decrease the performance of other criteria, such as the batteries’ lifetime, the system’s installation cost, and profitability.

Actual commercial inverters provide high-performance energy balance by interconnecting RESs, energy storage systems, and the utility grid, taking into consideration only a single-objective function. This later is mainly implemented in order to increase the availability of the electricity for building’s loads. With a limited configuration, the inverter can use batteries or the TEG at any moment without taking into account other constraints, such as the electricity cost and the C/D (charge/discharge) cycle of the batteries. For instance, high and frequent cycles of the C/D cycle of batteries could decrease their performance while reducing the system’s profitability. EM strategies that are deployed in the actual inverters use “if-else” statements to perform real-time decisions. For instance, the defined setpoint values (i.e., control inputs) cannot be adjusted according to predictive variations of RESs production, load demand, and battery SoC (state of charge). Such EM strategies are considered as “passive strategy” in their decisions and actions [

1]. Control strategies incorporating multiple-objective functions are therefore required for efficient energy management (i.e., ensuring electricity availability) while taking into consideration operational constraints (e.g., costs, reliability, and flexibility). In fact, “active strategies” for EM should be developed in order to adapt the setpoint values accordingly. These strategies could use intelligent and predictive control techniques together with recent IoT/Big-data technologies (e.g., data monitoring, data analysis, data mining, machine learning) for efficient EM in hybrid RES systems. In this work, control structures and strategies from the literature are presented by highlighting their advantages and drawbacks in the context of MG for smart buildings.

2. Control Architectures

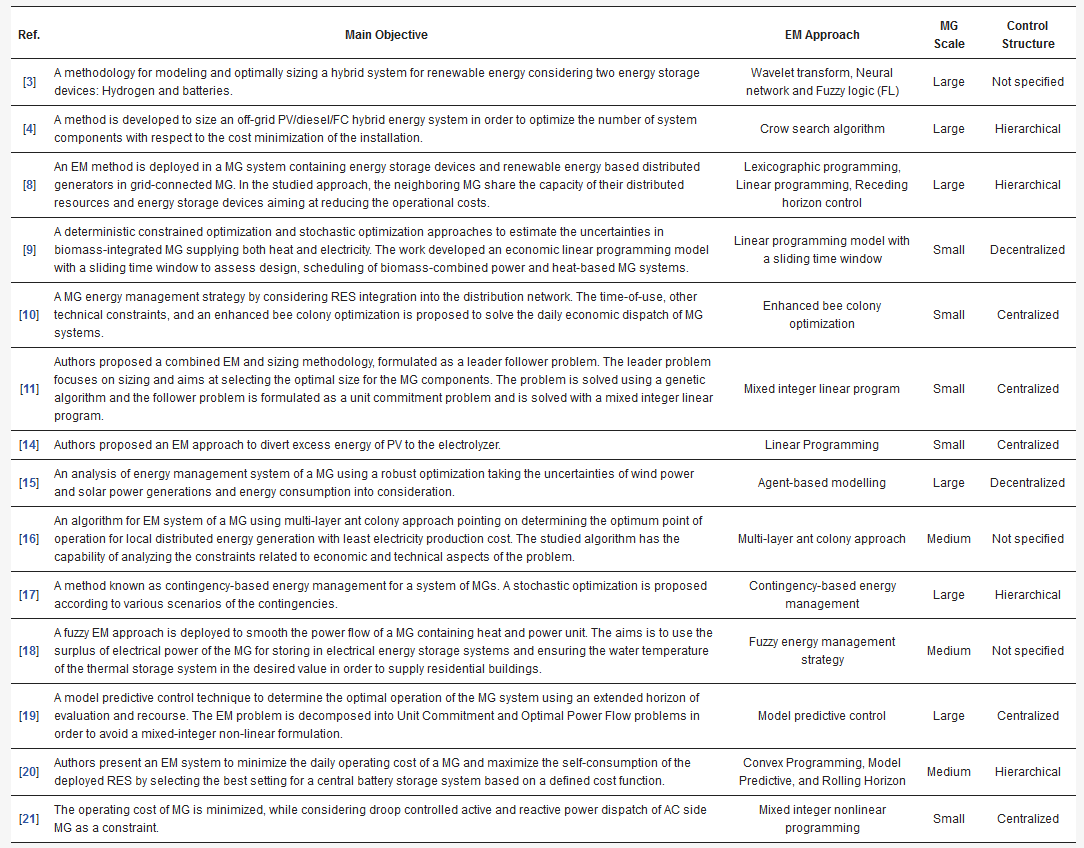

In hybrid energetic systems or MG systems, distributed and hybrid RES generators (e.g., PV (photovoltaic) panels and wind turbines) are used to produce clean energy (e.g., solar, wind), while energy storage systems are installed to compensate the fluctuation between RESs generation and load consumption. These hybrid systems can either operate on grid-connected or standalone modes depending on desired and fixed objectives. However, while the penetration of these distributed generators is continuously growing, new energy management approaches are required for their seamless integration within existing electricity network. presents resent literature works concerning the deployment of hybrid systems. As highly stated in , batteries are the most commonly used devices for energy storage.

Table 1. Survey through collection of EM (energy management) for the hybrid MG (Micro-grid) system.

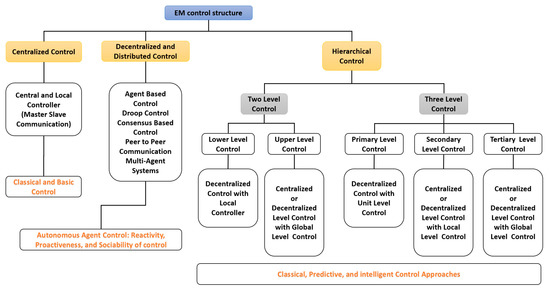

Therefore, the deployment of an energy management approach should be able to enhance the dynamic response of distributed energy resources under different operating conditions and maximize the usage of RES power generation while ensuring stability when one or more sources are connected or disconnected into/from the system. In this way, different approaches from the literature have been proposed for EM (). As shown in , the most suitable control strategies could be selected according to fixed constraints and objective functions. These control strategies can be classified into three main categories: Centralized, decentralized, and hierarchal control, as mentioned in . These control strategies are presented in the rest of this section.

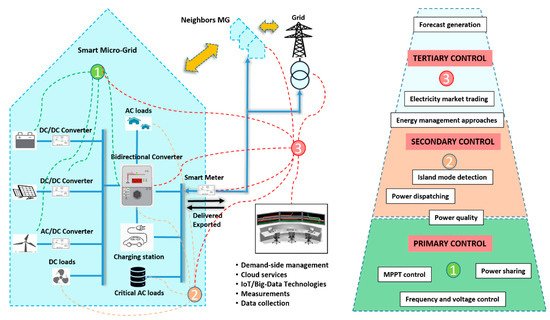

Figure 1. Control structure for energy management in MG systems.

Table 2. Survey through a collection of EM for the hybrid MG system.

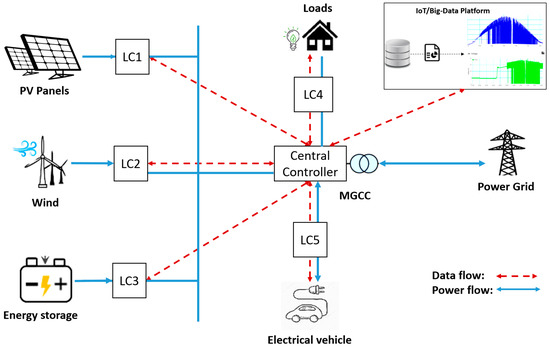

2.1. Centralized Control

Centralized control approaches use a single central controller (CC), which is characterized by a high-performance computing unit and a secure communication infrastructure in order to manage different entities of the system (e.g., RESs, storage systems, TEG). Each entity uses a local controller (LC) in order to communicate and directly interact with the CC. Moreover, using recent communication and computing technologies (e.g., IoT, Big-Data), the CC is able to monitor, collect, and analyze real-time data. This allows all entities to collaborate with the central EM controller while ensuring a flexible MG operation in both grid-connected and standalone mode (). The CC collects data, such as RES energy production, energy consumption pattern, the energy price from market operators, and weather conditions, and then executes the optimal and efficient system’s control.

Figure 2. Centralized control structure.

Numerous research works have developed and deployed centralized EM strategies. For instance, the authors of [

22] proposed a centralized controller in order to optimize the operation of MG by maximizing the production of distributed RESs generators while establishing back-and-forth energy transfer with the main utility grid. The efficiency of the proposed solution on the MG system was investigated by considering a typical case network operating under various market policies and spot market prices. Moreover, the authors of [

19] developed a centralized EM system for a standalone MG system based on the model predictive control method in order to reduce the computational loads. In fact, the studied problem was solved iteratively by nonlinear programming (NLP) and mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) techniques. Other centralized control strategies are summarized in . However, despite the ease of implementing the centralized strategies, they have shown their limits, especially when dealing with large-scale hybrid systems [

23].

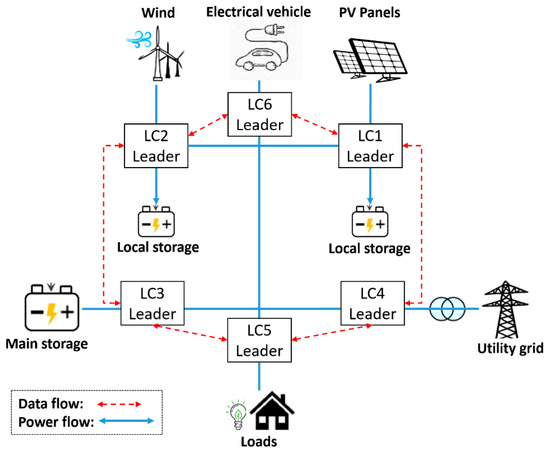

2.2. Decentralized Control

Unlike centralized strategies, in decentralized control, each entity is considered autonomous using an LC. This means that groups of entities are controlled separately by a leader. In literature, the terms ‘decentralized’ and ‘distributed controls’ are often used in place of each other [

24,

25]. The distributed control can be considered as a decentralized control in which LCs use local measurements, such as frequency and voltage values, to elect the leader entity. They are also allowed to share information with neighbors. For a distributed control, LCs do not only use local measurements but also are able to send and receive required information to other LCs [

26]. In decentralized control approaches, limited local connections are required and the control decisions are made based only on local measurements (). It does not require a high-performance computing unit and high-level connectivity [

27].

Figure 3. Decentralized control structure.

As depicted in , each LC operates individually on managed energy sources, storage systems, and loads without central control. The control decisions are determined locally based on local measurements, which are shared among controllers using peer-to-peer communication.

However, monitoring, processing, and data visualization are considered critical in order to coordinate various distributed controllers and achieve a global operation goal. This process is standardized by the norm IEC-61968 for a single-building energy management system and by IEC-61850 for interoperability between building MG systems [

28,

29]. Depending on the communication network availability, the decentralized control can be classified into three operation modes: (i) Fully dependent, in which the distributed controllers generate local control decision while communicating information with each other via a CC; (ii) partially independent, in which LCs communicate with each other and share information with the CC in order to generate central decisions; and (iii) fully independent, in which the distributed controllers communicate directly with each other and independently from the CC [

30]. However, despite the flexibility of these operational modes, the decentralized control structure presents low performance compared to centralized control [

25,

31,

32,

33]. This is due to the low response time and incomplete information about the total MG system installation.

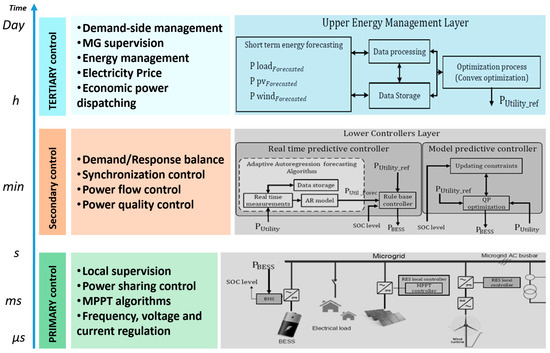

2.3. Hierarchical Control

Hierarchical control is mainly proposed for SG (smart grid) systems. In fact, the extended geographic areas of these systems and the extensive communication and computation requirements make the implementation of fully centralized approaches a difficult task. At the same time, the higher coupling between the different LCs requires a maximum level of coordination, which cannot be achieved by decentralized control structures. However, a compromise between the fully centralized and decentralized control structures is realized by providing hierarchical control structures [

34,

35] according to three control levels: Primary, secondary, and tertiary, as depicted in .

Figure 4. Hierarchical control structure.

The primary control level stabilizes the voltage and frequency generated from each source in order to respect the limits required by the standards [

36,

37,

38]. In addition, the primary control level detects the operating mode of MG systems, offering the ability to operate in grid-connected and standalone modes [

39]. For the secondary control level, the MG voltage and frequency are restored after the system’s load variation. The aim is to ensure and enhance the power quality within the required standards values, allowing the synchronization between the MG systems and the main electrical network [

40].

[1]The main objectives of tertiary control are the power flow control in the grid-connected mode, ensuring then the optimal operation in both modes like capacitance and inductance [

41]. includes the structures of each level of the hierarchical control. The control levels differ in the response time frame speed in which they operate as well as the infrastructure requirements, especially for the communication, which is normalized by the standards IEC 61850-7-420 and EN13757-4 [

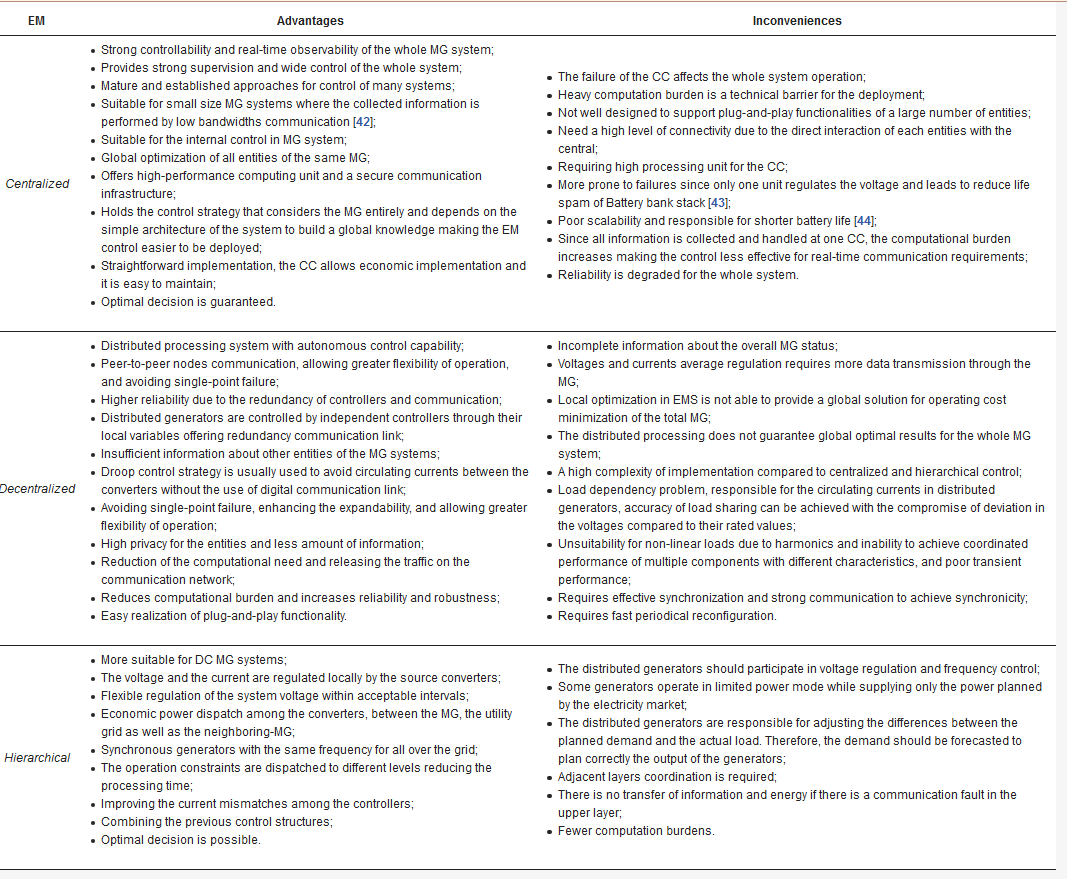

36]. The hierarchical control can be implemented in parallel in both centralized and distributed structure. The advantages and disadvantages of each control structure are presented in .

Figure 5. Hierarchical control levels.

Table 3. Control architectures for hybrid system, advantages and inconveniences.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/en14010168