Carbon-based Quantum dots (C-QDs) are carbon-based materials that experience the quantum confinement effect, which results in superior optoelectronic properties. In recent years, C-QDs have attracted attention significantly and have shown great application potential as a high-performance supercapacitor device. C-QDs (either as a bare electrode or composite) give a new way to boost supercapacitor performances in higher specific capacitance, high energy density, and good durability. This review comprehensively summarizes the up-to-date progress in C-QD applications either in a bare condition or as a composite with other materials for supercapacitors. The current state of the three distinct C-QD families used for supercapacitors including carbon quantum dots, carbon dots, and graphene quantum dots is highlighted.

- carbon

- quantum dots

- quantum capacitance

1. Introduction

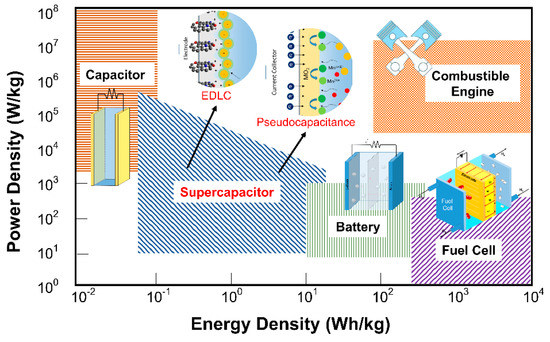

Fossil fuel shortages and environmental concerns regarding its uses for energy generation are among the most severe challenges in achieving sustainable development. Several critical parameters need to be achieved by those alternative energy storage devices, including high energy density, high power density, long lifecycle, environmental safety, and low cost [1,2,3]. To meet these critical parameters, the development of electrochemical-based energy storage devices (i.e., batteries and supercapacitors) still possesses fundamental research challenges [4]. The Ragone plot (Figure 1), utilized as a figure-of-merit of energy storage devices, shows that the supercapacitor performance lies between those of conventional capacitors and batteries [5]. Therefore, supercapacitors hold great prospect for future electronic systems such as Hybrid electric vehicles (EVs), memory backup systems, and portable electronic devices. [6,7,8]. In those systems, SCs can be integrated with primary high-energy batteries or fuel cells to provide temporary energy storage devices with a high-power capability. Nowadays, batteries are the primary energy storage for EVs. Nevertheless, in high cycle rate operations, batteries significantly heat up, which raises many safety concerns. On the other hand, high cycle rate operations also significantly decrease the capacity of batteries. These situations are in contrast with SCs that usually have significantly better cycling performance and durability for high rates of operations. However, SC still has a lower energy density than a battery. It is the real major challenge for the development and applications of SCs. We should overcome this problem by employing composite, doping, or other surface enhancements into materials.

In general, an SC comprises two electrodes that are immersed in an electrolyte. It may be electrically isolated by a separator, which can also play an essential role in SC performance. Based on the storage mechanism, SCs are classified into three types, i.e., the electric-double-layer capacitors (EDLCs), pseudocapacitors, and hybrid supercapacitors [9,10].

Figure 1. Ragone plot for several types of electrochemical energy storage devices: adapted from Reference [5]. Copyright American Chemical Society, 2004.

EDLC is the conventional supercapacitor in which capacitance arises solely from electrostatic charge accumulation between ions at the electrode/electrolyte interface [11]. This mechanism allows infinite time charge/discharge and is thus stable in the viewpoint of lifecycle stability. However, EDLCs suffer lower energy density than pseudocapacitors owing to limited specific surface area and the compatible electrode/electrolyte [12,13]. The most common electrode materials used in EDLC are porous carbon and its derivatives with large specific surface areas [14]. On the other hand, a pseudocapacitor relies on the reversible faradaic redox originating from the electroactive phases at the electrode/electrolyte interface. Even though it possesses high specific capacitance, a pseudocapacitor suffers challenging cycling stability because of its reversible faradaic redox process in the potential window [8]. Metal oxides, notably transition metal oxides, and conductive polymers are among the most common materials used in pseudocapacitors [15,16]. Another type is the combination of both the EDLC electrode and pseudocapacitive electrode in a single device with an intermediate SC performance. This device is a so-called hybrid supercapacitor. Based on the abovementioned energy storage mechanisms, numerous approaches have been extensively investigated to explore many different materials suitable for SC elements. Those approaches include nanostructuring and functionalizing the known electrode materials, designing materials by considering the energetic mismatch of electrolytes/electrodes, and exploring newly emergent materials [17].

Carbon-based Quantum Dots (C-QDs) emerged as materials that gained enormous scientific interest because of their unique properties [18,19]. This class of materials was firstly reported by Sun et al. in 2006 as carbon dots, owing to its nanometer-size diameter [20]. The carbon dots that were prepared from carbon nanotubes exhibited bright and colorful photoluminescence. These intriguing optical properties emerge from the quantum confinement effect, which typically occur in C-QDs with a diameter of around 10 nm [21]. However, some reports claimed that the quantum confinement effect was observed from carbon-based QDs with a larger diameter but less than 20 nm [22]. It should be noted that the occurrence of quantum confinement in this system is related to the significant increase in surface-to-volume ratio by reducing the C-QD diameter. The complex formation and structure of carbon-based QDs, which still largely remain unclear, make explanations of these material properties constrained and still debatable.

To date, several excellent review articles on the application of carbon-based QDs in energy conversion and storage applications, including solar cells, battery, thermoelectric devices, and supercapacitor, are reported [23,24,25]. However, they focus on the synthesis and the recent progress of C-QDs in applications broadly. To best our knowledge, there is a distinct lack of reviews mainly focusing specifically on Carbon-based QDs in supercapacitor devices.

The outstanding properties of C-QDs, i.e., their tunable electrical and optical properties, high stability, and excellent biocompatibility, not only correspond to the quantum confinement occurrence but also are due to variations in their structure and surface passivation [26,27]. There are various methods of producing C-QDs with different unique properties that lead this class of materials to become prospective for many applications such as optical devices, photocatalysts, sensors, and biomedicine [21,27,28]. Among the application avenues where the use of C-QDs might be distinguishable is its potential for components in electric and energy storage devices such as batteries and SCs.

2. Fundamental of Supercapacitor

2.1. Electric Double Layer Capacitor

Based on the electrical charge storage mechanism, supercapacitor devices are classified into three types: electric-double-layer capacitors (EDLCs), pseudocapacitors, and hybrid supercapacitors that combines both EDLCs and pseudocapacitors. Schematically, the mechanism behind each supercapacitor is shown in Figure 2a. EDLCs work via a phenomenon in which a charged object is placed inside a liquid. In the SC case, the liquid is an electrolyte, and the item is the electrode, which can also be a carbon-based material. The charges are stored electrostatically in the form of space charge accumulated at the electrolyte/electrode interface due to electric-double-layer formation. EDLCs can also be formed when a semiconductor is interfaced with a liquid electrolyte [29]. There are several models to simulate interface phenomena between charged electrodes and electrolytes. Helmholtz model is the simplest approximation to model charge distribution at a metal–electrolyte interface. The Helmholtz layer model is a well-known approximation and is the simplest model to explain charge distribution on the electrode/electrolyte interface [30]. This theory explains that the surface charge is neutralized by the opposite counterion situated at the surface. However, some phenomena are hardly explained with this theory alone since no rigid layers are formed on the surface, as described by this theory.

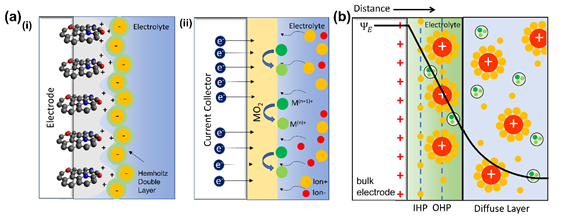

Figure 2. (a) Illustration of the Stern model for electrolyte ions on a charged electrode in (i) an electric-double-layer capacitor (EDLC) and (ii) a pseudo capacitance supercapacitor, as well as (b) a schematic model of ion distribution and mechanism.

Gouy-Chapman came up with a theoretical model that assumes that the opposing counterions are not rigidly attached to the surface but tend to diffuse into the liquid phase. The thickness of the resulting double layer is affected by the kinetic energy of the counterions. This model is named the diffuse double layer model. Boltzmann distribution is used to model the counterion distribution near the charged electrode [31,32]. Furthermore, Stern proposed a better model from the previous model by using finite ion sizes. The surface may also adsorb some ions in the plane to form another layer, which is now commonly known as the Stern layer [33]. The ions are absorbed by the electrode and form layers which can be distinguished into Inner Helmholtz Planes (IHPs, for specifically adsorbed ions) and Outer Helmholtz Planes (OHPs, for nonspecifically adsorbed ions) (Figure 2b). This current model of the EDLC extends to many fields and provides better approximations to the experimental results [10,34,35].

To date, many theories and simulations have been developed to understand better and to estimate the capacitance values of the electric-double-layer capacitors (EDLCs). In general, EDLCs can be assumed as a parallel-plate capacitor so that its capacitance can be approximated using the following equation:

where A is the surface area of the electrode, and d defines the effective thickness of the electric double layer (the Debye length). However, electrodes based on nanomaterials (e.g., nanowires, nanoparticles, nanotubes, quantum dots, etc.) have a high volume-to-surface-area ratio and different shapes of surface area. Consequently, another formulation is needed to rationalize the surface area of shapes and the formed pores.

Nevertheless, there is still an incomplete understanding of the real charge distribution on nanopore electrodes, although the available models explain how EDLCs store energy [36].

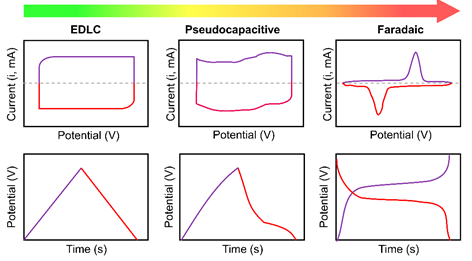

In an ideal EDLC, there are no faradaic and redox reactions on the electrode surface, which can be inferred from its cyclic voltammetry (CV) characterization, as shown in Figure 3 [37]. Without these electrochemical reactions, EDLCs have a more excellent lifecycle and are capable of a higher operation rate than pseudocapacitors. However, they have lower energy densities than pseudocapacitors. An ideal EDLC shows a vertical curve representing a capacitor in the equivalent circuit [38,39].

Figure 3. Schematic cyclic voltammograms and corresponding charge-discharge curves of electric-double-layer capacitor (EDLC), pseudocapacitor, and faradaic-type materials.

In EDLC electrodes, a high specific surface area (SSA) is an essential parameter that determines the ion accessible area. Carbon-based materials like carbon nanofibers [43], activated carbon [44], and few-layer graphene [18] are other carbon allotropes promising for EDLC supercapacitor electrodes [44] owing to their large surface area. A significant capacity improvement could be achieved easily by controlling the interlayer interaction [45,46,47,48]. Enhancing the electrical conductivity in those materials might be achieved by optimizing elemental doping in addition [47,48].

2.2. Pseudocapacitor

Pseudocapacitors store charges using redox or faradaic reactions that involve high-energy electrode materials, as shown in Figure 2a. The reaction is less similar to the reaction in battery materials, pseudocapacitance can be distinguished by the quick redox reaction on the surface or near-surfaces of electrodes [49]. The reaction mechanism of the pseudocapacitive system is illustrated in Figure 2b, which is predicted to fill the gap between EDLCs and batteries. A broader voltage window is allowed in pseudocapacitance since the surface redox mechanism is mainly controlled by its charge storage mechanism [50]. Combining pseudocapacitive materials, conductive materials, and the capacity from its EDLC performance is common in SCs [44,51].

Cyclic voltammetry (CV) is a standard method for determining the electrochemical properties in SC; therefore, it can distinguish the behaviors of different types of SCs. A typical CV measurement of pseudocapacitors (Figure 3) shows a broad redox peak that exhibits small peak-to-peak separation instead of a rectangular-like shape. The broad redox peak is proof of the reduction process that happens inside pseudocapacitive materials. At the same time, the rectangular-like CV characteristics are typically found in SCs with exclusively electrostatic processes, such as in EDLC [52,53].

Supercapacitor face similar crucial challenges in increasing energy density for energy storage applications. In the capacitor, the energy stored inside is determined by capacitance and voltage, as . We can increase the stored energy density effectively either by improving the capacitance of the materials or by increasing the cell voltage [12]. Increasing the cell voltage of pseudocapacitive materials can be achieved by changing the utilized electrolyte [55].

The electrolyte and electrode are the two crucial parts that affect the SC directly. Conductive polymers, metal chalcogenides, and transition metal oxides are the most common materials used for pseudocapacitance SC electrodes. Their wide voltage window and high specific capacity values are supposed critical factors in high pseudocapacitance SC performances [56,57,58,59,60,61,62]. Various methods are used to synthesize SC electrode materials, such as sol-gel, electropolymerization/electrodeposition, in situ polymerization, vacuum filtration technique, chemical vapor deposition (CVD), co-precipitation, hydrothermal, and others. Optimizing the parameters of various synthesis methods is vital to obtained best supercapacitor performances [8,52,63,64].

Despite its numerous reports, transition metal oxides and chalcogenides still suffer low conductivity or high internal resistance that are detrimental to the SCs’ high cycling rates capabilities. A composite of these pseudocapacitive materials with carbon-based materials is one of the best options to overcome these issues [65,66].

A new concept to increase capacitance has emerged since nanostructurization materials lead to modification of their electronic energy structure. Most notably, quantum confinement effects in 2-dimensional (2D) materials, 1-dimensional (1D) materials, and 0-dimensional (0D) materials give rise to the formation of abrupt changes in their electron density-of-states. In 1D materials, it is manifested by Van Hove singularity. The ability to fill the van Hove singularity of 1D materials and the discrete energy level of 0D QD materials may lead to enormous capacitance. It is known as quantum capacitance [68,69,70]. This quantum capacitance is an essential factor that influences both the total capacitance and the EDLC performance [71].

3. Properties and Preparation of Carbon-Based Quantum Dots (C-QDs)

Carbon-based Quantum Dots (C-QDs) are one class of emerging nanomaterials that are mainly investigated for their photoluminescence properties. Surprisingly, C-QDs have also been reported remarkable electrochemical properties and could be applied for diverse energy storage applications. Thus, in this section, the structural and electrical properties of C-QD materials will be elaborated, especially the aspects attributed to energy storages device performances. Furthermore, the preparation of C-QDs directing the structural and electrical properties of C-QDs was also elaborated systematically.

3.1. Structural Properties

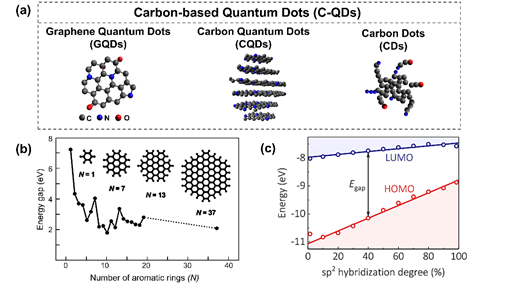

Carbon-based QDs refer to a zero-dimensional fragment that was dominantly by carbon atoms [18]. Their size is on the scale of a few nanometers, and they exhibit some unique properties. In this review, the terminology C-QDs is used to describe all kinds of carbon-based materials that experience these size-dependent effects. These effects are either from the real quantum confinement effect or from the formation of electronic energy states due to emerging structures on the C-QD surface. Based on the complexity of their formation and structures, the terminology carbon-based QDs is categorized into three different terms, as proposed by Cayuela et al. (Figure 4a) [72]: carbon dots (CDs), carbon quantum dots (C-QDs), and graphene quantum dots (GQDs). These carbon-based QDs terms were classify based on the arrangement of carbon atoms, the crystalline structure, and dimensionality.

3.1.1. Carbon Dots (CDs)

The term Carbon Dots (CDs) or Carbon Nanodots was proposed to identify the amorphous quasi-spherical nanodots that still lack quantum confinement [73]. Although CDs have a nanometer-size diameter in the range 1–20 nm, the quantum confinement phenomenon was not observed. Thus, the electronic bandgap of CDs did not strongly depend on its size. This term was also attributed to carbon-based polymer dots that exhibit typical photoluminescence properties in the range of nanometers [74]. CDs are mainly composed of an sp3 hybridization carbon core with a small domain of sp2 hybridization. In some cases, the X-ray diffractometer results of the CDs show the typical graphite peak centered at approximately 20° dominated by sp3 hybridization. Surprisingly, it was reported computationally that the hybridization degree of CDs plays a crucial role in bandgap engineering of CDs [75,76]. Thus, the optical and electronic properties of CDs rely on the surface functional groups that can easily be modified through a preparation method.

3.1.2. Carbon Quantum Dots (C-QDs)

Carbon Quantum Dots (C-QDs) refer to spherical carbon nanosized with a crystalline structure and show the quantum confinement effect. C-QDs are a quasi-spherical particle with lateral and height size ranges of 1–20 nm [73]. The lattice constant of C-QDs lies between that of a graphene lattice and that of a graphite lattice [77,78,79]. However, the C-QDs have lower crystallinity than GQDs owing to the less crystalline sp2 carbon [80]. In most cases, C-QDs are strongly associated with surface passivation. Thus, both the quantum confinement effect and the surface functional groups contribute to C-QDs’ bandgap energy.

3.1.3. Graphene Quantum Dots (GQDs)

Graphene Quantum Dots (GQDs) refer to 0D graphene sheets in a nanoscale dimension that exhibit strong quantum confinement [72]. Consequently, GQDs have good crystallinity with the lattice constant of graphene [18,81,82]. GQDs are dominated by the π-conjugate sp2 carbon structure, a fingerprint of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon molecules. Distinct from the pristine graphene, GQDs may consist of several layers of graphene sheets of 1–10 nm size. However, the mechanism of the edge site effect and the atomic doping (especially nitrogen) effect on GQDs have been considered similar to that of the graphene structure [81,83]. GQDs also could be enriched by the various surface functional groups as well as C-QDs.

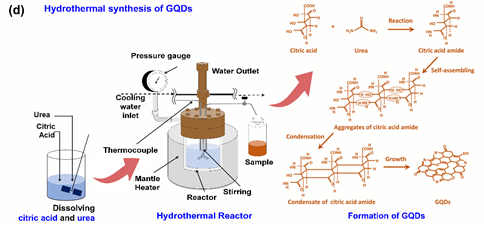

Figure 4. (a) Classification illustration for carbon-based quantum dots: adapted from Reference [72]. Copyright Royal Chemistry Society, 2016. (b) The energy gap of Graphene Quantum Dots (GQDs) as a function of the number of aromatic rings from a DFT calculation: reproduced from Reference [83]. Copyright John Wiley & Sons, 2010. (c) Highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO)−lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energy gap of Carbon-based Quantum dots (C-QDs) as a function of the hybridization degree of the C−QDs’ domains: reproduced from Reference [76]. Copyright American Chemical Society, 2019. (d) The hydrothermal method for preparing the GQDs and the proposed mechanism of GQDs that were synthesized from citric acid and urea: reproduced from Reference [84]. Copyright Royal Chemistry Society, 2014.

Considering the SC’s electrode requirements, the edge site of the GQDs and the surface functional groups of all C-QD types enhance the SC’s performances. Specifically, the edge sites of GQDs could enhance the electric conductivity of GQDs owing to the doping effect of dangling bonds, the adsorption of ionic charges, and the formation of EDL capacitance [85,86,87].

3.2. Electronic Properties

The electronic transport properties of carbon-based QDs depend on the complicated interplays among representative electronic energy states of the carbon cores, the surface functional groups, the available heteroatom dopants, and the electronic couplings between neighboring nanoparticles [94,95]. Conventionally, efficient electron transfer is expected to originate from the arrangement of the high crystalline structure of carbon-based QDs that are free from any intrinsic defect. Among the different types of carbon-based QDs, GQDs are the most promising for better electron transfer than CDs and C-QDs due to the higher degree of orders within their core. However, some of the functionalization of these GQD edge sites can be destructive. They may create electron trap sites, hindering electron transfer [87]. In C-QDs, the -electron network that occurs from the sp2 hybridization may function as electron acceptors/donors, as a conducting medium for electron transport, or as bridges for electron transfer [73]. The use of C-QDs can be essential in preventing the decrease of electron conductivity after cycling due to cracking of the primary materials [100]. Moreover, a C-QD’s charge carrier mobility also depends on its ligand length [101].

3.3. Preparation of Carbon-Based Quantum Dots

Numerous reports on the preparation of C-QDs through various methods have been reported extensively. Generally, the preparation method of C-QDs is classified into two categories: “top-down” and “bottom-up” approaches.

3.3.1. Top-Down Approach

The top-down approach includes the laser ablation, chemical oxidation, chemical exfoliation, arc-discharge, and ultrasonication methods [104,105,106]. In the laser ablation method, a nanosecond-pulsed laser with a specific wavelength is directed at a target. Dense plasma is obtained from the interaction between the laser and the target. The precursor solution and/or nitrogen, which serve as dopant atoms, induce a spontaneous plasma cooling process. The C-QDs are then produced through physical shearing of the carbon structure of the target and by incorporating the dopant atoms from the precursor solution. Nitrogen, oxygen, and sulfur doped on C-QDs were reported successfully prepared through this method [104,107,108].

3.3.2. Bottom-Up Approach

The bottom-up approach basically produces the C-QD structure from smaller carbon-based molecules through a chemical and physical reaction. This approach includes hydrothermal synthesis, microwave synthesis, and pyrolysis [84,111,112]. Furthermore, this technique is preferable for large-scale production due to its ease of use, environmentally friendliness, and low cost compared to other preparation methods. Our group has developed various C-QDs from citric acid and urea as raw materials via a hydrothermal method since 2014 [81,84,111,113,114]. Based on a comprehensive analysis, the GQDs are formed by dimer or oligomer-sized aggregates of citric acid amide that condensate into nanostructure graphene-like sheets (Figure 4d) [84]. A further systematic study revealed that the carbon–nitrogen configuration on the GQD structure plays an essential role in controlling its optical properties [81].

4. Recent Progress of Bare Carbon-Based Quantum Dots for Supercapacitors

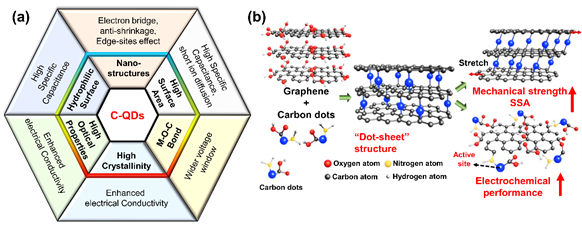

Owing to C-QDs’ superior properties, C-QDs can be applied in different types and elements of supercapacitors. Both electrode and electrolyte elements can utilize C-QDs as building blocks. This section summarizes the recent progress in the literature on the utilization of bare C-QDs as the electrode in supercapacitors. In general, C-QDs exhibit the capacitive behavior of an EDLC mechanism. However, recently, the use of C-QDs has also been reported to be beneficial for pseudocapacitors. Overall, we summarize the figure of merit of C-QDs in Figure 5a.

Figure 5. (a) A schematic showing the figure-of-merits of C-QDs composites for Supercapacitor (SC) applications that should be pursued and (b) a schematic illustration of the dot-sheet porous structure that consists of graphene and carbon dots: reproduced from Reference [115]. Copyright Royal Chemistry Society, 2018.

In bare C-QD SC electrodes, GQDs are more commonly used since they show good conductivity and edge-state-related properties that result in decent specific capacitance. On the other hand, the other types of C-QDs must be combined with high conductive materials to ensure high performance of the supercapacitor. Qing et al. introduced the combination of enriched carbon dots with graphene microfibers to produce high-performance supercapacitors [115]. The CDs, which contain abundant functional groups, also contribute to the capacitance due to active electrochemical activity, which may lead to the existence of quantum capacitance [115,116].

Hypothetically, the GQDs could improve the conductivity of any electronic devices based on the superior properties of GQDs, including their high specific surface area, active edge site, and the C-QDs that preserve abundant free electrons in the system. However, this amine-enriched GQD electrode system still needs further investigation to clarify the electron transport mechanism [93].

5. Recent Progress of Carbon-Based QD Composites

5.1. Carbon Dot Composites

Carbon dots (CDs), as one class of C-QDs, are distinctive among other C-QDs. They have a lower degree of crystallinity. However, CDs have various emerging properties when combined with the other materials for SC applications. Initially, the use of carbon dots as tandem materials in SC aimed to exploit their surface functionalization to increase SC performances. As they have a lot of hydrophilic functional groups on the surface, CDs can increase the electrodes’ wettability [132]. Furthermore, CDs also may increase the active surface area, provide unique morphology, and modify the conductivity.

Combining transition metal chalcogenides with CDs can be done by co-synthesizing them using the hydrothermal method [67]. The existence of CD in metal oxide and metal chalcogenides might significantly alter the structures. The porous structure results in better penetration of the electrolyte into the electrode [135]. Others also reported that the presence of carbon inside the synthesis process when creating CD-containing composites also changes the structure of the materials [136,137].

By varying the concentration of CDs, the nanostructure morphology of NiCo2O4 changes significantly [133]. These distinguished morphologies provide the divergent type of specific surface area that results in distinct specific capacitance values of each composites as well as cycling durability. The improvement in the dielectric coefficient can give us a benefit in increasing the EDLC performance.

5.2. Carbon Quantum Dot Composites

In C-QDs/metal oxide, the C-QDs were utilized as bridges to connect oxide material domains. In MnO2 [148] matrices, the C-QDs not only improved the specific capacitance but also broadened the potential window of the composite for SC operation [92]. There are three possible noncovalent approaches between the C-QDs and the polymer semiconductor: π−π stacking interaction, van der Waals interaction, or electrostatic interaction [162]. The formation of π−π conjugation between the polymer and C-QD surface provides significant conductive electron transfer due to the lower energy interfaces.

The formation of rough or porous structures in the conductive polymer after adding C-QDs increased the surface-to-volume ratio of the materials. The wider surface area can provide extra ion storage, resulting in high capacitive performance. From structural perspectives, the structural enhancement in transition metal oxides by the introduction of C-QDs also facilitates higher electrical and modification of ionic movement for the composite [143,144]. The hydroxyl groups on C-QD surfaces also have a role as electron donors and strong reductants [73,163]. Therefore, further advancements are needed, such as through the addition of doping using other materials or modification of the C-QD composite using GQDs that provide better structural stability [159,164].

5.3. Graphene Quantum Dot Composites

Combining transition metals with sulfide is known to provide higher pseudocapacitive performance in SC applications compared to transition metal oxide. Nevertheless, they also suffer from the same problems that arise in transition metal oxides, such as low electron transportability and quick capacity decay at high charging–discharging rates. A combination of transition metal sulfide with GQD can lower resistance at the electrode and electrolyte interface [82].

Exploitation of the GQD edge properties can be utilized to increase the SC properties of other materials. GQDs have abundant -conjugation and edge sites, which make it possible to increase properties like conductivity, surface area, and wettability [157]. The unique homogenous edge states of GQDs can be the host sites for free electrons. Free electrons accumulated at the edge can form an extra electrostatic attraction, which increase the specific capacitance [156]. Another benefit of GQD usage in a composite is the formation of the M-O-C (M = metal) covalent bond at the interface of the GQD species and the metal oxide hosts [148,156,165]. In some materials M-O-C bonds became the origin of the increased capacity retention in the corresponding SC devices. The strong bond of M-O-C could also act as new active sites for a redox reaction [165].

6. Challenges and Future Perspectives

C-QDs are promising candidates for the next generation of supercapacitors. Owing to its simple synthesis, high conductivity, and charge donor ability, some C-QDs have been successfully reported to be used as electrodes and electrolytes in SC devices. C-QD-based supercapacitors face many substantial challenges such as:

-Requirement for deep understanding of the charge storage mechanism in C-QD-based electrodes.

-Diversification of synthesis, purification, and functionalization routes of C-QDs.

-Enhancement of the performance-to-fabrication cost ratio.

6.1. Wearable Supercapacitors

Now and in the near future, energy storage devices should fit and conform to different structures and shapes (e.g., human/animal bodies, plants, and soft robots) since applications will not only be limited to a planar place. There are various properties of C-QDs that made them remarkably attractive for applications. The C-QD matrix in composites allows some other material combination also to have good flexibility. Recently, several composites of C-QD materials have demonstrated outstanding flexibility with excellent bending capabilities of more than 90° but without changing the electrochemical performance after bending [151,153].

6.2. Quantum Capacitance Supercapacitor

Another emerging outlook on how to significantly enhance the supercapacitor capacity in nanostructured materials, including C-QD, is by looking into possibilities to exploit the quantum capacitance effect. Complementing our understanding of the working mechanism with quantum mechanics insight would give us a whole new perspective in designing materials for supercapacitors, particularly those involving nanomaterials. The material’s capacitance microscopically and strongly depends on the so-called electronic density-of-states (DOS) of the materials. In classical 3-dimensional bulk materials, the DOS for each electronic state is continuous. In this case, the geometric capacitance is much more dominant in limiting the capacitance value rather than filling these continuous energy levels.

6.3. Self-Charging Supercapacitor

The charging mechanism of a supercapacitor allows us to charge it with abundant energy sources available in nature, like light, thermal, vibration, or even gravitational energy [185,186,187,188]. In the thermal harvesting device family, the potential to have a Soret effect occurring in the electrolyte of the supercapacitor is attractive since it can be compared with having a high Seebeck coefficient in a thermoelectric device. The Soret effect dictates that temperature differences generate an ion concentration gradient due to thermo-diffusion on ions in the electrolyte [189,190]. Consequently, these ions can accumulate at the interface of the electrolyte/electrode as in a supercapacitor. In the Soret effect, connecting to an external load is not as easy as in traditional thermoelectricity due to the blocked thermo-diffusion ion on the metal surface.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/nano11010091