Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a prevalent neurodegenerative disorder, which relates to not only motor symptoms, but also cognitive, autonomic, and mood impairments. The literature suggests that pharmacological or surgical treatment has a limited effect on providing relief of the symptoms and also restricting its progression. Recently, research on non-pharmacological interventions for people living with PD (pwPD) that alleviate their motor and non-motor features has shown a new aspect in treating this complex disease. Numerous studies are supporting exercise intervention as being effective in both motor and non-motor facets of PD, such as physical functioning, strength, balance, gait speed, and cognitive impairment. Via the lens of the physical profession, this paper strives to provide another perspective for PD treatment by presenting exercise modes categorized by motor and non-motor PD symptoms, along with its effects and mechanisms. Acknowledging that there is no “one size fits all” exercise prescription for such a variable and progressive disease, this review is to outline tailored physical activities as a credible approach in treating pwPD, conceivably enhancing overall physical capacity, ameliorating the symptoms, reducing the risk of falls and injuries, and, eventually, elevating the quality of life. It also provides references and practical prescription applications for the clinician.

- Parkinson’s disease

- Parkinson’s disease dementia

- physical activity

- motor disorders

- quality of life

- prescription

Each exercise type helps train different muscle groups, so, for pwPD, integrated training is the key prescription. One shall not favor any particular type and neglect the interlocking relationships between each exercise type.

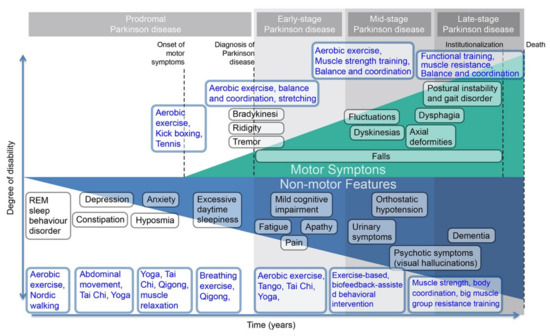

Figure 1 aggregates the time and degree of disability pwPD suffer; along the way, this paper suggests compatible recommended exercise to alleviate each motor or non-motor features. There are four different stages shown in Figure 1. Non-motor features occur in the very beginning phase throughout the progress and then the motor symptoms in the prodromal stage. The severity of both motor symptoms and non-motor features shown in the y-axis increases as the stage of PD progresses, where motor symptoms appeared as an upward line and non-motor features appeared as a downward line.

Various symptoms across the stages of PD have corresponding exercise suggestions presented in the vertical section of each symptom. For example, pwPD with bradykinesia, rigidity, and tremor can be treated with PA, such as cardiovascular, balance and coordination, and stretching. Significant studies that conducted RCTs on patients with early- and mid-stage PD indicate the benefit of aerobic exercise on reducing PD symptoms and improving cardiovascular fitness and long-term aerobic endurance [17,18]. Consequently, aerobic exercise is shown as being corresponding to early- and mid-stage PD in Figure 1. With the integration of corresponding exercise and original figure from the study, Parkinson disease, from Poewe et al., Figure 1 visually presents a PD symptoms timeline with exercise treatment [19].

Figure 1. People living with PD (pwPD) symptoms timeline. REM—rapid eye movement.

Exercise for Motor Symptoms

This paper strives to provide exercise insights for pwPD. Table 1 and Table 2 below indicates the suggested exercise modes for motor and non-motor features of PD.

For targeting PD’s motor symptoms such as freezing of gait, motor skill dysfunction, weak muscles, imbalance, and rigidity, different exercise modes are listed for improvement. A recent study about exercise strategy for motor symptoms of PD, focusing on gait and balance, clearly suggests that there are seven kinds of exercise which may improve gait and balance, including muscle strength training, aerobics, cueing exercise, gait training, balance training, Tai Chi, and dance [20,21].

Table 1. Exercise mode and improvement for motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.

|

Symptom |

Exercise Mode |

Improvement |

References: Grade 2 |

|

Freezing of gait |

Running, Swimming, Cycling, Hiking, Aerobic dancing, Jogging |

Walking speed↑ 1 Step and stride length↑ Motor performance↑ Cadence↑ Cardiovascular endurance↑

Balance↑ Weight shifting ability↑ Movement control↑ Trunk rotation↑ Multidirectional stepping ability↑ Maintenance of postures↑ Walking speed and steps↑ |

[21]: A, [22]: C, [23]: C, [24]: B, [25]: D, [26]: A |

|

Motor skill dysfunction |

Kick-boxing Playing tennis Push-ups and pull-ups Calf raises |

Cardiovascular endurance↑

Stretch and calf muscle strength↑ |

[21]: A, [27]: A, [28]: A, [29]: B, [30]: B, [31]: A |

|

Weak muscles |

Lunges and bicep curls using dumbbells Weight training High-intensity interval training Functional training, Eccentric training, Interval training Sprinting training Mid back squeezes Planks Squats

|

Muscle strength↑

Muscle strength↑

Back muscle strength↑ Core muscle strength↑ Core and thigh muscle strength↑ Core and whole body muscle strength↑ Core and thigh muscle strength↑ |

[32]: D, [33]: C, [34]: A, [35]: B

|

|

Imbalance |

Standing on one foot, BOSU ball 3 movements Brisk walking Tai Chi

|

Balance↑

Weight shifting ability↑ Movement control↑ Trunk rotation ability↑ Multidirectional stepping↑ Maintenance of postures↑ Dynamic balance↑ Backward walking↑ Turning and Multitasking skills↑ Walking speed and steps↑ |

[20]: A, [22]: C, [23]: C, [36]: D |

|

Rigidity |

The shimmy 4

Yoga Rotation

Hamstring stretch Hip flexor stretch Calf stretch Shoulder shrugs Chin tucks |

Coordination and relaxation↑ Core strength and body strength↑ Body balance and coordination↑ Stretching↑ Body balance and coordination↑ Coordination↑ Stretching↑ Muscle relaxation↑ Stretching↑ Stretching↑ Stretching↑ Stretching↑ Neck stiffness improvement↑ |

[27]: A, [37]: A, [38]: A, |

1 “↑” represents increase; “↓” represents decrease. 2 The level of evidence of each reference is graded as A: overwhelming data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs); B: quasi-experimental design; C: results stem from uncontrolled, nonrandomized, and/or observational studies; D: review or evidence insufficient for categories A to C. 3 BOSU stands for Bionic Oscillatory Stabilization Unit, which is an inflated rubber hemisphere device using for balance training. 4 A dance move that requires shoulders quickly alternated back and forth with body holding still.

Cueing Strategies

Even though recent systematic reviews could not gain concrete evidence supporting the efficacy of physiotherapy in PD due to methodological problems in some studies, reviewers did state that additional cueing techniques could improve the efficacy of physiotherapy [39]. Cueing is described as using a piece of information or stimuli to aid or facilitate movement initiation. Recent reviews on cueing reveal that it can have an immediate and supreme effect on gait performance in pwPD, such as improvements in walking speed and steps [40]. For instance, cycling is demonstrated as a useful approach as exercise training in pwPD who are grounded by severe freezing of gait [22]. Moreover, recent studies even observe an improvement of freezing of gait by applying nonexternal cues, which are imagining and mimicking bicycling by pwPD [23].

Previous laboratory experiments have shown the influence of cueing in single-session results in a short-term correction of gait; however, if carry-over to un-cued performance and activities of daily living (ADL), the influence is limited [41]. It becomes very complex when experimenting cues in therapeutic settings, as each individual pwPD has different triggers of cue delivery, such as visual, auditory, or somatosensory, and the cue parameter adopted for movement correction such as frequency or size of step. Despite the fact that there are two studies mentioning the retention effects of cues, the training effects and the clinical application of cues for improving walking and gaits have not been discussed and evaluated in other work. Besides, issues such as being distracted, which may lead to increasing the risk of falling, have risen while applying cues.

External cues are used as effective interventions aiming to improve motor performance, especially gait [24]. In order to improve pwPD’s everyday motor tasks, cognitive movement strategies present mental techniques by teaching the pwPD to separate complex motor sequences in series of single and simple movements that are to be performed in a correct and unchanged order. This strategy aims to offer motor performance as a conscious task, meanwhile avoiding multi-tasking, which also bypasses the defective basal ganglia. Balance training is another pivotal part, which links tightly with fall prevention. Additionally, improving physical capacity with aerobic training, flexibility, and strength exercises may reduce symptoms and improve pwPD’s general well-being and quality of life.

Exercise for Non-motor Features

Table 2 is a classification by PD’s non-motor features, which provides insight for which exercise can assist with PD non-motor features, along with the improvement effects.

Table 2. Exercise mode and improvement for non-motor features (except cognitive dysfunction) of Parkinson’s disease.

|

Symptom |

Exercise Mode |

Improvement |

References: Grade 4 |

|

Constipation |

Physical therapy incorporating abdominal massage 1 |

Abdominal movement range↑ 2 |

[42]: D, [43]: B, [44]: C |

|

Depression |

Tai Chi, Yoga |

Flexibility↑ 3 |

[27]: A, [45]: A, [46]: A, [47]: B |

|

Drooling |

Expiratory muscle strength training |

Muscle strength↑ |

[32]: A, [48]: A, [49]: D |

|

Fatigue |

Tango, High-intensity exercise training |

Blood circulation↑ Metabolism↑ |

[50]: A, [51]: D, [52]: B |

|

Orthostatic hypotension |

Leg-holding exercises |

Circulation↑ |

[33]: C, [42]: D |

|

pain |

Tai Chi, Breathing exercises, Yoga |

Flexibility↑ Resistance↑ Balance↑ |

[27]: A, [37]: A, [38]: A, [45]: A, [46]: A, [53]: D, [54]: D |

|

Psychosis (hallucinations or delusions) |

Aerobic exercise, Yoga |

Focus↑ Cardiovascular↑ Muscle strength↑ Body coordination↑ |

[33]: C, [34]: A, [35]: B |

|

Sexual dysfunction |

Qigong, Cycle ergometer exercise training |

Focus↑ Depression symptoms↓ |

[46]: A, [55]: A, [56]: D |

|

Anorexia, nausea, vomiting |

General exercise |

Neural apoptosis↓ Neurodegeneration process↓ PD development and symptoms↓ |

[57]: D, [58]: D, [59]: D |

|

Sleep problems |

Nordic Walking Aerobic training Weight lifting exercise Yoga |

Muscle strength↑ Coordination↑ Physical capacity↑ Cardiorespiratory fitness↑ |

[28]: A, [31]: A, [42]: D, [60]: C, [61]: B, [62]: A, [63]: A, [64]: A, [65]: A |

|

Urinary problems |

Exercise-based, biofeedback-assisted behavioral intervention Pelvic floor muscle exercise |

Muscle strength↑ |

[29]: B, [30]: B, [66]: A |

1 To use massage techniques for pwPD with constipation problems. 2 “↑” represents increase; “↓” represents decrease. 3 Studies have shown that yoga can be considered as a therapy in treating depressive and anxiety disorders. Following along from the suggested exercise mode that targets the alleviation of the symptoms pwPD have, physical improvements then appear. 4 The level of evidence of each reference is graded as A: overwhelming data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs); B: quasi-experimental design; C: results stem from uncontrolled, nonrandomized, and/or observational studies; D: review or evidence insufficient for categories A to C.

Balance Training

Basal ganglia degeneration involves a number of physiological systems essential for balance control. Dysfunctional basal ganglia would deteriorate the central nervous system’s ability to translate sensory information, including somatosensory, vestibular, and visual, into a single reference frame, which is critical for assessing limb and body positioning with regard to the environment. Motor regulation deficient in PD arises from problems of adopting postural synergies, inadequate inter-segmental coordination, and delayed response in motor commands when working within different tasks. Specifically, it is essential to involve balance training to improve functions, or impairments, of balance control in relation to PD symptoms.

A weak ability to adapt to balance changes causes the increased risk of falling and the resulting injuries, e.g., hip fracture. It is evident that an integrative therapy for improving the response of pwPD is a necessity. Consequently, scholars and clinicians have developed and evaluated exercise interventions, particularly on balance.

Tai Chi, a Chinese martial arts discipline, has been proven as a useful exercise method for pwPD since it incorporates diverse techniques such as weight shifting, slow and controlled movement, trunk rotations, different stances, multidirectional stepping, and maintenance of postures that directly target PD balance and gait [20].

Dancing is another program that is considered effective for treating PD symptoms that are directly associated with dancing movements, including turning, backward walking, dynamic balance, and multitasking skills. On the other hand, the essence of dance includes social and enjoyable facets that could benefit the emotional and psychological aspects of pwPD and further build pwPD’s social network.

Balance impairments are the top concern of all motor impairments affecting pwPD. Balance is highly related to falls risk, thus exercises such as Tai Chi, dance, biking, and boxing, are supported by research showing the positive effects on pwPD due to their focus on training weight shift and postural control.

Exercise for Cognitive Dysfunction

There are laboratory studies articulating the effects of exercise on the brain health of pwPD. Effects include neuro-protection (slow, negate, or reverse the neuro-degenerative process) and neuro-restoration (adaption of compromised neural pathways).

Studies have shown that regular exercise both triggers and maintains the production of glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) producing cells in the substantial nigra where DA neurons are located, and then lead to an increase in dopamine release [67]. From a pharmacological treatment point of view, the finding is especially significant due to the reduction of relying on levodopa, going forwards for patients with early PD symptoms. In regard to the effectiveness of reducing PD symptoms such as tremor at rest, rigidity, and difficulty in exercising, levodopa is considered the most effective drug that, on the other hand, also causes unwanted effects such as dyskinesias. With the involvement of exercise intervention, these unwanted effects can potentially be minimized or postponed.

Cognitive dysfunction is a severe symptom that pwPD suffer. In clinical practice, cognitive training is usually carried out separately from mobility training. From a former review, this training is effective for people living with PD [25,26].

Recent investigations have demonstrated improvements in the freezing of gait (FOG) after cueing or mobility interventions. However, the setting is done under the integration of cognition and mobility (rather than separately); research to date has not investigated the integration of freezing-specific motor and cognitive therapies for PD people with FOG. Research investigating the effects of targeted cognitive and motor interventions on freezing of gait severity is needed. Targeting Parkinson’s disease motor symptoms, exercise modes and improvements are listed in Table 3, which strive to provide an initial point for evaluation of such targeted cognition–mobility training in pwPD who suffer from motor symptoms.

Table 3. Exercise modes and improvements for cognitive dysfunction.

|

Cognitive Domains |

Exercise Mode |

Improvement |

References: Grade 3 |

|

Attention |

Dual-task walking, agility course Shifting focus between tasks Walking Visual/auditory cue training Agility training |

Divided ability↑ 1 Switching and shifting task ability↑ Selective ability↑ Alerting attention↑ Sustained↑ |

[25]: D, [26]: A, [68]: B |

|

Executive function |

Go/no-go punch training Muay-Thai Stretch training Strength training Balance training Endurance training Stroop walking 2 Visual/auditory cue training Regular exercise and performance-based physical function training |

Execution↑ Inhibition↑ Updating ability↑ Muscle power↑ Balance ability↑ Muscle strength↑ Body coordination↑ Big muscle group resistance↑ |

[31]: D, [68]: B, [69]: A, [70]: D, [71]: D |

1 “↑” represents increase; “↓” represents decrease. 2 An innovative technique that requires dual-tasking for testing executive function and detecting cognitive impairment. 3 The level of evidence of each reference is graded as A: overwhelming data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs); B: quasi-experimental design; C: results stem from uncontrolled, nonrandomized, and/or observational studies; D: review or evidence insufficient for categories A to C.

A recent study showed that general exercise may be as effective as LSVT BIG therapy on pwPD symptoms [72]. LSVT is a speech treatment protocol which stands for Lee Silverman Voice Treatment, and LSVT BIG is considered an intensive, effective, one-on-one treatment created to help people with Parkinson's disease and other neurological conditions address walking, balance, and other activities of daily living through training people to increase the size (amplitude) of their movements from head to toe like buttoning or writing [73]. BIG siginifies the technique of increasing the size (amplitude) of pwPD’s movements in LSVT BIG therapy.

It is suggested that a combination of skilled and aerobic training is best to trigger and maintain multiple mechanisms of neurogenesis. Forced rate, in other words, beyond what the participant would self-select, is recommended as well. Regarding the early phases of motor development and maximizing motor learning, the prefrontal cortex is a critical part. Cognitive engagement is required through verbal, proprioceptive feedback, dual tasking, cueing, and motivation.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/ijerph17082894