Conjugated block copolymers (cBCPs) refer to block copolymers that contain one or more conjugated polymer segments. It can be a combination of several conjugated polymer segments with different properties, or it can be a combination of conjugated polymer segments and non-conjugated polymer segments. cBCPs not only maintain the advantages of high conductivity and mobility of conjugated polymers, but also demonstrate features of morphological versatility and tunability of block copolymers. cBCPs have a great potential application in organic solar cells, organic field effect transistors, organic light-emitting diodes and other fields.

- conjugated block copolymers,block copolymers

1. Introduction

Conjugated polymers (CPs) have alternating single and double bonds in the polymer backbone, making the polymer chain rigid and conductive. In 2000, the Noble Prize in Chemistry was awarded to MacDiarmid, Heeger, and Shirakawa in recognition of their discovery of highly conductive polyacetylene [1]. Despite relatively low charge mobility and conductivity compared to inorganic materials, conjugated polymers have extraordinary advantages of solution processability, low cost, light weight, structural versatility, and easy functionality. CP-based organic electronic materials experienced rapid development during the past twenty years and have found broad applications in the field of organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) [2,3,4,5], organic field-effect transistors (OFETs) [6,7,8], organic photovoltaics (OPVs) [9,10], and organic thermoelectrics (OTEs) [11,12], etc.

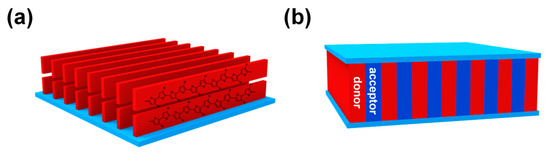

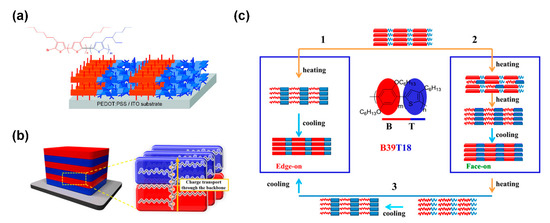

It has been widely accepted that the performance of CP-based devices is greatly influenced by the micro/nano morphologies in bulk or in thin films. For example, many CPs, e.g., poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT) [13], show better charge mobility when polymer chains pack in the “edge-on” orientation (Figure 1a). For OPV devices, the ideal morphology is the interpenetrated lamellar structure, which is beneficial to the charge separation and transportation of electrons and holes to different electrodes (Figure 1b) [14]. As a result, great efforts have been devoted to investigate the controlled formation of desired morphologies. Many factors, such as annealing condition, polymer solution concentration, selection of solvent, mole ratio of binary system, molecular weight, etc., can affect the morphologies of CPs in devices. Therefore, optimizing the morphologies of the active CP-containing layer is critical and one of the most time-consuming steps in device fabrication. In this context, conjugated block copolymers (cBCPs) have been proposed as an ideal solution to address this issue, since cBCPs might combine the advantages of high conductivity and mobility of CPs and morphological versatility and tunability of block copolymers (BCPs).

Figure 1. (a) The “edge-on” orientation of poly(3-hexylthiophene) (P3HT) that promotes charge transportation; (b) the proposed ideal interpenetrated lamellar structure of donor and acceptor materials in organic photovoltaics (OPV) devices.

BCPs are comprised of two or more polymeric blocks with different chemical compositions connected by covalent bonds. One of the most remarkable and fascinating features of BCPs is that they can self-assemble into different ordered micro/nano structures both in bulk and in solutions, which makes them good candidates for practical or potential applications at various areas, such as biomaterials, biomedicine, porous materials, nanolithography, organic electronics, etc. [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. The self-assembly of BCPs in bulk has been extensively studied since 1960s, and the experimental and theoretical knowledge is well established [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33].

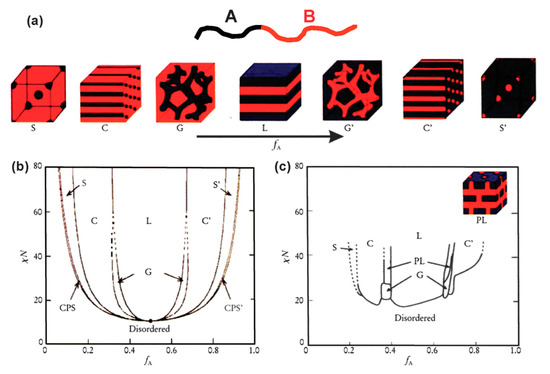

In the simplest case of diblock polymers, as shown in Figure 2a, due to the immiscibility of two different blocks, they can self-assemble into different ordered morphologies including spheres (S), cylinders (C), bicontinuous gyroids (G), lamellae (L), etc. The phase separation behaviors of BCPs depend on three parameters: (1) f, the volume fractions of the A and B blocks (fA and fB, with fA + fB = 1); (2) N, total degree of polymerization (NA + NB = N); (3) χ, the Flory–Huggins interaction parameter between two polymer blocks. The driving force of the phase separation is the Gibbs energy change in the self-assembly process, which can divide into mixing enthalpy and mixing entropy. Unlike binary mixture of small molecules or polymer solutions, the mixing entropy of BCPs is usually very small. Thus, the product of N and the χ parameter, which describes the degree of thermodynamic incompatibility between the two chemically different polymeric blocks, governs the phase separation behaviors in BCP self-assembly. Several theories have been developed to predict the phase separation behaviors of BCP in bulk [25,34]. Nowadays, the self-consistent mean-field (SCMF) theory can predict the phase diagram of BCPs in good agreement with experimental data, as shown in Figure 2b,c. For example, symmetric diblock copolymers (fA = fB = 0.5) self-assemble into lamellar morphology when the product χN value is larger than the order–disorder transition values ((χN)ODT = 10.5) [26]. In addition, many nonclassical spherical packing phases, e.g., Frank–Kasper phases, have also been predicted by SCMF [35] and later experimentally discovered in recent years [36].

Figure 2. (a) Equilibrium morphologies of AB diblock copolymers in bulk: S and S’ = body-centered cubic spheres, C and C’ = hexagonally packed cylinders, G and G’ = bicontinuous gyroids, and L = lamellae. (b) Theoretical phase diagram of AB diblocks predicted by the self-consistent mean-field theory, depending on volume fraction (f) of the blocks and the segregation parameter, χN; CPS and CPS’ = closely packed spheres. (c) Experimental phase diagram of polystyrene-b-polyisoprene copolymers, in which fA represents the volume fraction of polyisoprene, PL = perforated lamellae. (Reproduced with permission from [28], Copyright Royal Society of Chemistry).

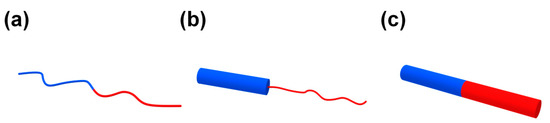

Compared to traditional BCPs, the study on cBCPs is still in the seminal stage, despite many recent progresses. A flexible polymer chain is usually considered as a Gaussian chain with a coil configuration, while the polymer chain of CPs is rigid and has a rod-like configuration. Distinguished from the conventional “coil–coil” type BCPs, cBCPs can be divided into two categories, namely, the “rod–coil” and “rod–rod” types (Figure 3). The rigid rod-like backbone of CPs leads to very different self-assembly behavior of cBCPs that are distinct from conventional “coil–coil” BCPs. For example, the (χN)ODT for symmetric “rod–coil” and “rod–rod” BCPs is 8.5 and 8.2, respectively, as predicted by R. Borsali et al. [37]. This result indicates that cBCPs containing a rigid block have stronger trend to phase separate than the “coil–coil” BCPs. In addition, conjugated polymer backbones have a strong tendency to form crystalline structures, and the melting temperature (Tm) of crystalline blocks may also affect the morphology and size of the phase separation. When the block segregation strength is very high ((χN)/(χN)ODT > 3), crystallization is restricted in the region of phase separation; when the block segregation strength is lower than the critical inter-block segregation strength ((χN)/(χN)ODT < 1.5), break-through crystallization occurs to induce the phase separation; when the segregation strength is in an intermediate range ((χN)/(χN)ODT = 1.5~3), the crystallization is not completely restricted to the area of phase separation [38]. However, the self-assembly of cBCPs is very complicated in a real situation due to the strong π–π interaction between conjugated polymer backbones.

Figure 3. (a) Conventional “coil–coil” block copolymers (BCPs); (b) “rod–coil” conjugated block copolymers (cBCPs); and (c) “rod–rod” cBCPs.

2. Synthesis of Conjugated Block Copolymers

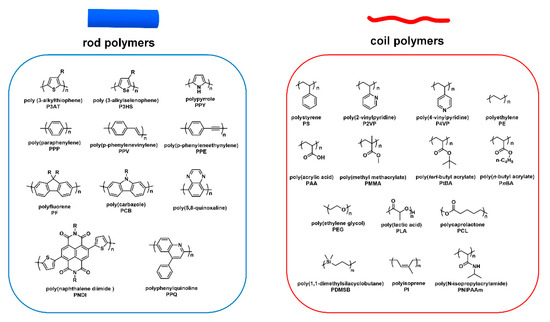

As mentioned above, cBCPs are divided into two categories, “rod–coil” (Figure 3b) and “rod–rod” (Figure 3c), based on the type of polymer blocks. “Rod–coil” cBCPs are composed of a rigid CP segment and a flexible polymer chain. Benefitting from the fast development of living polymerization techniques, the synthesis of “rod–coil” cBCPs are extensively studied, and people are able to synthesize various “rod–coil” cBCPs with different chemical components. Figure 4 shows representative chemical structures for rod and coil polymers. However, CPs are synthesized by metal catalyzed coupling reactions, which usually do not have the “living” feature. In this context, it is still very challenging to synthesize “rod–rod” cBCPs with well-controlled molecular weight and distribution. In this part, we will mainly focus on the synthesis of “rod–coil” and “rod–rod” cBCPs, and a few examples with different topological architecture will be also discussed.

Figure 4. Representative chemical structures for rod and coil polymers.

2.1. Synthesis of “Rod–Coil” Conjugated Block Copolymers

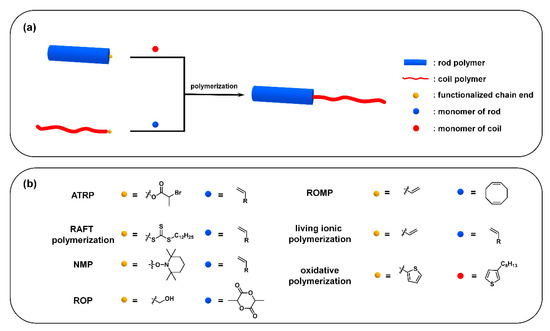

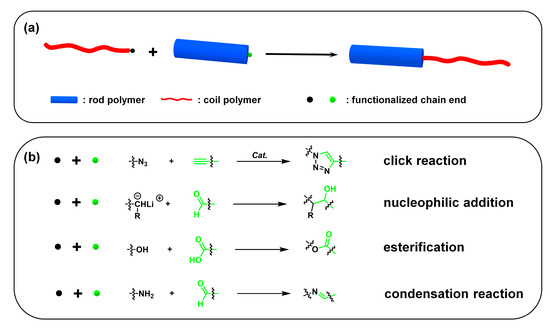

Usually, two strategies are employed to synthesize “rod–coil” cBCPs: (i) polymerization from macroinitiator (the grafting-from approach) (Figure 5a), and (ii) the coupling of a pre-synthesized rod and coil block (the grafting-onto approach) (Figure 6a). The rod CP blocks are generally prepared by a transition-metal catalyzed coupling reaction, such as Kumada, Suzuki, and Stille reaction. In order to endow sufficient solubility to CPs, soluble side chains are usually introduced to the backbone, which is critical to subsequent synthesis and processing steps. The coil blocks are normally synthesized from vinyl-based monomers via living/controlled polymerization, such as ionic polymerization, atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) [39], reversible addition−fragmentation chain-transfer (RAFT) polymerization [40], and nitroxide-mediated free radical polymerization (NMP) [41].

Figure 5. (a) The grafting-from approach from rod polymer and roil polymer; (b) representative functionalized chain end and monomer for different polymerizations.

Figure 6. (a) The grafting-onto approach; (b) representative functionalized chain ends and reaction types.

3. Self-Assembly of cBCPs

3.1. In Bulk

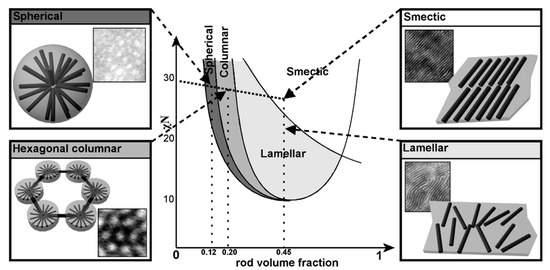

A lot of research has been published on the topic of “rod–coil” BCP self-assembly. “Rod–coil” BCPs show remarkably rich structural morphologies in bulk, such as lamellar phases, spherical, cylindrical, smectic, C-type smectic, O-type structure (HPL), hexagonal puck phases, hexagonally perforated layer structures, etc. [50,88,89,90,91]. Theoretical calculations also predict that A15 and gyroid phases could also exist in “rod–coil” BCPs. In the study of PPV-b-P4VP, Sary et al. found that they can form spherical, hexagonal columnar, lamellar, and smectic phases, based on volume fraction of PPV [92]. These results are consistent with theoretical predictions (Figure 8) [93]. However, for the conjugated “rod” blocks, they have a strong π–π interaction and are easy to crystallize and thus form fiber structures. The self-assembly of cBCPs is more complicated and different from “rod-coil” BCPs. The interaction between the anisotropic conjugated rods should be considered.

Figure 8. Comparison between the phase diagram predicted by Landau expansion theories for rod−coil block copolymers and the microphase-separated morphologies experimentally observed for PPV−P4VP block copolymers. (Reprinted with permission from Ref [92]. Copyright American Chemical Society).

For “rod–rod” cBCPs, only a few examples were reported. Due to the strong interaction “rod–rod” between blocks, i.e., π–π interaction and crystallization, it is difficult to prepare ordered nanostructures. The morphologies of “rod–rod” cBCPs are affected by the competition between rod–rod interaction and phase separation. The theory of “rod–rod” cBCP self-assembly is not yet clear, and their phase separation is generally independent of its specific chemical structure and composition. Noting that due to the high rigidity and poor curl ability of rod blocks, aggregates with curvature, e.g., spherical, are seldom formed in “rod–rod” cBCPs [94].

3.2. In Solution

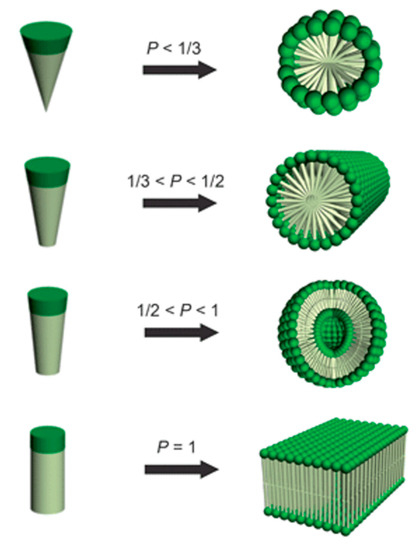

One key research area of cBCPs is their self-assembly behaviors in solution. Amphiphilic “rod–coil” cBCPs will self-assemble into various nanostructures depending on the molecular structures. Usually, amphiphiles with a hydrophobic chain and a hydrophilic head could self-assemble into spherical micelle, cylindrical micelle, vesicle, and lamellae (Figure 9), which can be predicted by the packing parameter, P = v/(a0lc), in which v is the volume of the hydrophobic chain, a0 is the polar head surface at the critical micelle concentration (cmc), and lc is the hydrophobic chain length [95]. Based on this theory, the aggregates of amphiphilic “rod–coil” cBCPs in solution could be tuned by changing the ratio of rod/coil. Kim et al. reported that a series of carbohydrate conjugate rod−coil amphiphiles with different rod/coil ratios are able to self-assemble into spheres, vesicles, and cylinders [96,97]. Selective solvent concentration is another parameter that affects the morphologies of amphiphilic “rod–coil” cBCPs in solution. For example, poly(phenylquinoline)-b-polystyrene(PPQ-b-PS) formed lamellar structures in dichloromethane/trifluoroacetic acid(DCM/TFA) (v/v = 1) mixed solvent and cylinders in DCM/TFA (v/v = 1/9) at room temperature. TFA is a good solvent for the conjugated PPQ block and protonates its imine nitrogen, while the coil PS block is insoluble in TFA [98]. Tung et al. reported that PF-b-PAA formed a tape-like structure when the coil part is short. When PAA block increased, various morphologies were observed with methanol concentration [42]. In addition to rod/coil ratios and selective solvent concentration, there are also other parameters that drive the self-assembly of “rod–coil” cBCPs in solution including pH values, temperature, the presence of additives and block compositions, etc. Several comprehensive reviews related to “rod–coil” cBCPs have been published [99,100,101,102,103,104].

Figure 9. Dependence of nanostructure morphologies on the relative volume fraction of hydrophobic and hydrophilic blocks. (Reprinted with permission from Ref [95]. Copyright Royal Society of Chemistry).

3.3. In Thin Film

Semiconducting CPs can be processed in organic solvents, and their electronic properties are largely determined by the nanostructure of the film. The orientation of polymer backbone is very important and has a remarkable effect on the charge mobility. Sirringhaus et al. found that mobility of edge-on orientated P3HT was two orders of magnitude of face-on orientated P3HT in 1999 [105]. Due to the anisotropy of transport properties, when semiconducting CPs self-assemble into edge-on lamellar morphology, charge transportation is more favorable compared to face-on orientation. Serials of “rod–coil” cBPCs were synthesized and their morphologies were investigated, including P3HT-b-PS, P3HT-b-PI, P3HT-b-PMMA, P3HT-b-PEG, etc. For example, Oh et al. designed a P3HT-b-PEG polymer in which PEG was amphiphilic and could cause self-assembly at a gas–liquid interface. P3HT-b-PEG thin films prepared on an inclined water surface have a long-range order and direction-controlled P3HT nanowire arrays, which have better hole mobility than P3HT-b-PEG thin films prepared on a flat water surface [57]. Han et al. found that P3DDT-b-PLA could self-assemble into lamellar morphology in thin film after solvo-microwave annealing, in which a P3DDT block has an edge-on orientation [106].

In “rod–coil” cBCPs, the coil block are generally insulating polymers and therefore will lower the carrier concentration, limiting their device performance. In this context, all conjugated “rod–rod” cBCPs have become a focus of interest. Several conjugated “rod–rod” cBCPs have been synthesized with excellent charge-transporting mobility, and their thin film morphologies were also investigated [61,62,63,107,108,109,110]. Zhang et al. synthesized a series of highly regioregular poly(3-hexylthiophene-b-3-(2-ethylhexyl)thiophene)s (P3HT-b-P3EHT) and found that the P3EHT block could induce the self-assembly of P3HT in thin film (Figure 10a) [62]. For poly(p-phenylene)-b-(3-hexylthiophene) (PPP-b-P3HT), Yang et al. discovered that edge-on and face-on orientation could be tuned by different annealing processes (Figure 10c) [111]. End-on orientation is also achieved by “rod–rod” cBCPs. Lee et al. prepared poly(3-dodecylthiophene)-b-poly(3-(2-(2-(2-methoxyethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)methyl thiophene) copolymer (P3DDT-b-P3TEGT). A P3DDT-b-P3TEGT thin film showed parallel oriented lamellar microdomains to the substrate in which the polymer backbones are perpendicular to the substrate and thus show improved hole mobility along the vertical direction compared with P3DDT (Figure 10b) [65].

Figure 10. (a) “Edge-on” orientation of poly(3-hexylthiophene-b-3-(2-ethylhexyl)thiophene)s (P3HT-b-P3EHT) in thin film; (Reprinted with permission from Ref [62]. Copyright American Chemical Society); (b) “end-on” orientation of poly(3-dodecylthiophene)-b-poly(3-(2-(2-(2-methoxyethoxy)ethoxy)ethoxy)methyl thiophene) copolymer (P3DDT-b-P3TEGT) in thin film; (Reprinted with permission from Ref [65]. Copyright American Chemical Society); (c) three different self-epitaxial crystallization circles by controlling the heating process for poly(p-phenylene)-b-(3-hexylthiophene) (PPP-b-P3HT). (Reprinted with permission from Ref [111]. Copyright American Chemical Society).

For binary donor–acceptor mixed bulk heterojunction (BHJ) solar cells, it is very challenging to fully control the nano-phase separation in order to achieve better exciton dissociation at the donor–acceptor interface. Using cBCP is considered to be an ideal solution to resolve this problem, even though great efforts have been made to tune the morphology of the active layer, including the choice of casting solvent, solvent evaporation rate, and thermal or solvent annealing. In 2000, Stalmach et al. reported a diblock copolymer composed of PPV and polystyrene functionalized with fullerenes(PSFu), in which PS blocks are partially functionalized with fullerene. In a spin-cast film of PPV-b-PSFu, a micrometer-scale, honeycomb-like nanostructure is obtained, and luminescence from PPV is quenched indicating efficient electron transfer to C60 [112]. Zhang et al. report that “rod–coil” donor–acceptor copolymer poly(thiophene-b-perylene diimide) copolymer P3HT-b-PDI formed fibrillar morphology in thin film after solvent vapor annealing and gave a power conversion efficiency of 0.49% in a solar cell device. A donor–acceptor type “rod–rod” block can self-assemble into a donor–acceptor alternating lamellar nanostructure, which is beneficial for exciton dissociation in organic solar cells. Guo et al. designed and prepared a novel donor–acceptor type poly(3-hexylthiophene)-b-poly((9,9-dioctylfluorene)-2,7-diyl-alt-[4,7-bis(thiophen-5-yl)-2,1,3-benzothiadiazole]-2′,2″-diyl) (P3HT-b-PFTBT) block copolymer. By using P3HT-b-PFTBT as an acting layer, 3% efficiency was achieved for OPV devices. X-ray scattering results demonstrated that the high device performance of P3HT-b-PFTBT was due to self-assembly into lamellar structures with primarily face-on crystallite orientations [14].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/polym13010110