A biosensor is an analytical device that is composed of a bioreceptor, a transducer, and a signal processor for detecting biological substances and monitoring biological interactions.

- optical biosensors

- point-of-care

- integration

1. Introduction

The transduction methods for biosensing applications are mainly based on optical, physical, chemical, electrochemical, or mechanical properties of the functional biorecognition materials (e.g., enzyme, antibody, aptamer, and DNAzyme) [1,2,3,4]. The sensitivity and selectivity are two critical parameters in the development and application of biosensors. Among various types of sensors, optical biosensors offer great advantages over conventional analytical techniques because they enable direct, real-time, and label-free detection of many biological and chemical substances. Their advantages include high specificity, sensitivity, small size, and cost-effectiveness. The non-invasive optical detections have developed, in the past decade, from fluorescent spectroscopy to grating, SPR (surface plasmon resonance), SERS (surface-enhanced Raman scattering), GMR (guided mode resonance), etc. Fundamental light emission or light–matter interaction, such as fluorescent light emission from target analyte, optical diffraction due to light device structure interactions, and optical resonance within an optical cavity or designated structure, is employed by these optical sensing methods.

With the advance of clinical diagnostics, modern biosensing gradually evolves from off-site laboratory tests to near the patient on-site diagnosis [5,6,7]. The testing modality, referred to as point-of-care testing (POCT), emphasizes on less skilled labor involvement, easy-to-use, rapid diagnosis, and compact size at an affordable price [5,6,7,8]. Currently, POCT is available for a series of analyses by shrinking the instruments for the laboratory testing in size. For example, POCT is found for pregnancy testing, cardiometabolic testing, glucose testing, infectious disease testing (such as HIV, respiratory infection, and sexually transmitted diseases) and numerous other applications [8,9,10,11,12,13]. The above devices for point-of-care (POC) and those in development rely on various technologies. Integrated biosensors have the advantages of combining different test functionalities, miniaturization by embedding different sensor components, and integration with semiconductor fabrication process. For example, the lab-on-a-chip combines several analyses that are usually carried out in the laboratory into a single chip [14,15]. It represents a significant contribution toward POCT. The integration can be extended to other devices with different detection principles. Optical sensors integrated with microfluidic channels, electrical charge sensing, and mechanical sensing are particularly promising for next-generation POCT [16,17,18,19,20,21,22].

2. Classification of Optical Biosensors—Overview of the Principle and Applications

2.1. Fluorescence-Based Biosensors

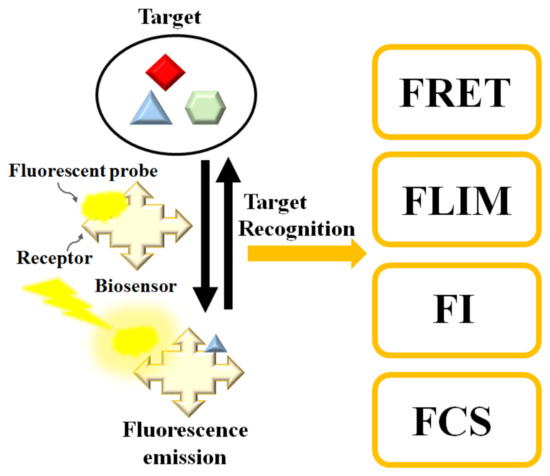

Fluorescence biosensors detect the concentration, location, and dynamics of biomolecules on the basis of the fluorescent phenomenon that occurs when electromagnetic radiation is absorbed by fluorophores or fluorescently labeled molecules so that the energy is converted into fluorescence emission (see Figure 1) [28,29,30]. A fluorescence biosensor includes the excitation light source (LEDs (light-emitting diodes), lasers), fluorophore molecules that label target biomolecules, and a photodetector that records the fluorescence intensity and spectrum. The fluorophore molecules can be small molecules, proteins, or quantum dots that are used to label proteins, nucleic acids, or lipids [31]. Generally, the excitation signal is biorecognized by the following techniques [32]: (1) FRET (Förster resonance energy transfer), (2) FLIM (fluorescence lifetime imaging), (3) FCS (fluorescence correlation spectroscopy), and (4) FI (changes in fluorescence intensity). In the next session, we review fluorescence-based biosensors integrated with microfluidic channels.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the fluorescence-based biosensor. Target analyte can be determined by FRET (Förster resonance energy transfer), FLIM (fluorescence lifetime imaging), FI (changes in fluorescence intensity), or FCS (fluorescence correlation spectroscopy).

2.2. Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering-Based Biosensors

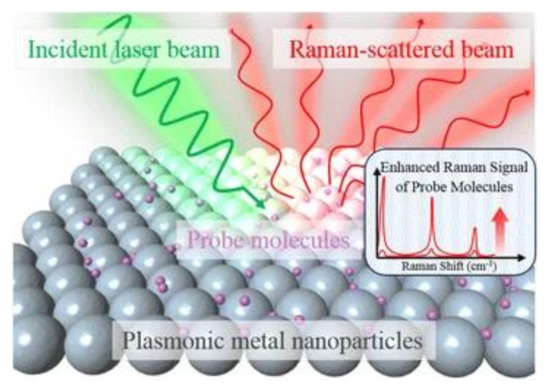

Raman scattering is an inelastic process when the kinetic energy of the incident photons is increased or decreased by interacting with molecular vibrations or rotations, phonons, or other excitations. The spectrum of the scattered photons indicates energy changes that are specific to the vibrational or rotational transitions modes of the molecular structure, which the biosensing of biomaterials is based upon. Because spontaneous (normal) Raman scattering is typically very weak, surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy or surface-enhanced Raman scattering employs surface-sensitive techniques to enhance Raman scattering by molecules adsorbed on a specific medium or interface to improve the sensitivity [33,34]. The enhancement factors for SERS, as compared to normal Raman scattering, are attributed to two mechanisms—an electromagnetic mechanism and a chemical mechanism [35,36,37,38]. The electromagnetic enhancement is generally considered as a major factor of SERS enhancement. The effect of wavelength shift is contributed from the excitation of localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) [39] (see Figure 2). It is regarded as the oscillation of conduction electrons in noble metal nanoparticles, sharp metal tips, or roughened metal surfaces. LSPR is a short-range detection in the vicinity of the metal surface (0–5 nm of the surface) [39,40]. The chemical mechanism depends not only on the substrate but also analyte molecules. It involves several different transitions/processes, which charge transfer between the energy levels of analyte molecules, with the fermi level of the substrate metal surface playing a critical role [41].

Figure 2. Schematic diagram of the SERS (surface-enhanced Raman scattering) process using metal nanoparticles to enhance the sensitivity [39]. Reproduced with permission from [39]. Copyright (2016) Springer Open.

Recently, the studies on SERS biosensing have gradually migrated from probing single location of the plasmonic structure to detecting many spots through bioimaging with SERS tag [42,43]. In order to improve the electromagnetic enhancement factor, researchers have demonstrated various fabrication methods, such as adjusting the morphology, dielectric property, and interparticle distance of the plasmonic nanostructures [44,45].

2.3. Photonic Crystal-Based Biosensors

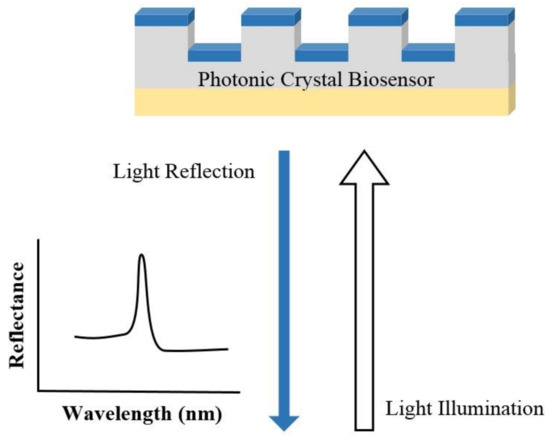

In PC structure, optical resonant modes or photonic bandgaps are created due to the periodic arrays of the refractive index. The periodic structure can be a Bragg reflector, one-dimensional (1D) slabs, or two-dimensional (2D) PC. An example of a PC biosensor is shown in Figure 3, where the resonant modes of the reflection spectrum are understood from the Bragg’s law of diffraction. Since the resonant wavelength is sensitive to the refractive index of the materials on the PC structure, PC can be used for biosensing [46,47]. The narrow (<1 nm) bandwidth and high (≈95–100%) reflectivity resonances enable PC biosensors for detecting small molecules, virus particles, DNA microarrays, and live cells [46,47,48,49,50,51,52].

Figure 3. Illustration of the sensing mechanism of a photonic crystal (PC) biosensor.

Recent advances in PC biosensors are focused on optimizing the instrumentation and device structures. For example, PC fluorescence enhancement was utilized for high-sensitivity multiplexed cancer biomarker detection [53]. Moreover, on the basis of the PC surface mode detection, researchers have developed label-free flow multiplex sensing of cancer biomarkers [54].

2.4. Guided Mode Resonance-Based Biosensor

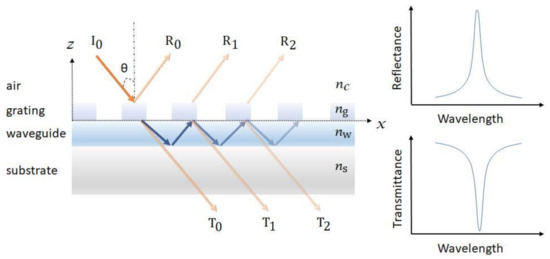

GMR is a resonance phenomenon occurred in the structure with an optical diffraction element and a waveguide layer. As shown in Figure 4, the guided modes are excited in the optical waveguide and are extracted to the air (reflectance R0, R1, R2… and transmittance T0, T1, T2.) by interacting with the diffraction structure, resulting in a very narrow reflectance or transmittance resonant bandwidth [55,56,57,58,59]. The resonant peak is highly sensitive to the changes in surrounding refractive index, which is used in determining target analytes and the corresponding concentrations [58].

Figure 4. Schematic of a guided mode resonance (GMR) sensor. The resonance can be observed from both the reflectance and transmittance spectra.

Recent advances in GMR sensor focus on the redesign of surface diffraction structure and improvement of sensitivity [60]. A “grating–waveguide” GMR sensor with coupled cross-stacked gratings was demonstrated to achieve a high wavelength and angular shift FOM (figure-of-merit) [61]. Moreover, an ultra-sensitive refractive index sensor employing phase detection in a GMR structure was also reported by incorporating the GMR structure in to a Mach–Zehnder interferometer. The researchers achieved a minimum phase shift of (1.94 × 10−3) π that corresponded to a refractive index change of 3.43 × 10−7 [58].

2.5. Plasmon-Based Biosensors

The coupling of light with continuous metallic films (SPR (surface plasmon resonance)) or metallic nanoparticles (LSPR) produces strong confinement of electromagnetic field intensity. The confined field enhances the interaction between light and target molecules, resulting in the increase of sensitivity.

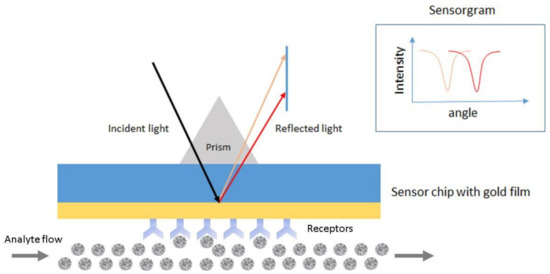

SPR is the resonant oscillation of conduction electrons at the interface between negative and positive permittivity material stimulated by incident light [62,63]. Figure 5 shows an example of a schematic configuration of an SPR biosensor. The incident light is totally internally reflected from the prism. The evanescent waves outside the prism interact with the plasma waves on the surface of the metal (typically Au or Ag) and induce plasmon resonance. SPR can be observed from the angle of minimum reflection (angle of maximum absorption), which is very sensitive to the refractive index of the biomaterial applied on the metal surface [63,64]. The method can be used to detect molecular adsorption, such as polymers, DNA, proteins, or molecular interactions [65,66,67].

Figure 5. Schematic configuration of an surface plasmon resonance (SPR) biosensor.

LSPR is the plasmonic effect that occurs when the conducting electrons within the nanoparticles are excited and oscillated with the incident light, a phenomenon that is mentioned in Section 2.2. LSPR-based biosensor monitors the changes of plasmon frequency with the local refractive index of the target analyte in the near field of nanoparticles. The nano-sized sensor has the advantage of portability and miniaturization, as compared to the planar-type SPR sensor.

Up until now, it has still been challenging for plasmon-based biosensors to detect small molecules or very low concentration of analytes. To improve LOD (limit-of-detection), recent effects on the development of SPR biosensing have focused on choosing proper receptors and calibration strategy, while for LSPR, a combination of fluorescent quantum dots with plasmonic metal nanoparticles has been exploited [68]. In addition, Ewa Gorodkiewicz et al. has an excellent review paper on recent publications on SPR biosensors between 2016 and 2018 [69]. Depending on the maturity of development, the authors categorized SPR biosensors into five stages ranging from simple marker detection to clinical application of the previously developed biosensors. Instrumental solutions and details of biosensor construction were analyzed by including chips, receptors, and linkers.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/bios10120209