Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) encompasses several cardiometabolic risk factors (obesity, insulin resistance, diabetes, and dyslipidemia), in addition to hepatic steatosis. Management strategies are primarily focused on controlling metabolic risk factors through lifestyle modifications, increased physical activity, and often the use of multiple medications (polypharmacy). Medications targeting metabolic risk factors include antidiabetics, insulin-sensitizing agents, lipid-lowering agents, antihypertensives, and antioxidants. The use of antidiabetics is supported by the fact that MASLD is regarded as an independent risk factor for, and frequently precedes the development of, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). We investigated whether the combination of empagliflozin/metformin improves MASLD disease outcomes in an experimental model of metabolic syndrome (MS). The empagliflozin/metformin combination therapy mitigates MASLD progression, likely by improving liver and mitochondrial function, and attenuating oxidative stress. Notably, co-therapy shows greater beneficial effects than single treatments. This protective effect appears to involve modulation of key transcription factors regulating lipid and carbohydrate metabolism, as well as influencing endogenous antioxidant defenses.

- Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated steatotic Liver Disease

- Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

- Lipid accumulation

- Oxidative stress

- Metformin

- Empagliflozin

1. Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), the most prevalent liver disease worldwide, is characterized by hepatic triglyceride accumulation (steatosis) greater than 5% in the absence of significant alcohol consumption [1]. Recently, it has been proposed to rename NAFLD to metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) [3,4]. In MASLD, in addition to hepatic steatosis, at least one of the five cardiometabolic risk factors of metabolic syndrome (MS) coexist, including systemic hypertension, dyslipidemia, obesity, a proinflammatory state, hyperglycemia, insulin resistance (IR), and diabetes [2][3]. The worldwide NAFLD/MASLD prevalence is estimated at 29.7 to 44% in adults with significant geographic variations according to specific world regions [4]. The high prevalence of NAFLD/MASLD has been directly related to a global increase in high-fat and hypercaloric diet intake, as well as a sedentary lifestyle, which in turn is closely linked to an imbalance between calorie consumption and energy expenditure. This imbalance generates excess energy stored as fat in white adipose tissue, leading to obesity, high fasting plasma glucose, and IR [5]. Obesity increases the availability of plasma lipids and the uptake of free fatty acids (FFAs) within hepatocytes, promoting hepatic lipid accumulation either through β-oxidation inhibition or FFAs esterification with glycerol to form triglycerides (steatosis) [5][6]. Additionally, increased FFAs levels trigger inflammation by facilitating oxidative stress, likely related to mitochondrial dysfunction and increased synthesis of inflammatory cytokines and fibrosis [7]. It has been described that de novo lipogenesis and inhibition of FFA oxidation are related to upregulation of the transcription factor sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c) [6][8]. Given the comorbidities associated with NAFLD/MASLD development and its worldwide prevalence, investment in prevention programs and the search for effective treatments are crucial. In this context, sustained weight loss of 5–10% and improvement in fasting glucose and insulin resistance are the most effective non-pharmacological treatments. The use of antidiabetics is supported by the fact that MASLD is regarded as an independent risk factor for, and frequently precedes the development of, type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Conversely, MASLD and diabetes often coexist in a high percentage of patients with diabetes [9]. Metformin, a first-line anti-diabetic drug, improves fatty acid oxidation, inhibits lipolysis in adipose tissue and lipogenesis in the liver, and reduces hepatic gluconeogenesis, but it has limited efficacy in improving the histological features of MASLD [10]. Empagliflozin, another class of anti-diabetic drugs belonging to the sodium–glucose cotransporter type 2 inhibitor class (SGLT2i), controls blood glucose independently of insulin secretion while increasing urinary glucose excretion [11]. Although metformin and SGLT2i alone have shown significant benefits in diabetes, obesity, and even in cardiovascular disease, a comparative analysis in co-therapy has not been performed. Therefore, this study aims to assess the effect of empagliflozin/metformin combination therapy on MASLD progression associated with MS by evaluating its impact on risk factor control, histopathological changes, and oxidative stress.

2. Results

The group that received the combination with empagliflozin/metformin showed a decrease in body weight and fasting blood glucose compared with the MASLD group. Moreover, the treatment with empagliflozin/metformin was effective in decreasing TG, total cholesterol, and restoring plasma HDL-c levels.

The combination therapy was effective in reducing the levels of liver markers (ALT, AST, ALP, GGT, TB, and DB), liver weight, and hypertrophy index, and particularly in the reduction of ALP and GGT, when compared with the monotherapy (Empa or Met) groups and the MASLD group.

2.1. The Combination Empa+Met Alleviates Liver Damage and Hepatic Lipid Accumulation in MASLD

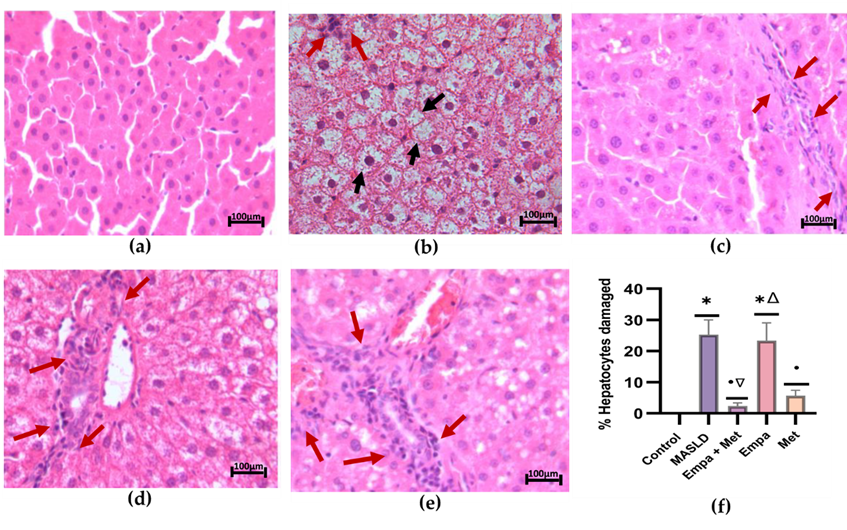

The micrograph of the MASLD group showed macrovesicular steatosis, with hepatocytes containing a single large vacuole that displaced the nucleus towards the cell periphery. The empty spaces in the hepatocytes were due to the presence of fat dissolved during fixation (Figure 1b). In the group treated with the empagliflozin/metformin combination (Figure 1c), a significant reduction in hepatocyte steatosis was observed, with a decrease or elimination of lipid droplets and cytoplasmic vacuolization. Although a decrease in the percentage of damaged hepatocytes was observed with the different treatments, the Empa+Met combination showed a significant reduction in liver damage compared with the MASLD group (Figure 1f).

Figure 1. Histopathological analysis. (a) control; (b) MASLD; (c) Empa+Met; (d) Empa; (e) Met; (f) % Hepatocytes damaged. Black arrows indicate hepatocyte damage, and red arrows indicate inflammatory infiltrate. Empagliflozin (Empa), metformin (Met), empagliflozin + metformin (Empa+Met), metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). All sections were hematoxylin/eosin-stained, 200× magnification. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 3, analyzed by one-way ANOVA. Statistical significance was established as * p< 0.05 vs. control; • p < 0.05 vs. MASLD, ▽ p < 0.05 vs. Empa; Δ p < 0.05 vs. Met.

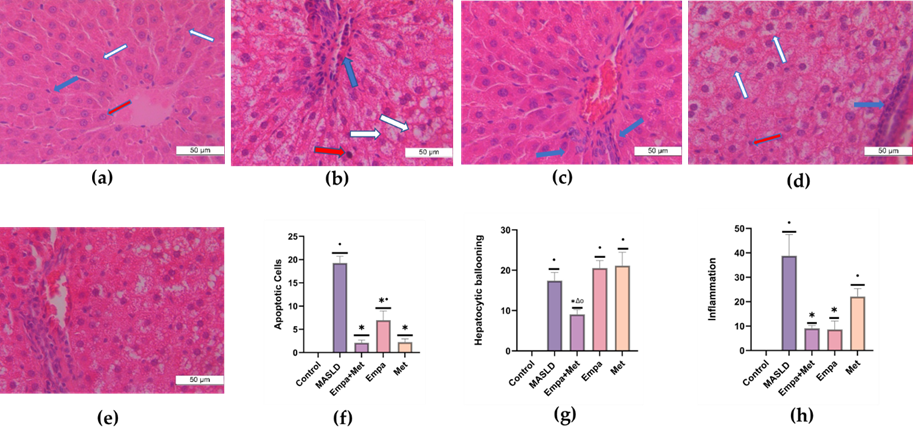

In addition, the MASLD group showed an increased presence of hepatic apoptosis, characterized by hepatocytes with condensed nuclei showing a darker coloration (red arrow). Moreover, markedly larger hepatocytes with lighter and less dense cytoplasm (hepatocyte ballooning) (white arrow) and the exacerbated presence of mixed inflammatory cells in the hepatic lobule (blue arrow) were observed (Figure 2b). The Empa+Met combination was the most effective therapy, with the most significant reduction in the number of apoptotic cells/field, fewer ballooning hepatocytes, and less lobular inflammation (Figure 2f, g, and h).

The degree of NASH activity and presence of fibrosis in the MASLD model were determined according to the score reported by Brunt E.M. and Tiniakos D.G., 2010 [12]. Control Group: No NASH; MAFLD Group: Severe NASH; Empa+Met Group: Moderate NASH; Empa Group: Moderate NASH; Met Group: Moderate NASH.

Figure 2. Analysis of NASH activity. (a) control; (b) MASLD; (c) Empa+Met; (d) Empa; (e) and Met; (f). Quantitative analysis of apoptotic cells (g), hepatocytic ballooning (h), and inflammation (h). Red arrows indicate hepatic apoptosis, blue arrows indicate the presence of inflammatory cell infiltrate, and white arrows indicate balloonised hepatocytes. Empagliflozin (Empa), metformin (Met), empagliflozin + metformin (Empa+Met), metabolic-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). All sections were hematoxylin/eosin-stained, 400× magnification. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 3, analyzed by one-way ANOVA. Statistical significance was established as * p < 0.05 vs. control; • p < 0.05 vs. MASLD, ▽ p < 0.05 vs. Empa; Δ p < 0.05 vs. Met.

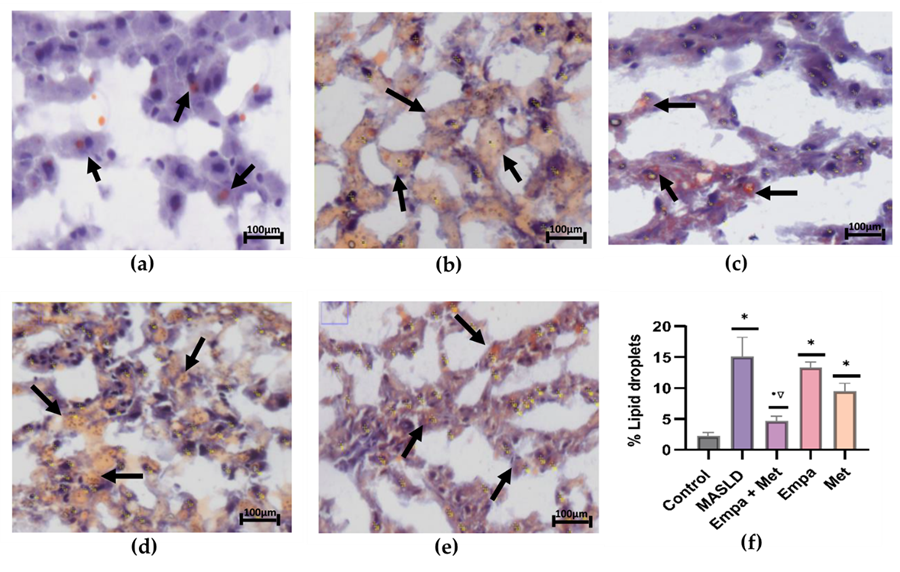

Figure 3a depicts the stain of a representative sample from the control group, where a few faint orange-positive stains indicate minimal lipid deposition. As can be observed in the MASLD group, a higher intensity of orange-positive stains indicates greater lipid deposition than in the control group (Figure 3b). The combination treatment reduced the positive staining, demonstrating a decrease in lipid accumulation (Figure 3c). The single-agent treatments also reduced lipid accumulation but were not as effective as the combination (Figure 3f).

Figure 3. Analysis of the lipid accumulation in the liver: (a) control; (b) MASLD; (c) Empa+Met; (d) Empa; (e) Met; (f) quantitative analysis of lipid droplets. Empagliflozin (Empa), metformin (Met), empagliflozin + metformin (Empa+Met), metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). Black arrows indicate lipid droplets. All sections oil red staining, 50× magnification. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 3, analyzed by one-way ANOVA. Statistical significance was established as * p < 0.05 vs. control; • p < 0.05 vs. MASLD, ▽ p < 0.05 vs. Empa; Δ p < 0.05 vs. Met.

2.2. Effect of the Empagliflozin/Metformin Combination on Oxidative Stress in Liver Tissue

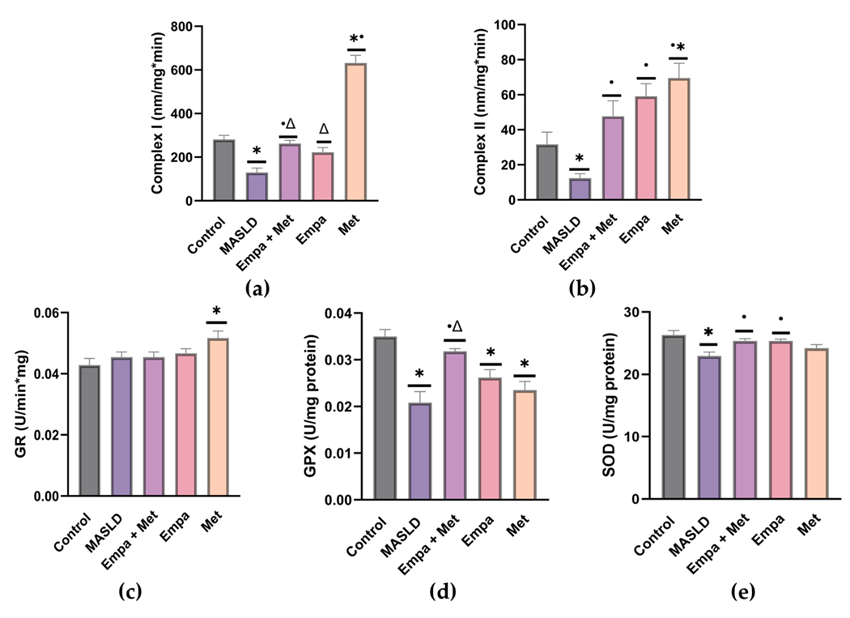

The MASLD group showed a significant decrease (p < 0.05) in the activity of both mitochondrial complexes (I and II) compared with the control group (Figure 4). Compared with the MASLD group, we observed improved activity of both mitochondrial complexes in the co-therapy group as well as in the single-therapy groups (Figure 4).

Furthermore, the activities of GPX and SOD were impaired in the livers of the MASLD group (Figure 4b and c). We observed that all the treatments, especially the Empa+Met combination, improved GPX and SOD activity (Figure 4b and c), indicating that co-therapy helped restore levels of these antioxidant enzymes compared with the MASLD group (Figure 4b and c).

Figure 4. Evaluation of oxidative stress. Mitochondrial complexes activities: (a) Complex I; (b) Complex II; and activities of (c) Glutathione reductase; (d) Glutathione peroxidase, and (e) superoxide dismutase. Empagliflozin (Empa), metformin (Met), empagliflozin + metformin (Empa+Met), metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, n = 6, analyzed by one-way ANOVA. Statistical significance was established as * p < 0.05 vs. control; • p < 0.05 vs. MASLD, ▽ p < 0.05 vs. Empa; Δ p < 0.05 vs. Met.

2.3. Expression of Transcription Factors Involved in Lipid Metabolism and Oxidative Stress in the Liver

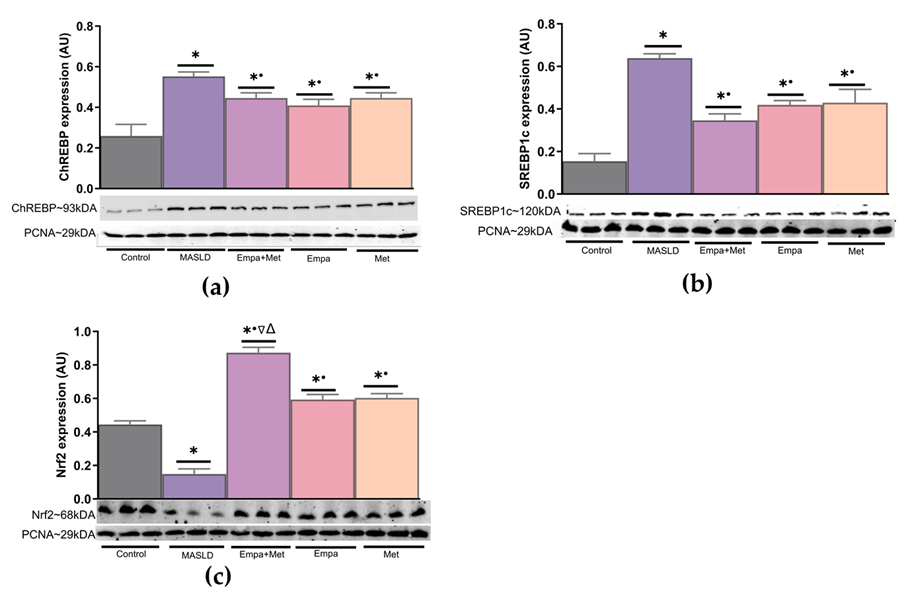

To explore the cellular mechanisms involved in the benefits observed, the nuclear translocation of sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP), carbohydrate-responsive element-binding protein (ChREBP), and nuclear factor-erythroid 2 p45-related factor 2 (Nrf2) was assessed in nuclear extracts of liver homogenates.

The nuclear translocation of lipogenesis-related transcription factors ChREBP and SREBP1c was increased in the livers of the MASLD group compared with the control group (Figure 5a and b); in contrast, the expression of Nrf2 was decreased (Figure 5c). The empagliflozin/metformin combination restored changes in transcription factor expression compared with the MASLD group.

Figure 5. Expression of transcription factors associated with the modulation in the expression of proteins involved in lipid and carbohydrate metabolism and the endogenous antioxidant system in the liver. (a) ChREBP expression; (b) SREBP1c expression, and (c) Nrf2 expression. Empagliflozin (Empa), metformin (Met), empagliflozin + metformin (Empa+Met), metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). For representative Western blotting, 3 randomly selected samples per group were analyzed, respectively. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM, analyzed by one-way ANOVA. Statistical significance was established as * p< 0.05 vs. control; • p < 0.05 vs. MASLD, ▽ p < 0.05 vs. Empa; Δ p < 0.05 vs. Met.

3. Conclusion

This combination could be considered a promising therapeutic option for the treatment or prevention of MASLD related to metabolic syndrome by improving liver and mitochondrial function and mitigating oxidative stress through the enhancement of endogenous antioxidant systems, although further studies—including human trials—are needed to explore optimal dosages, safety, mechanisms of action, and long-term effects.

This entry is adapted from: 10.3390/ijms26189010

References

- Hager H. Shaaban, I.A., Ahmed El-Mallah, Rania G. Aly, and A.W. Ahmed F. El-Yazbi, Metformin, pioglitazone, dapagliflozin and their combinations ameliorate manifestations associated with NAFLD in rats via anti-inflammatory, anti-fibrotic, anti-oxidant and anti-apoptotic mechanisms. Life Sciences 2022. 308: p. 120956.

- Mohammad Shafi Kuchay, S.K., Sunil Kumar Mishra, Khalid Jamal Farooqui, Manish Kumar Singh, Jasjeet Singh Wasir, Beena Bansal, Parjeet Kaur, Ganesh Jevalikar, Harmendeep Kaur Gill, Narendra Singh Choudhary, Ambrish Mithal, Effect of Empagliflozin on Liver Fat in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Randomized Controlled Trial (E-LIFT Trial). Diabetes care, 2018. 41(8): p. 1801–1808.

- Katsiki, N., Mikhailidis, D. P., & Mantzoros, C. S., Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and dyslipidemia: An update. Metabolism: clinical and experimental, 2016. 65(8): p. 1109–1123.

- Younossi, Z.M., M. Kalligeros, and L. Henry, Epidemiology of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol, 2025. 31(Suppl): p. S32-s50.

- Remus Popa, A., et al., Risk factors for adiposity in the urban population and influence on the prevalence of overweight and obesity. Exp Ther Med, 2020. 20(1): p. 129-133.

- Yin, X., et al., Advances in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Int J Mol Sci, 2023. 24(3).

- Radosavljevic, T., et al., Altered Mitochondrial Function in MASLD: Key Features and Promising Therapeutic Approaches. Antioxidants (Basel), 2024. 13(8).

- Zhu, Z., et al., In-depth analysis of de novo lipogenesis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Mechanism and pharmacological interventions. Liver Research, 2023. 7(4): p. 285-295.

- Ntikoudi, A., et al., Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) and Type 2 Diabetes: Mechanisms, Diagnostic Approaches, and Therapeutic Interventions. Diabetology, 2025. 6(4): p. 23.

- Gkiourtzis, N., et al., The benefit of metformin in the treatment of pediatric non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Pediatr, 2023. 182(11): p. 4795-4806.

- Bica, I.C., Stoica, R. A., Salmen, T., Janež, A., Volčanšek, Š., Popovic, D., Muzurovic, E., Rizzo, M., & Stoian, A. P., The Effects of Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter 2-Inhibitors on Steatosis and Fibrosis in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease or Steatohepatitis and Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania), 2023. 59(6): p. 1136.

- Brunt, E.M. and D.G. Tiniakos, Histopathology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol, 2010. 16(42): p. 5286-96.