Artificial intelligence (AI) is rapidly transforming healthcare around the world with its greatest potential in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), which face workforce shortages, long travel distances, and limited diagnostic capability. AI is an equalizing agent in resource-limited environments, reinforcing the obligation for safe and responsible use for both patients and healthcare workers as highlighted in this perspective. For instance, patients from rural areas can use AI-enabled medication checkers, to identify possible drug interactions, explain side effects, and provide reliable information about known illnesses—with strong disclaimers against self-diagnosis or self-medication. For healthcare workers, AI can create efficiency in workflow, assist in the review of radiologic findings, and support task-shifting in overburdened health systems. This perspective also emphasizes the importance of AI literacy, ethical guidelines, and free continuing professional education (CME) offered by governments and policymakers to support equitable and context appropriate use. Thus, AI can provide a useful, responsible, demonstrably helpful force multiplier, augmenting healthcare capacity, patient safety, and access to quality care in low- and middle-income countries while giving providers helpful advantages in systems where they face overwhelming constraints of time and expertise.

- Artificial intelligence

- resource-limited settings

- healthcare delivery

- digital triage

- health equity

Deeply impacting global health systems, artificial intelligence (AI) is enhancing capabilities in diagnostic decision-making, triage, and the creation of workflows.[1] High-income countries have demonstrated AI's promise in expediting radiologic interpretation and predictive modeling, however, the need and potential for impact may be even greater in low- and middle-income countries.[2] Chronic health workforce shortages, geographic isolation, and fragile infrastructure significantly inhibit the potential ability to access quality healthcare. As next-generation health professionals in a developing country, we want AI innovations to be seen as less of a luxury, but more a great equalizer that can leverage limited resources to improve and extend care to those individuals who would benefit the most. [2][6] Artificial intelligence also provides us with opportunities to collect and analyze epidemiological data in rural communities where we often lack health surveillance systems. Aggregating anonymized patient data across these communities will allow for the identification of patterns that inform outbreaks of disease, vaccine uptake, and chronic disease burden. This information can be useful to policymakers to enhance population health response from a proactive to reactive approach. In settings where public health infrastructure is lacking, collecting data via AI can be a powerful mechanism for improving population health. [6]

Source: Htet Lin Aung & Kaung Wai Yan Lwin

For the millions of rural patients who live far away from hospitals or clinics, AI can function as a first step of guidance (not diagnosis or treatment decisions) from a safe, supportive standpoint for educational purposes.[7] One of the significant issues facing rural hospitals is medication errors, particularly among patients without a strong understanding of their prescriptions. The AI tools can cross-check prescribed medications for interaction, dosage error, and contraindications.[3] They can produce patient-friendly explanations, in either audio or visual format, of when and how much to take their medicines in local languages (although AI translations are not fully supported in some languages). Additionally, the AI can highlight any potential side effects. These use cases may increase patient safety and health literacy leading to clinical visit. However, again, AI must still have associated expectations; patients should not consider AI as a resource for diagnosing or changing medications without discussing with healthcare professionals. [7][9]

In many LMIC environments, healthcare workers are tasked with an overwhelming patient volume and limited diagnostics. In this context, AI can be leveraged to greatly assist by summarizing patient data, identifying abnormal patterns in data, alleviating documentation burden, and improving communication through translation and speech.[5] AI can also serve as a secondary review for radiological findings, especially in areas lacking trained radiologists.[1] AI is not intended to replace clinicians but to serve as a force multiplier that enhances accuracy and efficiency whilst maintaining clinical oversight.[6] Numerous rural hospitals do not have specialists like radiologists, cardiologists, or infectious disease specialists. AI can act as a virtual "second opinion" for inpatients and outpatients. For example, AI-enabled image analysis can identify abnormalities in X-rays, CT scans, or ultrasounds, immediately alerting clinicians to the need for urgent intervention.[1][6] So, general practitioners or nurses can respond quickly instead of waiting for potentially delayed representation by telemedicine to process remote specialists' opinions. Hybrid approaches can give less-efficient, limited AI methods the oversight of clinical staff to safely expedite care in low-resourced settings.[2][8]

Despite its promise, AI poses risks as it is applied without adequate awareness of environmental context. Algorithms that rely predominantly on high-income country-specific data may have decreased validity or biased outputs in low and middle-income (LMIC) contexts.[6] Most healthcare workers also have little to no formal training in AI literacy, including understanding how model outputs are derived and where biases may be involved.[7] To address these shortcomings, policymakers will need to develop low-cost/ no-cost continuing medical education options focused on AI, and create ethical, transparent governance that protect patients and data.[8][9] Without these structures and failures of regulation or misuse of AI could contribute to diminished clinical autonomy or exacerbating inequities.

Educational harnessing the power of AI can target individual knowledge gaps and provide individualized modules, simulations, and case-based learning that reflects the disease burden locally.[8] In areas of rural practice where specialty training has limited access, follow-up care is often inconsistent for patients who struggle with limited literacy skills, resulting in hospital re admissions or worsening of chronic diseases. AI-enabled SMS or voice-call reminders can promote adherence to treatment, appointments, or vaccination programs.[8] Automated guidance could initiate and make outpatient follow-up more likely, as could AI guidance for caregivers with simple and straightforward instructions to use for home-based care. This ensures continuity of care despite patients' ability to read complex medical instructions or distance from health facilities.[2][5]

When utilized properly, AI enhances the patients–clinicians encounter. Patients with access to AI prior to the encounter are more likely to present their history in a more structured format, which enables more timely and accurate clinical assessments.[5] In addition, AI supported translation, transcription, and culturally adapted communication interfaces can help break down language barriers, build greater mutual understanding and create trust.[8] Instead of disrupting human connection, AI allows clinicians to focus on empathy, context, and shared decision-making.[9] Training local staff to manage AI tools, interpret outputs, and maintain devices is crucial for sustainability. Importantly, AI should augment human care rather than replace it, especially in communities where trust in healthcare providers is central to patient engagement.[1][9]

Table 1: AI Applications in Healthcare for Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs)

|

AI Application |

Target Users |

Key Benefits |

Ethical/Practical Considerations |

|

Medication Checkers & Symptom Guides |

Patients (especially rural) |

Identify potential drug interactions. Explain side effects. Provide credible disease information. |

|

|

Workflow Optimization Tools |

Healthcare workers |

Summarize patient data Reduce documentation burden. Assist triage and communication. |

|

|

Radiology Assistance |

Healthcare workers / Radiologists |

Secondary review of imaging. Detect abnormalities in absence of specialists. |

|

|

AI-driven Education & CME |

Healthcare workers |

Individualized learning modules. Virtual mentorship linking specialists. |

|

|

Language & Communication Tools |

Patients & Healthcare workers |

Translation and transcription. Culturally adapted communication. |

|

|

Predictive Triage Systems |

Patients & Health systems |

Prioritize care for high-risk cases. Optimize resource allocation. |

Table 2: AI Applications by Risk Level

|

User |

AI Application |

Risk Level |

|

Patient |

Education |

Medium |

|

Healthcare Worker |

Education |

Low |

|

Patient |

Clinical Support |

High |

|

Healthcare Worker |

Clinical Support |

High |

|

Patient |

Workflow |

Medium |

|

Healthcare Worker |

Workflow |

Medium |

|

Patient |

Communication |

Medium |

|

Healthcare Worker |

Communication |

Medium |

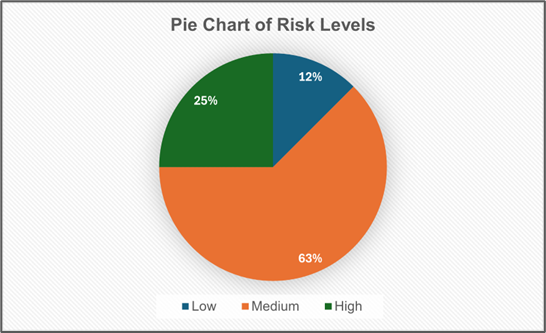

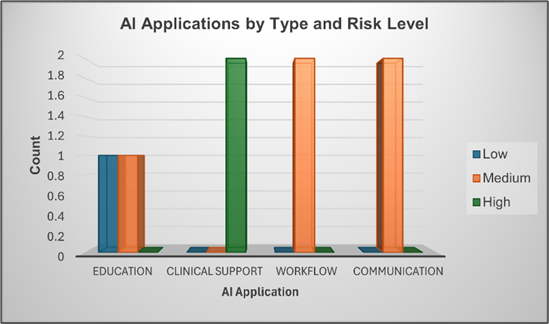

Table 2 summarizes the number of AI applications at each risk level for each type of AI application (Education, Clinical Support, Workflow, Communication).

Figure 1. The pie chart shows the distribution of AI applications across risk levels (Low, Medium, High). Each slice represents the proportion of applications at a given risk level.

Figure 2. The bar chart represents the number of AI applications per application type, broken down by risk level. Each bar shows the total number of applications for that category, with colored segments representing Low (Blue), Medium (Orange), and High (Green) risk.

In conclusions, the future of healthcare in lower- and middle-income countries depends on the early utilization of technologies that make use of AI, as well as on the management of ethical design, implementation, training and governance.[9] AI can be beneficial to patients in rural areas, can enhance clinical workflows, and can also increase educational opportunities for the health worker; however, AI must be a shared responsibility among clinicians, educators, technologists, and policymakers if it is to be ethically integrated.[2] Where AI is ethically governed in the context of local data and inclusive design, AI becomes a tool for empowerment—by facilitating healthcare equity and by servicing the vital human-centered focus of healthcare practice.[1][2][6]

This entry is adapted from: https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.13459.95523

References

- Junaid Bajwa; Usman Munir; Aditya Nori; Bryan Williams; Artificial intelligence in healthcare: transforming the practice of medicine. Futur. Heal. J. 2021, 8, e188-e194, .

- Tadeusz Ciecierski-Holmes; Ritvij Singh; Miriam Axt; Stephan Brenner; Sandra Barteit; Artificial intelligence for strengthening healthcare systems in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic scoping review. npj Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 1-13, .

- Elin Siira; Hanna Johansson; Jens Nygren; Mapping and Summarizing the Research on AI Systems for Automating Medical History Taking and Triage: Scoping Review. J. Med Internet Res. 2025, 27, e53741, .

- Azadeh Tahernejad; Ali Sahebi; Ali Salehi Sahl Abadi; Mehdi Safari; Application of artificial intelligence in triage in emergencies and disasters: a systematic review. BMC Public Heal. 2024, 24, 1-18, .

- Vito Santamato; Caterina Tricase; Nicola Faccilongo; Massimo Iacoviello; Agostino Marengo; Exploring the Impact of Artificial Intelligence on Healthcare Management: A Combined Systematic Review and Machine-Learning Approach. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10144, .

- Rune Chi Zhao; Xiuyuan Yuan. AI in Healthcare for Resource Limited Settings: An Exploration and Ethical Evaluation; Association for Computing Machinery (ACM): New York, NY, United States, 2025; pp. 1953-1960.

- Margaret Chustecki; Benefits and Risks of AI in Health Care: Narrative Review. Interact. J. Med Res. 2024, 13, e53616, .

- Raja-Elie E. Abdulnour; Brian Gin; Christy K. Boscardin; Educational Strategies for Clinical Supervision of Artificial Intelligence Use. New Engl. J. Med. 2025, 393, 786-797, .

- Ethics and governance of artificial intelligence for health: Guidance on large multi-modal models. World Health Organization. Retrieved 2025-11-22