The Portuguese Atlantic continental coast serves as a biogeographic transition zone where numerous macroalgal species reach their distribution limits, making it an especially intriguing area for studying shifts in species distribution. This region features sandy beaches and rocky outcrops that serve as habitats for a diverse range of organisms, including macroalgae. This illustrated guide aims to provide a simple and accessible overview of some of the most representative macroalgae species found along this coastline, specifically those designed for non-specialists in seaweed identification. Rather than offering a detailed identification key, the guide introduces key aspects of macroalgae—such as pigment composition, taxonomic classification, morphology, branching types, habitat on rocky shores, and potential human uses—in a clear and approachable format. Each species is accompanied by a photographic image, a general morphological description, and information about its typical habitat. Additionally, icons indicate whether a species has potential human applications or is considered non-indigenous. Species are categorized into green, brown, or red macroalgae based on their color and morphological characteristics.

- Rhodophyta

- Chlorophyta

- Heterokontophyta

- biodiversity

- ecology

- uses

Overview of Macroalgal Diversity and Taxonomy

Pigmentary Composition and Classification of Macroalgae

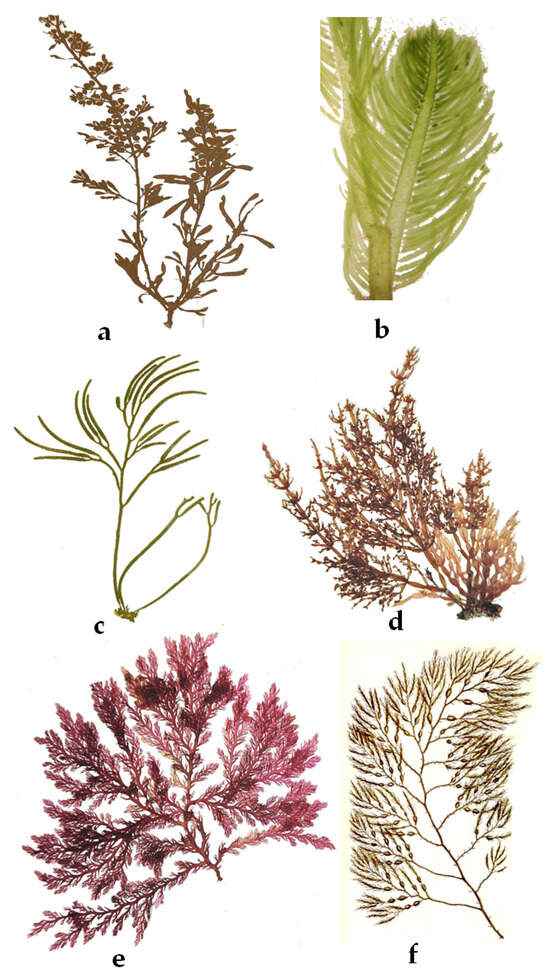

Morphological Types

Branching Types

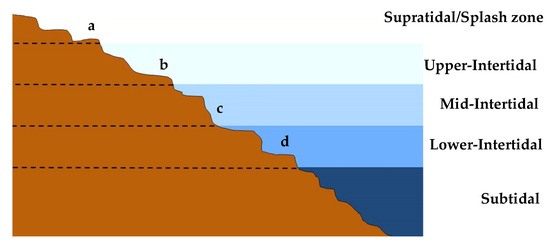

The Habitat of Rocky Shores

Non-Indigenous Algae on the Western Portuguese Coast

Uses

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/encyclopedia5040176

References

- Araújo, R.; Sousa-Pinto, I.; Bárbara, I.; Quintino, V. Macroalgal communities of intertidal rock pools in the northwest coast of Portugal. Acta Oecologica 2006, 30, 192–202.

- Verbruggen, H. Morphological complexity, plasticity, and species diagnosability in the application of old species names in DNA-based taxonomies. J. Phycol. 2014, 50, 26–31.

- Vasconcelos, R.P.; Reis-Santos, P.; Fonseca, V.; Maia, A.; Ruano, M.; França, S.; Vinagre, C.; Costa, M.J.; Cabral, H. Assessing anthropogenic pressures on estuarine fish nurseries along the Portuguese coast: A multi-metric index and conceptual approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2007, 374, 199–215.

- Gaspar, R.; Pereira, L.; Neto, J.M. Ecological reference conditions and quality states of marine macroalgae sensu Water Framework Directive: An example from the intertidal rocky shores of the Portuguese coastal waters. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 19, 24–38.

- Stewart, H.L.; Carpenter, R.C. The Effects of Morphology and Water Flow on Photosynthesis of Marine Macroalgae. Ecology 2003, 84, 2999–3012.

- Carpenter, R.C. Competition Among Marine Macroalgae: A Physiological Perspective. J. Phycol. 1990, 26, 6–12.

- Jurkus, E.; Povilanskas, R.; Taminskas, J. Current Trends and Issues in Research on Biodiversity Conservation and Tourism Sustainability. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3342.

- Bellgrove, A.; McKenzie, P.F.; Cameron, H.; Pocklington, J.B. Restoring rocky intertidal communities: Lessons from a benthic macroalgal ecosystem engineer. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 117, 17–27.

- Gaspar, R.; Fonseca, R.; Pereira, L. Illustrated Guide to the Macroalgae of Buarcos Bay, Figueira da Foz, Portugal; University of Coimbra: Coimbra, Portugal, 2020; 130p.

- Pereira, L. Guia Ilustrado das Macroalgas—Conhecer e Reconhecer Algumas Espécies da Flora Portuguesa; Coimbra University Press: Coimbra, Portugal, 2009; 90p.

- Bhuyan, M.; Islam, T.; Nabi, M.; Kunda, M. Pictorial Dictionary of Seaweed. 2023. Bangladesh Oceanographic Research Institute, 184p. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/378076262_Pictorial_Dictionary_of_Seaweed (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Pereira, L. Guia Ilustrado das Macroalgas Marinhas das Praias Rochosas da Figueira da Foz, Portugal/Illustrated Guide to the Marine Macroalgae of the Rocky Shores of Figueira da Foz, Portugal, 1ª Edição/Edition ed; CFE—Centre for Functional Ecology: Science for People & Planet—Marine Resources, Conservation and Technology—Marine Algae Lab: Coimbra, Portugal, 2025; in press.

- Pereira, L. Non-indigenous seaweeds in the Iberian Peninsula, Macaronesia Islands (Madeira, Azores, Canary Islands) and Balearic Islands: Biodiversity, ecological impact, invasion dynamics, and potential industrial applications. Algal Res. 2024, 78, 103407.

- Macreadie, P.I.; Jarvis, J.; Trevathan-Tackett, S.M.; Bellgrove, A. Seagrasses and Macroalgae: Importance, Vulnerability and Impacts. In Climate Change Impacts on Fisheries and Aquaculture; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 729–770.

- Yoon, H.S.; Andersen, R.A.; Boo, S.M.; Bhattacharya, D. Stramenopiles. In Encyclopedia of Microbiology, 3rd ed.; Schaechter, M., Ed.; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 721–731.

- Yoon, H.S.; Zuccarello, G.C.; Bhattacharya, D. Evolutionary History and Taxonomy of Red Algae. In Red Algae in the Genomic Age; Seckbach, J., Chapman, D.J., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 25–42.

- Pereira, L. Portuguese Seaweeds Website. Available online: http://www.flordeutopia.pt/macoi/ (accessed on 16 August 2025).

- Harvey, W.H. Phycologia Britânica; Several Volumes; Reeve & Benham: London, UK, 1851.

- Pereira, L. Edible Seaweeds of the World, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016; 442p, ISBN 9-781498-73047.

- Pereira, L. Therapeutic and Nutritional Uses of Algae. CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; 560p, ISBN 9781498755382.

- Leandro, A.; Pereira, L.; Gonçalves, A.M.M. Diverse Applications of Marine Macroalgae. Mar. Drugs 2020, 18, 17.

- Prisa, D.; Fresco, R.; Jamal, A.; Saeed, M.F.; Spagnuolo, D. Exploring the Potential of Macroalgae for Sustainable Crop Production in Agriculture. Life 2024, 14, 1263.

- Pereira, L. Littoral of Viana do Castelo—ALGAE (Bilingual). Câmara Municipal de Viana do Castelo: Viana do Castelo, Portugal, 2010; 68p, ISBN 978-972-588-217-7.

- Pereira, L. Littoral of Viana do Castelo—ALGAE. Uses in Agriculture, Gastronomy and Food Industry (Bilingual); Câmara Municipal de Viana do Castelo: Viana do Castelo, Portugal, 2010; 68p, ISBN 978-972-588-218-4.

- Kalasariya, H.S.; Yadav, V.K.; Yadav, K.K.; Tirth, V.; Algahtani, A.; Islam, S.; Gupta, N.; Jeon, B.-H. Seaweed-Based Molecules and Their Potential Biological Activities: An Eco-Sustainable Cosmetics. Molecules 2021, 26, 5313.