Dolphin echolocation is a biological sonar system that allows dolphins to navigate, hunt, and communicate in aquatic environments by emitting sound waves and interpreting returning echoes. This capability enables them to determine the distance, size, shape, movement, and even internal structure of objects with remarkable precision.

- dolphin echolocation

- biological sonar system

- dolphin

1. Introduction

Echolocation, or biosonar, represents one of the most sophisticated sensory systems in the animal kingdom. Among mammals, dolphins are especially renowned for their echolocation capabilities, which have evolved as an adaptation to life in often dark or turbid underwater environments. Through the production and interpretation of high-frequency clicks, dolphins can create an auditory representation of their surroundings, enabling precise detection of prey and obstacles.

This ability is primarily associated with toothed whales (Odontoceti), particularly bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus), which have been extensively studied for their acoustic and cognitive abilities [1]. Dolphin echolocation exemplifies convergent evolution, sharing functional parallels with the echolocation systems of bats despite independent evolutionary origins [2].

2. Anatomy of Echolocation

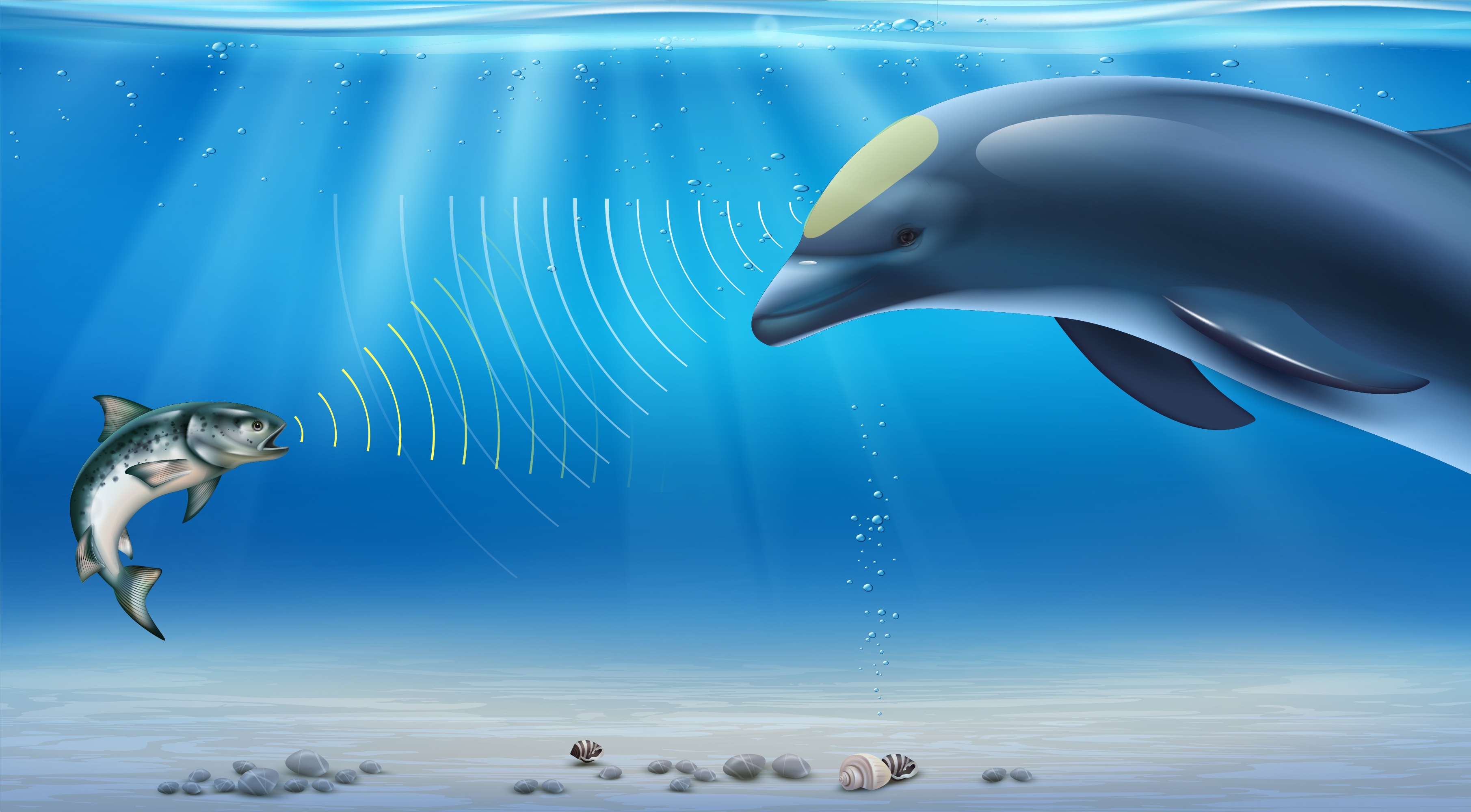

The dolphin’s head contains several specialized anatomical structures that facilitate sound generation, transmission, and reception. The primary sound-producing organ is located within the nasal region and comprises the phonic lips, paired structures that generate broadband clicks when air is forced through them. These sounds are then focused and projected through the melon, a lens-shaped mass of fatty tissue on the forehead that acts as an acoustic lens, collimating and directing the sound beam into the surrounding water [1][3].

Incoming echoes are received through the lower jaw, which contains lipid-filled acoustic channels that transmit sound vibrations to the middle ear bones. These adaptations allow dolphins to detect minute variations in echo delay and amplitude, essential for high-resolution auditory imaging [4]. Unlike terrestrial mammals, dolphins lack external pinnae; instead, they rely on their specialized jaw and internal acoustic pathways for directional hearing.

3. Mechanisms and Sound Production

Echolocation clicks produced by dolphins typically range from 20 kHz to 150 kHz, far beyond the range of human hearing. The precise control of frequency, intensity, and repetition rate allows dolphins to adjust their sonar according to environmental conditions and target distance [1].

The clicks are produced in rapid sequences known as click trains, which may vary in rate depending on behavioral context. During prey pursuit, dolphins emit buzz trains—high-repetition sequences that provide continuous echo feedback for fine-scale tracking.

The time interval between click emission and echo reception allows dolphins to determine the distance of an object with astonishing precision, often within less than 100 microseconds of temporal resolution. This temporal sensitivity enables dolphins to discriminate between targets separated by just a few centimeters.

4. Neural and Cognitive Processing

The dolphin brain is highly adapted for auditory processing. The auditory cortex occupies a substantial proportion of the cerebral hemisphere, reflecting the dominance of acoustic perception in their sensory world.

Neurophysiological studies indicate that dolphins perform real-time analysis of echo delay, amplitude, and frequency modulations. Through cognitive integration, they can reconstruct a three-dimensional spatial map of their surroundings—a process functionally analogous to visual imaging but relying entirely on sound.

Dolphins are capable of object discrimination, material recognition, and even texture identification using echolocation cues. Controlled experiments have demonstrated that dolphins can distinguish between objects made of metal, plastic, and wood solely through echo characteristics, independent of vision [4].

Furthermore, dolphins exhibit neural plasticity in response to echolocation demands, showing adaptive modulation of auditory thresholds and cortical activation patterns under different acoustic environments.

5. Behavioral and Ecological Roles

Echolocation underpins multiple aspects of dolphin ecology, including foraging, navigation, communication, and social coordination.

During foraging, echolocation allows dolphins to detect and track fast-moving fish in murky waters where visibility is limited. Some species, such as the Amazon river dolphin (Inia geoffrensis), rely heavily on echolocation to navigate complex river systems filled with vegetation and sediment.

Group hunting behaviors often involve coordinated sonar scanning, where individuals adjust their echolocation patterns to minimize acoustic interference—a phenomenon known as acoustic partitioning.

Dolphins can also adjust the amplitude and frequency of their clicks based on distance to a target or environmental noise level, a process called the Lombard effect, indicating a sophisticated form of auditory feedback control.

6. Evolutionary Perspectives

The emergence of echolocation in dolphins represents a major evolutionary innovation that arose after their divergence from baleen whales (Mysticeti). Molecular and comparative genomic studies suggest that echolocation evolved through the modification of auditory and neural pathways originally adapted for underwater hearing.

Several genes, such as Prestin (SLC26A5), involved in outer hair cell motility, show signs of convergent evolution in both bats and toothed whales, indicating shared molecular solutions to high-frequency sound detection.

Fossil evidence indicates that early toothed whales from the Oligocene epoch already possessed cranial features associated with directional hearing and sound emission, suggesting an early origin of biosonar capability. The evolutionary success of odontocetes is closely linked to this sensory adaptation, which enabled them to exploit diverse ecological niches in the world’s oceans.

7. Human Applications and Bioinspired Technologies

Research on dolphin echolocation has led to the development of bioinspired sonar and underwater navigation systems. Engineers have applied principles derived from dolphin sonar—such as adaptive beam focusing, broadband frequency modulation, and echo-delay computation—to improve the resolution and efficiency of synthetic sonar devices.

Applications include autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) for ocean exploration, medical ultrasound imaging, and non-invasive detection systems for environmental monitoring.

Artificial intelligence models based on dolphin sonar processing are also used to enhance signal classification and object recognition in complex acoustic environments. These technologies illustrate the growing intersection between marine biology, neuroscience, and engineering.

8. Conservation and Ethical Considerations

Anthropogenic noise poses significant challenges to echolocating marine mammals. Increasing levels of underwater noise from shipping, industrial activities, and naval sonar can disrupt echolocation efficiency, mask communication signals, and cause stress or behavioral disorientation.

Chronic exposure to high-intensity sounds may lead to temporary or permanent hearing threshold shifts, affecting survival and reproductive success.

Conservation efforts therefore emphasize noise mitigation strategies, such as establishing marine acoustic sanctuaries, regulating sonar use, and adopting quieting technologies in vessels.

Ethical considerations also extend to the study of captive dolphins. Researchers advocate minimizing invasive testing and ensuring enrichment conditions that allow for natural echolocation behaviors.

9. Conclusion

Dolphin echolocation is an extraordinary sensory adaptation that integrates anatomical specialization, neural computation, and behavioral intelligence. This biosonar system exemplifies the evolutionary ingenuity of marine mammals and continues to inspire technological innovation.

Ongoing research combining molecular genetics, neuroimaging, and bioacoustics promises to further illuminate how dolphins perceive their world through sound—and how humans may continue to learn from their remarkable capabilities.

References

- Au, W. W. L., & Hastings, M. C. Principles of Marine Bioacoustics. Springer, 2008. DOI: 10.1007/978-0-387-78365-9.

- Madsen, P. T., & Surlykke, A. Functional Convergence in Bat and Toothed Whale Echolocation. Physiology 2013, 28(5), 276–283. DOI: 10.1152/physiol.00008.2013.

- Au, W. W. L. The Sonar of Dolphins. Springer Handbook of Auditory Research 1993, Springer-Verlag. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4612-4356-4.

- Johnson, M., & Tyack, P. L. A Digital Acoustic Recording Tag for Measuring the Response of Wild Marine Mammals to Sound. IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering 2003, 28(1), 3–12. DOI: 10.1109/JOE.2002.808212.