Pro-inflammatory cytokines released from tumor cells or stromal cells act in both autocrine and paracrine manners to induce phenotype changes in tumor cells, recruit bone marrow-derived cells, and form an inflammatory milieu, all of which prime a secondary organ’s microenvironment for metastatic cell colonization.

- pre-metastatic niche,pro-inflammatory cytokines

1. Introduction

Tumor metastasis is the main cause of therapeutic failure and mortality, with few effective treatment options. It has been suggested that the tumor microenvironment plays a prominent role in the formation of metastasis, collaborating with genetic and epigenetic networks in cancer cells [1,2]. A key step for the formation of tumor metastases is the extravasation of circulating tumor cells into distant organs and their adaption to new environments. Therefore, the reciprocal interactions between to the disseminated cancer cells and the microenvironment in distant organs are imperative to successful metastasis. Primary tumor cells orchestrate the metastasis process through secreting a variety of molecules which promote the mobilization and recruitment of various types of cells to the premetastatic sites and alter the expression of matrix proteins and the properties of the extracellular matrix (ECM) in secondary organs. All these events help create the so-called pre-metastatic niche (PMN), suitable for the engraftment of metastasizing tumor cells. The concept of PMN was first proposed by Dr. David Lyden in 2005 [3]. Since then, targeting the PMN to prevent metastasis has become a promising strategy for cancer treatment. However, much remains to be revealed about the factors that facilitate the establishment of the implantation site for tumor metastasis.

Priming of the organ-specific premetastatic sites is an important yet incompletely understood step during metastasis formation. Bone marrow-derived cells (BMDCs) and tumor-derived secreted factors are the two crucial components for pre-metastatic niche formation. The main type of BMDCs accumulated in the pre-metastatic niche is myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). When infections and tissue injuries occur, the myeloid lineage is promptly expanded, and myeloid leukocytes in the bone marrow perform a protective role in host defense against such stresses and traumas. However, chronic inflammation associated with cancer induces the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines that drive the differentiation of myeloid cells towards MDSCs. MDSCs are a heterogeneous population of immature myeloid cells including macrophages, granulocytes, neutrophiles, and dendritic cells. They accumulate in the circulation of cancer patients and are recruited to peripheral lymphoid organs and tumor sites by growth factors released by cancer cells. Within the tumor microenvironment, MDSC were shown to inhibit the proliferation and activity of killer T cells, promote angiogenesis, and improve tumor cells survival, thereby promoting tumor invasion and metastasis [4]. Besides the recruited MDSCs, the host stromal environment of the PMN also includes fibroblast, endothelial cells, and ECM.

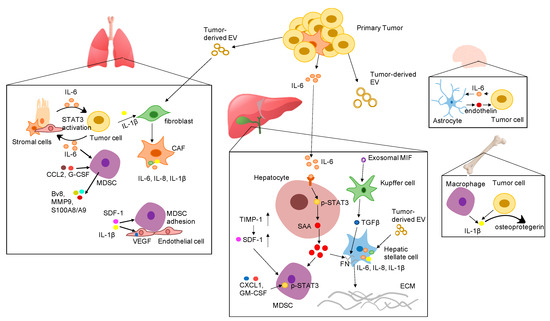

Tumor-derived secreted factors play important roles in preparing distant organs for pre-metastatic niche formation. Tumor-derived secreted factors include cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, and extracellular vesicles (EV). Cytokines are a diverse family of small proteins secreted by cells, predominantly by helper T cells and macrophages for cell-to-cell communication. Cytokines could act on the cells releasing them (autocrine action), on nearby cells (paracrine action), or on distant cells (endocrine action) and are often produced in a cascade, as one cytokine stimulates its target cells to produce additional cytokines. The major subgroups of cytokines include interleukins, interferons, colony-stimulating factors, chemokines, and tumor necrosis factors. Cytokines exert their effects through binding to cytokine receptors on target cells, which activates a sequence of downstream proteins for the desired responses. It should be noted that the effects of different cytokines are sometimes redundant, with different cytokines eliciting similar responses [5,6]. Cytokines play a key role in tumor progression and metastasis by either directly regulating tumor growth, invasiveness, and metastasis or indirectly affecting stromal cells and immune cells [7]. Accumulating evidence suggests that pro-inflammatory cytokines are pivotal in the formation of the pre-metastatic niche. Tumor cell-derived pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines recruit a variety of regulatory and suppressive immune cells into distant sites to prime the local environment. The proliferative and invasive abilities of disseminated cancer cells are enhanced by proinflammatory cytokines from the surrounding microenvironment as paracrine signals. Thus, cancer cells can undergo epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) to grow in distant tissues. In this review, we focus on the role of important pro-inflammatory cytokines in the establishment of the PMN and highlight the underlying mechanisms of PMN formation in various organs based on the most recent studies (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Proposed mechanisms by which various pro-inflammatory cytokines promote the formation of the pre-metastatic niche in different organs. Abbreviation: EV: extracellular vesicles; IL-6: interleukin 6; IL-1β: interleukin-1β; SDF-1 α: stromal cell-derived factor 1; IL-8: interleukin 8; VEGF: vascular endothelial growth factor; G-CSF: granulocyte-colony stimulating factor; CCL2: CC-chemokine ligand 2; CXCL1: C-X-C motif ligan 1; MIF: macrophage migration inhibitory factor; TIMP-1: tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1; GM-CSF: granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; SAA: serum amyloid A; TGF-β: transforming growth factor beta; FN: fibronectin; ECM: extracellular matrix; STAT3: signal transducer and activator of transcription 3; CAF: cancer associated fibroblast; MDSC: myeloid-derived suppressor cells.

2. Clinical Trials Targeting Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines in Metastatic Cancer

Pro-inflammatory cytokines are key mediators of innate and adaptive immunity at the crossroad of diverse pathways shaping pre-metastatic niches. Nowadays, several agents targeting IL-6, IL-6 receptor, JAKs, or STAT3 have been used in the treatment of myeloma and tested in patients with solid tumors [8,59]. There are two FDA-approved antibodies directly targeting IL-6: siltuximab, a chimeric anti-IL-6 antibody [60], and tocilizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody against the IL-6 receptor. Various global clinical trials, series, and pilot studies of off-label use of siltuximab and tocilizumab provide strong indications [61] that the anti-IL-6 therapy may be used for the treatment of blood cancers such as multiple myeloma [62] and leukemia [63] and of solid tumors such as prostate cancer [64], breast cancer [65], and ovarian cancer [66]. However, two phase II trials which employed siltuximab as second-line therapy for patients with metastatic prostate cancer showed an increase in plasma IL-6 after treatment and confirmed the poor prognosis associated with elevated IL-6 [60,67]. Two clinical trials, one (NCT04191421) evaluating siltuximab in metastatic pancreatic cancer patients and the other (NCT03135171) evaluating tocilizumab in metastatic HER2-postive breast cancer patients are in progress (Table 1).

| Tested Drug | NCT Number | Title | Status | Conditions | Phases | Enrollment | Start Date | Completion Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 pathway | ||||||||

| IL-6 | ||||||||

| Siltuximab, anti-IL-6 chimeric monoclonal antibody | NCT00433446 | S0354, Anti-IL-6 Chimeric Monoclonal Antibody in Patients with Metastatic Prostate Cancer That Did Not Respond to Hormone Therapy | Completed | Metastatic Prostate Cancer | Phase 2 | 62 | 2007 | 2011 |

| NCT00385827 | A Safety and Efficacy Study of Siltuximab (CNTO 328) in Male Subjects with Metastatic Hormone-Refractory Prostate Cancer (HRPC) | Terminated | Metastatic Prostate Cancer | Phase 2 | 106 | 2017 | 2021 | |

| NCT04191421 | Siltuximab and Spartalizumab in Patients with Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer | Recruiting | Metastatic Stage IV Pancreatic Cancer | Phase 1|Phase 2 | 42 | 2020 | 2022 | |

| Tocilizumab, humanized monoclonal antibody against IL-6 receptor | NCT03135171 | Trastuzumab and Pertuzumab in Combination with Tocilizumab in Subjects with Metastatic HER2-Positive Breast Cancer Resistant to Trastuzumab | Recruiting | HER2+ Breast Cancer | Phase 1 | 20 | 2017 | 2021 |

| JAK | ||||||||

| Ruxolitinib, JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitor | NCT00638378 | Study of Ruxolitinib (INCB018424) Administered Orally to Patients with Androgen-Independent Metastatic Prostate Cancer | Terminated | Prostate Cancer | Phase 2 | 22 | 2008 | 2009 |

| NCT01594216 | Ruxolitinib in Estrogen Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer | Completed | Estrogen Receptor-Positive Invasive Metastatic Breast Cancer | Phase 2 | 29 | 2012 | 2016 | |

| NCT02120417 | A Study of Ruxolitinib in Combination with Capecitabine in Subjects with Advanced or Metastatic HER2-Negative Breast Cancer | Terminated | Breast Cancer | Phase 2 | 149 | 2014 | 2017 | |

| NCT02041429 | Ruxolitinib W/Preop Chemo for Triple-Negative Inflammatory Breast cancer | Active, not recruiting | Recurrent Breast Cancer| Metastatic Breast Cancer | Phase 1|Phase 2 | 24 | 2014 | 2021 | |

| NCT02066532 | Ruxolitinib in Combination with Trastuzumab in Metastatic HER2-Positive Breast Cancer | Active, not recruiting | Metastatic Breast Cancer|HER-2 Positive Breast Cancer | Phase 1|Phase 2 | 28 | 2014 | 2020 | |

| NCT03012230 | Pembrolizumab and Ruxolitinib Phosphate in Treating Patients with Metastatic Stage IV Triple-Negative Breast Cancer | Recruiting | Metastatic Malignant Neoplasm in the Bone Stage IV Breast Cancer|Triple-Negative Breast Carcinoma | Phase 1 | 18 | 2017 | 2021 | |

| NCT02876302 | Study of Ruxolitinib (INCB018424) With Preoperative Chemotherapy for Triple-Negative Inflammatory Breast Cancer | Recruiting | Inflammatory Breast Cancer | Phase 2 | 64 | 2017 | 2024 | |

| Itacitinib, JAK1 inhibitor | NCT03670069 | Itacitinib in Treating Patients with Refractory Metastatic/Advanced Soft Tissue Sarcomas | Recruiting | Metastatic Leiomyosarcoma|Metastatic Synovial Sarcoma | Phase 1 | 28 | 2019 | 2022 |

| STAT | ||||||||

| BBI608, STAT3 inhibitor | NCT03522649 | A Phase III Clinical Study of Napabucasin (GB201) Plus FOLFIRI in Adult Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer | Recruiting | Previously Treated Metastatic Colorectal Cancer | Phase 3 | 668 | 2018 | 2021 |

| NCT03647839 | Modulation of The Tumor Microenvironment Using Either Vascular Disrupting Agents or STAT3 Inhibition in Order to Synergize With PD1 Inhibition in Microsatellite-Stable, Refractory Colorectal Cancer Patients | Active, not recruiting | Colorectal Cancer Metastatic | Phase 2 | 90 | 2018 | 2022 | |

| WP1066, JAK2/STAT3 inhibitor | NCT01904123 | STAT3 Inhibitor WP1066 in Treating Patients with Recurrent Malignant Glioma or Progressive Metastatic Melanoma in the Brain | Recruiting | Metastatic Malignant Neoplasm in the Brain| Metastatic Melanoma | Phase 1 | 33 | 2018 | 2021 |

| NCT04334863 | AflacST1901: Peds WP1066 | Recruiting | Brain Tumor|Medulloblastoma|BrainMetastases | Phase 1 | 36 | 2020 | 2023 | |

| IL-1 | ||||||||

| Canakinumab, human anti-IL-1β monoclonal antibody | NCT03631199 | Study of Efficacy and Safety of Pembrolizumab Plus Platinum-based Doublet Chemotherapy with or without Canakinumab in Previously Untreated Locally Advanced or Metastatic Non-Squamous and Squamous Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) Subjects | Active, not recruiting | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | Phase 3 | 673 | 2018 | 2022 |

| NCT04581343 | A Phase 1B Study of Canakinumab, Spartalizumab, Nab-Paclitaxel, and Gemcitabine in Metastatic PC Patients | Recruiting | Metastatic Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma | Phase 1 | 10 | 2020 | 2022 | |

| Anakinra, human interleukin 1 receptor antagonist | NCT00072111 | Anakinra in Treating Patients with Metastatic Cancer Expressing the Interleukin-1 Gene | Completed | Metastatic Cancer | Phase 1 | 2003 | 2015 | |

| NCT02090101 | Study Evaluating the Influence of LV5FU2 Bevacizumab Plus Anakinra Association on Metastatic Colorectal Cancer | Completed | Metastatic Colorectal Cancer | Phase 2 | 32 | 2014 | 2017 | |

| NCT01802970 | Safety and Blood Immune Cell Study of Anakinra Plus Physician’s Chemotherapy Choice in Metastatic Breast Cancer Patients | Completed | Metastatic Breast Cancer | Phase 1 | 10 | 2012 | 2017 | |

| NCT01624766 | Everolimus and Anakinra or Denosumab in Treating Participants with Relapsed or Refractory Advanced Cancers | Active, not recruiting | Advanced Malignant Neoplasm|Metastatic Malignant Neoplasm|Recurrent Malignant Neoplasm|Refractory Malignant Neoplasm | Phase 1 | 57 | 2012 | 2020 | |

| CCL2 | ||||||||

| Carlumab | NCT00992186 | A Study of the Safety and Efficacy of Single-Agent Carlumab (an Anti-Chemokine Ligand 2 [CCL2]) in Participants with Metastatic Castrate-Resistant Prostate Cancer | Completed | Prostate cancer | Phase 2 | 46 | 2009 | 2011 |

| CSF | ||||||||

| SNDX-6352, CSF receptor inhibitor | NCT03238027 | A Phase 1 Study to Investigate SNDX-6352 Alone or in Combination With Durvalumab in Patients With Solid Tumors | Active, not recruiting | Solid Tumor|Metastatic Tumor | Phase 1 | 45 | 2017 | 2021 |

| SDF-1 | ||||||||

| Olaptesed, binding to SDF-1 | NCT03168139 | Olaptesed (NOX-A12) Alone and in Combination with Pembrolizumab in Colorectal and Pancreatic Cancer Patients | Completed | Metastatic Colorectal Cancer|Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer | Phase 1|Phase 2 | 20 | 2017 | 2020 |

| MIF | ||||||||

| Anti-MIF antibody | NCT01765790 | Phase 1 Study of Anti-Macrophage Migration Inhibitory Factor (Anti-MIF) Antibody in Solid Tumors | Completed | Metastatic Adenocarcinoma of the Colon or Rectum | Phase 1 | 68 | 2012 | 2016 |

Downstream in the IL-6 signaling pathway, JAK is another important drug target for cancer treatment. Among various JAK inhibitors, ruxolitinib is the most extensively investigated for cancer treatment. Approved by the FDA in 2011 for the treatment of myelofibrosis and post-polycythemia vera, ruxolitinib is a potent and selective oral JAK1 and JAK2 inhibitor. Studies on the safety and effectiveness of ruxolitinib in cancer patients with solid tumors such as breast cancer (NCT01594216, lung cancer (NCT02145637), colorectal cancer (NCT04303403), pancreatic cancer (NCT04303403), and head and neck cancer (NCT03153982) are ongoing. Additional early-phase trials of ruxolitinib have been focused on cancer metastasis, including patients with metastatic prostate cancer and metastatic breast cancer, as listed in Table 1. However, two phase III trials (NCT02119663 and NCT02117479) of ruxolitinib with capecitabine in metastatic pancreatic cancer patients were terminated due to no additional benefit over capecitabine alone [68]. The same also occurred with a phase II trial of ruxolitinib with capecitabine in patients with metastatic HER2-postive breast cancer (NCT02120417). Besides ruxolitinib, itacitinib, a JAK1 specific inhibitor, has also been employed in a phase I trial of metastatic soft tissue sarcomas.

The third potential target in the IL-6 signaling pathway is STAT3, with several compounds inhibiting the function or expression of STATs in clinical trials for various solid tumors [69]. BBI608, an oral cancer stemness inhibitor that blocks STAT3-mediated transcription of cancer stemness genes in the β-catenin pathway, has reached Phase II and III to treat metastatic colorectal cancer (Table 1). WP1066, a novel STAT3 inhibitor first published in 2010 [70], is in phase I for malignant glioma, metastatic melanoma in the brain, and pediatric brain tumors (Table 1).

Similarly, IL-1-blocking therapies have also been implicated in cancer-related inflammation [38,39]. Currently, clinically available anti-IL-1 strategies include anakinra (IL-1 receptor antagonist), canakinumab (a human anti-IL-1β monoclonal antibody), CAN04 (an IL-1 receptor accessory protein binding protein), and isunakinra (a potent IL-1 receptor inhibitor). Accumulated evidence indicated that canakinumab is highly promising for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer, for which clinical trials are ongoing (NCT02090101, NCT01802970). Canakinumab is also being evaluated in metastatic pancreatic cancer, in a phase I clinical trial (Table 1). Another important anti-IL-1 drug for cancer treatment is anakinra, which is widely used to treat autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases. It is also being tested as an adjunct therapy to reduce the inflammation associated with metastatic cancer, including colorectal cancer and breast cancer (Table 1).

In 2009, a phase II clinical trial has been conducted to test the effect of carlumab, a human mAb with high affinity and specificity for human CCL2, in patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. In this trial, carlumab was unable to sustain a durable suppression of CCL2 and could not lead to meaningful clinical benefit responses (Table 1) [71]. Notably, the clinical application of CCL2 inhibitors for metastasis treatment requires a careful design.

Besides the extensively studied IL-6 and IL-1β, there are several early-phase clinical trials exploring the efficacy of targeting CSF, SDF-1, and MIF in the treatment of various metastatic tumors, as summarized in Table 1. The trials with SDF-1 and MIF have been completed, but no results have been reported yet.

3. Conclusions

Cancer metastasis poses significant challenges to the development of curative therapies due to insufficient knowledge of the mechanisms governing this process. Targeting the molecular interactions that build the PMN has the potential to prevent and eradicate metastases before they manifest. It would be most useful to block the signaling systems that promote the establishment of the PMN right after dissecting a primary tumor, i.e., in the critical post-operative window when no visible metastases are observed but PMN formation is probably ongoing. Compelling evidence implies the rise of pro-inflammatory cytokines and the suppression of the immune function during the peri-operative and post-operative periods [72,73], which all contribute to PMN formation. However, the combination of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the PMN is still under investigation and may vary in different types of cancer or even in individual patients. The advanced ‘omics’ technology could help design more precise and individualized therapeutic approaches in future clinical trials. Admittedly, some clinical trials targeting IL-6 or IL-1 have failed in preventing metastasis. Human solid tumors are more complex than mouse models, and the heterogeneity of cancer cells could be a factor affecting treatment efficacy. Thus, monotherapy to inhibit a single cytokine may not be sufficient to treat advanced tumors. Taking in consideration the pleiotropy and redundancy of pro-inflammatory cytokines, further in vitro and in vivo studies should be designed to determine the joint power of pro-inflammatory cytokines in PMN formation, as well as to analyze their combined targeting in cancer metastasis.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers12123752