Archard’s wear law is among the first and foremost wear models derived from contact mechanics that relates key operating conditions and material hardness to sliding wear through a multifaceted wear coefficient. This entry explores the development, generalization, and critique of the Archard model—a foundational model in wear prediction. It outlines the historical origins of the model, its basis in contact plasticity, and its use of a constant wear coefficient. The discussion highlights modern efforts to extend the model through variable exponents and empirical calibration. Key limitations such as the oversimplification of wear behavior, exclusion of factors like sliding velocity, and scale sensitivity are examined through both theoretical arguments and experimental evidence. The critiques reflect the model’s constrained applicability in diverse wear conditions across varied operating conditions and material phenomena.

- wear

- Archard’s wear law

- wear data

- wear modeling

-

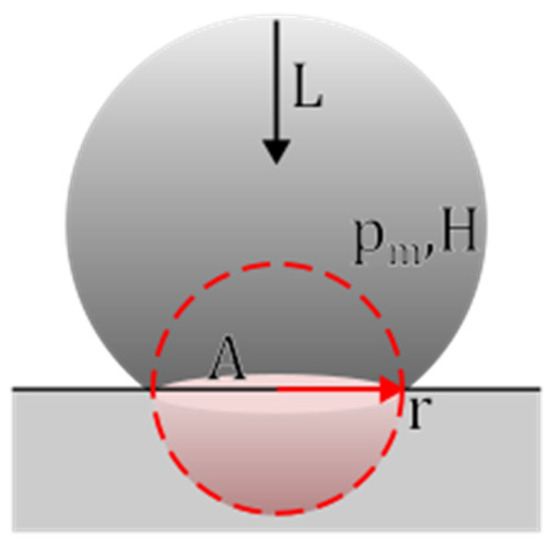

The geometric transformation from original surface asperities to the plastically deformed contact area that generates wear;

-

The relationship between yield strength and hardness;

-

The fraction of plastic deformation that contributes to material loss;

-

The likelihood that material can be removed from the contact interface;

-

The contributions of other factors (e.g., temperature, surface tribochemical activities, lubrication, etc.) not explicitly included by Equation (1) but empirically linked to wear.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/encyclopedia5030124

References

- Meng, H.C.; Ludema, K.C. Wear Models and Predictive Equations: Their Form and Content. Wear 1995, 181, 443–457.

- Archard, J.F. Contact and Rubbing of Flat Surfaces. J. Appl. Phys. 1953, 24, 981–988.

- Holm, R. Electric Contacts; Almquist and Wiksells: Stockholm, Sweden, 1946.

- Halling, J. Principles of Tribology; The Macmillan Press LTD: London, UK, 1975.

- Timsit, R.S. Course on Performance and Reliability of Power Electrical Connections. In Electrical Contacts: Principles and Applications; Slade, P.G., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014.

- Wang, Q.J.; Chung, Y.-W. Encyclopedia of Tribology; Springer US: New York, NY, USA, 2013.

- Liu, Y.; Liskiewicz, T.W.; Beake, B.D. Dynamic Changes of Mechanical Properties Induced by Friction in the Archard Wear Model. Wear 2019, 428, 366–375.

- Molinari, J.; Aghababaei, R.; Brink, T.; Frérot, L.; Milanese, E. Adhesive Wear Mechanisms Uncovered by Atomistic Simulations. Friction 2018, 6, 245–259.

- Delaney, B.C.; Wang, Q.J.; Aggarwal, V.; Chen, W.; Evans, R.D. A Contemporary Review and Data-Driven Evaluation of Archard-Type Wear Laws. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2025, 77, 022101 .