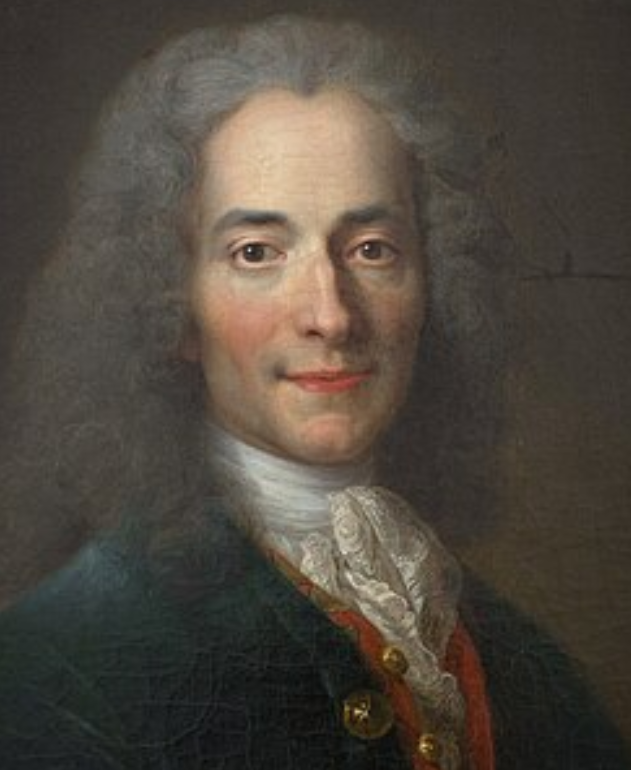

Voltaire was the pen name of François-Marie Arouet, a French Enlightenment writer, historian, and philosopher renowned for his wit, intellectual prowess, and vigorous criticism of institutional authority, particularly the Church and the French monarchy. He is considered one of the most significant voices of the Enlightenment era, advocating for reason, civil liberties, and secular governance. Voltaire's literary legacy includes satirical novels, historical works, philosophical treatises, and thousands of letters that shaped the development of modern thought.

- Voltaire

- François-Marie Arouet

- French literature

1. Early Life and Education

Voltaire was born on November 21, 1694, in Paris, the youngest of five children to a middle-class family. His father, François Arouet, was a notary, while his mother, Marie Marguerite d'Aumart, hailed from a noble lineage. Despite a strained relationship with his father—who wished his son to pursue a legal career—Voltaire gravitated towards literature and philosophy from an early age [1].

He was educated at the Collège Louis-le-Grand, a Jesuit institution in Paris known for its rigorous classical curriculum. There, he studied Latin, rhetoric, theology, and philosophy, absorbing the intellectual traditions of antiquity and early modern Catholic scholasticism. Voltaire excelled in literature and quickly became known for his sharp wit, biting humor, and critical essays [2].

By Nicolas de Largillière - Voltaire.jpg, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5266773

Following his schooling, he briefly studied law to please his father but soon abandoned it to immerse himself in Parisian literary and intellectual circles.

2. Satire, Imprisonment, and the Birth of “Voltaire”

Voltaire's early career was marked by his incisive satire, which targeted noblemen, clerics, and political elites. In 1717, he was imprisoned in the Bastille for composing verses that mocked the Duke of Orléans, then the regent of France. He spent nearly a year incarcerated, during which he began to develop the philosophical stance and literary identity that would define his career [3].

Upon his release in 1718, he adopted the pseudonym “Voltaire.” The origin of the name remains debated; some scholars suggest it is an anagram of “Arouet le Jeune” (AROVET LI), while others believe it was meant to distinguish his literary persona from his family name [4].

His first dramatic success came that same year with the tragedy Œdipe, which received acclaim for its classical themes and elegant verse. This success gained him admission to elite Parisian salons and royal favor.

3. Exile in England and Enlightenment Transformation (1726–1729)

Voltaire's rising fame and persistent mockery of the aristocracy led to another confrontation in 1726, when he quarreled with Chevalier de Rohan. Following a public beating orchestrated by Rohan’s retainers, Voltaire retaliated with harsh words, prompting his re-arrest. He chose exile in England over imprisonment and arrived in London in May 1726.

Voltaire spent nearly three years in England, and this period proved transformative. He immersed himself in English political philosophy, Newtonian science, literature, and religious pluralism, developing a deep admiration for the British constitutional monarchy and its relatively free press [5].

Voltaire befriended leading intellectuals, including Alexander Pope, Jonathan Swift, and Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, and he read works by John Locke, Isaac Newton, and Francis Bacon. These thinkers profoundly influenced his ideas about empiricism, liberty, and tolerance.

4. Return to France and the Lettres philosophiques

In 1729, Voltaire returned to France and began writing one of his most influential works, the Lettres philosophiques (Letters on the English), published in 1734. This epistolary work compared English and French institutions, highlighting England’s religious tolerance, scientific rationalism, and freedom of thought, while criticizing French absolutism and clerical domination [6].

The book provoked the wrath of the French authorities. Copies were burned, and a warrant was issued for Voltaire’s arrest. He fled Paris, taking refuge in Champagne with his companion Émilie du Châtelet, a brilliant mathematician and physicist.

5. Scientific Inquiry and Collaboration with Émilie du Châtelet

From 1734 to 1749, Voltaire lived with du Châtelet at her estate in Cirey, where the two collaborated intellectually. Du Châtelet translated Newton’s Principia Mathematica into French, while Voltaire authored the Éléments de la philosophie de Newton (1738), introducing Newtonian physics to the French public and challenging Cartesian orthodoxy [7].

Their partnership bridged Enlightenment philosophy and empirical science, and Cirey became a hub of intellectual activity.

6. Historical Works and Royal Engagements

Voltaire also made significant contributions to historical writing, seeking to analyze human events rationally and critically. His Histoire de Charles XII (1731) and Le Siècle de Louis XIV (1751) departed from providential history and emphasized human agency, political context, and cultural achievements.

In 1746, Voltaire was elected to the Académie Française, and two years later, he accepted an invitation from Frederick the Great of Prussia to stay at Potsdam, where he served briefly as court philosopher. However, their relationship soured over ideological and personal differences, and Voltaire returned to France in 1753 [8].

7. Candide and Philosophical Satire

In 1759, Voltaire published his most celebrated work, Candide, ou l’Optimisme, a philosophical novella that lampooned Leibnizian optimism—particularly the idea that we live in “the best of all possible worlds.” Through the misadventures of the naive protagonist, Candide, Voltaire attacked war, religious persecution, colonialism, and natural disaster [9].

The Lisbon earthquake of 1755 deeply influenced this work, leading Voltaire to challenge theological explanations for human suffering.

Candide was both banned and wildly popular, selling tens of thousands of copies despite censorship. It remains a classic of philosophical literature and Enlightenment critique.

8. Religious Tolerance and the Calas Affair

Voltaire’s advocacy for justice and tolerance became most evident in his activism during the Calas Affair (1762). Jean Calas, a Protestant, was falsely accused and executed for allegedly murdering his son to prevent a Catholic conversion. Voltaire campaigned to clear Calas’s name, exposing judicial bias and religious bigotry.

His writings, including the Traité sur la tolérance (Treatise on Tolerance, 1763), argued for freedom of religion, legal reform, and rational jurisprudence. He also defended other victims of injustice, such as Pierre-Paul Sirven and Chevalier de La Barre, who was executed for impiety [10].

These efforts helped shape Enlightenment ideals of universal rights, due process, and freedom of conscience.

9. Later Years at Ferney and Intellectual Influence

From 1759 to 1778, Voltaire lived in Ferney, near the French-Swiss border. His estate became a center of philosophical correspondence, visited by thinkers, reformers, and nobility from across Europe.

Voltaire continued to write prolifically—producing plays, pamphlets, poems, and philosophical essays. He supported civil engineering, education, improved agriculture, and social reform in the region. His role as a "benevolent despot" of Ferney exemplified Enlightenment ideals applied locally.

He corresponded with Catherine the Great, Frederick the Great, Benjamin Franklin, and many others, exerting a pan-European influence.

10. Return to Paris and Death

After nearly three decades away from the capital, Voltaire returned to Paris in February 1778 to see the premiere of his play Irène. He was greeted with adoration, crowned with laurels at the Comédie-Française, and hailed as a living legend of the Enlightenment.

Voltaire died on May 30, 1778, shortly after his triumphant return. Because of his anti-clericalism, the Church initially denied him a Christian burial. However, in 1791, his remains were exhumed and interred in the Panthéon as a national hero of revolutionary France.

11. Philosophy and Legacy

Voltaire's philosophy emphasized:

-

Freedom of thought and expression;

-

Opposition to dogma and superstition;

-

Promotion of reason and science;

-

Critique of absolute monarchy and organized religion;

-

Advocacy for judicial reform and civil rights.

He was not a systematic philosopher like Kant or Hume, but his practical engagement with political injustice made him a moral philosopher of the Enlightenment.

Voltaire’s writings laid the intellectual groundwork for the French Revolution and modern secular democracy. His aphorisms and literary style continue to influence debates on free speech, tolerance, and human rights.

12. Conclusion

Voltaire stands as one of the most influential thinkers in Western history. Through his fearless critique of oppression and unwavering belief in human reason, he challenged the very foundations of the ancien régime. His wit, irony, and literary genius remain vibrant, ensuring his enduring relevance in discussions about freedom, justice, and truth.

References

- Pearson, Roger. Voltaire Almighty: A Life in Pursuit of Freedom. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2005.

- Gray, Ian. The Life and Times of Voltaire. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1963.

- Cronk, Nicholas. “Voltaire.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Spring 2023 Edition. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/voltaire/

- Gay, Peter. The Enlightenment: An Interpretation. Vol. 1, Harvard University Press, 1966.

- Braider, Christopher. The Matter of Mind: Reason and Experience in the Age of Descartes. University of Toronto Press, 2008.

- Hitchens, Christopher. Letters to a Young Contrarian. Basic Books, 2001.

- du Châtelet, Émilie. Foundations of Physics. Translated by Judith P. Zinsser, Rutgers University Press, 2009.

- Besterman, Theodore. Voltaire. Harcourt, Brace, 1969.

- Voltaire. Candide, or Optimism. Translated by Theo Cuffe. Penguin Classics, 2005.

- Popkin, Richard H. The Columbia History of Western Philosophy. Columbia University Press, 1999.