Oral Potentially Malignant Disorder (OPMD) is a significant concern for clinicians due to the risk of malignant transformation. Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC) is a common type of cancer with a low survival rate, causing over 200,000 new cases globally each year. Despite advancements in diagnosis and treatment, the five-year survival rate for OSCC patients remains under 50%. Early diagnosis can greatly improve the chances of survival. Therefore, understanding the development and transformation of OSCC and developing new diagnostic methods is crucial. The field of oral medicine has been advanced by technological and molecular innovations, leading to the integration of new medical technologies into dental practice.

- Oral Potentially Malignant Disorders

- OPMD

- Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma

- OSCC

- oral cancer

- imaging technique

- biomarkers

1. Introduction

2. Oral Potentially Malignant Disorders

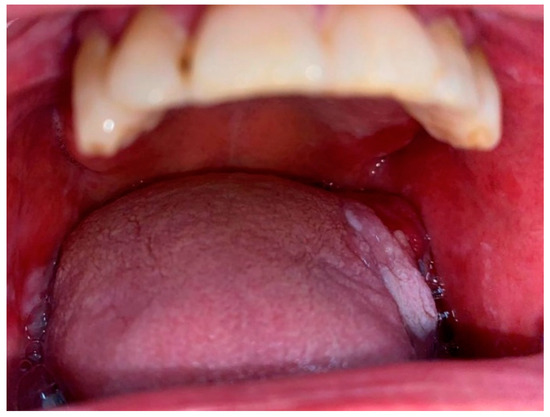

2.1. Oral Leukoplakia, Proliferative Verrucous Leukoplakia and Erythroplakia

2.2. Oral Lichen Planus

2.3. Submucosal Fibrosis

2.4. Actinic Keratosis

2.5. Graft versus Host Disease

3. Oral Malignancies

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/bioengineering11030228

References

- Melsen, B. Tissue Reaction and Biomechanics. Front. Oral Biol. 2016, 18, 36–45.

- Sbordone, C.; Toti, P.; Brevi, B.; Martuscelli, R.; Sbordone, L.; di Spirito, F. Computed Tomography-Aided Descriptive Analysis of Maxillary and Mandibular Atrophies. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 120, 99–105.

- Minervini, G.; Romano, A.; Petruzzi, M.; Maio, C.; Serpico, R.; Lucchese, A.; Candotto, V.; di Stasio, D. Telescopic Overdenture on Natural Teeth: Prosthetic Rehabilitation on (OFD) Syndromic Patient and a Review on Available Literature. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2018, 32 (Suppl. S1), 131–134.

- Contaldo, M.; Luzzi, V.; Ierardo, G.; Raimondo, E.; Boccellino, M.; Ferati, K.; Bexheti-Ferati, A.; Inchingolo, F.; di Domenico, M.; Serpico, R.; et al. Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaws and Dental Surgery Procedures in Children and Young People with Osteogenesis Imperfecta: A Systematic Review. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 121, 556–562.

- Minervini, G.; Nucci, L.; Lanza, A.; Femiano, F.; Contaldo, M.; Grassia, V. Temporomandibular Disc Displacement with Reduction Treated with Anterior Repositioning Splint: A 2-Year Clinical and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) Follow-Up. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2020, 34 (Suppl. S1), 151–160.

- Contaldo, M.; Fusco, A.; Stiuso, P.; Lama, S.; Gravina, A.G.; Itro, A.; Federico, A.; Itro, A.; Dipalma, G.; Inchingolo, F.; et al. Oral Microbiota and Salivary Levels of Oral Pathogens in Gastro-Intestinal Diseases: Current Knowledge and Exploratory Study. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 1064.

- Contaldo, M.; Lucchese, A.; Romano, A.; della Vella, F.; di Stasio, D.; Serpico, R.; Petruzzi, M. Oral Microbiota Features in Subjects with Down Syndrome and Periodontal Diseases: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9251.

- Contaldo, M.; Lucchese, A.; Lajolo, C.; Rupe, C.; di Stasio, D.; Romano, A.; Petruzzi, M.; Serpico, R. The Oral Microbiota Changes in Orthodontic Patients and Effects on Oral Health: An Overview. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 780.

- Contaldo, M.; Itro, A.; Lajolo, C.; Gioco, G.; Inchingolo, F.; Serpico, R. Overview on Osteoporosis, Periodontitis and Oral Dysbiosis: The Emerging Role of Oral Microbiota. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6000.

- Rebelo, M.B.; Oliveira, C.S.; Tavaria, F.K. Novel Strategies for Preventing Dysbiosis in the Oral Cavity. Front. Biosci. 2023, 15, 23.

- di Spirito, F.; Toti, P.; Pilone, V.; Carinci, F.; Lauritano, D.; Sbordone, L. The Association between Periodontitis and Human Colorectal Cancer: Genetic and Pathogenic Linkage. Life 2020, 10, 211.

- Contaldo, M.; della Vella, F.; Raimondo, E.; Minervini, G.; Buljubasic, M.; Ogodescu, A.; Sinescu, C.; Serpico, R. Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale (ECOHIS): Literature Review and Italian Validation. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2020, 18, 396–402.

- Paoletti, I.; Fusco, A.; Grimaldi, E.; Perillo, L.; Coretti, L.; di Domenico, M.; Cozza, V.; Lucchese, A.; Contaldo, M.; Serpico, R.; et al. Assessment of Host Defence Mechanisms Induced by Candida Species. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2013, 26, 663–672.

- Milillo, L.; lo Muzio, L.; Carlino, P.; Serpico, R.; Coccia, E.; Scully, C. Candida-Related Denture Stomatitis: A Pilot Study of the Efficacy of an Amorolfine Antifungal Varnish. Int. J. Prosthodont. 2005, 18, 55–59.

- Contaldo, M.; Romano, A.; Mascitti, M.; Fiori, F.; della Vella, F.; Serpico, R.; Santarelli, A. Association between Denture Stomatitis, Candida Species and Diabetic Status. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2019, 33 (Suppl. S1), 35–41.

- di Stasio, D.; Lauritano, D.; Minervini, G.; Paparella, R.S.; Petruzzi, M.; Romano, A.; Candotto, V.; Lucchese, A. Management of Denture Stomatitis: A Narrative Review. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2018, 32 (Suppl. S1), 113–116.

- Lucchese, A.; di Stasio, D.; Romano, A.; Fiori, F.; de Felice, G.P.; Lajolo, C.; Serpico, R.; Cecchetti, F.; Petruzzi, M. Correlation between Oral Lichen Planus and Viral Infections Other Than HCV: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5487.

- Donnarumma, G.; de Gregorio, V.; Fusco, A.; Farina, E.; Baroni, A.; Esposito, V.; Contaldo, M.; Petruzzi, M.; Pannone, G.; Serpico, R. Inhibition of HSV-1 Replication by Laser Diode-Irradiation: Possible Mechanism of Action. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2010, 23, 1167–1176.

- Lucchese, A.; Serpico, R.; Crincoli, V.; Shoenfeld, Y.; Kanduc, D. Sequence Uniqueness as a Molecular Signature of HIV-1-Derived B-Cell Epitopes. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2009, 22, 639–646.

- Kanduc, D.; Serpico, R.; Lucchese, A.; Shoenfeld, Y. Correlating Low-Similarity Peptide Sequences and HIV B-Cell Epitopes. Autoimmun. Rev. 2008, 7, 291–296.

- Constantin, M.; Chifiriuc, M.C.; Mihaescu, G.; Vrancianu, C.O.; Dobre, E.G.; Cristian, R.E.; Bleotu, C.; Bertesteanu, S.V.; Grigore, R.; Serban, B.; et al. Implications of oral dysbiosis and HPV infection in head and neck cancer: From molecular and cellular mechanisms to early diagnosis and therapy. Front. Oncol. 2023, 13, 1273516.

- Romano, A.; di Stasio, D.; Lauritano, D.; Lajolo, C.; Fiori, F.; Gentile, E.; Lucchese, A. Topical Photodynamic Therapy in the Treatment of Benign Oral Mucosal Lesions: A Systematic Review. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2021, 50, 639–648.

- Boccellino, M.; di Stasio, D.; Romano, A.; Petruzzi, M.; Lucchese, A.; Serpico, R.; Frati, L.; di Domenico, M. Lichen Planus: Molecular Pathway and Clinical Implications in Oral Disorders. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2018, 32 (Suppl. S1), 135–138.

- della Vella, F.; Lauritano, D.; Lajolo, C.; Lucchese, A.; di Stasio, D.; Contaldo, M.; Serpico, R.; Petruzzi, M. The Pseudolesions of the Oral Mucosa: Differential Diagnosis and Related Systemic Conditions. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2412.

- Romano, A.; di Stasio, D.; Petruzzi, M.; Fiori, F.; Lajolo, C.; Santarelli, A.; Lucchese, A.; Serpico, R.; Contaldo, M. Noninvasive Imaging Methods to Improve the Diagnosis of Oral Carcinoma and Its Precursors: State of the Art and Proposal of a Three-Step Diagnostic Process. Cancers 2021, 13, 2864.

- di Stasio, D.; Romano, A.; Paparella, R.S.; Gentile, C.; Serpico, R.; Minervini, G.; Candotto, V.; Laino, L. How Social Media Meet Patients’ Questions: YouTube™ Review for Mouth Sores in Children. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2018, 32 (Suppl. S1), 117–121.

- Gioco, G.; Rupe, C.; Basco, A.; Contaldo, M.; Gallenzi, P.; Lajolo, C. Oral Juvenile Xanthogranuloma: An Unusual Presentation in an Adult Patient and a Systematic Analysis of Published Cases. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2022, 133, 42–49.

- Minervini, G.; Romano, A.; Petruzzi, M.; Maio, C.; Serpico, R.; di Stasio, D.; Lucchese, A. Oral-Facial-Digital Syndrome (OFD): 31-Year Follow-up Management and Monitoring. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2018, 32 (Suppl. S1), 127–130.

- Romano, A.; Santarelli, A.; Lajolo, C.; della Vella, F.; Mascitti, M.; Serpico, R.; Contaldo, M. Analysis of Oral Mucosa Erosive-Ulcerative Lesions by Reflectance Confocal Microscopy. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2019, 33 (Suppl. S1), 11–17.

- de Benedittis, M.; Petruzzi, M.; Favia, G.; Serpico, R. Oro-Dental Manifestations in Hallopeau-Siemens-Type Recessive Dystrophic Epidermolysis Bullosa. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2004, 29, 128–132.

- Angelini, G.; Bonamonte, D.; Lucchese, A.; Favia, G.; Serpico, R.; Mittelman, A.; Simone, S.; Sinha, A.A.; Kanduc, D. Preliminary Data on Pemphigus Vulgaris Treatment by a Proteomics-Defined Peptide: A Case Report. J. Transl. Med. 2006, 4, 43.

- Lucchese, A.; Mittelman, A.; Tessitore, L.; Serpico, R.; Sinha, A.A.; Kanduc, D. Proteomic Definition of a Desmoglein Linear Determinant Common to Pemphigus Vulgaris and Pemphigus Foliaceous. J. Transl. Med. 2006, 4, 37.

- di Stasio, D. An Overview of Burning Mouth Syndrome. Front. Biosci. 2016, 8, 762.

- Mussap, M.; Beretta, P.; Esposito, E.; Fanos, V. Once upon a Time Oral Microbiota: A Cinderella or a Protagonist in Autism Spectrum Disorder? Metabolites 2023, 13, 1183.

- Mascitti, M.; Togni, L.; Caponio, V.C.A.; Zhurakivska, K.; Bizzoca, M.E.; Contaldo, M.; Serpico, R.; lo Muzio, L.; Santarelli, A. Lymphovascular Invasion as a Prognostic Tool for Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 51, 1–9.

- Romano, A.; di Stasio, D.; Gentile, E.; Petruzzi, M.; Serpico, R.; Lucchese, A. The Potential Role of Photodynamic Therapy in Oral Premalignant and Malignant Lesions: A Systematic Review. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2021, 50, 333–344.

- di Stasio, D.; Romano, A.; Russo, D.; Fiori, F.; Laino, L.; Caponio, V.C.A.; Troiano, G.; Lo Muzio, L.; Serpico, R.; Lucchese, A. Photodynamic Therapy Using Topical Toluidine Blue for the Treatment of Oral Leukoplakia: A Prospective Case Series. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2020, 31, 101888.

- Mello, F.W.; Miguel, A.F.P.; Dutra, K.L.; Porporatti, A.L.; Warnakulasuriya, S.; Guerra, E.N.S.; Rivero, E.R.C. Prevalence of Oral Potentially Malignant Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2018, 47, 633–640.

- Villa, A.; Sonis, S. Oral Leukoplakia Remains a Challenging Condition. Oral Dis. 2018, 24, 179–183.

- Warnakulasuriya, S.; Johnson, N.W.; Van der Waal, I. Nomenclature and Classification of Potentially Malignant Disorders of the Oral Mucosa. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2007, 36, 575–580.

- van der Waal, I. Potentially Malignant Disorders of the Oral and Oropharyngeal Mucosa; Present Concepts of Management. Oral Oncol. 2010, 46, 423–425.

- di Stasio, D.; Romano, A.; Gentile, C.; Maio, C.; Lucchese, A.; Serpico, R.; Paparella, R.; Minervini, G.; Candotto, V.; Laino, L. Systemic and Topical Photodynamic Therapy (PDT) on Oral Mucosa Lesions: An Overview. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2018, 32 (Suppl. S1), 123–126.

- Hazarey, V.; Desai, K.M.; Warnakulasuriya, S. Proliferative verrucous leukoplakia/multifocal leukoplakia in patients with and without oral submucous fibrosis. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 2024, 29, e119–e127.

- Villa, A.; Woo, S.b. Leukoplakia—A Diagnostic and Management Algorithm. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 75, 723–734.

- Lan, Q.; Zhang, C.; Hua, H.; Hu, X. Compositional and functional changes in the salivary microbiota related to oral leukoplakia and oral squamous cell carcinoma: A case control study. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 1021.

- Evren, I.; Najim, A.M.; Poell, J.B.; Brouns, E.R.; Wils, L.J.; Peferoen, L.A.N.; Brakenhoff, R.H.; Bloemena, E.; van der Meij, E.H.; de Visscher, J.G.A.M. The value of regular follow-up of oral leukoplakia for early detection of malignant transformation. Oral Dis. 2023. Epub ahead of print.

- Holmstrup, P. Oral Erythroplakia-What Is It? Oral Dis. 2018, 24, 138–143.

- Fiori, F.; Rullo, R.; Contaldo, M.; Inchingolo, F.; Romano, A. Noninvasive In-Vivo Imaging of Oral Mucosa: State-of-the-Art. Minerva Dent. Oral Sci. 2021, 70, 286–293.

- Romano, A.; Contaldo, M.; della Vella, F.; Russo, D.; Lajolo, C.; Serpico, R.; di Stasio, D. Topical Toluidine Blue-Mediated Photodynamic Therapy for the Treatment of Oral Lichen Planus. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2019, 33 (Suppl. S1), 27–33.

- di Stasio, D.; Lucchese, A.; Romano, A.; Adinolfi, L.E.; Serpico, R.; Marrone, A. The Clinical Impact of Direct-Acting Antiviral Treatment on Patients Affected by Hepatitis C Virus-Related Oral Lichen Planus: A Cohort Study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 5409–5417.

- Romano, A.; Grassi, R.; Fiori, F.; Nardi, G.M.; Borgia, R.; Contaldo, M.; Serpico, R.; Petruzzi, M. Oral Lichen Planus and Epstein-Barr Virus: A Narrative Review. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2022, 36, 87–92.

- Romano, A.; Santoro, R.; Fiori, F.; Contaldo, M.; Serpico, R.; Lucchese, A. Image Postproduction Analysis as a Tool for Evaluating Topical Photodynamic Therapy in the Treatment of Oral Lichen Planus. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2022, 39, 102868.

- Iocca, O.; Copelli, C.; Rubattino, S.; Sedran, L.; Di Maio, P.; Arduino, P.G.; Ramieri, G.; Garzino-Demo, P. Oral cavity carcinoma in patients with and without a history of lichen planus: A comparative analysis. Head Neck 2023, 45, 1367–1375.

- Contaldo, M.; di Stasio, D.; Petruzzi, M.; Serpico, R.; Lucchese, A. In Vivo Reflectance Confocal Microscopy of Oral Lichen Planus. Int. J. Dermatol. 2019, 58, 940–945.

- Agha-Hosseini, F.; Sheykhbahaei, N.; SadrZadeh-Afshar, M.S. Evaluation of Potential Risk Factors that contribute to Malignant Transformation of Oral Lichen Planus: A Literature Review. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2016, 17, 692–701.

- Arakeri, G.; Patil, S.G.; Aljabab, A.S.; Lin, K.-C.; Merkx, M.A.W.; Gao, S.; Brennan, P.A. Oral Submucous Fibrosis: An Update on Pathophysiology of Malignant Transformation. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2017, 46, 413–417.

- Phulari, R.G.S.; Dave, E.J. A Systematic Review on the Mechanisms of Malignant Transformation of Oral Submucous Fibrosis. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2020, 29, 470–473.

- Hande, A.; Chaudhary, M.; Gawande, M.; Gadbail, A.; Zade, P.; Bajaj, S.; Patil, S.; Tekade, S. Oral Submucous Fibrosis: An Enigmatic Morpho-Insight. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2019, 15, 463.

- Chaturvedi, P.; Vaishampayan, S.S.; Nair, S.; Nair, D.; Agarwal, J.P.; Kane, S.V.; Pawar, P.; Datta, S. Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Arising in Background of Oral Submucous Fibrosis: A Clinicopathologically Distinct Disease. Head Neck 2012, 35, 1404–1409.

- Chaturvedi, P.; Malik, A.; Nair, D.; Nair, S.; Mishra, A.; Garg, A.; Vaishampayan, S. Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Associated with Oral Submucous Fibrosis Have Better Oncologic Outcome than Those Without. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2017, 124, 225–230.

- Balcere, A.; Konrāde-Jilmaza, L.; Pauliņa, L.A.; Čēma, I.; Krūmiņa, A. Clinical Characteristics of Actinic Keratosis Associated with the Risk of Progression to Invasive Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5899.

- EI-Naggar, A.K.; Chan, J.K.C.; Grandis, J.R.; Takata, T.; Slootweg, P.J. WHO Classification of Head and Neck Tumours; IARC: Lyon, France, 2017.

- Imanguli, M.; Alevizos, I.; Brown, R.; Pavletic, S.; Atkinson, J. Oral Graft-versus-Host Disease. Oral Dis. 2008, 14, 396–412.

- Pannone, G.; Bufo, P.; Santoro, A.; Franco, R.; Aquino, G.; Longo, F.; Botti, G.; Serpico, R.; Cafarelli, B.; Abbruzzese, A.; et al. WNT Pathway in Oral Cancer: Epigenetic Inactivation of WNT-Inhibitors. Oncol. Rep. 2010, 24, 1035–1041.

- Pannone, G.; Santoro, A.; Feola, A.; Bufo, P.; Papagerakis, P.; lo Muzio, L.; Staibano, S.; Ionna, F.; Longo, F.; Franco, R.; et al. The Role of E-Cadherin down-Regulation in Oral Cancer: CDH1 Gene Expression and Epigenetic Blockage. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 2014, 14, 115–127.

- Solomon, M.C.; Chandrashekar, C.; Kulkarni, S.; Shetty, N.; Pandey, A. Exosomes: Mediators of cellular communication in potentially malignant oral lesions and head and neck cancers. F1000Res 2023, 12, 58.

- Wetzel, S.L.; Wollenberg, J. Oral Potentially Malignant Disorders. Dent. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 64, 25–37.

- Caudell, J.J.; Gillison, M.L.; Maghami, E.; Spencer, S.; Pfister, D.G.; Adkins, D.; Birkeland, A.C.; Brizel, D.M.; Busse, P.M.; Cmelak, A.J.; et al. NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Head and Neck Cancers, Version 1.2022. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2022, 20, 224–234.

- Lajolo, C.; Patini, R.; Limongelli, L.; Favia, G.; Tempesta, A.; Contaldo, M.; de Corso, E.; Giuliani, M. Brown Tumors of the Oral Cavity: Presentation of 4 New Cases and a Systematic Literature Review. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2020, 129, 575–584.e4.

- Favia, G.; lo Muzio, L.; Serpico, R.; Maiorano, E. Angiosarcoma of the Head and Neck with Intra-Oral Presentation. A Clinico-Pathological Study of Four Cases. Oral Oncol. 2002, 38, 757–762.

- Favia, G.; Lo Muzio, L.; Serpico, R.; Maiorano, E. Rhabdomyoma of the Head and Neck: Clinicopathologic Features of Two Cases. Head Neck 2003, 25, 700–704.

- Lauritano, D.; Lucchese, A.; Contaldo, M.; Serpico, R.; lo Muzio, L.; Biolcati, F.; Carinci, F. Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Diagnostic Markers and Prognostic Indicators. J. Biol. Regul. Homeost. Agents 2016, 30 (Suppl. S1), 169–176.

- Rivera, C. Essentials of Oral Cancer. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 11884–11894.

- lo Muzio, L.; Leonardi, R.; Mariggiò, M.A.; Mignogna, M.D.; Rubini, C.; Vinella, A.; Pannone, G.; Giannetti, L.; Serpico, R.; Testa, N.F.; et al. HSP 27 as Possible Prognostic Factor in Patients with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Histol. Histopathol. 2004, 19, 119–128.

- lo Muzio, L.; Campisi, G.; Farina, A.; Rubini, C.; Pannone, G.; Serpico, R.; Laino, G.; de Lillo, A.; Carinci, F. P-Cadherin Expression and Survival Rate in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: An Immunohistochemical Study. BMC Cancer 2005, 5, 63.

- Lo Muzio, L.; Leonardi, R.; Mignogna, M.D.; Pannone, G.; Rubini, C.; Pieramici, T.; Trevisiol, L.; Ferrari, F.; Serpico, R.; Testa, N.; et al. Scatter Factor Receptor (c-Met) as Possible Prognostic Factor in Patients with Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2004, 24, 1063–1069.

- Pannone, G.; Bufo, P.; Caiaffa, M.F.; Serpico, R.; Lanza, A.; Lo Muzio, L.; Rubini, C.; Staibano, S.; Petruzzi, M.; de Benedictis, M.; et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 Expression in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2004, 17, 273–282.

- Pannone, G.; Sanguedolce, F.; de Maria, S.; Farina, E.; Lo Muzio, L.; Serpico, R.; Emanuelli, M.; Rubini, C.; de Rosa, G.; Staibano, S.; et al. Cyclooxygenase Isozymes in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: A Real-Time RT-PCR Study with Clinic Pathological Correlations. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2007, 20, 317–324.

- Fiorelli, A.; Ricciardi, C.; Pannone, G.; Santoro, A.; Bufo, P.; Santini, M.; Serpico, R.; Rullo, R.; Pierantoni, G.M.; di Domenico, M. Interplay between Steroid Receptors and Neoplastic Progression in Sarcoma Tumors. J. Cell Physiol. 2011, 226, 2997–3003.

- Aquino, G.; Pannone, G.; Santoro, A.; Liguori, G.; Franco, R.; Serpico, R.; Florio, G.; de Rosa, A.; Mattoni, M.; Cozza, V.; et al. PEGFR-Tyr 845 Expression as Prognostic Factors in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2012, 13, 967–977.

- Saikia, P.J.; Pathak, L.; Mitra, S.; Das, B. The emerging role of oral microbiota in oral cancer initiation, progression and stemness. Front. Immunol. 2023, 14, 1198269.

- di Spirito, F.; Amato, A.; Romano, A.; Dipalma, G.; Xhajanka, E.; Baroni, A.; Serpico, R.; Inchingolo, F.; Contaldo, M. Analysis of Risk Factors of Oral Cancer and Periodontitis from a Sex- and Gender-Related Perspective: Gender Dentistry. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9135.

- Pannone, G.; Santoro, A.; Carinci, F.; Bufo, P.; Papagerakis, S.M.; Rubini, C.; Campisi, G.; Giovannelli, L.; Contaldo, M.; Serpico, R.; et al. Double Demonstration of Oncogenic High Risk Human Papilloma Virus DNA and HPV-E7 Protein in Oral Cancers. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2011, 24 (Suppl. S2), 95–101.

- Favia, G.; Kanduc, D.; lo Muzio, L.; Lucchese, A.; Serpico, R. Possible Association between HPV16 E7 Protein Level and Cytokeratin 19. Int. J. Cancer 2004, 111, 795–797.

- Kanduc, D.; Lucchese, A.; Mittelman, A. Individuation of Monoclonal Anti-HPV16 E7 Antibody Linear Peptide Epitope by Computational Biology. Peptides 2001, 22, 1981–1985.

- Katirachi, S.K.; Grønlund, M.P.; Jakobsen, K.K.; Grønhøj, C.; von Buchwald, C. The Prevalence of HPV in Oral Cavity Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Viruses 2023, 15, 451.

- Mao, L. Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma–Progresses from Risk Assessment to Treatment. Chin. J. Dent. Res. 2012, 15, 83–88.

- Contaldo, M.; Di Napoli, A.; Pannone, G.; Franco, R.; Ionna, F.; Feola, A.; De Rosa, A.; Santoro, A.; Sbordone, C.; Longo, F.; et al. Prognostic Implications of Node Metastatic Features in OSCC: A Retrospective Study on 121 Neck Dissections. Oncol. Rep. 2013, 30, 2697–2704.

- Johnson, D.E.; Burtness, B.; Leemans, C.R.; Lui, V.W.Y.; Bauman, J.E.; Grandis, J.R. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2020, 6, 92, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2023, 9, 4.

- de Maria, S.; Pannone, G.; Bufo, P.; Santoro, A.; Serpico, R.; Metafora, S.; Rubini, C.; Pasquali, D.; Papagerakis, S.M.; Staibano, S.; et al. Survivin Gene-Expression and Splicing Isoforms in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 135, 107–116.

- Pannone, G.; Hindi, S.A.H.; Santoro, A.; Sanguedolce, F.; Rubini, C.; Cincione, R.I.; de Maria, S.; Tortorella, S.; Rocchetti, R.; Cagiano, S.; et al. Aurora B Expression as a Prognostic Indicator and Possible Therapeutic Target in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2011, 24, 79–88.

- lo Muzio, L.; Mignogna, M.; Pannone, G.; Rubini, C.; Grassi, R.; Nocini, P.; Ferrari, F.; Serpico, R.; Favia, G.; de Rosa, G.; et al. Expression of Bcl-2 in Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma: An Immunohistochemical Study of 90 Cases with Clinico-Pathological Correlations. Oncol. Rep. 2003, 10, 285–291.

- Wehrhan, F.; Büttner-Herold, M.; Hyckel, P.; Moebius, P.; Preidl, R.; Distel, L.; Ries, J.; Amann, K.; Schmitt, C.; Neukam, F.W.; et al. Increased Malignancy of Oral Squamous Cell Carcinomas (Oscc) Is Associated with Macrophage Polarization in Regional Lymph Nodes—An Immunohistochemical Study. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 522.

- Zanoni, D.K.; Montero, P.H.; Migliacci, J.C.; Shah, J.P.; Wong, R.J.; Ganly, I.; Patel, S.G. Survival Outcomes after Treatment of Cancer of the Oral Cavity (1985–2015). Oral Oncol. 2019, 90, 115–121.

- Somma, P.; lo Muzio, L.; Mansueto, G.; Delfino, M.; Fabbrocini, G.; Mascolo, M.; Mignogna, C.; di Benedetto, M.; Carinci, F.; de Lillo, A.; et al. Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Lower LIP: Fas/Fasl Expression, Lymphocyte Subtypes and Outcome. Int. J. Immunopathol. Pharmacol. 2005, 18, 59–64.

- Mittelman, A.; Lucchese, A.; Sinha, A.A.; Kanduc, D. Monoclonal and Polyclonal Humoral Immune Response to EC HER-2/NEU Peptides with Low Similarity to the Host’s Proteome. Int. J. Cancer 2002, 98, 741–747.

- Staibano, S.; lo Muzio, L.; Pannone, G.; Somma, P.; Farronato, G.; Franco, R.; Bambini, F.; Serpico, R.; de Rosa, G. P53 and HMSH2 Expression in Basal Cell Carcinomas and Malignant Melanomas from Photoexposed Areas of Head and Neck Region. Int. J. Oncol. 2001, 19, 551–559.

- López-Jornet, P.; Olmo-Monedero, A.; Peres-Rubio, C.; Pons-Fuster, E.; Tvarijonaviciute, A. Preliminary Evaluation Salivary Biomarkers in Patients with Oral Potentially Malignant Disorders (OPMD): A Case-Control Study. Cancers 2023, 15, 5256.