Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

The transition to sustainable energy sources presents significant challenges for energy distribution and consumption systems. Specifically, the intermittent availability of renewable energy sources and the decreasing usage of fossil fuels pose challenges to energy flexibility and efficiency. An approach to tackle these challenges is demand-side management, aiming to adapt energy consumption and demand. A key requirement for demand-side management is the traceability of the energy flow among individual energy consumers.

- demand-side management

- barriers

- manufacturing systems

- industrial system

1. Introduction

The United Nations (UN) sustainable development goals (SDG) provide an aim towards a sustainable future for humanity [1]. In particular, the goal of SDG 13 is to take urgent action to combat climate change, and its impacts have gained traction in the last few years. Also, driven by international agreements like the Paris Agreement or the European Green deal, goals have been set to limit emitted greenhouse gases. Closely related to combating climate change is UN SDG 7 to “ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all”. In detail, the subgoals 7.1 to 7.3 state, until 2030, that universal access to reliable and modern energy services shall be granted, the share of renewable energy shall be increased substantially, and the rate of energy efficiency improvement shall be doubled [1]. Sustainable energy can be classified by technical, social, economical, environmental, and institutional dimensions, where the main sustainability goals can be summarized as energy efficiency, self-sufficiency, and low carbon intensity [2]. Thus, the clear need to utilize sustainable energy sourcing and consumption patterns surfaces.

A considerable share of energy is consumed by the industrial sector. Reports of the International Energy Agency (IEA) indicate that the industrial sector is responsible for approximately one third of energy demands and up to 45 percent of CO2 equivalent emissions [3]. To implement measures mitigating global warming until 2050, the IEA proposed several scenarios highlighting the need for energy transition. Three main synergetic strategies are proposed to close the gap with climate objectives, namely, expansion of renewable energy sources (RES), increase in energy efficiency (EE), and electrification of end uses. This is particularly driven by phasing out fossil fuels. In fact, the share of unabated fossil fuels will be less than 5% in 2050 compared with 2021’s share of 50% to reach net-zero emissions [3].

By being responsible for more than 40% of electricity consumption [4], industrial energy transition is a key factor towards a net-zero scenario. By analyzing the IEA’s net-zero energy scenario in detail, a notable detail is the different industrial sector strategies. While the strategy of the energy-intense industries, which by IEA definition comprises the steel, chemical and concrete industries, is mainly composed of alternative energy sources, e.g., hydrogen and technological advances such as carbon capture and storage, the less-energy-intense (light) industries have a different strategy, strongly aimed to increase electrification.

In combination with the rapidly increasing proportion of RES, which are mostly available intermittently, the need to have energy available at the right time surfaces. In addition to the intensively investigated approaches to energy storage technologies, however, there is also the possibility of adapting procedures and processes to the availability of energy. This results in an area of conflict between the possible additional costs of energy storage versus the financial and organizational expenditures of adaptability of procedures and processes to the energy availability.

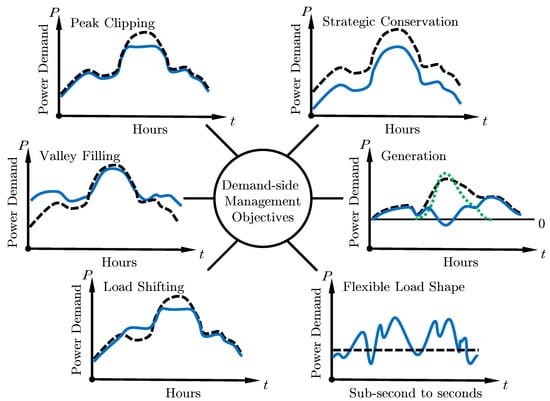

A concept with a long history to tackle the resulting conflict is ’demand-side management’ (DSM) which emerged around 1980 to tackle a perceived long-time shortage in the energy supply [5]. The concept was first mentioned by Gellings [6] and initially included (i) peak clipping, (ii) valley filling, (iii) load shifting, (iv) strategic conservation, (v) strategic load growth, and (vi) flexible load shape as objectives. Through the years, DSM evolved by technological innovations, but also adapted to the evolving energy markets’ pricing schemes. Nowadays, DSM is commonly used to refer to the combination of energy efficiency and energy flexible, i.e., demand-response actions [7].

Current applications of demand-side management are mostly driven by financial incentives and aim to (i) improve energy efficiency and the respective energy consumption cost, (ii) mitigate load peaks or fill valleys to reduce the provision fee for the electrical connection power, (iii) shift loads in accordance to flexible spot market pricing, (iv) flexibilize loads to participate in the reserve market to receive financial compensation and (v) use on-site generation to combine effects of peak clipping and strategic conservation of grid-supplied power. The modern interpretation of DSM objectives is visualized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Visual examples of modern demand-side management objectives.

Lund et al. [8] summarize the DSM benefits for system operators as a reduction in price peaks and the average spot price, shifting market power to consumers, postponing grid expansion, and reducing transmission and distribution losses. In combination with variable RES (VRES), DSM measures are able to achieve a 20% cost reduction, a 10% to 20% increase in VRES consumption, and a significantly reduced peak demand up to 50% [8]. A major barrier responsible for the slow adaption of DSM is the lack of information and communication technology (ICT) infrastructure, and the technological financing in combination with missing automation, as pointed out by Strbac [9] in 2008 and Kim and Shcherbakova [10] in 2011. With the ongoing roll-out of Industry 4.0 and similar concepts, the lack of ICT infrastructure is decreasing steadily and new methods to determine the DSM potentials arise. In fact, by being responsible for a major share of electricity consumption, light industry features a major potential to apply DSM in accordance with the high penetration of RES. To evaluate and apply the potentials of the wider availability of ICT hardware within the DSM objectives, a study is conducted to determine the energy consumption of industrial equipment, with the respective industrial peculiarities.

2. Demand-Side Management Barriers, Drivers, and Applications in the Industry

Due to its long history, DSM in the industrial sector has already been the subject of a number of studies considering the possible benefits. Multiple reviews point out the arising potentials to integrate the DSM objectives into industrial applications, by introducing operational data management. In order to operate an industrial demand-side managed plant, integrated communication systems and sensors, automated metering, and intelligent devices are necessary [7]. In 2021, Siddiquee et al. [11] identified information sharing as a key barrier for applied demand-response, which should be tackled by big data and data analytics to enable DR applications. Menghi et al. [12] analyzed energy efficiency barriers of manufacturing systems in 2019 and pointed out the opportunities introduced by Industry 4.0 and data management systems. In detail, most EE barriers are related to transparent data acquisition and structured data evaluation. In a review of energy-intense industries, Golmohamadi [13] also points out the availability of technical and market data as a key challenge to address to enable DSM applications.

A driver to overcome the data-related barriers are savings through various incentive programs. As VRES, e.g., wind power or photovoltaic power, feature the lowest levelized cost of energy, direct savings can be achieved by utilizing these sources, with the DSM objective of generation. There is a strong correlation between electricity prices and the availability of renewables [14]. Thus, with the rising share of VRES, a rising volatility of prices in the energy exchange markets is anticipated. The rising financial and greenhouse gas emission saving potentials are seen as the key driver towards industrial DSM. There are further saving potentials enabled by flattening the load curve with valley filling or peak shaving, as the charge for the electricity connection of industrial consumers is usually dependent on the quarter-hourly maximum load. In several scientific publications, the topics of DR and EE are considered without interdependencies. Contrary, more recent publications emphasize in particular the investment in energy efficiency measures, as this can result in the reduction of peak loads and demand-response synergies [15][16][17].

The actual possibilities are largely dependent on the flexibility of loads, i.e., not all energy consumers can be switched off or controlled. Loads can be distinguished as non-interruptible, schedulable, controllable, transferable, and energy storing [18], and possible measures are chosen appropriately. It is also possible to extend the scope of industrial consumers to the building services. Dababneh et al. [19] and Jin et al. [20] used the average, respectively rated power of machines as heating sources in the HVAC planning to reduce peak power demand. For the automotive manufacturing industry, Emec et al. [21] researched the load shift and process optimization potential, and concluded a 20% energy consumption and cost savings potential. Tristán et al. [22] researched the introduction of an energy management system for three industrial systems in combination with combined heat and power, as well as a photovoltaic array for energy flexible applications. The scientific SotA thus indicates the application potential for cross-cutting and complex application scenarios.

3. Formal Representation of Manufacturing Systems

In their review of energy efficiency barriers Mengi et al. [12] pointed out the possibilities of data acquisition and furthermore stressed the complexity of production environments for data analysis. Thus, a structured procedure is necessary to map a physical manufacturing system formally. While conventional methods organized the data flow over several levels, namely field level, control level, supervisory level, planning, and management level, modern methods, e.g., the Industry 4.0 paradigm, use a node-based structure. While a node-based structure is able to depict complex flows, it may become congested and not able to visualize a system’s hierarchy properly. Thus, within a modern industrial environment, a system’s hierarchy and data flow have to be separated.

For the energy focus within DSM applications, an alternative representation can also be based on the energy flow. Fundamental works are based on the energetic input–output analysis by Bullard and Herendeen [23] and the embodied energy paradigm formalized by Costanza [24]. The embodied energy paradigm was adapted for a general industrial context by Rahimifard [25] and traces the energy consumption of processes to the manufacturing of goods and services. While the concept has a long history, it is still used in research and practical applications [26]. The embodied energy flow shows a structured possibility to trace energy flows over various hierarchical levels and allocate the consumption in products.

The actual process levels’ common modeling paradigm utilizes exergy principles [27] or systems engineering paradigms. Individual processes are then concisely identified by their singular inputs in the form of material and energy, and, conversely, their outputs as waste heat and products [27]. Anchored around the unit processes, Duflou et al. [28] propose a concept that aims to increase the efficiency of both energy utilization and resource management within manufacturing through the implementation of a five-level hierarchy. This hierarchy includes the device/unit process, the line/cell/multi-machine system, the plant, the multi-plant system, and the enterprise/supply chain. The unit process interfaces distinguish between inputs and outputs for various materials, energy types, and emissions.

For DR applications, dos Santos et al. [18] differentiated industrial applications on the levels’ unit process, multi-machine, and factory level. Wiendahl et al. [29] acknowledges differentiating views for changeable manufacturing, highlighting the process level as common ground for all activities. For the integration of simulation models of cyber-physical production systems from various engineering domains into meta-models, Merschak et al. [30] suggest the levels’ components, modules, systems, factories, and cyber-physical production systems.

In a systems-based formalization, energy consumers such as machines are typically represented as individual systems. Within this representation, systems are represented as a block with internal properties, containing material, energy, and information as inputs and outputs [31]. Each system can feature subsystems, which also feature the respective in- and outputs. The representation is primarily focused towards the design of mechatronic systems and thus features a static hierarchy. For operational purposes, the formal model needs to constitute also dynamic information, material, and energy transfers. For example, a measurement device may be connected to different machines, a situation that cannot be represented with static flows.

The scientific SotA thus does not agree on a standardized representation of industrial systems. While there are multiple variants to visualize an industrial system, the actual depiction depends on the use case. Modern manufacturing systems require a graph-based depiction to be represented properly.

4. Process Load Modeling and Estimation

In the field of energy-related process load modeling and estimation techniques for manufacturing systems, various scientific efforts have been made to identify and improve prediction approaches. Schmidt et al. [32] delved into the predictive methods related to assets in the manufacturing industry, specifically highlighting the limitations of Gutowski’s approach, noting that, although it was applied to various manufacturing processes, the lack of coefficients hindered its direct use in predicting energy consumption for specific machine tools. In addition, Schmidt et al. [32] categorized machine types by complexity as simple, adjustable, single-purpose, and multi-purpose complex, and advocated the use of semi-empirical equations to model complex machines. The energy consumption monitoring patterns can be classified as constant consumption, controlled constant consumption, and variable consumption [33].

Garwood [34] highlighted different modeling methods for energy simulation tools in the manufacturing sector. Notable distinctions were made between time-driven, event-driven, continuous flow, numerical techniques, agent-driven, and co-simulation models.

Correlating with the detail of the model, the amount of data-driven varies, i.e., while most multi-machine applications, e.g., scheduling of jobs, use recorded values, unit level applications in the contrary, tend to be explainable. In fact, aside from state-based scheduling models, as introduced by Shrouf et al. [35], it is common to use the rated power or a measured average for multi-machine applications. Gong et al. [36] proposed a state-based model to elucidate the energy consumption at a machine level, specifically focusing on the power consumption of a grinding machine. Beier et al. [37] demonstrated real-time control using state-based models that rely on renewable energy sources and represent processes as discrete entities capable of switching between idle, production, and off states.

To compare the efficiencies of processes, energy key performance indicators (EnPIs) are needed. Yoon et al. [38] conducted an analysis of the specific energy consumption (SEC) as an EnPI in different manufacturing processes, and found interesting differences. The SEC is defined as energy consumption per production of one material unit, thus enabling comparisons between different manufacturing technologies. In particular, the specific energy consumption of additive processes was found to be about 100 times higher than that of bulk-forming processes. A key difference between a digital twin and a virtual testbed is the fully virtualized control [39]. Li et al. [40] introduced the concept of an energy digital twin based on a data-driven hybrid Petri net (DDPHN), and demonstrated its superiority over multiple data-driven models in simulating the energy consumption behavior of die casting. The DDPHPN reached a coefficient of determination up to 0.9662 for the needed power consumption of the casting process, demonstrating the feasibility of the data-driven methods.

In the machining domain, several publications have focused on estimating energy consumption. Liu et al. [41] proposed a model for the energy consumption of the machining process, featuring a validation error of 7.773% evaluating individual machine states, while Kara et al. [42] performed an estimation of machining energy consumption on turning and milling machines, reaching over 90% prediction accuracy. The work of Salonitis et al. [43] proposed machine disaggregation to explore energy efficiency potentials at the machine tool level by decomposing energy consumption into individual subsystems. Taken together, these efforts contribute to advancing the understanding and modeling of energy consumption in manufacturing processes.

Within the conducted literature survey, mostly white-box models, i.e., where all parameters for the calculation of the energy consumption are known, and black-box models, i.e., where the energy consumption of a system is calculated by purely data-driven methods, were applied. Grey-box models, on the contrary, which combine the existing knowledge of a system and apply data-driven methods, were not intensely studied on a process level for energy consumption estimation in industrial applications.

For other applications with grey-box models, multiple solutions exist. Fleschutz et al. [44] propose an energy optimization software framework for industrial applications on a system level, including multiple energy sources, energy storage systems and data-driven load analysis. Within the framework, multiple DR aspects can be optimized, including the peak load. Vanfretti et al. [45] introduced the RaPId toolbox to estimate FMI models for power and electric systems. ModestPy, an FMI-based python package, is a gray-box estimator, mainly applied in building services and HVAC systems [46]. For the model-predictive control of buildings, Drgona et al. [47] provide a thorough review and a unified framework, acknowledging the existing solutions and tools. Grosch et al. [48] propose an OpenAI-based framework to optimize factory operations energetically. A recent application of the parameter estimation method as an adaptive energy model was proposed by Bermeo-Ayerbe [49], and it outperformed artificial neural nets and autoregressive models with a maximum fit rate of approximately 82%, where other models had a rate less than 66%. Table 1 contains a selection of existing tools for parameter estimation of programmable objective functions, as well as simulation and data-driven models. To the best knowledge of the authors, none of the existing parameter estimation solutions evaluated contain the necessary data preparation for energy simulations on a process/unit level, suitable for the mutable nature of industrial applications.

Table 1. Selected solutions for parameter estimation.

| Solution | Language | Model Interface | Type | Active Development 1 | Free |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ModestPy [46] | Python | Functional Mockup Interface | Grey Box | no | yes |

| OMSysIdent | OpenModelica | OMSimulator models | Grey Box | yes | yes |

| Parameter Identification Toolbox | Matlab | Simulink models | Grey Box | yes | no |

| Pyomo [50] | Python | Pyomo Models (Python Functions) | Grey or Black Box | yes | yes |

| RaPId toolbox [45] | Matlab | Functional Mockup Interface | Grey Box | no | yes |

| SciPy | Python | Python Functions | Grey or Black Box | yes | yes |

| Stats Package | R | R functions | Grey or Black Box | yes | yes |

| SysIdentPy [51] | Python | NARMAX et al. | Black Box | yes | yes |

| SIPPY [52] | Python | ARX et al. | Black Box | yes | yes |

1 New version released or active development within the last 12 months.

5. Knowledge Gaps

The addressed scientific problem is the missing knowledge of applicability and potential of a consistent parameter estimation method for energy consumption considerations. Contrary to buildings, manufacturing entities, e.g., machines, can exhibit a significantly more complex system architecture and mostly include multiphysical phenomena. In detail, manufacturing entities feature a variety of information, energy, and material in- and outputs, which are subject to temporal changes of relations and can be comprised of subsystems, where the same characteristics apply.

The trends and developments in industrial ICT result in widespread data acquisition, while a key issue of industrial DSM is data availability. To counter the complexity of industrial systems, a holistic analysis is needed to retrieve meaningful insights from data processing [12]. In order to interpret the collected data, data-driven black-box applications, e.g., machine learning, become significantly more prevalent. Although the performance of these applications enables detailed predictions and insights, they come with the downside that they lack explainability and are often computationally expensive. White-box models, on the contrary, are poorly suited for most retrofitting applications, caused by the requirement to gather all the necessary detail information and parameters. Moreover, the considerable modeling effort to incorporate minor physical effects mostly exceeds the possible benefits for industrial applications in the operational phase. Thus, the gap in knowledge is identified as follows

-

The scientific SotA indicates no known approach to deal with the complexity and mutability of industrial systems for DSM applications, including consistent system modeling.

-

Although a variety of parameter estimation tools are known, there is no demonstrated use for the objectives of DSM. Furthermore, the potentials of identified parameters have not been evaluated within the context of industrial DSM.

By closing the gap between the missing data and appropriate evaluation, a variety of benefits are anticipated. In detail, the common energy sustainable goals would be assisted by provision of a tool to define, quantify, measure, and monitor EnPIs. Furthermore, with forecastable demands, VRES can be utilized to a higher degree to increase self-sufficiency and lower the carbon footprint.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/su16051995

References

- United Nations. Transforming the World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; Technical Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015.

- Iddrisu, I.; Bhattacharyya, S.C. Sustainable Energy Development Index: A Multi-Dimensional Indicator for Measuring Sustainable Energy Development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 50, 513–530.

- International Energy Agency. World Energy Outlook 2022; IEA: Paris, France, 2022.

- International Energy Agency. Key World Energy Statistics 2021; Technical Report; IEA: Paris, France, 2021.

- Loughran, D.S.; Kulick, J. Demand-Side Management and Energy Efficiency in the United States. Energy J. 2004, 25, 21–43.

- Gellings, C. The Concept of Demand-Side Management for Electric Utilities. Proc. IEEE 1985, 73, 1468–1470.

- Siano, P. Demand Response and Smart Grids—A Survey. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 30, 461–478.

- Lund, P.D.; Lindgren, J.; Mikkola, J.; Salpakari, J. Review of Energy System Flexibility Measures to Enable High Levels of Variable Renewable Electricity. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 45, 785–807.

- Strbac, G. Demand Side Management: Benefits and Challenges. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 4419–4426.

- Kim, J.H.; Shcherbakova, A. Common Failures of Demand Response. Energy 2011, 36, 873–880.

- Siddiquee, S.M.S.; Howard, B.; Bruton, K.; Brem, A.; O’Sullivan, D.T.J. Progress in Demand Response and It’s Industrial Applications. Front. Energy Res. 2021, 9, 673176.

- Menghi, R.; Papetti, A.; Germani, M.; Marconi, M. Energy Efficiency of Manufacturing Systems: A Review of Energy Assessment Methods and Tools. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 240, 118276.

- Golmohamadi, H. Demand-Side Flexibility in Power Systems: A Survey of Residential, Industrial, Commercial, and Agricultural Sectors. Sustainability 2022, 14, 7916.

- Suomalainen, K.; Pritchard, G.; Sharp, B.; Yuan, Z.; Zakeri, G. Correlation Analysis on Wind and Hydro Resources with Electricity Demand and Prices in New Zealand. Appl. Energy 2015, 137, 445–462.

- Dorahaki, S.; Rashidinejad, M.; Abdollahi, A.; Mollahassani-pour, M. A Novel Two-Stage Structure for Coordination of Energy Efficiency and Demand Response in the Smart Grid Environment. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2018, 97, 353–362.

- Wohlfarth, K.; Worrell, E.; Eichhammer, W. Energy Efficiency and Demand Response—Two Sides of the Same Coin? Energy Policy 2020, 137, 111070.

- Menniti, D.; Pinnarelli, A.; Sorrentino, N.; Stella, F.; Aura, C.; Liutic, C.; Polizzi, G. A Tool to Assess the Interaction between Energy Efficiency, Demand Response, and Power System Reliability. Energies 2022, 15, 5563.

- dos Santos, S.A.B.; Soares, J.M.; Barroso, G.C.; de Athayde Prata, B. Demand Response Application in Industrial Scenarios: A Systematic Mapping of Practical Implementation. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 215, 119393.

- Dababneh, F.; Li, L.; Sun, Z. Peak Power Demand Reduction for Combined Manufacturing and HVAC System Considering Heat Transfer Characteristics. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 177, 44–52.

- Jin, H.; Li, Z.; Sun, H.; Guo, Q.; Wang, B. Coordination on Industrial Load Control and Climate Control in Manufacturing Industry under TOU Prices. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2019, 10, 139–152.

- Emec, S.; Kuschke, M.; Chemnitz, M.; Strunz, K. Potential for Demand Side Management in Automotive Manufacturing. In Proceedings of the IEEE PES ISGT Europe 2013, Lyngby, Denmark, 6–9 October 2013; pp. 1–5.

- Tristán, A.; Heuberger, F.; Sauer, A. A Methodology to Systematically Identify and Characterize Energy Flexibility Measures in Industrial Systems. Energies 2020, 13, 5887.

- Bullard, C.W.; Herendeen, R.A. The Energy Cost of Goods and Services. Energy Policy 1975, 3, 268–278.

- Costanza, R. Embodied Energy and Economic Valuation. Science 1980, 210, 1219–1224.

- Rahimifard, S.; Seow, Y.; Childs, T. Minimising Embodied Product Energy to Support Energy Efficient Manufacturing. CIRP Ann. 2010, 59, 25–28.

- Xiong, W.; Huang, H.; Li, L.; Gan, L.; Zhu, L.; Gao, M.; Liu, Z. Embodied Energy of Parts in Sheet Metal Forming: Modeling and Application for Energy Saving in the Workshop. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 118, 3933–3948.

- Gutowski, T.; Dahmus, J.; Thiriez, A. Electrical Energy Requirements for Manufacturing Processes. In Proceedings of the 13th CIRP International Conference on Life Cycle Engineering, Leuven, Belgium, 31 May–2 June 2006.

- Duflou, J.R.; Sutherland, J.W.; Dornfeld, D.; Herrmann, C.; Jeswiet, J.; Kara, S.; Hauschild, M.; Kellens, K. Towards Energy and Resource Efficient Manufacturing: A Processes and Systems Approach. CIRP Ann. 2012, 61, 587–609.

- Wiendahl, H.P.; ElMaraghy, H.A.; Nyhuis, P.; Zäh, M.F.; Wiendahl, H.H.; Duffie, N.; Brieke, M. Changeable Manufacturing-Classification, Design and Operation. CIRP Ann. 2007, 56, 783–809.

- Merschak, S.; Hehenberger, P.; Witters, M.; Gadeyne, K. A Hierarchical Meta-Model for the Design of Cyber-Physical Production Systems. In Proceedings of the 2018 19th International Conference on Research and Education in Mechatronics (REM), Delft, The Netherlands, 6–7 June 2018; pp. 36–41.

- Hehenberger, P. Perspectives on Hierarchical Modeling in Mechatronic Design. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2014, 28, 188–197.

- Schmidt, C.; Li, W.; Thiede, S.; Kara, S.; Herrmann, C. A Methodology for Customized Prediction of Energy Consumption in Manufacturing Industries. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf.-Green Technol. 2015, 2, 163–172.

- Gontarz, A.M.; Hampl, D.; Weiss, L.; Wegener, K. Resource Consumption Monitoring in Manufacturing Environments. Procedia CIRP 2015, 26, 264–269.

- Garwood, T.L.; Hughes, B.R.; Oates, M.R.; O’Connor, D.; Hughes, R. A Review of Energy Simulation Tools for the Manufacturing Sector. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 895–911.

- Shrouf, F.; Ordieres-Meré, J.; García-Sánchez, A.; Ortega-Mier, M. Optimizing the Production Scheduling of a Single Machine to Minimize Total Energy Consumption Costs. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 67, 197–207.

- Gong, X.; De Pessemier, T.; Joseph, W.; Martens, L. A Generic Method for Energy-Efficient and Energy-Cost-Effective Production at the Unit Process Level. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 113, 508–522.

- Beier, J.; Thiede, S.; Herrmann, C. Energy Flexibility of Manufacturing Systems for Variable Renewable Energy Supply Integration: Real-time Control Method and Simulation. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 648–661.

- Yoon, H.S.; Lee, J.Y.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, M.S.; Kim, E.S.; Shin, Y.J.; Chu, W.S.; Ahn, S.H. A Comparison of Energy Consumption in Bulk Forming, Subtractive, and Additive Processes: Review and Case Study. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf.-Green Technol. 2014, 1, 261–279.

- Schluse, M.; Rossmann, J. From Simulation to Experimentable Digital Twins: Simulation-based Development and Operation of Complex Technical Systems. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Symposium on Systems Engineering (ISSE), Edinburgh, UK, 5 October 2016; pp. 1–6.

- Li, H.; Yang, D.; Cao, H.; Ge, W.; Chen, E.; Wen, X.; Li, C. Data-Driven Hybrid Petri-Net Based Energy Consumption Behaviour Modelling for Digital Twin of Energy-Efficient Manufacturing System. Energy 2022, 239, 122178.

- Liu, F.; Xie, J.; Liu, S. A Method for Predicting the Energy Consumption of the Main Driving System of a Machine Tool in a Machining Process. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 105, 171–177.

- Kara, S.; Li, W. Unit Process Energy Consumption Models for Material Removal Processes. CIRP Ann. 2011, 60, 37–40.

- Salonitis, K.; Ball, P. Energy Efficient Manufacturing from Machine Tools to Manufacturing Systems. Procedia CIRP 2013, 7, 634–639.

- Fleschutz, M.; Bohlayer, M.; Braun, M.; Murphy, M.D. Demand Response Analysis Framework (DRAF): An Open-Source Multi-Objective Decision Support Tool for Decarbonizing Local Multi-Energy Systems. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8025.

- Vanfretti, L.; Baudette, M.; Amazouz, A.; Bogodorova, T.; Rabuzin, T.; Lavenius, J.; Goméz-López, F.J. RaPId: A Modular and Extensible Toolbox for Parameter Estimation of Modelica and FMI Compliant Models. SoftwareX 2016, 5, 144–149.

- Arendt, K.; Jradi, M.; Wetter, M.; Veje, C.T. ModestPy: An Open-Source Python Tool for Parameter Estimation in Functional Mock-up Units. In Proceedings of the The American Modelica Conference, Cambridge, MA, USA, 9–10 October 2018; pp. 121–130.

- Drgoňa, J.; Arroyo, J.; Cupeiro Figueroa, I.; Blum, D.; Arendt, K.; Kim, D.; Ollé, E.P.; Oravec, J.; Wetter, M.; Vrabie, D.L.; et al. All You Need to Know about Model Predictive Control for Buildings. Annu. Rev. Control 2020, 50, 190–232.

- Grosch, B.; Ranzau, H.; Dietrich, B.; Kohne, T.; Fuhrländer-Völker, D.; Sossenheimer, J.; Lindner, M.; Weigold, M. A Framework for Researching Energy Optimization of Factory Operations. Energy Inform. 2022, 5, 29.

- Bermeo-Ayerbe, M.A.; Ocampo-Martinez, C.; Diaz-Rozo, J. Data-Driven Energy Prediction Modeling for Both Energy Efficiency and Maintenance in Smart Manufacturing Systems. Energy 2022, 238, 121691.

- Bynum, M.L.; Hackebeil, G.A.; Hart, W.E.; Laird, C.D.; Nicholson, B.L.; Siirola, J.D.; Watson, J.P.; Woodruff, D.L. Pyomo—Optimization Modeling in Python; Springer Optimization and Its Applications; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 67.

- Lacerda, W.R.; da Andrade, L.P.C.; Oliveira, S.C.P.; Martins, S.A.M. SysIdentPy: A Python Package for System Identification Using NARMAX Models. J. Open Source Softw. 2020, 5, 2384.

- Armenise, G.; Vaccari, M.; Di Capaci, R.B.; Pannocchia, G. An Open-Source System Identification Package for Multivariable Processes. In Proceedings of the 2018 UKACC 12th International Conference on Control (CONTROL), Sheffield, UK, 5–7 September 2018; pp. 152–157.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!