Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Helicobacter pylori is a class I carcinogen that infects more than 100 million individuals in the United States. Antimicrobial therapy for H. pylori has typically been prescribed empirically rather than based on susceptibility testing.

- clarithromycin

- antimicrobial stewardship

- Helicobacter pylori

1. Introduction

Helicobacter pylori infects approximately one-half of the world’s population and causes gastritis/gastric atrophy that may result in peptic ulcer disease and/or gastric cancer [1]. The problems of providing effective H. pylori therapy are not currently being embraced by the infectious disease community. For example, triple therapy that combines clarithromycin, amoxicillin, and an antisecretory drug called clarithromycin remains the most used regimen despite generally poor cure rates [2][3][4][5]. The regimen was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1996, at which time the FDA’s focus was on ulcer healing and recurrence rather than on the treatment of a new infectious disease [6][7][8]. Because the clinical manifestations were gastrointestinal and obtaining cultures required gastroscopy, this has led to the functional transfer of H. pylori from infectious disease to gastroenterology, which has managed the disease as any another common GI disease [9] and without employing the principles of antibiotic stewardship [10][11][12].

Antimicrobial resistance among H. pylori rapidly increased such that clarithromycin, nitroimidazoles, and fluoroquinolones are no longer effective when given empirically [13]. Nonetheless, clarithromycin-containing triple therapy remains the most widely used anti-H. pylori regimen worldwide [14][15]. Gastroenterology considered the unavailability of susceptibility testing as unsolvable, requiring “work arounds”. One approach was to add another antibiotic or antibiotics to current regimens to produce multi-antibiotic clarithromycin-containing regimens (e.g., sequential, hybrid, and concomitant therapies) (reviewed in [12]). The most successful regimen was concomitant therapy [16], which is equivalent to the simultaneous administration of clarithromycin and metronidazole triple therapies. Concomitant therapy failure requires resistance to both metronidazole and clarithromycin [17].

The FDA recently approved vonoprazan–clarithromycin–amoxicillin triple therapy in which more than 90% of patients receive clarithromycin unnecessarily [18]. Vonoprazan is a potassium-competitive acid blocker (P-CAB), more potent than traditional PPIs. The effectiveness of vonoprazan triple therapy is driven by the success of the dual P-CAB plus amoxicillin component [18][19].

2. Effect of Clarithromycin Resistance on Treatment Success

Clarithromycin resistance is considered “all or none”, such that clarithromycin resistance reduces clarithromycin triple therapy effectively to just amoxicillin and the antisecretory drug. This results in resistant infections receiving a PPI or P-CAB plus amoxicillin dual therapy and susceptible infections receiving PPI or P-CAB plus amoxicillin and clarithromycin. The results are visualized using an H. pylori nomogram (Figure 1) [20].

High H. pylori cure rates with amoxicillin require the antisecretory drug to achieve and sustain a high pH [21]. Effectiveness is thus positively related to the potency of the antisecretory drug and inversely correlated with the ability of the stomach to make acid. PPIs’ relative potency is assessed as the proportion of a 24-h day during which the pH is maintained at pH 4 or above (pH4 time) [22]. Pantoprazole, omeprazole, and lansoprazole are rapidly metabolized by CYP2C19, which reduces their effectiveness in populations where rapid metabolizers are common (e.g., most of the Western world). Rabeprazole and esomeprazole are the most potent PPIs and are minimally affected by CYP2C19. They are preferred PPIs for H. pylori therapy [23].

Amoxicillin dual therapy using traditional PPIs is unable to reliably cure a high proportion of cases in Western populations. In contrast, rabeprazole or esomeprazole dual therapies have often proved effective in Japan and in some Chinese populations [24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33].

3. Potassium-Competitive Acid Blockers (P-CABs)

The effectiveness of vonoprazan plus antibiotics for the treatment of H. pylori infections was first demonstrated in Japan [34]. The Japanese pivotal clinical study compared b.i.d dosing of a low potency PPI (lansoprazole 30 mg; equivalent to 27 mg omeprazole) [22] with 20 mg of vonoprazan (approximately equivalent to >40 mg of esomeprazole b.i.d.), each given b.i.d. for the cure of H. pylori infections [34]. With clarithromycin-susceptible infections, both the vonoprazan- and PPI-containing triple therapies produced high (~97%) and near-identical cure rates [34]. However, in the presence of clarithromycin resistance, the regimens were reduced to the antisecretory drug plus amoxicillin. The cure rates of the dual therapies were therefore dependent on the relative antisecretory potency of the antisecretory drug (i.e., the cure rate was 40% with lansoprazole vs. 82% with the more potent vonoprazan) [19]. The overall high cure rate obtained (82%) with clarithromycin resistance was consistent with the notion that clarithromycin was responsible for only a small proportion of those cured (i.e., 82% would have been cured without clarithromycin) [19]. It was also noted that the optimization of the vonoprazan–amoxicillin dual therapy should produce a highly effective dual therapy without the need for clarithromycin. However, vonoprazan triple therapy was introduced despite more than 80% receiving unneeded clarithromycin. Vonoprazan–clarithromycin triple therapy is currently the most widely used treatment of H. pylori in Japan with more than 1.5 million patients treated yearly [35]. However, over time, the overall cure rates have fallen closer to 80% as clarithromycin resistance has continued to increase [36]. In the U.S./European trial, the cure rates for both clarithromycin-susceptible and resistant strains were unacceptably low and the proportion receiving unneeded clarithromycin was higher (>90%) (see below) [37]. Despite the poor outcomes, both vonoprazan triple and dual therapies were approved in the United States and Europe, although neither has yet been released due to manufacturing issues.

4. Unnecessary Clarithromycin Resulting from Vonoprazan Triple Therapy

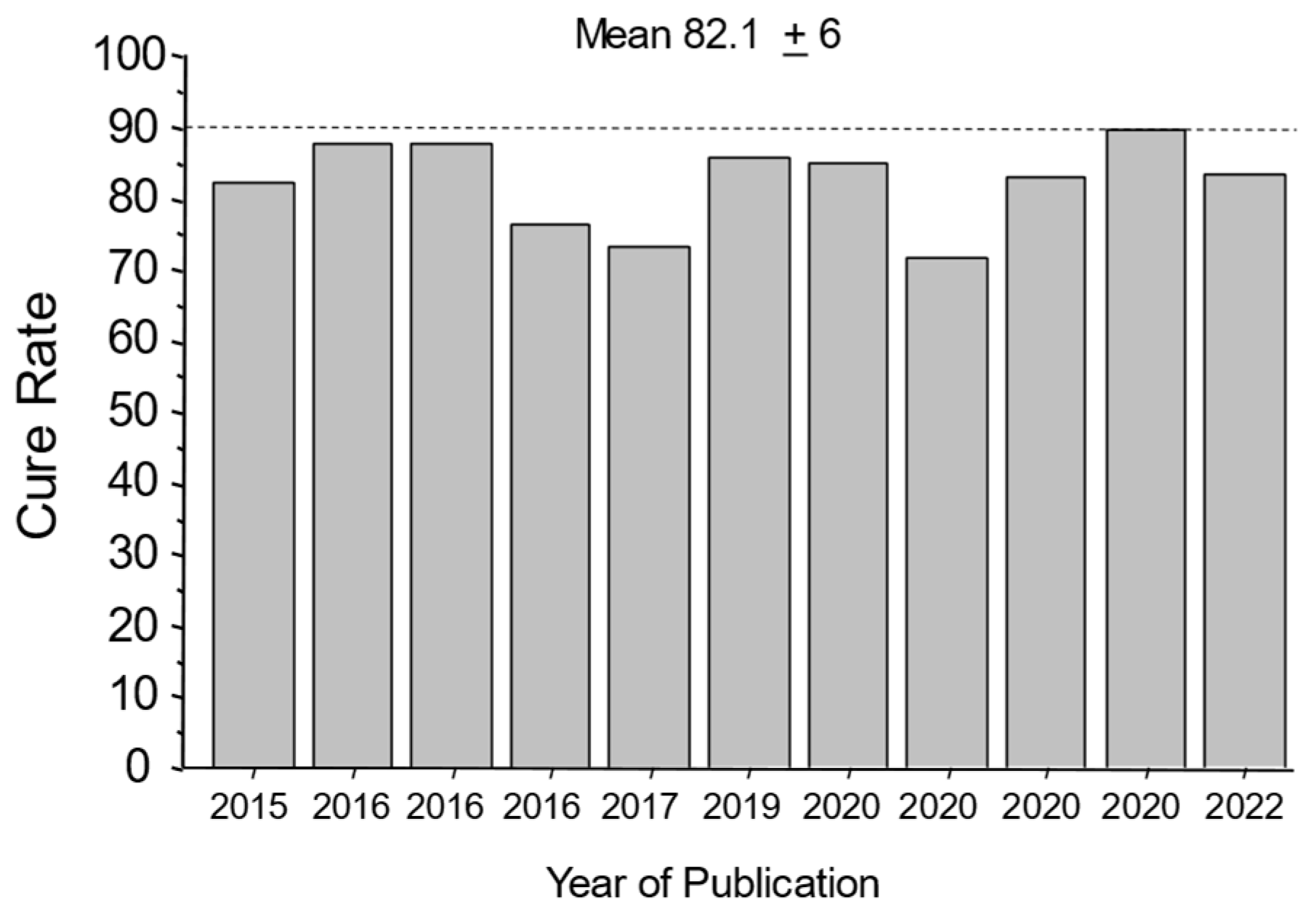

The results of the Japanese pivotal study (high success with the amoxicillin dual therapy and a high rate of unnecessary clarithromycin) have been confirmed by 11 vonoprazan triple therapy studies that provide cure rates in relation to clarithromycin resistance (i.e., the success is attributable to the amoxicillin) [34][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Cure rates with 7-day vonoprazan, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin therapy in the presence of clarithromycin-resistant infections in Japan. This illustrates the high proportion of patients cured while functionally receiving only the amoxicillin.

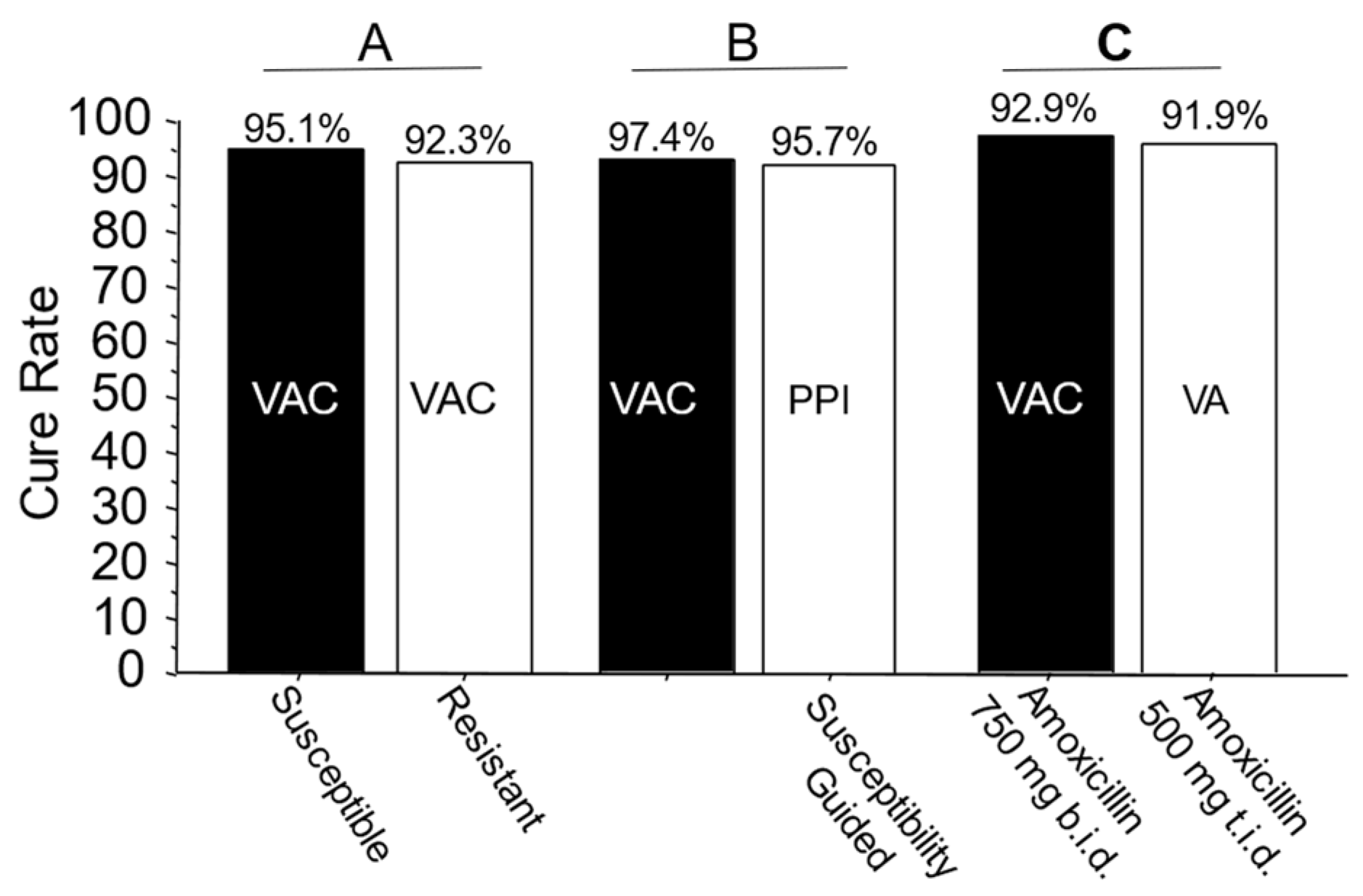

The mean cure rate attributable to amoxicillin dual therapy with a 7-day vonoprazan triple therapy was 81.7 ± 6% [34][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][49]. A second approach to quantitate the proportion receiving unnecessary clarithromycin was to examine the cure rates of dual therapy (which functionally contains no clarithromycin) vs. triple therapy with clarithromycin in the same populations (Figure 2A) [48]. These different comparisons all confirmed that the majority of the clarithromycin given in vonoprazan triple therapy was unneeded.

Figure 2. Examples of comparative studies in Japan. Legend: Panel A: Cure rates of 7-day vonoprazan, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin therapy in clarithromycin-susceptible and resistant infections in Japan. The resistant infections are functionally seen in vonoprazan and amoxicillin dual therapy. Panel B: Comparison of the effectiveness of vonoprazan–clarithromycin triple therapy vs. susceptibility-based PPI clarithromycin triple therapy in the same population. Panel C: Comparison of 7-day vonoprazan triple and dual therapy in the same population. In the triple therapy, 1500 mg of amoxicillin was given as 750 b.i.d. vs. 500 mg t.i.d. in the dual therapy. VAC—vonoprazan, amoxicillin, clarithromycin; PPI AC—PPI, amoxicillin, clarithromycin; VA—vonoprazan, amoxicillin. Vonoprazan was 20 mg b.i.d., clarithromycin was 200 mg b.i.d., amoxicillin was 750 mg b.i.d. except where shown.

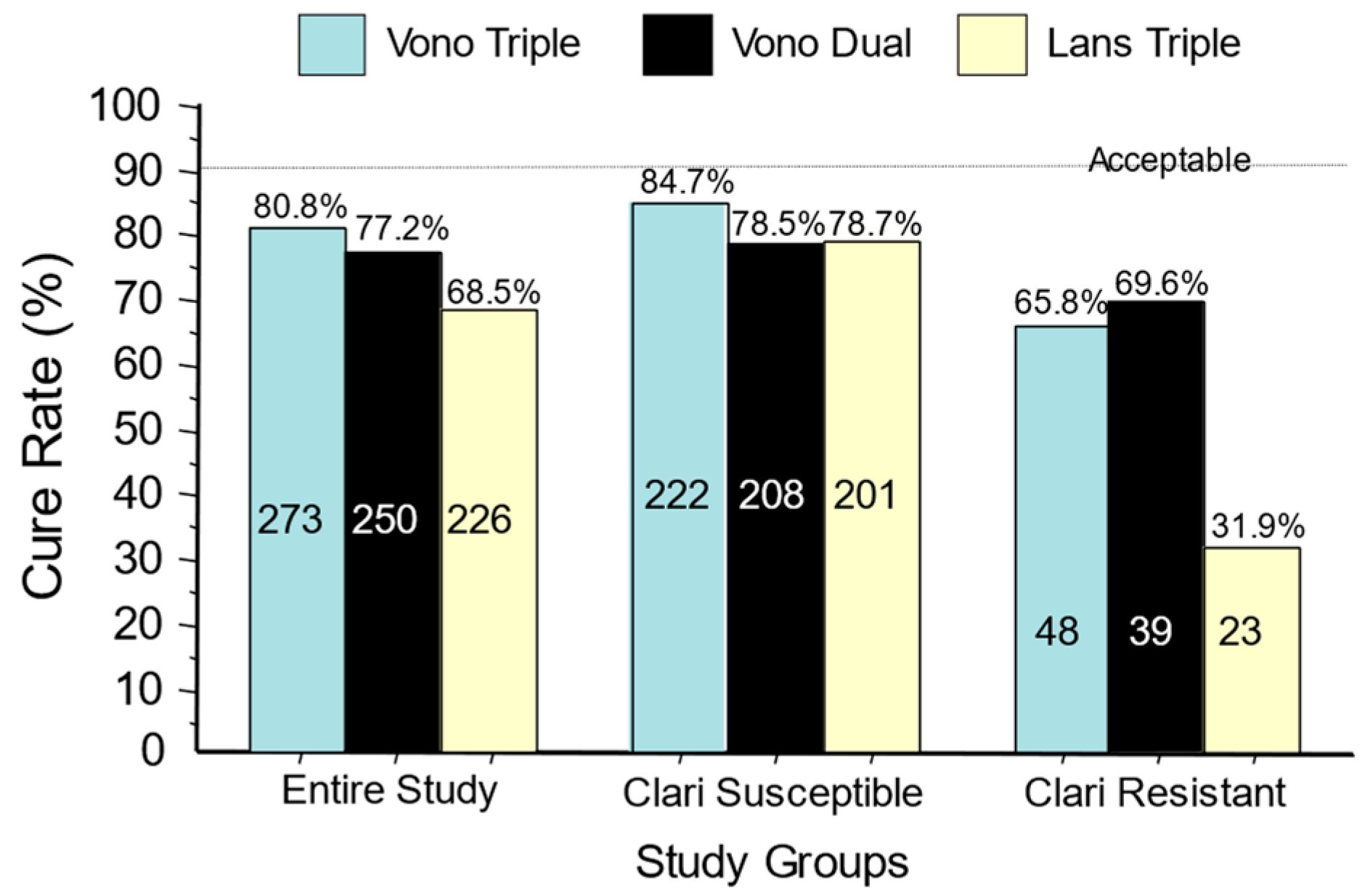

The U.S./European vonoprazan–amoxicillin–clarithromycin clinical trial differed from the Japanese trials in dosing, duration, and effectiveness. Despite higher doses of antibiotics and doubling the duration from 7 to 14 days, both the U.S./European study and a study in Thailand yielded relatively poor cure rates compared to Japan, even with susceptible strains (e.g., 85.7% with the P-CAB) [37][50]. This was both unexpected and unprecedented [18][51] (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Cure rates for the U.S./European vonoprazan clinical trial of vonoprazan, clarithromycin, and amoxicillin; vonoprazan plus amoxicillin dual therapy; and lansoprazole–clarithromycin triple therapy. The data are shown for the entire group and separately for those with clarithromycin-susceptible infections and those with clarithromycin-resistant infections. No arm achieved the expected cure rate of >90%.

The cure rate with susceptible strains using amoxicillin b.i.d. was 6.2% greater than dual therapy with amoxicillin t.i.d. The proportion receiving unnecessary clarithromycin was also evaluated both in relation to the differences in cure rates with susceptible vs. resistant infections and with dual vs. triple therapies (Figure 3 and Figure 4) [18].

Figure 4. Results of the U.S./European vonoprazan clinical trial graphical abstract, limited to the comparison of the vonoprazan triple and dual arms. Modification consisted of subtraction of the results with vonoprazan dual therapy from the results with triple therapy to show the relative benefits of adding clarithromycin. The vonoprazan dual therapy contained 3 g of amoxicillin vs. 2 g for the triple therapy, which also contained clarithromycin. The maximum difference in those with susceptible strains was 6.2%, showing that >93% received no antimicrobial benefits from the presence of clarithromycin.

5. Quantifying the Amount of Unnecessary Clarithromycin Used with Vonoprazan Triple Therapy

In Japan, the quantity of clarithromycin used per million cases treated using either the 200 or 400 mg b.i.d. approved dosages of clarithromycin (i.e., dose times duration times the number participants) would be, respectively, 2800 kg and 5600 kg. In the United States and Europe, where the clarithromycin dosage is 1 g/day for 14 days, the results per million treated is equivalent to 14,000 kg/year or 6.35 tons/year/million treated. In both instances, 80% to 90% of the clarithromycin would be unnecessary (i.e., misused). As noted above and evident in Figure 4, optimizing the vonoprazan–amoxicillin dual therapy should achieve equivalent or superior results without the need for clarithromycin.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/pharma3010006

References

- Li, Y.; Choi, H.; Leung, K.; Jiang, F.; Graham, D.Y.; Leung, W.K. Global prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection between 1980 and 2022: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2023, 8, 553–564.

- Graham, D.Y.; Hernaez, R.; Rokkas, T. Cross-roads for meta-analysis and network meta-analysis of H. pylori therapy. Gut 2022, 71, 643–650.

- Rokkas, T.; Gisbert, J.P.; Malfertheiner, P.; Niv, Y.; Gasbarrini, A.; Leja, M.; Megraud, F.; O’morain, C.; Graham, D.Y. Comparative Effectiveness of Multiple Different First-Line Treatment Regimens for Helicobacter pylori Infection: A Network Meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 2021, 161, 495–507.e4.

- Shah, S.; Hubscher, E.; Pelletier, C.; Jacob, R.; Vinals, L.; Yadlapati, R. Helicobacter pylori infection treatment in the United States: Clinical consequences and costs of eradication treatment failure. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 16, 341–357.

- Shah, S.C.; Iyer, P.G.; Moss, S.F. AGA Clinical Practice Update on the Management of Refractory Helicobacter pylori Infection: Expert Review. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 1831–1841.

- Hopkins, R.J. Current FDA-approved treatments for Helicobacter pylori and the FDA approval process. Gastroenterology 1997, 113, S126–S130.

- Hopkins, R.J.; Girardi, L.S.; Turney, E.A. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori eradication and reduced duodenal and gastric ulcer recurrence: A review. Gastroenterology 1996, 110, 1244–1252.

- Graham, D.Y.; Lew, G.M.; Klein, P.D.; Evans, D.G.; Evans, D.J., Jr.; Saeed, Z.A.; Malaty, H.M. Effect of treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection on the long- term recurrence of gastric or duodenal ulcer. A randomized, controlled study. Ann. Intern. Med. 1992, 116, 705–708.

- Graham, D.Y. Implications of the paradigm shift in management of Helicobacter pylori infections. Ther. Adv. Gastroenterol. 2023, 16, 17562848231160858.

- Tytgat, G.N.; Rauws, E.A.; de Koster, E.H. Campylobacter pylori. Diagnosis and treatment. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 1989, 11 (Suppl. S1), S49–S53.

- Axon, A.T. The role of omeprazole and antibiotic combinations in the eradication of Helicobacter pylori—An update. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. Suppl. 1994, 205, 31–37.

- Graham, D.Y. Illusions regarding Helicobacter pylori clinical trials and treatment guidelines. Gut 2017, 66, 2043–2046.

- Lee, Y.C.; Dore, M.P.; Graham, D.Y. Diagnosis and Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infection. Annu. Rev. Med. 2022, 73, 183–195.

- Ginnebaugh, B.D.; Baker, J.; Watts, L.; Saad, R.; Kao, J.; Chey, W.D. S1348 Triple Therapy for Primary Treatment of Helicobacter pylori: A 19-Year U.S. Single Center Experience. Off. J. Am. Coll. Gastroenterol. ACG 2020, 115, S680–S681.

- Nyssen, O.P.; Bordin, D.; Tepes, B.; Perez-Aisa, A.; Vaira, D.; Caldas, M.; Bujanda, L.; Castro-Fernandez, M.; Lerang, F.; Leja, M.; et al. European Registry on Helicobacter pylori management (Hp-EuReg): Patterns and trends in first-line empirical eradication prescription and outcomes of 5 years and 21,533 patients. Gut 2021, 70, 40–54.

- Essa, A.S.; Kramer, J.R.; Graham, D.Y.; Treiber, G. Meta-analysis: Four-drug, three-antibiotic, non-bismuth-containing “concomitant therapy” versus triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Helicobacter 2009, 14, 109–118.

- Matsumoto, H.; Shiotani, A.; Graham, D.Y. Current and Future Treatment of Helicobacter pylori Infections. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 11, 211–225.

- Graham, D.Y. Why the Vonoprazan Helicobacter pylori Therapies in the US-European Trial Produced Unacceptable Cure Rates. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2023, 68, 1691–1697.

- Graham, D.Y.; Lu, H.; Shiotani, A. Vonoprazan-containing Helicobacter pylori triple therapies contribution to global antimicrobial resistance. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 36, 1159–1163.

- Graham, D.Y. Hp-normogram (normo-graham) for assessing the outcome of H. pylori therapy: Effect of resistance, duration, and CYP2C19 genotype. Helicobacter 2015, 21, 85–90.

- Scott, D.; Weeks, D.; Melchers, K.; Sachs, G. The life and death of Helicobacter pylori. Gut 1998, 43 (Suppl. S1), S56–S60.

- Graham, D.Y.; Tansel, A. Interchangeable use of proton pump inhibitors based on relative potency. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 6, 800–808.

- Morino, Y.; Sugimoto, M.; Nagata, N.; Niikiura, R.; Iwata, E.; Hamada, M.; Kawai, Y.; Fujimiya, T.; Takeuchi, H.; Unezaki, S.; et al. Influence of Cytochrome P450 2C19 Genotype on Helicobacter pylori Proton Pump Inhibitor-Amoxicillin-Clarithromycin Eradication Therapy: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 759249.

- Öztürk, K.; Kurt, Ö.; Çelebi, G.; Şarlak, H.; Karakaya, M.F.; Demirci, H.; Kilinc, A.; Uygun, A. High-dose dual therapy is effective as first-line treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 31, 234–238.

- Guan, J.L.; Hu, Y.L.; An, P.; He, Q.; Long, H.; Zhou, L.; Chen, Z.F.; Xiong, J.G.; Wu, S.S.; Ding, X.W.; et al. Comparison of high-dose dual therapy with bismuth-containing quadruple therapy in Helicobacter pylori-infected treatment-naive patients: An open-label, multicenter, randomized controlled trial. Pharmacotherapy 2022, 42, 224–232.

- Yang, J.-C.; Lin, C.-J.; Wang, H.-L.; Chen, J.-D.; Kao, J.Y.; Shun, C.-T.; Lu, C.-W.; Lin, B.-R.; Shieh, M.-J.; Chang, M.-C.; et al. High-dose dual therapy is superior to standard first-line or rescue therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 13, 895–905.e5.

- Tai, W.-C.; Liang, C.-M.; Kuo, C.-M.; Huang, P.-Y.; Wu, C.-K.; Yang, S.-C.; Kuo, Y.-H.; Lin, M.-T.; Lee, C.-H.; Hsu, C.-N.; et al. A 14 day esomeprazole- and amoxicillin-containing high-dose dual therapy regimen achieves a high eradication rate as first-line anti-Helicobacter pylori treatment in Taiwan: A prospective randomized trial. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74, 1718–1724.

- Zhu, Z.; Lai, Y.; Ouyang, L.; Lv, N.; Chen, Y.; Shu, X. High-Dose Proton Pump Inhibitors Are Superior to Standard-Dose Proton Pump Inhibitors in High-Risk Patients with Bleeding Ulcers and High-Risk Stigmata After Endoscopic Hemostasis. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2021, 12, e00294.

- Hu, Y.; Xu, X.; Liu, X.-S.; He, C.; Ouyang, Y.-B.; Li, N.-S.; Xie, C.; Peng, C.; Zhu, Z.-H.; Xie, Y.; et al. Fourteen-day vonoprazan and low- or high-dose amoxicillin dual therapy for eradicating Helicobacter pylori infection: A prospective, open-labeled, randomized non-inferiority clinical study. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1049908.

- Ouyang, Y.; Wang, M.; Xu, Y.L.; Zhu, Y.; Lu, N.H.; Hu, Y. Amoxicillin-vonoprazan dual therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 37, 1666–1672.

- Hu, Y.; Xu, X.; Ouyang, Y.B.; He, C.; Li, N.S.; Xie, C.; Peng, C.; Zhu, Z.H.; Xie, Y.; Shu, X.; et al. Optimization of vonoprazan-amoxicillin dual therapy for eradicating Helicobacter pylori infection in China: A prospective, randomized clinical pilot study. Helicobacter 2022, 27, e12896.

- Liu, L.; Li, F.; Shi, H.; Nahata, M.C. The Efficacy and Safety of Vonoprazan and Amoxicillin Dual Therapy for Helicobacter pylori Infection: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 346.

- Zuberi, B.F.; Ali, F.S.; Rasheed, T.; Bader, N.; Hussain, S.M.; Saleem, A. Comparison of Vonoprazan and Amoxicillin Dual Therapy with Standard Triple Therapy with Proton Pump Inhibitor for Helicobacter pylori eradication: A Randomized Control Trial. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 38, 965–969.

- Murakami, K.; Sakurai, Y.; Shiino, M.; Funao, N.; Nishimura, A.; Asaka, M. Vonoprazan, a novel potassium-competitive acid blocker, as a component of first-line and second-line triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: A phase III, randomised, double-blind study. Gut 2016, 65, 1439–1446.

- Tsuda, M.; Asaka, M.; Kato, M.; Matsushima, R.; Fujimori, K.; Akino, K.; Kikuchi, S.; Lin, Y.; Sakamoto, N. Effect on Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy against gastric cancer in Japan. Helicobacter 2017, 22, e12415.

- Sholeh, M.; Khoshnood, S.; Azimi, T.; Mohamadi, J.; Kaviar, V.H.; Hashemian, M.; Karamollahi, S.; Sadeghifard, N.; Heidarizadeh, H.; Heidary, M.; et al. The prevalence of clarithromycin-resistant Helicobacter pylori isolates: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PeerJ 2023, 11, e15121.

- Chey, W.D.; Megraud, F.; Laine, L.; Lopez, L.J.; Hunt, B.J.; Howden, C.W. Vonoprazan Triple and Dual Therapy for Helicobacter pylori Infection in the United States and Europe: Randomized Clinical Trial. Gastroenterology 2022, 163, 608–619.

- Noda, H.; Noguchi, S.; Yoshimine, T.; Goji, S.; Adachi, K.; Tamura, Y.; Izawa, S.; Ebi, M.; Yamamoto, S.; Ogasawara, N.; et al. A Novel Potassium-Competitive Acid Blocker Improves the Efficacy of Clarithromycin-containing 7-day Triple Therapy against Helicobacter pylori. J. Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2016, 25, 283–288.

- Shinmura, T.; Adachi, K.; Yamaguchi, Y.; Izawa, S.; Hijikata, Y.; Ebi, M.; Funaki, Y.; Ogasawara, N.; Sasaki, M.; Kasugai, K. Vonoprazan-based triple therapy is effective for Helicobacter pylori eradication irrespective of clarithromycin susceptibility of Helicobacter pylori Infection. J. Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2019, 28, 389–395.

- Matsumoto, H.; Shiotani, A.; Katsumata, R.; Fujita, M.; Nakato, R.; Murao, T.; Ishii, M.; Kamada, T.; Haruma, K. Helicobacter pylori eradication with proton pump inhibitors or potassium-competitive acid blockers: The effect of clarithromycin reistance. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2016, 61, 3215–3220.

- Sue, S.; Kuwashima, H.; Iwata, Y.; Oka, H.; Arima, I.; Fukuchi, T.; Sanga, K.; Inokuchi, Y.; Ishii, Y.; Kanno, M.; et al. The Superiority of Vonoprazan-based First-line Triple Therapy with Clarithromycin: A Prospective Multi-center Cohort Study on Helicobacter pylori Eradication. Intern. Med. 2017, 56, 1277–1285.

- Saito, Y.; Konno, K.; Sato, M.; Nakano, M.; Kato, Y.; Saito, H.; Serizawa, H. Vonoprazan-Based Third-Line Therapy Has a Higher Eradication Rate against Sitafloxacin-Resistant Helicobacter pylori. Cancers 2019, 11, 116.

- Horie, R.; Handa, O.; Ando, T.; Ose, T.; Murakami, T.; Suzuki, N.; Sendo, R.; Imamoto, E.; Itoh, Y. Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy outcome according to clarithromycin susceptibility testing in Japan. Helicobacter 2020, 25, e12698.

- Sugimoto, M.; Hira, D.; Murata, M.; Kawai, T.; Terada, T. Effect of Antibiotic Susceptibility and CYP3A4/5 and CYP2C19 Genotype on the Outcome of Vonoprazan-Containing Helicobacter pylori Eradication Therapy. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 645.

- Sue, S.; Ogushi, M.; Arima, I.; Kuwashima, H.; Nakao, S.; Naito, M.; Komatsu, K.; Kaneko, H.; Tamura, T.; Sasaki, T.; et al. Vonoprazan- vs proton-pump inhibitor-based first-line 7-day triple therapy for clarithromycin-susceptible Helicobacter pylori: A multicenter, prospective, randomized trial. Helicobacter 2018, 23, e12456.

- Okubo, H.; Akiyama, J.; Kobayakawa, M.; Kawazoe, M.; Mishima, S.; Takasaki, Y.; Nagata, N.; Shimada, T.; Yokoi, C.; Komori, S.; et al. Vonoprazan-based triple therapy is effective for Helicobacter pylori eradication irrespective of clarithromycin susceptibility. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 55, 1054–1061.

- Ang, D.; Koo, S.H.; Chan, Y.H.; Tan, T.Y.; Soon, G.H.; Tan, C.K.; Soon, G.H.; Tan, C.K.; Lin, K.W.; Krishnasamy-Balasubramanian, J.-K.; et al. Clinical trial: Seven-day vonoprazan- versus 14-day proton pump inhibitor-based triple therapy for first-line Helicobacter pylori eradication. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2022, 56, 436–449.

- Suzuki, S.; Gotoda, T.; Kusano, C.; Ikehara, H.; Ichijima, R.; Ohyauchi, M.; Ito, M.; Kawamura, M.; Ogata, Y.; Ohtaka, M.; et al. Seven-day vonoprazan and low-dose amoxicillin dual therapy as first-line Helicobacter pylori treatment: A multicentre randomised trial in Japan. Gut 2020, 69, 1019–1026.

- Suzuki, S.; Gotoda, T.; Kusano, C.; Iwatsuka, K.; Moriyama, M. The Efficacy and Tolerability of a Triple Therapy Containing a Potassium-Competitive Acid Blocker Compared With a 7-Day PPI-Based Low-Dose Clarithromycin Triple Therapy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 111, 949–956.

- Ratana-Amornpin, S.; Sanglutong, L.; Eiamsitrakoon, T.; Siramolpiwat, S.; Graham, D.Y.; Mahachai, V. Pilot studies of vonoprazan-containing Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy suggest Thailand may be more similar to the US than Japan. Helicobacter 2023, 28, e13019.

- FDA. Vonoprazan Package Insert; FDA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2022.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!