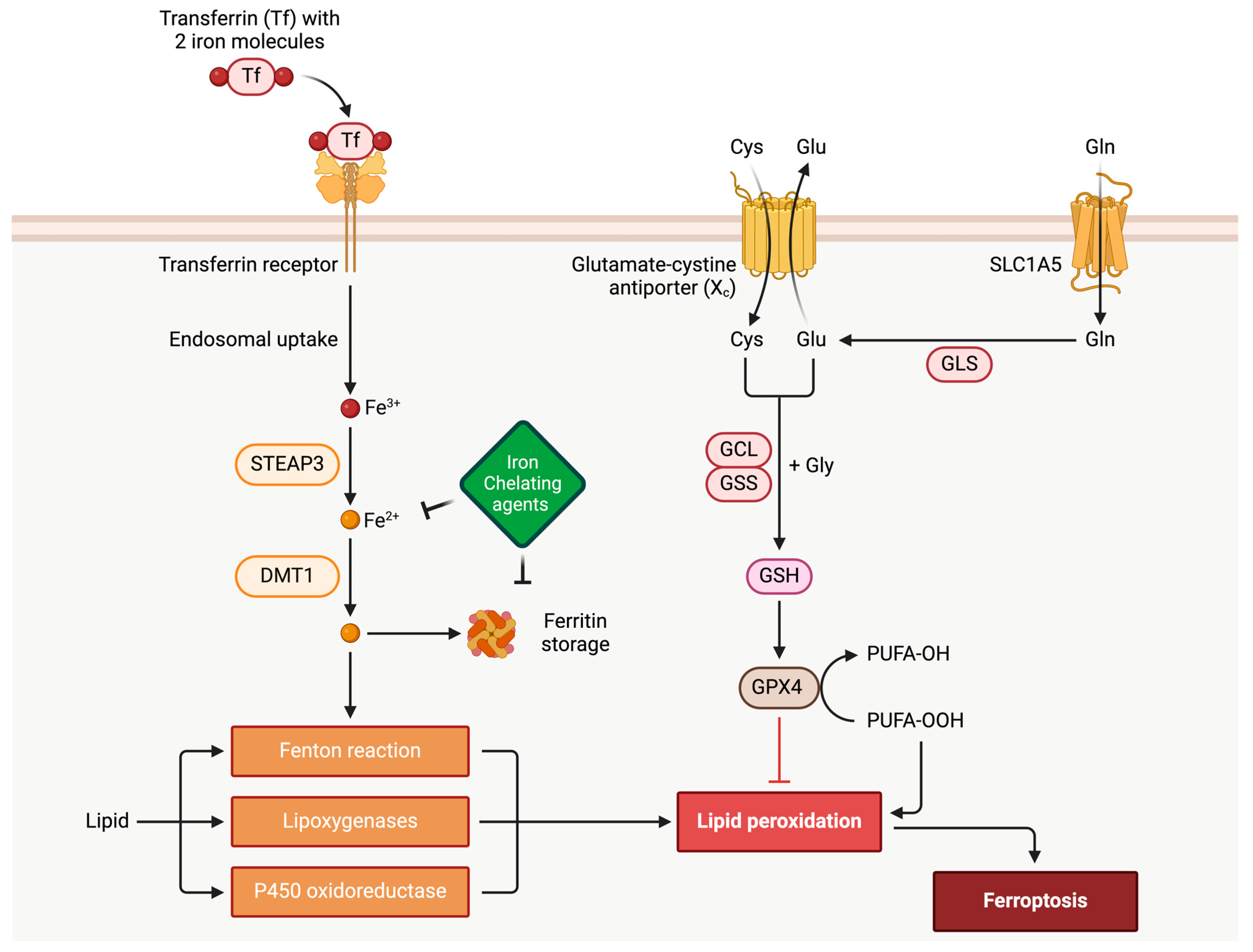

In the realm of cardiovascular diseases, it significantly contributes to cardiomyopathies, including dilated cardiomyopathy, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, and restrictive cardiomyopathy. Ferroptosis involves intricate interactions within cellular iron metabolism, lipid peroxidation, and the balance between polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fatty acids. Molecularly, factors like p53 and nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (Nrf2) impact cellular susceptibility to ferroptosis under oxidative stress. Understanding ferroptosis is vital in cardiomyopathies, where cardiac myocytes heavily depend on aerobic respiration, with iron playing a pivotal role. Dysregulation of the antioxidant enzyme glutathione peroxidase (GPX4) is linked to cardiomyopathies, emphasizing its significance. Ferroptosis’s role in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury, exacerbated in diabetes, underscores its relevance in cardiovascular conditions.

- ferroptosis

- GPX4

- NRF2

- GSH

- oxidative stress

- cardiomyopathy

1. Introduction to Ferroptosis

2. Ferroptosis Implication in Cardiac Myocytes and Cardiovascular Disease

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/biomedicines12030558

References

- Jiang, X.; Stockwell, B.R.; Conrad, M. Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021, 22, 266–282.

- Farina, M.; Ávila, D.S.; Da Rocha, J.B.T.; Aschner, M. Metals, oxidative stress and neurodegeneration: A focus on iron, manganese and mercury. Neurochem. Int. 2013, 62, 575–594.

- Carbone, M.; Melino, G. Lipid metabolism offers anticancer treatment by regulating ferroptosis. Cell Death Differ. 2019, 26, 2516–2519.

- Vos, T.; Lim, S.S.; Abbafati, C.; Abbas, K.; Abbasi, M.; Abbasifard, M.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abbastabar, H.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abdelalim, A.; et al. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396, 1204–1222.

- Arnett, D.K.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Albert, M.A.; Buroker, A.B.; Goldberger, Z.D.; Hahn, E.J.; Himmelfarb, C.D.; Khera, A.; Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; McEvoy, J.W.; et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: Executive Summary. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 74, 1376–1414.

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Addolorato, G.; Ammirati, E.; Baddour, L.M.; Barengo, N.C.; Beaton, A.Z.; Benjamin, E.J.; Benziger, C.P.; et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990–2019: Update from the GBD 2019 Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2982–3021.

- Whelan, R.S.; Kaplinskiy, V.; Kitsis, R.N. Cell death in the Pathogenesis of heart disease: Mechanisms and significance. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2010, 72, 19–44.

- Moe, G.W.; Marín-García, J. Role of cell death in the progression of heart failure. Heart Fail. Rev. 2016, 21, 157–167.

- Del Re, D.P.; Amgalan, D.; Linkermann, A.; Liu, Q.; Kitsis, R.N. Fundamental mechanisms of regulated cell death and implications for heart disease. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 1765–1817.

- Dixon, S.J.; Lemberg, K.M.; Lamprecht, M.R.; Skouta, R.; Zaitsev, E.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Patel, D.N.; Bauer, A.J.; Cantley, A.M.; Yang, W.S.; et al. Ferroptosis: An Iron-Dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060–1072.

- Huang, F.; Yang, R.; Xiao, Z.; Xie, Y.; Lin, X.; Zhu, P.; Zhou, P.; Lu, J.; Zheng, S. Targeting ferroptosis to treat cardiovascular diseases: A new continent to be explored. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 737971.

- Gao, M.; Monian, P.; Quadri, N.; Ramasamy, R.; Jiang, X. Glutaminolysis and transferrin regulate ferroptosis. Mol. Cell 2015, 59, 298–308.

- Fang, X.; Wang, H.; Han, D.; Xie, E.; Xiang, Y.; Wei, J.; Gu, S.; Gao, F.; Zhu, N.; Yin, X.; et al. Ferroptosis as a target for protection against cardiomyopathy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 2672–2680.

- Wang, Y.; Tang, M. PM2.5 induces ferroptosis in human endothelial cells through iron overload and redox imbalance. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 254, 112937.

- Ravingerova, T.; Kindernay, L.; Bartekova, M.; Ferko, M.; Adameova, A.; Zohdi, V.; Bernatova, I.; Ferenczyova, K.; Lazou, A. The molecular mechanisms of iron metabolism and its role in cardiac dysfunction and cardioprotection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 7889.

- Wu, X.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, X. Ferroptosis as a novel therapeutic target for cardiovascular disease. Theranostics 2021, 11, 3052–3059.

- Liang, D.; Minikes, A.M.; Jiang, X. Ferroptosis at the intersection of lipid metabolism and cellular signaling. Mol. Cell 2022, 82, 2215–2227.

- Barbosa, P.; Abo El-Magd, N.F.; Hesketh, J.; Bermano, G. The Role of rs713041 Glutathione Peroxidase 4 (GPX4) Single Nucleotide Polymorphism on Disease Susceptibility in Humans: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15762.

- Liu, J.; Kang, R.; Tang, D. Signaling pathways and defense mechanisms of ferroptosis. FEBS J. 2021, 289, 7038–7050.

- Li, Y.; Cao, Y.; Xiao, J.; Shang, J.; Tan, Q.; Feng, P.; Huang, W.; Wu, F.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, X. Inhibitor of apoptosis-stimulating protein of p53 inhibits ferroptosis and alleviates intestinal ischemia/reperfusion-induced acute lung injury. Cell Death Differ. 2020, 27, 2635–2650.

- Ma, W.Q.; Sun, X.J.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, N.F. Metformin attenuates hyperlipidaemia-associated vascular calcification through anti-ferroptotic effects. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2021, 165, 229–242.

- Tarangelo, A.; Magtanong, L.; Bieging-Rolett, K.T.; Li, Y.; Ye, J.; Attardi, L.D.; Dixon, S.J. p53 Suppresses Metabolic Stress-Induced Ferroptosis in Cancer Cells. Cell Rep. 2018, 22, 569–575.

- Ve Venkatesh, D.; Stockwell, B.R.; Prives, C. p21 can be a barrier to ferroptosis independent of p53. Aging 2020, 12, 17800–17814.

- Xie, Y.; Zhu, S.; Song, X.; Sun, X.; Fan, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhong, M.; Yuan, H.; Zhang, L.; Billiar, T.R.; et al. The Tumor Suppressor p53 Limits Ferroptosis by Blocking DPP4 Activity. Cell Rep. 2017, 20, 1692–1704.

- Gao, M.; Yi, J.; Zhu, J.; Minikes, A.M.; Monian, P.; Thompson, C.B.; Jiang, X. Role of Mitochondria in Ferroptosis. Mol. Cell 2019, 73, 354–363.e3.

- Hoshino, A.; Mita, Y.; Okawa, Y.; Ariyoshi, M.; Iwai-Kanai, E.; Ueyama, T.; Ikeda, K.; Ogata, T.; Matoba, S. Cytosolic p53 inhibits Parkin-mediated mitophagy and promotes mitochondrial dysfunction in the mouse heart. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2308.

- Doll, S.; Proneth, B.; Tyurina, Y.Y.; Panzilius, E.; Kobayashi, S.; Ingold, I.; Irmler, M.; Beckers, J.; Aichler, M.; Walch, A.; et al. ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular lipid composition. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2017, 13, 91–98.

- Liu, Y.; Gu, W. p53 in ferroptosis regulation: The new weapon for the old guardian. Cell Death Differ. 2022, 29, 895–910.

- Das, D.K.; Engelman, R.M.; Rousou, J.A.; Breyer, R.H. Aerobic vs. anaerobic metabolism during ischemia in heart muscle. Ann. Chir. Gynaecol. 1987, 76, 68–76.

- Ventura-Clapier, R.; Garnier, A.; Veksler, V.; Joubert, F. Bioenergetics of the failing heart. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2011, 1813, 1360–1372.

- Fu, C.; Cao, N.; Zeng, S.; Zhu, W.; Fu, X.; Liu, W.; Fan, S. Role of mitochondria in the regulation of ferroptosis and disease. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1301822.

- Li, C.; Liu, J.; Hou, W.; Kang, R.; Tang, D. STING1 Promotes Ferroptosis Through MFN1/2-Dependent Mitochondrial Fusion. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 698679.

- Willems, P.H.; Rossignol, R.; Dieteren, C.E.; Murphy, M.P.; Koopman, W.J. Redox Homeostasis and Mitochondrial Dynamics. Cell Metab. 2015, 22, 207–218.

- Jang, S.; Chapa-Dubocq, X.R.; Tyurina, Y.Y.; St. Croix, C.M.; Kapralov, A.A.; Tyurin, V.A.; Bayır, H.; Kagan, V.E.; Javadov, S. Elucidating the contribution of mitochondrial glutathione to ferroptosis in cardiomyocytes. Redox Biol. 2021, 45, 102021.

- Yang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Xie, S.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Chen, L.; Mao, M.; Chen, C.; Huang, A.; Chen, Y.; et al. Metformin induces Ferroptosis by inhibiting UFMylation of SLC7A11 in breast cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2021, 40, 206.

- Kajarabille, N.; Latunde-Dada, G.O. Programmed Cell-Death by Ferroptosis: Antioxidants as Mitigators. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 4968.

- Takashi, Y.; Tomita, K.; Kuwahara, Y.; Roudkenar, M.H.; Roushandeh, A.M.; Igarashi, K.; Nagasawa, T.; Nishitani, Y.; Sato, T. Mitochondrial dysfunction promotes aquaporin expression that controls hydrogen peroxide permeability and ferroptosis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020, 161, 60–70.

- Rojas, M.L.; Cruz Del Puerto, M.M.; Flores-Martín, J.; Racca, A.C.; Kourdova, L.T.; Miranda, A.L.; Panzetta-Dutari, G.M.; Genti-Raimondi, S. Role of the lipid transport protein StarD7 in mitochondrial dynamics. Biochimica et biophysica acta. Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2021, 1866, 159029.

- Deshwal, S.; Onishi, M.; Tatsuta, T.; Bartsch, T.; Cors, E.; Ried, K.; Lemke, K.; Nolte, H.; Giavalisco, P.; Langer, T. Mitochondria regulate intracellular coenzyme Q transport and ferroptotic resistance via STARD7. Nat. Cell Biol. 2023, 25, 246–257.

- Wu, S.; Mao, C.; Kondiparthi, L.; Poyurovsky, M.V.; Olszewski, K.; Gan, B. A ferroptosis defense mechanism mediated by glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase 2 in mitochondria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2121987119.

- Hentze, M.W.; Muckenthaler, M.U.; Galy, B.; Camaschella, C. Two to tango: Regulation of mammalian iron metabolism. Cell 2010, 142, 24–38.

- Mancias, J.D.; Wang, X.; Gygi, S.P.; Harper, J.W.; Kimmelman, A.C. Quantitative proteomics identifies NCOA4 as the cargo receptor mediating ferritinophagy. Nature 2014, 509, 105–109.

- Nemeth, E.; Tuttle, M.S.; Powelson, J.; Vaughn, M.B.; Donovan, A.; Ward, D.M.; Ganz, T.; Kaplan, J. Hepcidin regulates cellular iron efflux by binding to ferroportin and inducing its internalization. Science 2004, 306, 2090–2093.

- Nemeth, E.; Ganz, T. Hepcidin-Ferroportin interaction controls systemic iron homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6493.

- Lakhal-Littleton, S.; Wolna, M.; Carr, C.A.; Miller, J.J.; Christian, H.C.; Ball, V.; Santos, A.L.; Diaz, R.; Biggs, D.F.; Stillion, R.J.; et al. Cardiac ferroportin regulates cellular iron homeostasis and is important for cardiac function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 3164–3169.

- Weaver, K.; Skouta, R. The selenoprotein glutathione peroxidase 4: From molecular mechanisms to novel therapeutic opportunities. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 891.

- Brigelius-Flohé, R.; Maiorino, M. Glutathione peroxidases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta-Gen. Subj. 2013, 1830, 3289–3303.

- Bridges, R.J.; Natale, N.R.; Patel, S.A. System xc⁻ cystine/glutamate antiporter: An update on molecular pharmacology and roles within the CNS. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012, 165, 20–34.

- Xie, Y.; Hou, W.; Song, X.; Yu, Y.; Huang, J.; Sun, X.; Kang, R.; Tang, D. Ferroptosis: Process and function. Cell Death Differ. 2016, 23, 369–379.

- Angeli, J.P.F.; Schneider, M.; Proneth, B.; Tyurina, Y.Y.; Tyurin, V.A.; Hammond, V.J.; Herbach, N.; Aichler, M.; Walch, A.; Eggenhofer, E.; et al. Inactivation of the ferroptosis regulator Gpx4 triggers acute renal failure in mice. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014, 16, 1180–1191.

- Zilka, O.; Shah, R.; Li, B.; Angeli, J.P.F.; Griesser, M.; Conrad, M.; Pratt, D.A. On the Mechanism of Cytoprotection by Ferrostatin-1 and Liproxstatin-1 and the Role of Lipid Peroxidation in Ferroptotic Cell Death. ACS Cent. Sci. 2017, 3, 232–243.

- Tadokoro, T.; Ikeda, M.; Ide, T.; Deguchi, H.; Ikeda, S.; Okabe, K.; Ishikita, A.; Matsushima, S.; Koumura, T.; Yamada, K.I.; et al. Mitochondria-dependent ferroptosis plays a pivotal role in doxorubicin cardiotoxicity. JCI Insight 2020, 5, e132747.

- Eltzschig, H.K.; Eckle, T. Ischemia and reperfusion—From mechanism to translation. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 1391–1401.

- Tang, L.; Luo, X.; Tu, H.; Chen, H.; Xiong, X.; Li, N.; Peng, J. Ferroptosis occurs in phase of reperfusion but not ischemia in rat heart following ischemia or ischemia/reperfusion. Naunyn-Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 2020, 394, 401–410.

- Zhang, W.; Sun, Z.; Meng, F. Schisandrin B ameliorates myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion injury through attenuation of endoplasmic reticulum Stress-Induced apoptosis. Inflammation 2017, 40, 1903–1911.

- Dixon, S.J.; Patel, D.N.; Welsch, M.; Skouta, R.; Lee, E.D.; Hayano, M.; Thomas, A.G.; Gleason, C.E.; Tatonetti, N.P.; Slusher, B.S.; et al. Pharmacological inhibition of cystine–glutamate exchange induces endoplasmic reticulum stress and ferroptosis. eLife 2014, 3, e02523.

- Wu, D.A.; Zhang, K.; Hu, P. The role of autophagy in acute myocardial infarction. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 551.

- Chen, H.Y.; Xiao, Z.Z.; Xiao, L.; Xu, R.; Zhu, P.; Zheng, S.Y. ELAVL1 is transcriptionally activated by FOXC1 and promotes ferroptosis in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by regulating autophagy. Mol. Med. 2021, 27, 14.

- Hansen, S.S.; Aasum, E.; Hafstad, A.D. The role of NADPH oxidases in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2018, 1864, 1908–1913.

- Rabinovitch, R.C.; Samborska, B.; Faubert, B.; Ma, E.H.; Gravel, S.; Andrzejewski, S.; Raissi, T.C.; Pause, A.; St.-Pierre, J.; Jones, R.G. AMPK Maintains Cellular Metabolic Homeostasis through Regulation of Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species. Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 1–9.

- Wang, C.; Zhu, L.; Yuan, W.; Sun, L.; Xia, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Yao, W. Diabetes aggravates myocardial ischaemia reperfusion injury via activating Nox2-related programmed cell death in an AMPK-dependent manner. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2020, 24, 6670–6679.

- Dillmann, W.H. Diabetic cardiomyopathy. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 1160–1162.

- Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Zhou, W.; Men, H.; Bao, T.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Q.; Tan, Y.; Keller, B.B.; Tong, Q.; et al. Ferroptosis is essential for diabetic cardiomyopathy and is prevented by sulforaphane via AMPK/NRF2 pathways. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2022, 12, 708–722.

- Zhu, Y.; Xian, X.; Wang, Z.; Bi, Y.; Chen, Q.; Han, X.; Tang, D.; Chen, R. Research Progress on the Relationship between Atherosclerosis and Inflammation. Biomolecules 2018, 8, 80.

- Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Ye, T.; Yang, L.; Shen, Y.; Li, H. Ferroptosis signaling and regulators in atherosclerosis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 809457.

- Zhao, Y.; Lu, J.; Mao, A.; Zhang, R.; Guan, S. Autophagy inhibition plays a protective role in ferroptosis induced by alcohol via the P62–KeaP1–NRF2 pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 9671–9683.

- Jiang, L.; Kon, N.; Li, T.; Wang, S.; Su, T.; Hibshoosh, H.; Baer, R.; Gu, W. Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated activity during tumour suppression. Nature 2015, 520, 57–62.

- Ye, Y.; Chen, A.; Li, L.; Liang, Q.; Wang, S.; Dong, Q.; Fu, M.; Lan, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, X.; et al. Repression of the antiporter SLC7A11/glutathione/glutathione peroxidase 4 axis drives ferroptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells to facilitate vascular calcification. Kidney Int. 2022, 102, 1259–1275.

- Fang, X.; Ardehali, H.; Min, J.; Wang, F. The molecular and metabolic landscape of iron and ferroptosis in cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2022, 20, 7–23.