Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Certified music therapists use music within therapeutic relationships to address human needs, health, and well-being with a variety of populations. Palliative care and music therapy are holistic and diverse fields, adapting to unique issues within end-of-life contexts. Palliative care music therapy has been formally practiced since the late 1970s and affords a variety of benefits, including pain and anxiety reduction, enhancement of quality of life, emotional expression, and relationship completion.

- palliative care

- music therapy

- end-of-life

1. Introduction

A palliative care approach aims to improve quality of life and mitigate suffering for those navigating terminal or life-limiting illnesses. Palliative care occurs in various contexts: in-home support, inpatient palliative care units within hospital settings, long-term care facilities, retirement residences, residential hospices, community hospices, and community agency programs. Hospices typically also offer day wellness programs for those negotiating life-threatening or life-limiting illness, and bereavement care for those grieving the death of their loved one.

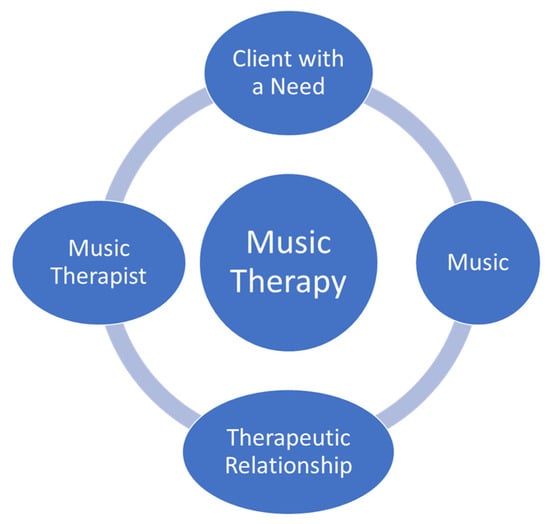

Music and music therapy experiences are becoming more common in end-of-life care contexts [1][2][3][4]. Music therapists are allied healthcare professionals who provide music therapy experiences to persons at end of life, often in collaboration with the interdisciplinary team [3]. “Music Therapists (MTAs) use music purposefully within therapeutic relationships to support development, health, and well-being. Music therapists use music safely and ethically to address human needs within cognitive, communicative, emotional, musical, physical, social, and spiritual domains” ([5], para #1). There are many music opportunities in end-of-life care, ranging from entertainment to recreational music to music therapy. Each experience has value but is also different. For an experience to be considered music therapy, four elements are needed: a music therapist, client with a need, music, and a therapeutic relationship [6]. See Figure 1.

Figure 1. Elements of the music therapy experience.

Clements-Cortés and Bartel [7] share a four-level model for mechanisms of response in music therapy which includes learned cognitive responses, cognitive activation, stimulated neural coherence, and cellular genetic responses. Researchers have also highlighted the scientific basis for standardized therapeutic music experiences clustered into the sensorimotor, speech/language, and cognitive domains [8]. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews offer scientific evidence that music therapy can support a wide range of symptom improvements, including pain and anxiety [9][10][11][12][13][14]. Further research and descriptive articles point to the efficacy of music therapy for relationship completion [15], emotional expression [16], and improvements in heart rate, blood pressure, augmented relaxation, and wellness [4]. Similarly, McConnell and Porter [17] highlight enhanced physical comfort, increased emotional well-being, enhanced social interaction, and improved spiritual well-being as valuable outcomes of music therapy at end of life.

Palliative care and music therapy are both holistic and diverse fields, continually adapting to unique issues in these end-of-life contexts. Palliative care music therapy aims to improve quality of life while supporting goals such as symptom management, emotion regulation, communication, and spiritual expression [4]. Clements-Cortés [18] found that both live and recorded music provided in music therapy treatment resulted in statistically significant reductions in pain perception and the enhancement of physical comfort.

The thematic analysis of palliative care music therapy research and practice highlights that music therapy addresses physical, psychosocial, and whole-person care [19]. These experiences may include receptive and active interventions such as singing, playing instruments, songwriting, clinical improvisation, and guided relaxation, based on evidence and best practices. For example, Vesel and Dave [20] note the benefit of music therapy for supporting pain management, increasing energy and quality of life while decreasing anxiety. Similarly, Gallagher et al. [21] also found music therapy assisted with anxiety and stress reduction as well as perceived pain level, overall quality of life, mood improvement, and acceptance of death.

Reidy and MacDonald [22] note: “Ongoing barriers to music therapy include the challenge to obtain adequate sustainable funding and the misunderstanding of music therapy as entertainment” (p. 1605). Funding for music therapy services varies considerably depending on the country, province, state, and location of care. In hospice or inpatient palliative care settings, if there is a music therapist on the interdisciplinary team the patient would not necessarily pay for music therapy, as it would be covered by their fees to be in that setting, insurance, or the government. However, for example, only 6% of hospice programs employ music therapists [20]. It is typical that a patient would pay for the service if they were receiving palliative care in the community in Canada. Customarily, fees for the clinical supervision of music therapy pre-professionals’ internships in palliative care are either covered by university training programs (when considered a placement course), and/or by the organization that employs the music therapist (on staff or contract) if clinical supervision is included in the job responsibilities.

Training to be a therapist and professional caregiver for those who are dying is a rewarding but challenging process. Where the authors reside and practice as registered music psychotherapists, we adhere to the requirements as outlined by the College of Registered Psychotherapists of Ontario wherein the supervisor must adhere to the following:

-

Be a member in good standing of a regulatory college;

-

Have five years’ extensive clinical experience;

-

Complete 1000 direct client contact hours and 150 h of clinical supervision;

-

Provide a signed declaration noting they understand CRPO’s definitions of clinical supervision, clinical supervisor, and the scope of practice of psychotherapy [23].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/healthcare12040459

References

- Hilliard, R.E. Music Therapy in Hospice and Palliative Care: A Review of the Empirical Data. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2005, 2, 173–178.

- Pommeret, S.; Chrusciel, J.; Verlaine, C.; Filbet, M.; Tricou, C.; Sanchez, S.; Hannetel, L. Music in palliative care: A qualitative study with patients suffering from cancer. BMC Palliat. Care 2019, 18, 78.

- Srolovitz, M.; Borgwardt, J.; Burkart, M.; Clements-Cortés, A.; Czamanski-Cohen, J.; Ortiz Guzman, M.; Hicks, M.G.; Kaimal, G.; Lederman, L.; Potash, J.S.; et al. Top ten tips palliative care clinicians should know about music therapy and art therapy. J. Palliat. Med. 2021, 25, 135–144.

- Warth, M.; Kessler, J.; Hillecke, T.K.; Bardenheuer, H.J. Trajectories of Terminally Ill Patients’ Cardiovascular Response to Receptive Music Therapy in Palliative Care. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2016, 52, 196–204.

- Canadian Association of Music Therapists. What Is Music Therapy? 2020. Available online: https://www.musictherapy.ca/about-camt-music-therapy/about-music-therapy/ (accessed on 11 December 2023).

- Bradt, J.; Dileo, C.; Shim, M. Music interventions for pre-operative anxiety. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 6, CD006908.

- Clements-Cortés, A.; Bartel, L. Are we doing more than we know? Possible mechanisms of response to music therapy. Front. Med. 2018, 5, 255.

- Thaut, M.; Francisco, G.; Hoemberg, V. Editorial: The Clinical Neuroscience of Music: Evidence Based Approaches and Neurologic Music Therapy. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 740329.

- Bradt, J.; Dileo, C. Music therapy for end-of-life care. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010, 1, CD007169.

- Gutgsell, K.J.; Schluchter, M.; Margevicius, S.; DeGolia, P.A.; McLaughlin, B.; Harris, M.; Mecklenburg, J.; Wiencek, C. Music therapy reduces pain in palliative care patients: A randomized controlled trial. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2013, 45, 822–831.

- Horne-Thompson, A.; Grocke, D. The effect of music therapy on anxiety in patients who are terminally ill. J. Palliat. Med. 2008, 11, 582–590.

- Köhler, F.; Martin, Z.S.; Hertrampf, R.S.; Gäbel, C.; Kessler, J.; Ditzen, B.; Warth, M. Music Therapy in the Psychosocial Treatment of Adult Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 651.

- Lee, J.H. The Effects of Music on Pain: A Meta-Analysis. J. Music Ther. 2016, 53, 430–477.

- Schmid, W.; Rosland, J.H.; von Hofacker, S.; Hunskår, I.; Bruvik, F. Patient’s and health care provider’s perspectives on music therapy in palliative care—An integrative review. BMC Palliat. Care 2018, 17, 32.

- Clements-Cortés, A.; Yip, J. (Eds.) Relationship Completion in Palliative Care Music Therapy; Barcelona: Gilsum, NH, USA, 2021.

- Clements-Cortés A: The use of music in facilitating emotional expression in the terminally ill. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Med. 2004, 21, 255–260.

- McConnell, T.; Porter, S. The experience of providing end of life care at a children’s hospice: A qualitative study. BMC Palliat. Care 2017, 16, 15.

- Clements-Cortés, A. The effect of live music vs. taped music on pain and comfort in palliative care. Korean J. Music Ther. 2011, 13, 105–121.

- Clements-Cortes, A. Music therapy in end-of-life care: A review of the literature. In Voices of the Dying and Bereaved: Music Therapy Narratives; Clements-Cortes, A., Varvas Klinck, S., Eds.; Barcelona Publishers: Gilsum, NH, USA, 2016; pp. 5–34.

- Vesel, T.; Dave, S.; Soham, D. Music therapy and palliative care: Systematic review. J. Pain Symptom Manag. 2018, 56, e74.

- Gallagher, L.M.; Lagman, R.; Walsh, D.; Davis, M.P.; LeGrand, S.B. The clinical effects of music therapy in palliative medicine. Support. Care Cancer 2006, 14, 859–866.

- Reidy, J.; MacDonald, M.C. Use of palliative care music therapy in a hospital setting during COVID-19. J. Palliat. Med. 2021, 24, 1603–1605.

- College of Registered Psychotherapists of Ontario. Supervision. 2024. Available online: https://www.crpo.ca/supervision/#supervision_requirements (accessed on 9 January 2024).

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!