1. Introduzione alla sostenibilità e allo sviluppo sostenibile

Il concetto di

sostenibilità , o

sviluppo sostenibile , è stato introdotto nel 1987 attraverso il Rapporto Brundtland delle Nazioni Unite, in cui viene definito come “uno sviluppo che soddisfa i bisogni del presente senza compromettere la capacità delle generazioni future di soddisfare i propri bisogni” [

5 ].

Il forte e doveroso impulso contenuto nel citato rapporto a tutela dei Paesi in crisi o in via di sviluppo non ha, però, distratto l’attenzione della Commissione Crisi Urbana da quanto accadeva e accade nelle città del mondo industriale, dato che queste “rappresentano una quota elevata di utilizzo delle risorse globali, consumo di energia e inquinamento ambientale”. Infatti, a causa del loro comportamento e delle loro esigenze, molte di queste città hanno un impatto che va oltre i loro confini urbani, ricavando “risorse ed energia da territori lontani, con enormi impatti complessivi sugli ecosistemi di queste terre” [

5 ].

2. Il settore delle costruzioni e gli approcci alla sostenibilità nel contesto globale

L’industria delle costruzioni è una macchina complessa e articolata e, allo stesso tempo, decisiva per l’economia mondiale (e, di conseguenza, per ogni singola nazione). Per una lettura più chiara di queste affermazioni, guardiamo i dati sul volume d’affari sostenuto nel 2021, anno della ripresa dopo l’avvento del virus SARS-CoV-2. Il valore di mercato del settore edile in quell’anno ammontava a 7,8 trilioni di dollari e, con un volume di spesa produttiva di 13,2 trilioni di dollari e oltre 180 milioni di lavoratori impiegati in tutto il mondo, ha registrato ricavi per oltre 12 trilioni di dollari. Secondo gli esperti del settore, queste cifre dovrebbero aumentare nei prossimi anni e si prevede che nel 2030, con un volume di spesa di 14,4 trilioni di dollari, i ricavi supereranno i 22 trilioni di dollari [

6 ,

7 ,

8 ]. Solo in Italia, spinto dagli incentivi fiscali proposti dallo Stato, come

il Bonus 110 , il settore delle costruzioni è cresciuto del 27% nel 2022[

9 ].

Per affrontare il tema della sostenibilità – concetto di per sé troppo vasto, anche se ristretto al campo delle costruzioni – si è cercato negli anni di semplificarlo scomponendo il problema

in più variabili o ambiti di intervento. Per questo motivo, sebbene l’obiettivo finale sia sempre quello di ridurre l’impatto generato dal settore delle costruzioni, in termini specifici si è iniziato a fare riferimento a tre diverse tipologie di sostenibilità interconnesse:

ambientale ,

sociale ed

economico-finanziaria . Anche il CEN (Comitato Europeo di Normazione) ha cercato negli anni di dare il proprio contributo supportando le diverse professionalità coinvolte nel settore AEC dettando le regole di questo nuovo modo di concepire l’architettura. Ad esempio, gli ultimi aggiornamenti delle norme UNI EN ISO 14008—

Valutazione monetaria degli impatti ambientali e dei relativi aspetti ambientali e UNI EN ISO 14006—

Sistemi di gestione ambientale—Linee guida per l'integrazione della progettazione ecocompatibile risalgono rispettivamente al 2019 e al 2020 [

10 ,

11 ].

3. L'intersezione tra sostenibilità, cambiamento climatico e COVID-19

The concept of sustainability is closely linked to climate change issues, and for this reason, in 2022, the European Commission “committed to supporting the integration of climate resilience considerations into the construction and renovation of buildings”, by commissioning the Danish consultancy Ramboll and the CE Deft, a Dutch research and consultancy centre, to undertake “a study to collect and synthesise existing methods, specifications, best practices, and guidelines for climate resilient buildings” with the final aim of drafting guidelines entitled

EU-level technical guidance on adapting buildings to climate change [

12].

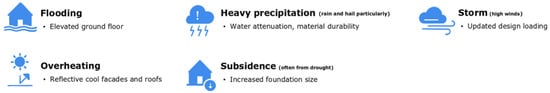

One of the main goals of these guidelines will be to mitigate the priority risks that may affect buildings due to climate change so as to achieve an in-depth review of vulnerability and climate risk assessment methodologies (see Figure 1, RAMBOLL infographic).

Figure 1. Infographic on priority risks that can affect buildings.

This research examines a multitude of documents of various types and provenance from recent studies undertaken by the European Union and academic studies, until the regulatory instruments that guide the building sector in each individual country, “will consider any variation required for different scales of buildings, from the individual to the whole block, providing feedback on the impact, ease of use, and synergies/conflicts of the methodologies” [

12].

4. COVID-19 Implications of Environmental and Economic Sustainability

In the field of environmental sustainability, with regard to the problem of climate change, research has already been trying to make its contribution for several years, but three years ago the world was shaken by a totally unexpected event, the COVID-19 pandemic.

This worldwide pandemic upset and transformed, in the space of just a few months, the way people behaved and the way they perceived the world around them, drastically altering their perception of the spaces and environments in which they daily lived, worked, or simply spent their free time [

13].

The link between the advent of COVID-19 and sustainability consists of a multiplicity of psycho-sociological and perceptual aspects, such as the fact that the occupancy pattern of buildings turns out to be one of the determining factors in assessing the energy performance and sustainability of buildings [

14].

During the pandemic, due to the lockdown, there was an almost complete emptying out of offices, resulting in an improvement in the sustainability rating of the buildings that housed them and a profound decrease in transport pollution, both public and private, at the disadvantage of a consequent worsening of the sustainability rating of individual buildings in the residential sector.

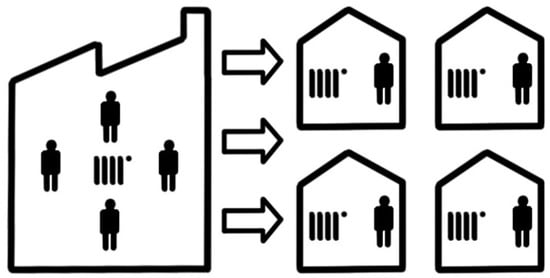

As shown in

Figure 2, in fact, considering that the minimum cubature of a classic office room, e.g., that of a public administration, must be at least 10 cu. m. per employee, multiplying by the number of employees present (4) and dividing by the mandatory minimum height (2.7 m for residential), we obtain approximately 15 sq. m. per employee. This size turns out to be the same as required for the living room (minimum 14 sq. m.) of a residential building [

15,

16]. Assuming for approximation that both rooms (office and living room) have a similar number of radiant elements, it can be assumed that during the periods spent working at home, the energy consumption required to heat the classic office room is no longer shared by the four colleagues but must be multiplied by four, i.e., to heat each individual room, in this case the living room, in which each employee worked. (NB: this is of course only an example estimate, but it is intended to quickly show the effects of the lockdown and the impact on individual homes.)

Figure 2. Diagram of the evolution of energy consumption attributable to 4 employees before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Professionals and workers were not the only ones who had to quickly change their work habits, transforming their homes into private offices from which to interact by video call with colleagues. In many of those home offices, students also had to coexist and find their own space while busy trying to attend classes, study, and interact with their peers through online classes and courses. On the level of

social sustainability, it should be noted that some students, for example, those engaged in the transition from middle school to high school or from high school to university, found themselves interacting for at least a year with colleagues they had never met except in virtual spaces. The future will allow us to understand how much such an event may have affected young minds in the midst of physical, intellectual, and hormonal development and what kind of social side effects it may have caused [

17,

18].

5. Renovations and Energy Efficiency Improvements in the Construction Sector

Once the lockdown period had passed, the slow return to normal occupation of workplaces began, which at the same time had often been subjected to a complete redesign of spaces and a strict separation of internal pathways.

Certainly, if compared regarding the concept of sustainability, the impacts resulting from climate change and that due to COVID-19 appear to be travelling on parallel tracks but at completely different speeds. Compared to the disruptions caused by the pandemic, the impact attributable to climate change appears to have effects on buildings and their users that can be observed more in the long term. In both cases, however, the more or less significant consequences of these impacts will lead to non-negligible changes in the behaviour and perception of re-occupied spaces [

19,

20].

Taking climate emergencies into account during the design phases becomes a fundamental aspect of the new way of conceiving sustainable architecture, and professionals must be an active part of this radical change in perspective. Driven by these motivations, a number of researchers initiated a project to direct students towards these issues even before they became professionals. By working on teaching methods and students, in fact, it is possible to ensure that they, through their academic careers, acquire the appropriate tools to implement the changes in perspective that the AEC sector needs in order to pursue better sustainable architecture [

21].

In the construction sector, the desire or need to converge efforts as much as possible to achieve ever greater levels of sustainability is also dictated by purely economic and practical aspects.

In recent years, both in the Italian and international contexts, the desire to pursue the economic and environmental sustainability of buildings has encouraged the preservation of the existing heritage with respect to possible demolition, reconstruction, or new construction. Renovations aimed at preserving the aforementioned building heritage have the main objective of improving the building’s performance in various aspects, mainly energy.

In Italy, for example, considering only the hospital sector, 85% of healthcare facilities were built before the early 1900s, with the consequent result that 80% of operating theatres today are non-standard in terms of minimum suitability requirements [

22].

The data for the residential sector are no longer comforting. The Italian government, with the aim of restarting the economy and overcoming the problems that had emerged due to the coronavirus, by exploiting the flywheel of sustainability, proposed significant tax breaks for renovation work in the residential building sector with the purpose of improving energy efficiency. In order to obtain these reductions, renovations had to aim for a mandatory improvement of two energy classes of the building compared to the situation at the beginning of the work.

According to the report of the Italian National Agency for New Technologies, Energy, and Sustainable Economic Development (ENEA), as of September 30, 2021, the number of renovations attributable to the

Bonus 110 tax break exceeded 46,000 properties, for a total of EUR 7.5 billion in investments [

23].

Concerning the issues related to the sustainability of the existing building heritage, in 2013 researchers from numerous European universities and research institutions, thanks to the European Union’s Intelligent Energy Europe programme (IEE), began to be concerned and deal with “making transparent and effective energy refurbishment processes in the European housing sector”, first through the cataloguing of building types present in Europe (Project TABULA), which then extended to the “development of building stock models to assess renovation processes and predict future energy consumption”, leading to the drafting of an “agreed set of energy performance indicators that will allow key actors and stakeholders to ensure, at different levels, a high quality of energy renovations, compliance with regulations, to monitor and guide renovation processes in a cost-effective way and to assess the energy savings actually achieved”, the ultimate goal of the EPISCOPE project [

24].

6. COVID-19 and Its Impact on the Global Supply Chain

Environmental sustainability and

economic sustainability, although they both serve the same purpose, due to the different domains in which they operate, may find themselves making choices in opposition to each other. A glaring example, which emerged during the pandemic and has largely persisted up to the present day, is the negative impact of COVID-19 on the global supply chain. This problem has an even more serious impact when materials produced in one country are denied the shortest route to their destination site. This interruption makes it impossible to implement a sustainable supply chain, the ultimate aim of which is to try to reduce greenhouse gas emission levels by designing the fastest link between supply and demand. A link was, indeed, impossible to make during a pandemic with entire nations in lockdown [

25].

Inoltre, i problemi dell’approvvigionamento globale sono estremamente difficili da affrontare, non solo per le nazioni altamente sviluppate ma soprattutto per i piccoli stati in via di sviluppo. All'interno di questa categoria, ad esempio, i Piccoli Stati insulari in via di sviluppo (SIDS), che basano la loro economia esclusivamente sul settore turistico (ad esempio, il PIL delle Seychelles è dovuto per il 67% al turismo), oltre a soffrire gli impatti negativi del cambiamento climatico da anni subiscono drammatici cali del Pil a causa del Covid-19, in media del 7,3%, con punte del 16% per le Maldive e le Seychelles. Inoltre, l’obbligo di far fronte ai disastri causati dal verificarsi sempre più frequente di eventi meteorologici estremi ha minato profondamente la loro già fragile economia, ostacolando la loro capacità di far fronte a ulteriori catastrofi naturali. Nello stesso anno del Covid-19, ad esempio, la pandemia e la quarantena hanno impedito ai SIDS di fornire l’assistenza sanitaria e umanitaria necessaria dopo il ciclone Harold.

La comunità scientifica, attraverso l’International Science Council (ISC), ha istituito un comitato scientifico per sostenere questi piccoli stati già nel 2020, mentre l’Organizzazione per la cooperazione e lo sviluppo economico (OECP) ha avviato studi per mappare le disastrose conseguenze sull’economia le economie di questi stati a causa dell’avvento del COVID-19. Secondo l’ONU, i SIDS si trovano ad affrontare sfide sostanziali in termini di sviluppo sostenibile derivanti dalla pandemia, dal cambiamento climatico e dalle scelte politiche del resto del mondo e necessitano quindi del sostegno urgente – finanziario, tecnico e materiale – da parte dell’intera comunità internazionale, scientifico e non [

26 ,

27 ,

28 ].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/buildings14020482