Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Surgery

Traditionally considered a disease common in the older population, colorectal cancer is increasing in incidence among younger demographics. Evidence suggests that populational- and generational-level shifts in the composition of the human gut microbiome may be tied to the recent trends in gastrointestinal carcinogenesis.

- early-onset colorectal cancer

- EOCRC

- young onset

- adenocarcinoma

- gut microbiome

- inflammation

1. Microbiome and Colorectal Carcinoma

From birth, different population cohorts are exposed to a wide range of different factors that impact their health and risk factors for disease. Individuals born at different time periods and locations have different exposures. Research examining the totality of these exposures for different populations have proposed a framework concept known as exposomes, whereby life-time exposures to different external and internal factors contribute to different risk factors of different birth cohorts [11,12]. This implies that because younger populations have been exposed to a different set of factors by a given age compared to the generation before them at the same age, these factors contribute to a different risk factor profile for different diseases. This may explain why the risk for CRC in the current young population is higher than in generations before. This is inherently different from what has conventionally been considered as a period effect, whereby an event at a particular time and location affects everyone equally [13,14]. The birth-cohort effect suggests that due to the cumulation of different life-time exposures, younger populations have different relative risks for various diseases compared to older generations. When examining the population statistics for different cancers, we find that this is true for CRC. Younger birth-cohorts are at higher risk of CRC compared to older generations at the same age, and these risks theoretically will only accumulate and increase with age.

Previous studies have already found numerous birth-cohort associated life-style factors that are linked with increased rates of CRC, such as diet, sedentary lifestyle, smoking, and alcohol use [2,15,16]. Furthermore, these factors also all appear to directly impact the gut microbiome [17], which is composed of different populations of bacterial, viral, fungal, and protozoan species. The organisms that compose the gut microbiome are cumulatively greater in number than the number of cells in the human body, and could be considered as an “internalized external organ” with an ever more expanding role in the immunity and autoinflammation of the gastrointestinal system [18]. There is an irreplaceable symbiotic relationship between the microbiome and its host. It is required for homeostatic human health, but also contributes to human disease. For example, the gut microbiome is required for the production of vitamins and essential fatty acids not found elsewhere in the body [19]; conversely, pathologic changes in the microbiome are associated with increased inflammation and carcinogenesis [9].

An emerging body of research studies suggests that changes to the host microbiome are intimately tied to early-onset CRC carcinogenesis [20,21]. However, questions of what defines a pro-versus anti-carcinogenic microbiome, and of how a healthy microbiome morphs into a dysbiotic pro-tumorigenic one, remain largely unanswered. More research is needed to understand the mechanisms behind these processes.

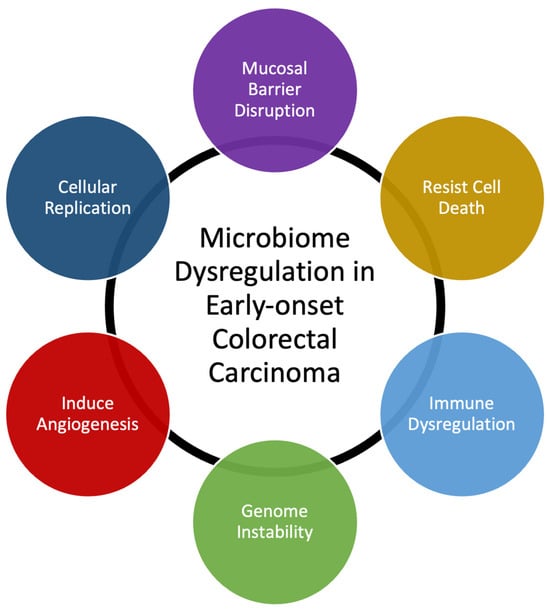

Many bacterial species have been identified as directly responsible for autoinflammation and carcinogenesis [20,22]. Our own data demonstrate that T-cell infiltration and the expression of inflammatory mediators are similar in EOCRC and AOCRC, suggesting that an innate immune response may be requisite to colorectal carcinogenesis in general [21,23]. However, though the presence or absence of individual species may be essential to disease, changes to the composition of the rest of the gut microbial populations also appear to be necessary for its pathogenesis. Here, we provide a generalized overview of possible mechanisms behind how dysbiosis may induce early-onset colorectal carcinoma (Figure 1). Gut microbiome dysbiosis is broadly defined as an imbalance of the microbial ecosystem. At baseline, there are different microbial populations that inhabit different locations of the gastrointestinal tract. These microbial populations interact with each other and the human host. Dysbiosis occurs when the normal homeostatic balance is disrupted. The balance between protective versus harmful microbial communities and metabolism is likely central to understanding where imbalances result in tumorigenesis [24,25].

Figure 1. Summary of mechanisms that microbiome dysregulation may contribute to colorectal carcinogenesis and the increase in early-onset colorectal carcinoma.

Microbial dysbiosis has already been proven to be crucial for many diseases and conditions of the gastrointestinal tract. For example, the sole presence of toxigenic Clostridioides (formerly Clostridium) difficile is not enough for the development of pseudomembranous colitis. In addition to the presence of toxigenic strains, microbial dysbiosis with overpopulation of C. difficile and disruption to other microbial species is required prior to the development of diarrheal symptoms and clinical disease [26,27].

More studies are needed to examine microbiome composition and shifts in microbiome components in response to different external factors: how the microbiome changes to external factors and how these changes drive tumor initiation, progression, and otherwise amplify other cancer risk factors. The connection between dysbiosis of the gut microbiome and the increasing incidence of CRC in young patients appears to have been hypothesized, but concrete evidence of the mechanistic interplay between gut dysbiosis and CRC in younger populations has yet to be published.

The human gut microbiome is composed of a wide range of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa, with up to 1013 to 1014 microorganisms and over 3 million genes, more than the entire human genome. Since the 1960s, it has been known that the carcinogen induction of CRC is intertwined with the microbiome [25]. Experiments with germ-free and conventional rats found that a known CRC carcinogen, cycasin, failed to induce cancer in germ-free rats opposed to conventional strains [28]. Subsequent experiments with other carcinogens found that Escherichia, Enterococcus, Bacteroides, and Clostridium bacteria were responsible for carcinogenesis by increasing the number of aberrant foci caused by the carcinogen 1,2-dimethylhydrazine [29]. The fecal transplant of patients with CRC to mice increased intestinal cell proliferation and tumorigenesis under the influence of carcinogen azoxymethane [30], which suggests that there is a causal relationship between the composition of the gut microbiota and development of CRC under different external stressors [31].

Studies on the gut microbiome in patients with CRC versus healthy individuals without CRC have identified different bacterial compositions between the two populations. When patients are analyzed along the adenoma–carcinoma sequence with metagenome-wide analysis, patients with adenoma demonstrated similar relative deprivations of microbial diversity as healthy individuals. However, patients with advanced CRC demonstrated higher microbiota genes in both absolute number and diversity than the healthy controls and patients with adenoma only [32]. This appears counter to studies analyzing fecal 16S rRNA genes that found patients with CRC had decreased overall microbial diversity via 16S rRNA sequencing, with specific lower relative abundances of specific bacterial species that may be protective against carcinogenesis [33]. This result could be due to technical differences between the studies, as one analyzed fecal 16S rRNA while the other used genome-wide association; however, it could also suggest that the gut microbiome is constantly in flux throughout the CRC developmental process, implying different microbiome compositions at dissimilar stages of disease progression.

Several shotgun metagenomic sequencing analyses have found a core set of colonic bacteria prevalent in patients with CRC and another set of anti-tumorigenic bacteria that are depleted in patients with CRC [34,35,36,37]. Although some common bacterial species have been found to promote CRC, including Bacteroides fragilis [38], Escherichia coli [39], Enterococcus faecalis [40], Streptococcus gallolyticus [41], and Morganella morganii [42], not every single clade in the specified species is carcinogenic. In fact, several of these bacteria are commonly found in the gastrointestinal systems of healthy individuals. In metagenomic analyses, the specific subspecies of the bacteria that cause inflammation and the associated toxigenic genes are not always specified. The mechanisms behind the role of each bacterial clade in carcinogenesis appear to be varied and distinct, but almost all seem to cause an inflammatory response in the enteric mucosal lining. Enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis induces inflammation by producing IL-17 via TH-17 T-cells and γδT-cells [38]. In colitis-susceptible IL-10-deficient mice, the mono-colonization of polyketide synthase-expressing E. coli, which specifically produce colibactin, a polyketide-peptide genotoxin, had increased rates of colorectal malignancy [39]. The depletion of putatively beneficial probiotic bacteria in patients with CRC is less well studied compared to carcinogenic phyla, and the data are more conflicting, but notable species include Streptococcus thermophilus [43,44], several Lactobacillus strains [45,46], Clostridium butyricum [47], and Carnobacterium maltaromaticum [48].

In addition to bacteria, the gut microbiome is also composed of other microorganisms, including viruses [49] and fungi [50], that are altered in patients with CRC, though the data are relatively sparse and occasionally conflicting [31]. Excessive cytomegalovirus, John Cunningham (JC) virus, Epstein–Barr, and human papillomavirus have been identified in human CRC fecal samples [51,52,53]. Increased abundances of Malassezia and other fungi also appear to be associated with CRC [54]. Many of the different microorganism communities crosstalk and influence each other to create dynamic and mutable microbiome, which can contribute to the propagation of CRC [55].

2. Effect of Diet and Environmental Factors on the Microbiome

The influence of environmental extrinsic factors on the gut microbiome and subsequent effects on carcinogenesis remains a field of active investigation (Table 1). Since the early 1900s, it has been established that diet is one of the main contributors to changes in the gut microbiome [56]. The gut microbiome is generally stable over time under conventional circumstances, but significant dietary interventions have also been demonstrated to cause rapid changes over short amounts of time. A metagenomic analysis of fecal samples from 308 male participants without targeted interventions found that between-participant variation was consistently higher than longitudinal changes in the microbiome over 6 months [57]. With dietary intervention, however, targeted qPCR and 16S rRNA sequence analyses found that different bacterial blooms changed within 24–48 h of each intervention, particularly in response to indigestible carbohydrate fibers [58,59]. Longer-term chronic dietary changes in the gut microbiome can even impact the hosts’ offspring with clear generational effects over time. Bacterial populations that decrease after prolonged periods of low carbohydrate diets are not recoverable in several subsequent murine generations even after the reintroduction of the missing carbohydrates, requiring the reintroduction of the lost taxa in addition to replacing the lost dietary carbohydrates [60].

Table 1. Summary of some factors that have been found to influence the composition of the microbiome.

| Factors That Influence the Microbiome | ||

|---|---|---|

| Host Factors | Environmental Factors | Dietary Factors |

| Diabetes | Alcohol | Fiber intake |

| Exercise | Microplastics | Indigestible carbohydrates |

| Genetics | Pesticides | Western diet and red meat |

| Immune health and immunosuppression | Other chemical exposures | Probiotics and fecal transplant |

| Obesity | Smoking | Processed foods |

One of the most prominent representative analyses of differing diets and their impact on disease is the comparison between modern Western diets and rural agrarian diets. Compared to a rural agrarian diet, the microbiome under a Western diet has significantly lower microbial diversity [61]. The modern Western diet appears to increase specific populations of bacteria, which can produce metabolites that form gut microbial exposomes in the host body [62]. The production of N-nitroso compounds and hydrogen sulfide by specific toxigenic bacterial species in nondiverse gut microbiomes exert carcinogenic effects with DNA alkylation and genetic mutations of the gastrointestinal cells [63,64]. Increased rates of CRC development in mice that were fed a Western diet could be attributed to microbial dysbiosis. CRC progression was accelerated after a transplantation of feces from obese to nonobese mice, which could be blocked by continuous treatment with a mix of antibiotics, including ampicillin, vancomycin, neomycin, and metronidazole [65].

In addition to dietary fats and microbial-accessible carbohydrate fibers, the well-demonstrated impact of Western diet on the gut microbiome appears to be also due to a combination of red meat and processed pre-packaged foods. Red meat appears to promote the selective growth of certain bacterial populations through an excessive production of N-nitroso compounds and lipid peroxidation [66]. Ubiquitous in processed foods are emulsifiers that can act like detergents and increase the permeability of the mucosa, increasing bacterial movement across the epithelium and promoting inflammatory bowel disease even at relatively low concentrations [67]. This translocation is counteracted by some soluble plant carbohydrate fibers that inhibit bacterial adhesion and invasion in a dose-dependent manner [68]. The subsequent fermentation of the microbial accessible fiber also produces short-chain fatty acids, which have been demonstrated to regulate intestinal immunity and enhance the CRC treatment response [69]. Although the mechanism causing this phenomenon is largely unclear, it appears to be independent of bacterial growth since the most effective plant fibers seem to selectively enhance the growth of specific bacteria species.

Normally, gut bacteria metabolize dietary indigestible carbohydrates into short-chain fatty acids, such as butyrate, that can be absorbed into the systemic circulation to regulate immune cells [70], epigenetically decrease the rate of proinflammatory cytokine production [71], downregulate integrin to induce the apoptosis of some CRC cancer lines in vitro [72], and suppress carcinogenesis [73]. This process can be disrupted in the presence of many extrinsic factors, such as microplastics, nitrates, pesticides, and other chemicals, which result in disease. At the population level, countries with looser environmental regulations have seen a disproportionate rise in CRC over the last few decades, particularly in local regions with higher rates of pesticide use and/or air pollution [74,75,76]. Other studies have demonstrated increased serum-level pesticide levels in patients with CRC [77] and increased risk of CRC in populations with high exposure to pesticides [78,79]. Even at maximum residue levels tolerated by the European Commission and United States Department of Agriculture, pesticides have been demonstrated to alter the composition of the gut microbiome in both humans and animals [80].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers16030676

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!