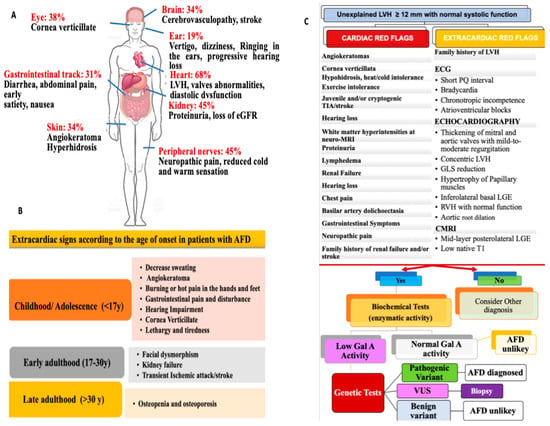

Anderson–Fabry disease (AFD) is a lysosome storage disorder resulting from an X-linked inheritance of a mutation in the galactosidase A (GLA) gene encoding for the enzyme alpha-galactosidase A (α-GAL A). This mutation results in a deficiency or absence of α-GAL A activity, with a progressive intracellular deposition of glycosphingolipids leading to organ dysfunction and failure. Cardiac damage starts early in life, often occurring sub-clinically before overt cardiac symptoms. Left ventricular hypertrophy represents a common cardiac manifestation, albeit conduction system impairment, arrhythmias, and valvular abnormalities may also characterize AFD. Even in consideration of pleiotropic manifestation, diagnosis is often challenging. Thus, knowledge of cardiac and extracardiac diagnostic “red flags” is needed to guide a timely diagnosis.

- Anderson–Fabry disease

- cardiomyopathy

- cardiac involvement

1. Introduction

2. General Features and Clinical Presentation of AFD

3. Cardiac Involvement

3.1. Pathophysiology

3.2. Disease Manifestations: Patient Symptoms

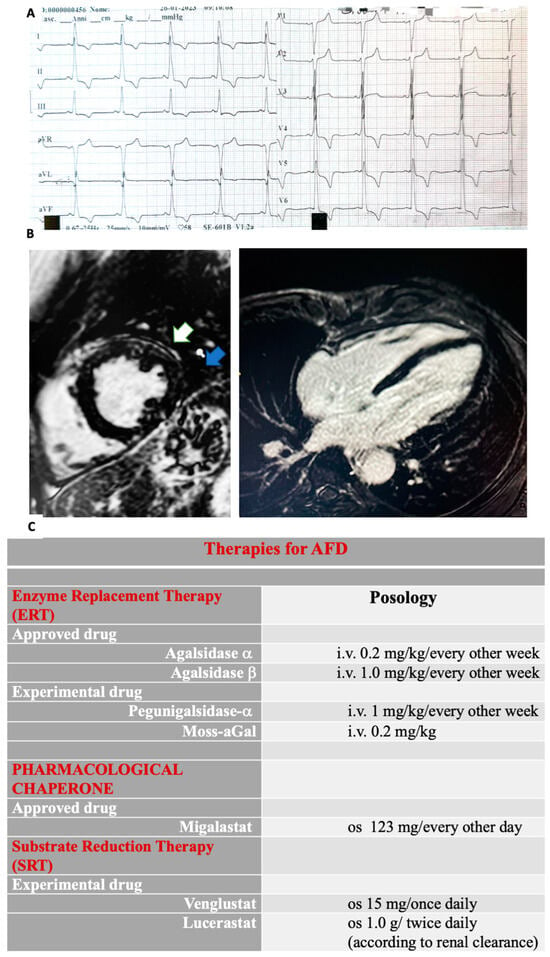

3.2.1. Electrophysiologic Abnormalities and Arrhythmias Burden

3.2.2. Echocardiographic Findings

3.2.3. Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings

4. Diagnostic Workup: The Roles of Genetic and Biochemical Testing, Biopsy, and Biomarkers in AFD

5. Therapy

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/diagnostics14020208

References

- Marian, A.J. Challenges in the diagnosis of anderson-fabry disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 68, 1051–1053.

- Pieroni, M.; Moon, J.C.; Arbustini, E.; Barriales-Villa, R.; Camporeale, A.; Vujkovac, A.C.; Elliott, P.M.; Hagege, A.; Kuusisto, J.; Linhart, A.; et al. Cardiac involvement in fabry disease: Jacc review topic of the week. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2021, 77, 922–936.

- Waldek, S.; Patel, M.R.; Banikazemi, M.; Lemay, R.; Lee, P. Life expectancy and cause of death in males and females with fabry disease: Findings from the fabry registry. Genet. Med. 2009, 11, 790–796.

- Vardarli, I.; Weber, M.; Rischpler, C.; Führer, D.; Herrmann, K.; Weidemann, F. Fabry cardiomyopathy: Current treatment and future options. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2750.

- Ortiz, A.; Abiose, A.; Bichet, D.G.; Cabrera, G.; Charrow, J.; Germain, D.P.; Hopkin, R.J.; Jovanovic, A.; Linhart, A.; Maruti, S.S.; et al. Time to treatment benefit for adult patients with fabry disease receiving agalsidase β: Data from the fabry registry. J. Med. Genet. 2016, 53, 495–502.

- Ortiz, A.; Germain, D.P.; Desnick, R.J.; Politei, J.; Mauer, M.; Burlina, A.; Eng, C.; Hopkin, R.J.; Laney, D.; Linhart, A.; et al. Fabry disease revisited: Management and treatment recommendations for adult patients. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2018, 123, 416–427.

- Citro, R.; Prota, C.; Ferraioli, D.; Iuliano, G.; Bellino, M.; Radano, I.; Silverio, A.; Migliarino, S.; Polito, M.V.; Ruggiero, A.; et al. Importance of echocardiography and clinical “red flags” in guiding genetic screening for fabry disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 838200.

- Baig, S.; Edward, N.C.; Kotecha, D.; Liu, B.; Nordin, S.; Kozor, R.; Moon, J.C.; Geberhiwot, T.; Steeds, R.P. Ventricular arrhythmia and sudden cardiac death in fabry disease: A systematic review of risk factors in clinical practice. Europace 2018, 20, f153–f161.

- Meikle, P.J.; Hopwood, J.J.; Clague, A.E.; Carey, W.F. Prevalence of lysosomal storage disorders. Jama 1999, 281, 249–254.

- Inoue, T.; Hattori, K.; Ihara, K.; Ishii, A.; Nakamura, K.; Hirose, S. Newborn screening for fabry disease in japan: Prevalence and genotypes of fabry disease in a pilot study. J. Hum. Genet. 2013, 58, 548–552.

- Spada, M.; Pagliardini, S.; Yasuda, M.; Tukel, T.; Thiagarajan, G.; Sakuraba, H.; Ponzone, A.; Desnick, R.J. High incidence of later-onset fabry disease revealed by newborn screening. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2006, 79, 31–40.

- Wozniak, M.A.; Kittner, S.J.; Tuhrim, S.; Cole, J.W.; Stern, B.; Dobbins, M.; Grace, M.E.; Nazarenko, I.; Dobrovolny, R.; McDade, E.; et al. Frequency of unrecognized fabry disease among young european-american and african-american men with first ischemic stroke. Stroke 2010, 41, 78–81.

- Linhart, A.; Elliott, P.M. The heart in anderson-fabry disease and other lysosomal storage disorders. Heart 2007, 93, 528–535.

- Favalli, V.; Disabella, E.; Molinaro, M.; Tagliani, M.; Scarabotto, A.; Serio, A.; Grasso, M.; Narula, N.; Giorgianni, C.; Caspani, C.; et al. Genetic screening of anderson-fabry disease in probands referred from multispecialty clinics. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016, 68, 1037–1050.

- Zarate, Y.A.; Hopkin, R.J. Fabry’s disease. Lancet 2008, 372, 1427–1435.

- Mehta, A.; Clarke, J.T.; Giugliani, R.; Elliott, P.; Linhart, A.; Beck, M.; Sunder-Plassmann, G. Natural course of fabry disease: Changing pattern of causes of death in fos—fabry outcome survey. J. Med. Genet. 2009, 46, 548–552.

- Patel, V.; O’Mahony, C.; Hughes, D.; Rahman, M.S.; Coats, C.; Murphy, E.; Lachmann, R.; Mehta, A.; Elliott, P.M. Clinical and genetic predictors of major cardiac events in patients with anderson-fabry disease. Heart 2015, 101, 961–966.

- Akhtar, M.M.; Elliott, P.M. Anderson-fabry disease in heart failure. Biophys. Rev. 2018, 10, 1107–1119.

- Nakao, S.; Takenaka, T.; Maeda, M.; Kodama, C.; Tanaka, A.; Tahara, M.; Yoshida, A.; Kuriyama, M.; Hayashibe, H.; Sakuraba, H.; et al. An atypical variant of fabry’s disease in men with left ventricular hypertrophy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995, 333, 288–293.

- von Scheidt, W.; Eng, C.M.; Fitzmaurice, T.F.; Erdmann, E.; Hübner, G.; Olsen, E.G.; Christomanou, H.; Kandolf, R.; Bishop, D.F.; Desnick, R.J. An atypical variant of fabry’s disease with manifestations confined to the myocardium. N. Engl. J. Med. 1991, 324, 395–399.

- Echevarria, L.; Benistan, K.; Toussaint, A.; Dubourg, O.; Hagege, A.A.; Eladari, D.; Jabbour, F.; Beldjord, C.; De Mazancourt, P.; Germain, D.P. X-chromosome inactivation in female patients with fabry disease. Clin. Genet. 2016, 89, 44–54.

- Vitale, G.; Ditaranto, R.; Graziani, F.; Tanini, I.; Camporeale, A.; Lillo, R.; Rubino, M.; Panaioli, E.; Di Nicola, F.; Ferrara, V.; et al. Standard ecg for differential diagnosis between anderson-fabry disease and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Heart 2022, 108, 54–60.

- Doheny, D.; Srinivasan, R.; Pagant, S.; Chen, B.; Yasuda, M.; Desnick, R.J. Fabry disease: Prevalence of affected males and heterozygotes with pathogenic gla mutations identified by screening renal, cardiac and stroke clinics, 1995–2017. J Med Genet 2018, 55, 261–268.

- Stankowski, K.; Figliozzi, S.; Battaglia, V.; Catapano, F.; Francone, M.; Monti, L. Fabry disease: More than a phenocopy of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7061.

- Militaru, S.; Jurcuț, R.; Adam, R.; Roşca, M.; Ginghina, C.; Popescu, B.A. Echocardiographic features of fabry cardiomyopathy-comparison with hypertrophy-matched sarcomeric hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Echocardiography 2019, 36, 2041–2049.

- Karur, G.R.; Robison, S.; Iwanochko, R.M.; Morel, C.F.; Crean, A.M.; Thavendiranathan, P.; Nguyen, E.T.; Mathur, S.; Wasim, S.; Hanneman, K. Use of myocardial t1 mapping at 3.0 t to differentiate anderson-fabry disease from hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Radiology 2018, 288, 398–406.

- Wechalekar, A.D.; Fontana, M.; Quarta, C.C.; Liedtke, M. Al amyloidosis for cardiologists: Awareness, diagnosis, and future prospects: Jacc: Cardiooncology state-of-the-art review. JACC CardioOncol 2022, 4, 427–441.

- Azevedo, O.; Cordeiro, F.; Gago, M.F.; Miltenberger-Miltenyi, G.; Ferreira, C.; Sousa, N.; Cunha, D. Fabry disease and the heart: A comprehensive review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4434.

- Frustaci, A.; Morgante, E.; Russo, M.A.; Scopelliti, F.; Grande, C.; Verardo, R.; Franciosa, P.; Chimenti, C. Pathology and function of conduction tissue in fabry disease cardiomyopathy. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2015, 8, 799–805.

- Ikari, Y.; Kuwako, K.; Yamaguchi, T. Fabry’s disease with complete atrioventricular block: Histological evidence of involvement of the conduction system. Br. Heart J. 1992, 68, 323–325.

- Mehta, A.; Ricci, R.; Widmer, U.; Dehout, F.; Garcia de Lorenzo, A.; Kampmann, C.; Linhart, A.; Sunder-Plassmann, G.; Ries, M.; Beck, M. Fabry disease defined: Baseline clinical manifestations of 366 patients in the fabry outcome survey. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2004, 34, 236–242.

- Linhart, A.; Kampmann, C.; Zamorano, J.L.; Sunder-Plassmann, G.; Beck, M.; Mehta, A.; Elliott, P.M. Cardiac manifestations of anderson-fabry disease: Results from the international fabry outcome survey. Eur. Heart J. 2007, 28, 1228–1235.

- Wu, J.C.; Ho, C.Y.; Skali, H.; Abichandani, R.; Wilcox, W.R.; Banikazemi, M.; Packman, S.; Sims, K.; Solomon, S.D. Cardiovascular manifestations of fabry disease: Relationships between left ventricular hypertrophy, disease severity, and alpha-galactosidase a activity. Eur. Heart J. 2010, 31, 1088–1097.

- Selthofer-Relatic, K. Time of anderson-fabry disease detection and cardiovascular presentation. Case Rep. Cardiol. 2018, 2018, 6131083.

- Clarke, J.T.; Giugliani, R.; Sunder-Plassmann, G.; Elliott, P.M.; Pintos-Morell, G.; Hernberg-Ståhl, E.; Malmenäs, M.; Beck, M. Impact of measures to enhance the value of observational surveys in rare diseases: The fabry outcome survey (fos). Value Health 2011, 14, 862–866.

- Eng, C.M.; Fletcher, J.; Wilcox, W.R.; Waldek, S.; Scott, C.R.; Sillence, D.O.; Breunig, F.; Charrow, J.; Germain, D.P.; Nicholls, K.; et al. Fabry disease: Baseline medical characteristics of a cohort of 1765 males and females in the fabry registry. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2007, 30, 184–192.

- Namdar, M. Electrocardiographic changes and arrhythmia in fabry disease. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2016, 3, 7.

- Kampmann, C.; Wiethoff, C.M.; Whybra, C.; Baehner, F.A.; Mengel, E.; Beck, M. Cardiac manifestations of anderson-fabry disease in children and adolescents. Acta Paediatr. 2008, 97, 463–469.

- Rapezzi, C.; Arbustini, E.; Caforio, A.L.; Charron, P.; Gimeno-Blanes, J.; Heliö, T.; Linhart, A.; Mogensen, J.; Pinto, Y.; Ristic, A.; et al. Diagnostic work-up in cardiomyopathies: Bridging the gap between clinical phenotypes and final diagnosis. A position statement from the esc working group on myocardial and pericardial diseases. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 34, 1448–1458.

- Namdar, M.; Steffel, J.; Vidovic, M.; Brunckhorst, C.B.; Holzmeister, J.; Lüscher, T.F.; Jenni, R.; Duru, F. Electrocardiographic changes in early recognition of fabry disease. Heart 2011, 97, 485–490.

- Yeung, D.F.; Sirrs, S.; Tsang, M.Y.C.; Gin, K.; Luong, C.; Jue, J.; Nair, P.; Lee, P.K.; Tsang, T.S.M. Echocardiographic assessment of patients with fabry disease. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2018, 31, 639–649.e632.

- Tower-Rader, A.; Jaber, W.A. Multimodality imaging assessment of fabry disease. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2019, 12, e009013.

- Chimenti, C.; Russo, M.A.; Frustaci, A. Atrial biopsy evidence of fabry disease causing lone atrial fibrillation. Heart 2010, 96, 1782–1783.

- Linhart, A.; Palecek, T.; Bultas, J.; Ferguson, J.J.; Hrudová, J.; Karetová, D.; Zeman, J.; Ledvinová, J.; Poupetová, H.; Elleder, M.; et al. New insights in cardiac structural changes in patients with fabry’s disease. Am. Heart J. 2000, 139, 1101–1108.

- Sachdev, B.; Takenaka, T.; Teraguchi, H.; Tei, C.; Lee, P.; McKenna, W.J.; Elliott, P.M. Prevalence of anderson-fabry disease in male patients with late onset hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2002, 105, 1407–1411.

- Calcagnino, M.; O’Mahony, C.; Coats, C.; Cardona, M.; Garcia, A.; Janagarajan, K.; Mehta, A.; Hughes, D.; Murphy, E.; Lachmann, R.; et al. Exercise-induced left ventricular outflow tract obstruction in symptomatic patients with anderson-fabry disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2011, 58, 88–89.

- Mehta, A.; Beck, M.; Sunder-Plassmann, G. Fabry Disease: Perspectives from 5 Years of FOS; Oxford PharmaGenesis: Oxford, UK, 2006.

- Weidemann, F.; Breunig, F.; Beer, M.; Sandstede, J.; Störk, S.; Voelker, W.; Ertl, G.; Knoll, A.; Wanner, C.; Strotmann, J.M. The variation of morphological and functional cardiac manifestation in fabry disease: Potential implications for the time course of the disease. Eur. Heart J. 2005, 26, 1221–1227.

- Deva, D.P.; Hanneman, K.; Li, Q.; Ng, M.Y.; Wasim, S.; Morel, C.; Iwanochko, R.M.; Thavendiranathan, P.; Crean, A.M. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance demonstration of the spectrum of morphological phenotypes and patterns of myocardial scarring in anderson-fabry disease. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2016, 18, 14.

- Weidemann, F.; Sommer, C.; Duning, T.; Lanzl, I.; Möhrenschlager, M.; Naleschinski, D.; Arning, K.; Baron, R.; Niemann, M.; Breunig, F.; et al. Department-related tasks and organ-targeted therapy in fabry disease: An interdisciplinary challenge. Am. J. Med. 2010, 123, e651–e658.

- Messroghli, D.R.; Moon, J.C.; Ferreira, V.M.; Grosse-Wortmann, L.; He, T.; Kellman, P.; Mascherbauer, J.; Nezafat, R.; Salerno, M.; Schelbert, E.B.; et al. Clinical recommendations for cardiovascular magnetic resonance mapping of t1, t2, t2* and extracellular volume: A consensus statement by the society for cardiovascular magnetic resonance (SCMR) endorsed by the european association for cardiovascular imaging (EACVI). J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 2017, 19, 75.

- Schelbert, E.B.; Messroghli, D.R. State of the art: Clinical applications of cardiac t1 mapping. Radiology 2016, 278, 658–676.

- Augusto, J.B.; Johner, N.; Shah, D.; Nordin, S.; Knott, K.D.; Rosmini, S.; Lau, C.; Alfarih, M.; Hughes, R.; Seraphim, A.; et al. The myocardial phenotype of fabry disease pre-hypertrophy and pre-detectable storage. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2021, 22, 790–799.

- Ho, C.Y.; Abbasi, S.A.; Neilan, T.G.; Shah, R.V.; Chen, Y.; Heydari, B.; Cirino, A.L.; Lakdawala, N.K.; Orav, E.J.; González, A.; et al. T1 measurements identify extracellular volume expansion in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy sarcomere mutation carriers with and without left ventricular hypertrophy. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2013, 6, 415–422.

- Germain, D.P. Fabry disease. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2010, 5, 30.

- Eng, C.M.; Guffon, N.; Wilcox, W.R.; Germain, D.P.; Lee, P.; Waldek, S.; Caplan, L.; Linthorst, G.E.; Desnick, R.J. Safety and efficacy of recombinant human alpha-galactosidase a replacement therapy in fabry’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 9–16.

- Schiffmann, R.; Kopp, J.B.; Austin, H.A., 3rd; Sabnis, S.; Moore, D.F.; Weibel, T.; Balow, J.E.; Brady, R.O. Enzyme replacement therapy in fabry disease: A randomized controlled trial. Jama 2001, 285, 2743–2749.

- Germain, D.P.; Hughes, D.A.; Nicholls, K.; Bichet, D.G.; Giugliani, R.; Wilcox, W.R.; Feliciani, C.; Shankar, S.P.; Ezgu, F.; Amartino, H.; et al. Treatment of fabry’s disease with the pharmacologic chaperone migalastat. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016, 375, 545–555.

- Benjamin, E.R.; Della Valle, M.C.; Wu, X.; Katz, E.; Pruthi, F.; Bond, S.; Bronfin, B.; Williams, H.; Yu, J.; Bichet, D.G.; et al. The validation of pharmacogenetics for the identification of fabry patients to be treated with migalastat. Genet. Med. 2017, 19, 430–438.

- Schiffmann, R.; Murray, G.J.; Treco, D.; Daniel, P.; Sellos-Moura, M.; Myers, M.; Quirk, J.M.; Zirzow, G.C.; Borowski, M.; Loveday, K.; et al. Infusion of alpha-galactosidase a reduces tissue globotriaosylceramide storage in patients with fabry disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 365–370.

- Spinelli, L.; Pisani, A.; Sabbatini, M.; Petretta, M.; Andreucci, M.V.; Procaccini, D.; Lo Surdo, N.; Federico, S.; Cianciaruso, B. Enzyme replacement therapy with agalsidase beta improves cardiac involvement in fabry’s disease. Clin. Genet. 2004, 66, 158–165.

- Parenti, G.; Moracci, M.; Fecarotta, S.; Andria, G. Pharmacological chaperone therapy for lysosomal storage diseases. Future Med. Chem. 2014, 6, 1031–1045.

- Hughes, D.A.; Nicholls, K.; Shankar, S.P.; Sunder-Plassmann, G.; Koeller, D.; Nedd, K.; Vockley, G.; Hamazaki, T.; Lachmann, R.; Ohashi, T.; et al. Oral pharmacological chaperone migalastat compared with enzyme replacement therapy in fabry disease: 18-month results from the randomised phase iii attract study. J. Med. Genet. 2017, 54, 288–296.

- Lenders, M.; Nordbeck, P.; Kurschat, C.; Eveslage, M.; Karabul, N.; Kaufeld, J.; Hennermann, J.B.; Patten, M.; Cybulla, M.; Müntze, J.; et al. Treatment of fabry disease management with migalastat-outcome from a prospective 24 months observational multicenter study (famous). Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2022, 8, 272–281.

- Narita, I.; Ohashi, T.; Sakai, N.; Hamazaki, T.; Skuban, N.; Castelli, J.P.; Lagast, H.; Barth, J.A. Efficacy and safety of migalastat in a japanese population: A subgroup analysis of the attract study. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2020, 24, 157–166.

- Lenders, M.; Nordbeck, P.; Kurschat, C.; Karabul, N.; Kaufeld, J.; Hennermann, J.B.; Patten, M.; Cybulla, M.; Müntze, J.; Üçeyler, N.; et al. Treatment of fabry’s disease with migalastat: Outcome from a prospective observational multicenter study (famous). Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 108, 326–337.

- Feldt-Rasmussen, U.; Hughes, D.; Sunder-Plassmann, G.; Shankar, S.; Nedd, K.; Olivotto, I.; Ortiz, D.; Ohashi, T.; Hamazaki, T.; Skuban, N.; et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of migalastat treatment in fabry disease: 30-month results from the open-label extension of the randomized, phase 3 attract study. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2020, 131, 219–228.

- Germain, D.P.; Nicholls, K.; Giugliani, R.; Bichet, D.G.; Hughes, D.A.; Barisoni, L.M.; Colvin, R.B.; Jennette, J.C.; Skuban, N.; Castelli, J.P.; et al. Efficacy of the pharmacologic chaperone migalastat in a subset of male patients with the classic phenotype of fabry disease and migalastat-amenable variants: Data from the phase 3 randomized, multicenter, double-blind clinical trial and extension study. Genet. Med. 2019, 21, 1987–1997.