Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Archaeology

The Berber and Arab conquest of the Iberian Peninsula in 711 C.E. led to a profound transformation of the agricultural landscape. The layout of the irrigated areas, both rural and urban, is recognisable because it is the result of social and technological choices. But irrigated agriculture was not the only option in Al-Andalus.

- Al-Andalus

- irrigation

- dry farming

1. Introduction

The Berber and Arab conquest of the Iberian Peninsula in 711 C.E. led to a profound transformation of the agricultural landscape. This was largely linked to the creation of irrigation systems and was particularly important in the eastern Iberian Peninsula, the Balearic Islands, and eastern Andalusia. The ecological conditions were favourable for the development of both small rural irrigated areas and huertas—large, irrigated areas usually associated with urban centres.

Much of the research conducted on irrigated areas in Andalusia is owed to the work of several pioneering authors; Thomas Glick’s research on the huerta of Valencia brought to light the existence of management techniques not directed by the state but rather local communities [1]. Pierre Guichard and André Bazzana [2] identified a link between Andalusi rural hydraulics and the settlement of Berber and Arab tribes in šarq al-Andalus (eastern Iberian Peninsula). Their proposal was based on the studies of Pierre Guichard [3], who identified the migration of Arab and Berber groups to the Iberian Peninsula and described the tribal organization of the Andalusi society. Miquel Barceló’s identification of rural peasant hydraulics challenged both the association of the new agriculture with the state and the supposed Roman origin of the huertas of the eastern Iberian Peninsula [4,5].

The initial attempts to study Andalusi hydraulics and irrigation were soon deeply influenced by Andrew M. Watson [6,7]. For Watson, the introduction of new plants of tropical origin into the Mediterranean agricultural cycle through irrigation made it possible to achieve greater crop diversification. This diversification and intensification brought greater and more substantial benefits to the area, which, in turn, led to population growth and urbanisation. Finally, the existence of a strong, centralised state would lead to the creation of a culturally homogeneous world—that of Dar-al-Islam—which would become the medium for the circulation of ideas, products, plants, and agricultural techniques. The role of elites as agents of diffusion would have therefore been essential. However, this view relies on the information provided by written documentation, which, in turn, is heavily biased by the perspective of the state. According to A. Watson, it was the combination of these processes that produced an agricultural revolution. This revolution cannot be understood as an abrupt change, but as a complex process that would gradually shape a “new agriculture” integrated into a “new network of exchanges” that would no longer resemble pre-Islamic agriculture.

Regarding new vegetables, our evidence is again based almost exclusively on the written record, such as the agricultural treaties, several references in historical or geographical Andalusi writings, and documents from the period immediately following the Christian conquest. In addition to the research carried out by A. Watson, it is worth noting the research done by other authors is also based mainly on Andalusi agronomic treatises [8,9,10]. See also the detailed compilation of species mentioned in agronomic works [11,12]. Regarding the information that can be obtained from the documentation generated after the feudal conquests, see [13,14]. This limitation makes it difficult to trace the actual spread of different plants, the local circumstances, and their chronology. Although Watson has been criticised, and some of the eighteen plants he studied may have been known and cultivated before the Islamic expansion (at least in the Middle East) [15,16], archaeology has not yet explored this question in sufficient depth [17]. Bioarchaeological techniques have been occasionally applied to Andalusi sites [18]. Successful results in this field depend on good preservation conditions. Therefore, the botanical macro-remains usually obtained by flotation or the sieving of sediments are not necessarily representative of the entire set of crops cultivated, but rather only of those that have been well-preserved by carbonization, mineralization, or exceptionally in waterlogged conditions. Under these conditions, the remains that are best preserved are those of cereals, legumes, and some stone fruits [19]. Although these findings are not representative of the plant diffusion from the 8th century onwards, some trends are being identified. At least two new species, pearl millet and rice, have been identified. Rice was among the crops mentioned by Watson [7], but pearl millet is a completely new find, especially well-spread and with textual references in the east of the Peninsula. Among fruits, apricots, quince, medlar, and citrus appear for the first time in Islamic sites [19].

The relationship established by Watson between population growth, the development of cities, commercial exchanges, and the state agency, on the one hand, and the diffusion of plants and hydraulic techniques of oriental origin, on the other hand, has been widely accepted, at least in the historiography of Al-Andalus. Various authors link the creation of urban irrigated areas (huertas) and the diffusion of techniques and plants with the consolidation of the Caliphate of Córdoba in the 10th century and the growth of the cities [20,21]. So, a long transitional period was characterised by the so-called “Islamisation” process [22,23,24] that had to be completed before the typical features of an Islamic society could be recognised and, according to these authors, state, religion, and urban development were the main drivers of the transformation of the agrarian landscape. Recently, Pedro Jiménez-Castillo and Inmaculada Camarero [25] have suggested that the emergence of geoponic books in the 11th century is closely related to the proliferation of private landowners in the growing cities of Al-Andalus. These landowners would have developed commercial agriculture.

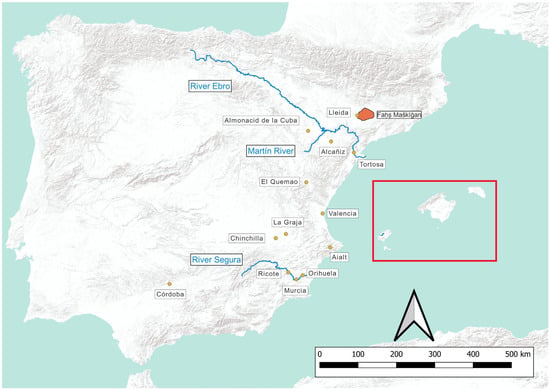

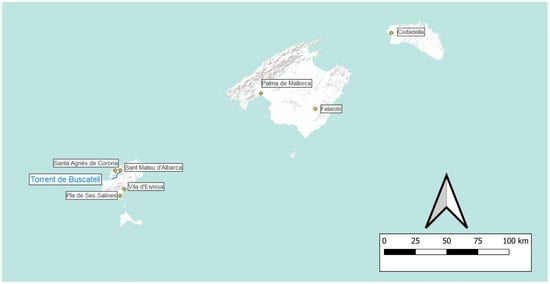

On the other hand, other authors, following the approach of Miquel Barceló, have carried out extensive research on cultivation areas linked to networks of peasant settlements [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33] and, more recently, on urban irrigated areas [34,35,36,37,38], which have demonstrated the capacity of immigrant peasant groups to create and manage a new agricultural landscape (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Fèlix Retamero [39] warned that the codification of techniques in agronomic treatises presents a biased view of technical and plant-based dissemination conducted by state and urban environments. He instead proposes that the success of the transfer of plants and techniques, especially irrigation, required a network of peasant settlements, where the conditions for the transmission of the agricultural technical package were developed.

Figure 1. Location of cited sites in the Iberian Peninsula. Red square: see Figure 2.

Figure 2. Location of cited sites in the Balearic Islands.

2. Irrigation in Al-Andalus

Although it is indeed difficult to obtain absolute dates for the creation of these cultivated areas, the Arab and Berber migration that accompanied the Islamic conquest provides a plausible context. This does not preclude later creation and enlargement of irrigated areas. Most of the available chronologies rely on the association between the toponymy, the archaeological sites, and the irrigated areas, as well as references in written records that usually only establish a terminus ante quem. This procedure is not as precise as would be desirable, but it has been and still is the best and only way to establish chronologies of the field systems studied and, in any case, this type of study is essential to addressing the new dating techniques such as OSL that are increasingly being tested in fields and terraces [40,41].

The lack of chronological precision also affects the assumption of a later creation. The authors who defend the later creation of irrigated cultivation spaces usually base this on the same criteria, but they identify textual mentions with the initial moment of construction, and this cannot always be justified [20,21]. First, textual mentions typically only confirm the existence of a specific irrigated area at a certain time but not the date of its construction. Furthermore, mentions in Arabic texts are not only scarce but mostly refer only to urban spaces without detailed descriptions. Therefore, it is difficult to ascertain irrigated surfaces, or if there was more than one phase of construction.

Attempts at the absolute dating of plots within well-studied irrigated systems of Al-Andalus have been limited to two cases: one in Tortosa (Catalonia) and another in Ricote (Murcia). The first cultivated area has been dated between the 8th and 9th centuries in Tortosa [42], and between the 10th and 13th centuries in Ricote [43]. In a previous article, the dating of the irrigated area of Ricote was attributed to the 9th century [44]. Much more dating of field systems is needed to be representative.

Regarding the species cultivated in the irrigated areas, it is still extremely difficult to know the cultivation regime and the combinations of plants. There is scattered documentary evidence related to specific sites, mostly recorded in Christian documents written immediately after the conquest [13,14] or by a few Arab chroniclers or geographers [45]. Not only the specific species but also the combination of plants, cultivation regimes, and field systems are relevant to determine whether there were changes in the landscape and agriculture because of the Islamic conquest. In this sense, research into field systems is of great importance.

When we think of the hydraulic techniques that spread throughout the Iberian Peninsula, we usually think of water collection techniques such as qanāt(s) and water-lifting devices, or water mills with vertical penstocks [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. Some authors have gone to great efforts to demonstrate the Roman origin and the diffusion of these hydraulic techniques [47,48,49,50] that, moreover, were already intensively used in Sassanian Mesopotamia [51].

However, the use of these techniques in Roman agriculture is known in a very fragmentary way. What is relevant is not the mere fact of knowing a technique existed, but rather how it was used and its relation to the hydraulic system in which it is included. From what little we know about Roman hydraulics applied to agriculture, the selection of techniques and spaces and the organization of the hydraulic complexes are governed by very different criteria. Roman hydraulic structures and their remains were rarely reused in the construction of Andalusi irrigated spaces [52]. An example of reuse is the Roman dam of Almonacid de la Cuba (Zaragoza). However, it was used as a means of water derivation and no longer as a reservoir because it was filled with sediment [53]. Thus, the discovery of the Lex Rivi Hiberiensis is indicative of an irrigated fluvial space near the Ebro River and an organization of the distribution of water [50,51,52,53,54], but it does not provide information about the continuity of either the space or its management, nor does it justify the inability to build new hydraulic systems in the Middle Ages. Nevertheless, the spatial association between irrigated areas and the archaeological sites near the Martín River (from the 6th and 7th centuries) and in the area of La Redehuerta, in the valley of the Guadalupe River (Alcañiz), (from the 4th and 5th centuries) made it possible to suggest that the irrigation in the bottom of these valleys predates the Islamic conquest [55,56].

Research on peasant settlements in Al-Andalus has made it possible to establish a typology of hydraulic systems based on whether they were built on a terraced slope or the bottom of a valley. The location of the water catchment on the valley floor or the slope also determines different morphological solutions [33]. In general, the irrigated space is near the water catchment. The choice of where to build the fields is determined by the location of the water catchment. For this reason, there are usually no long canals in peasant-irrigated areas, and the residence areas usually are not coincident with Roman or late antique ones. These technological choices show that even though some hydraulic techniques may have been known before the Islamic conquest, the creation of irrigated areas is indeed the result of new selections.

The criteria for the construction of these spaces are not only technical. The preference for small sizes is likely in response to risk minimisation strategies, population growth, and segmentation processes [57,58]. The average size of the rural irrigated areas is 1.2 ha, and a scale of sizes of irrigated areas associated with rural settlements has been set: small areas are those with a maximum size of 1 ha (56.6%), medium-sized areas measure between 1.1 and 2 ha (18%), and large areas are those between 2 and 15 ha (21%) [31]. These sizes leave little room for individual forms of ownership and require cooperative mechanisms for their construction and management. Areas larger than 2 ha were often shared by several settlements while conversely, those less than 2 ha rarely allowed for shared management and seem to be associated with a single peasant group [58]. It is also possible to describe peasant strategies for the organization of grinding through hydraulic mills inserted in the water circuit, which aim to ensure compatibility with irrigation operations while diversifying grinding occasions [59]. Regional studies in the Balearic Islands have shown that these cultivation areas and the associated residential areas form settlement networks with collective or negotiated management of hunting and gathering territories [26,27,28,29,32,60].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/agronomy14010196

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!