Rural development is a problem of social and economic nature, which is required to be addressed in a manner taking into account its complexity. This development is related to planning and policy actions which central problem is (Ackoff 1977) how to make the proposed planning solutions accepted and implemented effectively. In rural context, this means to deal with a set of stakeholders with different education levels, purposes and influences, and with a set of standards which is lower than that of urban or national development.

- rural development

- public policy

- social improvement

- inclusive growth

- policy relationship

- hierarchical representation

1. Introduction

2. The Vectors of Rural Development

-

Individual financial levers, like the access to financial resources, subsidies, specific loans, banking strategies and other financing possibilities for individual to develop rural activities (Reddy 2010; Tabares et al. 2022).

-

Family socio-economic improvement, i.e., other economic actions to increase the individual and familial wealth, like employment creation, support to family income or economic improvement of familial units (Briones 2013; Kvist 2020).

-

Individual health and nutrition (World Health Organization 1961), like food assistance programs, increasing of individual health follow-up or giving basic and enabling health conditions to individuals and families (Lawson 1993; Gonzalez-Feliu et al. 2018).

-

Education and training (Maldonado-Mariscal and Alijew 2023), in terms of access to basic education at both the elementary/high school (Lawson 1993) and university level (Umpleby and Shandruk 2013), as well as of specific education and training programs for local rural populations (Collett and Gale 2009).

-

Community enabling and social cohesion (Shucksmith and Chapman 1998), which aim to develop the community and increase the links between their members (Hart et al. 2014).

-

Cultural issues (McCann 2002), aiming at maintaining and developing the culture specificities of rural communities.

-

Agricultural resource improvement, i.e., increasing access to fields, water, crops and other land and water resources necessary for agriculture.

-

Political drivers (Giessen 2010), i.e., policy and political actions and levers that support the development of a territory, such as relationships between local and national politics, the development of laws, or collaborative policy-making forums, among others.

-

Other issues not included above, like coordination among stakeholders (Reina-Usuga et al. 2012), communication (Meyer 2003) or participation issues (Oakley and Marsden 1984), among others.

-

Primary economic improvement, aiming at increasing the financial and socio-economic capabilities of individuals and families.

-

Cost reduction to increase nutrition and health accessibility, in order to improve individual and family health conditions and improve their socio-economic conditions.

-

Food access initiatives, as well as health access initiatives, giving the possibility to families of improving their health and nutrition by directly providing part of their needs instead of economic support.

-

Education, training, and monitoring programs or education access initiatives, to improve individuals’ competencies. These could be completed by work access initiatives that would both improve competencies and wealth.

-

Promotion and development of self-production for food autonomy, which is aimed mainly to support health and nutrition but can have an impact on competencies and socio-economic improvement.

3. Public policy actions in rural development: a typology

Public policies for rural development can be of different nature and, as seen above, are related to various drivers and levers. According to various authors (refs.) those policies can be groupes into 5 well-defined categories:

- Economic policies are those that bring wealth and improve the economic conditions of rural populations. They are mainly related to the access and formalization to land and/or real estate accession, employment creation and improvement, access to financial instruments, productivity improvement and technological evolutions, among others.

- Environmental policies are those related to the access to resources. If access to land (seen as access to property in the context of real estate actions) is considered an economic policy, the access to crops and agricultural resources, water and the promotion of biodiversity and fertility of land are considered environmental. It is important to note that not all environmental policies are incompatible with economic ones, and sometimes there are strong synergies between them.

- Social policies, related to the improvement of communities as a society and their individual and collective competencies. Researchers find in this category education, health, mobility, peace and cohabitation issues.

- Cultural policies differ from social ones in the fact that they promote the characteristics and identity of the rural areas. They are more relate to the construction and defense of a common construct (called culture) that is evolutive, goes beyond traditions, and defines a rural community. Researchers find in this category policies like demographic dynamics, identity issues, the relationships between rural and urban areas or those between communities, or the promotion of languages or cultural heritages, among others.

- Political and participation policies allow the community and its individuals to propose, participate and communicate with decision makers. They are the basis of public-private cooperation and are mainly related to consensus searching, communication and participation in the decision making processes.

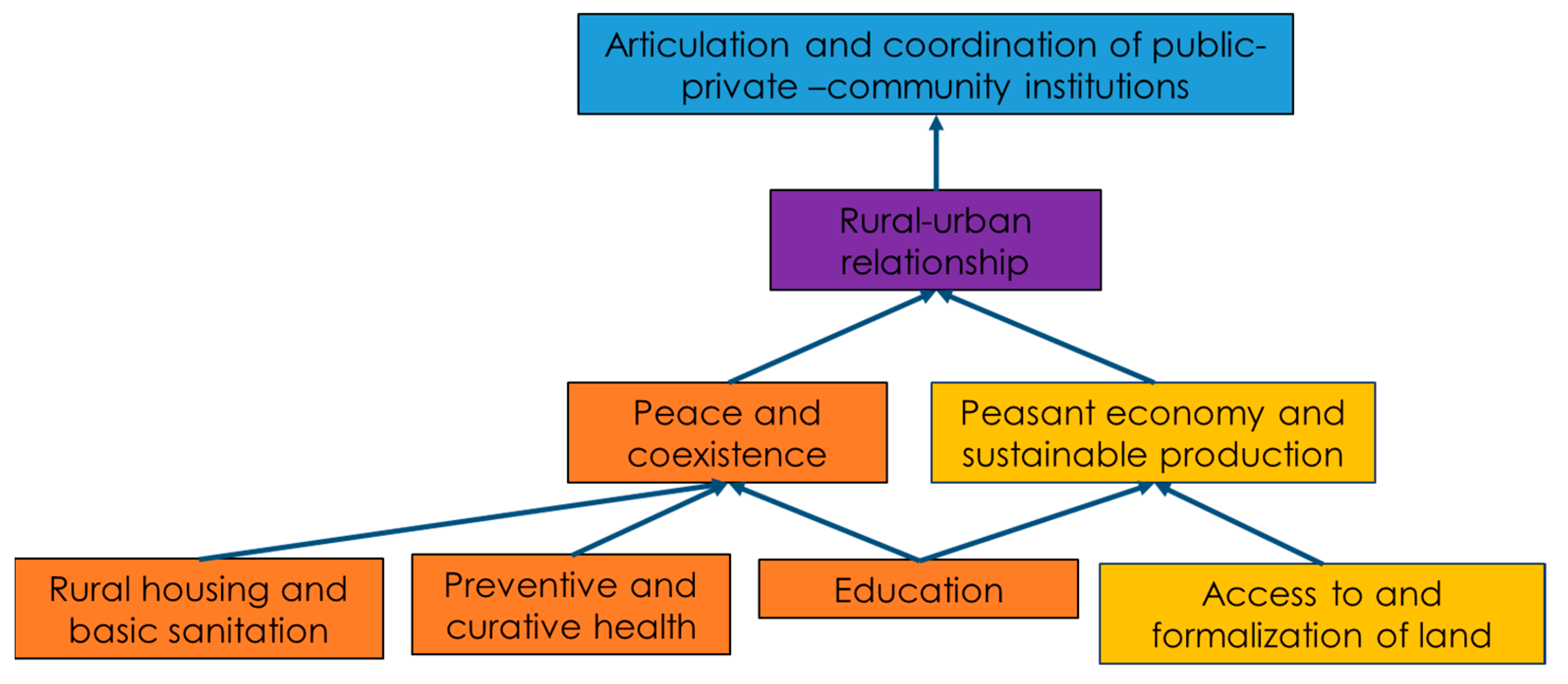

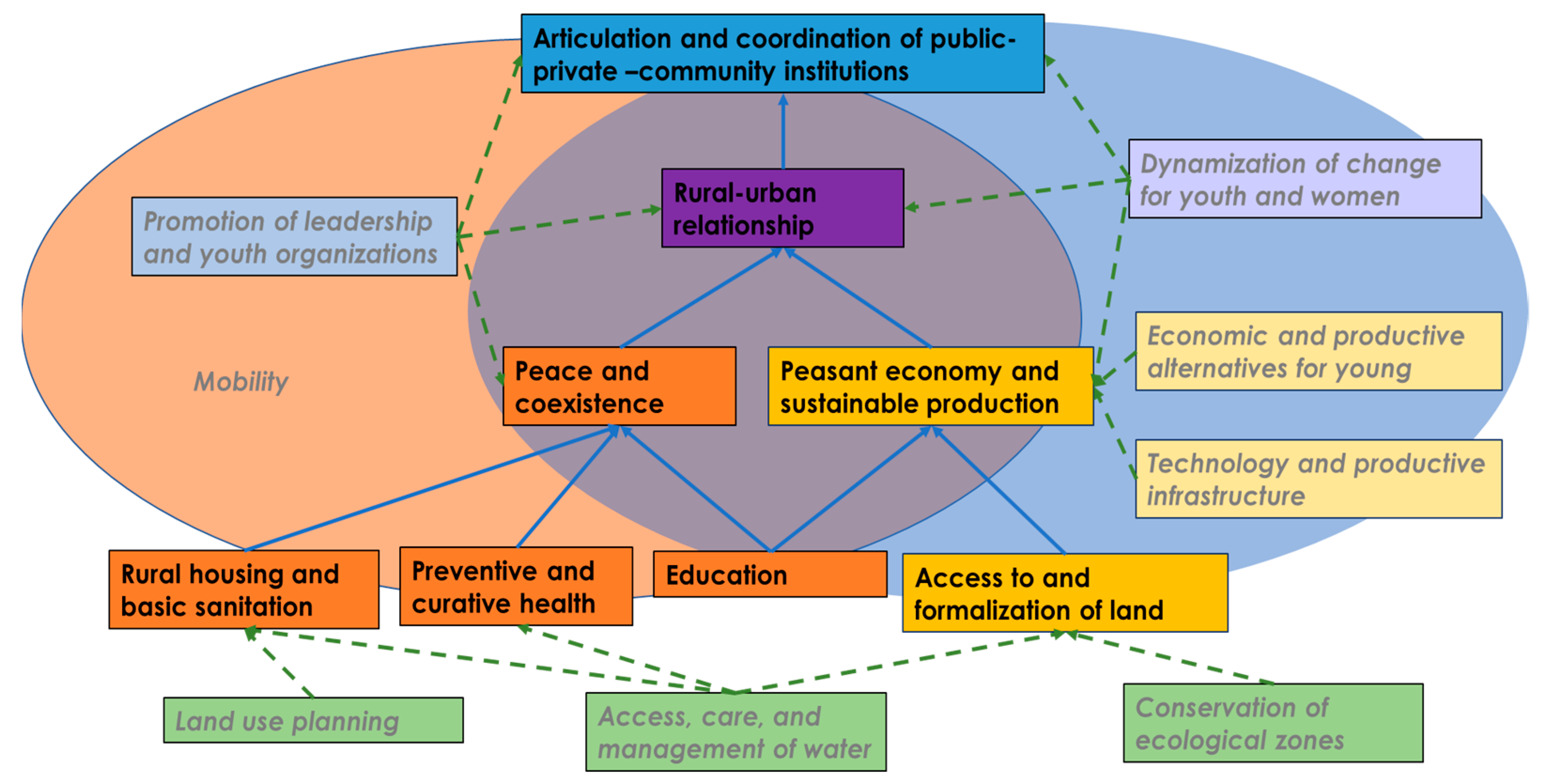

Given those policies, it is seen that not all are at the same level, and not all have the same impact or the same priority. Essential policies are those that are required to start a development process, without which this development is not possible. Enabling policies are those that support essential policies and act as "levers" of development, increasing hte speed in which some actions will be implemented. Finally, complementary policies are those which are not essential but once the essential actions are carried out, can give higher values to the development actions. A first analys of the relationships between those policies is seen in Peña Orozco et al. (2024), showing that complementary policy actions are not important, but shows that some policies are needed before others to ensure a continuous and robust rural development. Moreover, the assessment proposed by the authors (based on a Colombian case, then validated with a set of experts from Colombia and the Mediterranean area) confirms that some actions lead to others, so policy strategic guidelines would be hierarchized. Figure 1 shows the hierarchy of essential policy strategic lines, as agreed by the eight experts of the two regions:

4. Implementing public policy actions in rural development

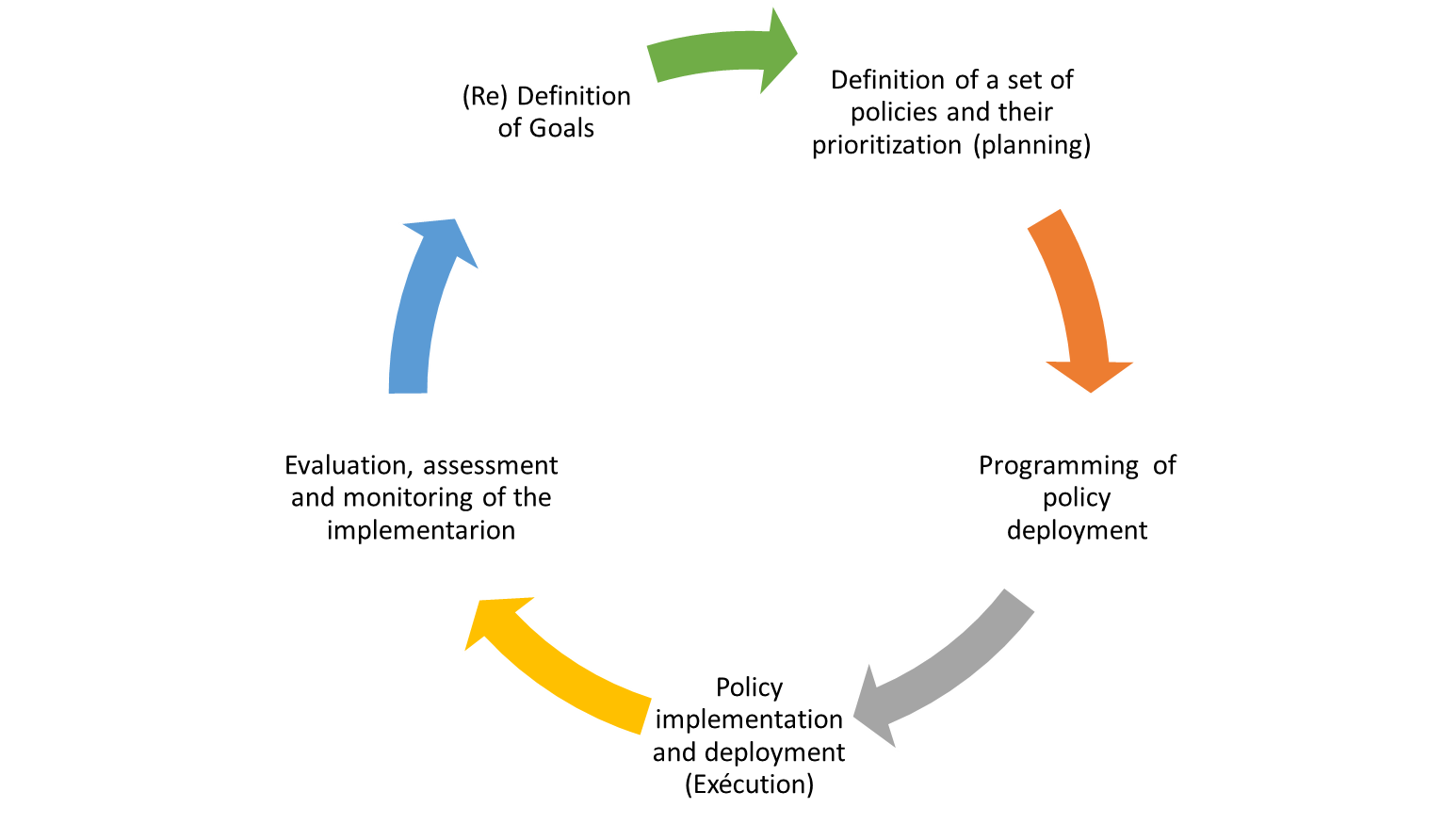

The proposed typology and hierarchization of public policy strategic lines and actions has a direct impact on its deployment and implementation. Indeed, if those policies are related and there are some hierarchies, their implementation needs to consider them, and their deployment cannot be linear but is more related to that of a project where the beginning of each task depends on its precedence constaint verification (Schwindt and Zimmerman 2015). This leads researchers to the notion of planning, since implementing a set of policies depends on how this implementation has been prepared and planned in advance. Plannign can be defined as a process to assess the futurability of present decisions (Drucker 1959), or, in other words, the design of a suitable future (Ackoff 1970). It is needed to anticipate decision making to anticipate a future state that depends on a set of interdependent decisions (known as decision system), and when that future cannot arrive alone, without the deployment of various actions. Bringing planning to public policy in rural development, the process can be decomposed in the following stages, as an extension of the PrOACT way of thinking (Keeney 1999, Raiffa 2007) but also in the planning vision of Ackoff (1970) and :

- First, the main Problems are defined, mainly via a characterization or a general diagnosis. In the case of rural development, this meansto identify the main weaknesses and lacks of the current state of a given rural territory.

- Second, Objectives (or goals) are set, if possible collectively. This is crucial to then propose the most suitable set of policies.

- Third, the different possible policies are examined and grouped into possible sets of actions or Alternatives, and their impacts in the development of the given rural territory assessed (i.e. their Consequences are evaluated).

- Fourth, Tradeoffs and agreements are made among stakeholders to select the most suitable set of policis to implement.

- Fifth, a deployment plan is defined and responsibilities and milestones set.

- Sixth and finally, the policy deployent is followed-up and its efficiency and degree of deployment evaluated using suitable tools and methods

In implementing policy actions for territorial development, researchers can define three crucial phases which impact the effective deployment of project, action or plan (Ackoff 1970): (1) the diagnosis phase, which will lead to the understanding of the decision problem and then to the proposal of the right way of action to deal with this problem (Gonzalez-Feliu and Gatica 2022); (2) the programming phase in which the deployment of chosen solution (i.e. the set of public policies to implement) is organized; and (3) the evaluation of the good implementation, which takes part in the execution or deployment phase.

Figure 3. The policy planning and implementation cycle (own elaboration from considerations given above).

Implementing rural development policies, as a territorial action, needs to take into account the components of territorial development (Gonzalez-Feliu and Cedillo Campos 2017, Torricelli 2018), and in a logic of sustainable development (Masson and Petiot 2012, Vargas et al. 2021), the three spheres of sustainable development, as well as the involved stakehoders with their purposes and their interactions (see Figure 4):

Figure 4. Interaction issues between logistics and territorial planning.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/economies12010003

References

- Maiorano, Diego, Suruchi Thapar-Björkert, and Hans Blomkvist. 2022. Politics as negotiation: Changing caste norms in rural India. Development and Change 53: 217–48.

- Zamarreño-Aramendia, Gorka, Elena Cruz-Ruiz, and Elena Ruiz-Romero de la Cruz. 2021. Sustainable economy and development of the rural territory: Proposal of wine tourism itineraries in La Axarquía of Malaga (Spain). Economies 9: 29.

- Pangratie, Alexandru, Ioan Csosz, Teodor Mateoc, Hunor Vass, and Nicoleta Mateoc-Sîrb. 2020. Agriculture and rural development-categories of investments and instruments to support them. Agricultural Management/Lucrari Stiintifice Seria I, Management Agricol 22: 94–103.

- Murdoch, Jonathan. 2000. Networks—A new paradigm of rural development? Journal of Rural Studies 16: 407–19.

- Naldi, Lucia, Pia Nilsson, Hans Westlund, and Sofia Wixe. 2015. What is smart rural development? Journal of Rural Studies 40: 90–101.

- Salemink, Koen, Dirk Strijker, and Gary Bosworth. 2017. Rural development in the digital age: A systematic literature review on unequal ICT availability, adoption, and use in rural areas. Journal of Rural Studies 54: 360–71.

- Barrios, Erniel B. 2008. Infrastructure and rural development: Household perceptions on rural development. Progress in Planning 70: 1–44.

- Liu, Jing, Xiaobin Jin, Weiyi Xu, and Yinkang Zhou. 2022. Evolution of cultivated land fragmentation and its driving mechanism in rural development: A case study of Jiangsu Province. Journal of Rural Studies 91: 58–72.

- Torre, André, Frédéric Wallet, and Jiao Huang. 2023. A collaborative and multidisciplinary approach to knowledge-based rural development: 25 years of the PSDR program in France. Journal of Rural Studies 97: 428–37.

- De Janvry, Alain, Elisabeth Sadoulet, and Rinku Murgai. 2002. Rural development and rural policy. In Handbook of Agricultural Economics. Edited by Bruce L. Gardner and Gordon C. Rausser. Amsterdam: Elsevier, vol. 2, part B. pp. 1593–658.

- Padmanabhan, Kuppuswamy P. 1988. Rural Credit: Lessons for Rural Bankers and Policy Makers. Warwickshire: Intermediate Technology Publications.

- Brauer, René, and Mirek Dymitrow. 2014. Quality of life in rural areas: A topic for the Rural Development policy? Bulletin of Geography. Socio-Economic Series 25: 25–54.

- Maîtrot, Mathilde. 2022. The Moral Economy of Microfinance in Rural Bangladesh: Dharma, Gender and Social Change. Development and Change 53: 335–55.

- Drescher, Axel W. 2002. Food for the cities: Urban agriculture in developing countries. ISHS Acta Horticulturae 643: 227–31.

- Belshaw, Deryk G. 1977. Rural development planning: Concepts and techniques. Journal of Agricultural Economics 28: 279–92.

- Popper, Frank J. 1993. Rethinking regional planning. Society 30: 46–54.

- Ackoff, Russell L. 1977. National development planning revisited. Operations Research 25: 207–18.

- Ackoff, Russell L. 1997. Systems, messes and interactive planning. In The Societal Engagement of Social Science. Edited by Eric Trist, Fed Emery and Hugh Murray. Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press, vol. 3, pp. 417–38.

- Jackson, Michael C. 1982. The nature of soft systems thinking: The work of Churchman, Ackoff and Checkland. Journal of Applied Systems Analysis 9: 17–29.

- Jiménez, Jaime. 1992. Surutato: An experience in rural participative planning. In Planning for Human Systems: Essays in Honor of Russell L. Ackoff. Edited by Jean-Marc Choucroun and Roberta M. Snow. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 407–16.

- Rojas Palacios, Margy Nathalia, Diego León Peña Orozco, and Jesús Gonzalez-Feliu. 2022. Backup Agreement as a Coordination Mechanism in a Decentralized Fruit Chain in a Developing Country. Games 13: 36.

- Ashley, Caroline, and Simon Maxwell. 2001. Rethinking rural development. Development Policy Review 19: 395–425.

- Abreu, Isabel, and Francisco J. Mesias. 2020. The assessment of rural development: Identification of an applicable set of indicators through a Delphi approach. Journal of Rural Studies 80: 578–85.

- Auliah, Aidha, Gunawan Prayitno, Ismu Rini Dwi Ari, Rahmawati, Lusyana Eka Wardani, and Christia Meidiana. 2022. The Role of Social Capital Facing Pandemic COVID-19 in Tourism Village to Support Sustainable Agriculture (Empirical Evidence from Two Tourism Villages in Indonesia). Economies 10: 320.

- Castro-Arce, Karina, and Frank Vanclay. 2020. Transformative social innovation for sustainable rural development: An analytical framework to assist community-based initiatives. Journal of Rural Studies 74: 45–54.

- Ogujiuba, Kanayo, and Ntombifuthi Mngometulu. 2022. Does social investment influence poverty and economic growth in South Africa: A cointegration analysis? Economies 10: 226.

- Ali, Ifzal, and Hyun Hwa Son. 2007. Measuring inclusive growth. Asian Development Review 24: 11–31.

- Heshmati, Almas, Jungsuk Kim, and Jacob Wood. 2019. A survey of inclusive growth policy. Economies 7: 65.

- Thomas, Howard, and Yuwa Hedrick-Wong. 2019. Inclusive Growth. London: Emerald.

- Reddy, A. 2010. Rural banking strategies for inclusive growth. The India Economy Review 7: 8–13.

- Kvist, Elin. 2020. Who’s there?–Inclusive growth,‘white rurality’and reconstructing rural labour markets. Journal of Rural Studies 73: 234–42.

- Ghanem, Hafez. 2014. Improving Regional and Rural Development for Inclusive Growth in Egypt. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, Brookings Global Working Paper Series n. 2014-67.

- Weiss, Janet A. 2000. From research to social improvement: Understanding theories of intervention. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 29: 81–110.

- Gharajedaghi, Jamshid, and Russell L. Ackoff. 1984. Mechanisms, organisms and social systems. Strategic Management Journal 5: 289–300.

- Ackoff, Russell L., and Fred E. Emery. 2005. On Purposeful Systems: An Interdisciplinary Analysis of Individual and Social Behavior as a System of Purposeful Events. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

- Ulrich, Hans, and Gilbert J. B. Probst, eds. 2012. Self-Organization and Management of Social Systems: Insights, Promises, Doubts, and Questions. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer Science & Business Media, vol. 26.

- Sweet, Timothy. 2011. What Is Improvement? The Eighteenth Century 52: 225–30.

- Beyer, Robert. 1969. The modern management approach to a program of social improvement. Journal of Accountancy 127: 37–46.

- Massie, James William. 1849. Social Improvement Among the Working Classes Affecting the Entire Body Politic. Second Lecture of the Course by Request of the Congregational Union of England and Wales. London: Partridge and Oakey.

- Collins, Michael, and Joanna Swann. 2003. Research and social improvement: Critical theory and the politics of change. In Educational Research in Practice: Making Sense of Methodology. Edited by John Pratt and Joanna Swann. London: Blomsbury Publishing, pp. 141–51.

- Reimers, Fernando M. 2013. Education for improvement. Harvard International Review 35: 56–61.

- Maldonado, Mariela, and Silvia Moya. 2013. The Challenge of Implementing Reverse Logistics in Social Improvement: The Possibility of Expanding Sovereignty Food in Developing Communities. In Logistics: Perspectives, Approaches and Challenges. New York: Nova Science, pp. 1–34.

- Lawson, Hal A. 1993. School reform, families, and health in the emergent national agenda for economic and social improvement: Implications. Quest 45: 289–307.

- McCann, Eugene J. 2002. The cultural politics of local economic development: Meaning-making, place-making, and the urban policy process. Geoforum 33: 385–98.

- Terluin, Ida Joke, and Pim Roza. 2010. Evaluation Methods for Rural Development Policy. Hague: LEI Wageningen UR.

- Hălbac-Cotoară-Zamfir, Rareș, Saskia Keesstra, and Zahra Kalantari. 2019. The impact of political, socio-economic and cultural factors on implementing environment friendly techniques for sustainable land management and climate change mitigation in Romania. Science of the Total Environment 654: 418–29.

- Tabares, Alexander, Abraham Londoño-Pineda, Jose Alejandro Cano, and Rodrigo Gómez-Montoya. 2022. Rural entrepreneurship: An analysis of current and emerging issues from the sustainable livelihood framework. Economies 10: 142.

- Briones, Roehlano M. 2013. Agriculture, Rural Employment, and Inclusive Growth. PIDS Discussion Paper Series n. 2013-39. Makati City: Philippine Institute for Development Studies (PIDS).

- World Health Organization. 1961. Rural Health. No. EM/RC11/8. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- Gonzalez-Feliu, Jesus, Carlos Osorio-Ramírez, Laura Palacios-Arguello, and Carlos Alberto Talamantes. 2018. Local production-based dietary supplement distribution in emerging countries: Bienestarina Distribution in Colombia. In Establishing Food Security and Alternatives to International Trade in Emerging Economies. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 297–315.

- Maldonado-Mariscal, Karina, and Iwan Alijew. 2023. Social innovation and educational innovation: A qualitative review of innovation’s evolution. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 36: 1–26.

- Umpleby, Stuart, and Svitlana Shandruk. 2013. Transforming the global university system into a resource for social improvement. In Global Integration of Graduate Programs Donetsk Scientific Centre. Kiev: National Academy of Science in Ukraine, pp. 192–97.

- Collett, Kathleen, and Chris Gale. 2009. Training for Rural Development: Agricultural and Enterprise Skills for Women Smallholders. London: City and Guilds Centre for Skills Development.

- Shucksmith, Mark, and Pollyanna Chapman. 1998. Rural development and social exclusion. Sociologia Ruralis 38: 225–42.

- Hart, Tim, Peter Jacobs, Kgabo Ramoroka, Hlokoma Mangqalaza, Alexandra Mhula, Makale Ngwenya, and Brigid Letty. 2014. Social Innovation in South Africa’s Rural Municipalities: Policy Implications. Pretoria: Department of Science and Technology, Human Sciences Research Council n. 2012-3.

- Giessen, Lukas. 2010. Potentials for Forestry and Political Drivers in Integrated Rural Development Policy. Göttingen: Universitätsverlag Göttingen.

- Reina-Usuga, Martha Liliana, Wilson Adarme-Jaimes, and Oscar Eduardo Suarez. 2012. Coordination on agrifood supply chain. In Proceedings of World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology. Istanbul: World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology (WASET), vol. 71, pp. 337–61.

- Meyer, Hester W. J. 2003. Information use in rural development. The New Review of Information Behaviour Research 4: 109–25.

- Oakley, Peter, and David Marsden. 1984. Approaches to Participation in Rural Development. Geneva: International Labour Office.

- Boliko, Mbuli Charles. 2019. FAO and the situation of food security and nutrition in the world. Journal of Nutritional Science and Vitaminology 65: S4–S8.

- Ratner, Shanna E. 2019. Wealth Creation: A New Framework for Rural Economic and Community Development. London: Routledge.

- Bebbington, Anthony. 1999. Capitals and capabilities: A framework for analyzing peasant viability, rural livelihoods and poverty. World Development 27: 2021–44.

- Robison, Lindon J., and A. Allan Schmid. 1994. Can agriculture prosper without increased social capital? Choices 9: 29–31.

- Saikouk, Tarik, and Ismail Badraoui. 2014. Managing Common Goods in Supply Chain: Case of Agricultural Cooperatives. In Innovative Methods in Logistics and Supply Chain Management: Current Issues and Emerging Practices. In Proceedings of the Hamburg International Conference of Logistics (HICL). Berlin: Epubli GmbH, vol. 18, pp. 477–98.

- Häuberer, Julia. 2011. Social Capital Theory. Berlin: Springer Fachmedien, vol. 4.

- Dubos, Rene. 2017. Social Capital: Theory and Research. London: Routledge.

- Irwin, Linda, Isabel Rimanoczy, Morgane Fritz, and James Weichert, eds. 2023. Transforming Business Education for a Sustainable Future: Stories from Pioneers. London: Routledge.