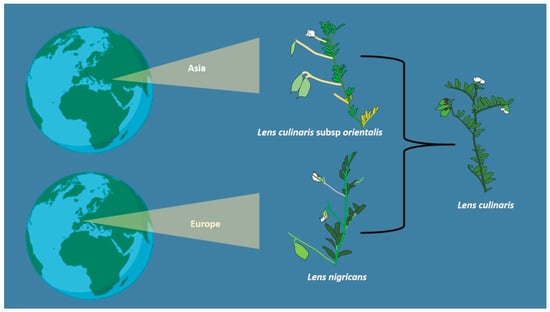

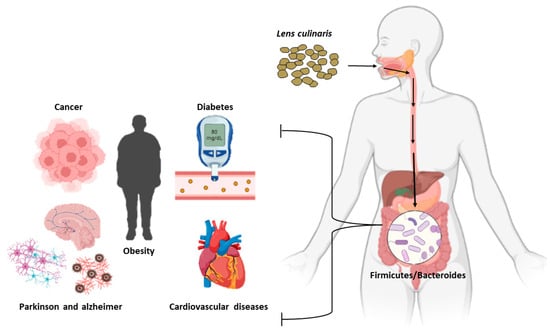

The legume family includes approximately 19,300 species across three large subfamilies, of which Papilionoideae stands out with 13,800 species. Lentils were one of the first crops to be domesticated by humans. They are diploid legumes that belong to the Papilionoidea subfamily and are of agricultural importance because of their resistance to drought and the fact that they grow in soil with a pH range of 5.5–9; therefore, they are cultivated in various types of soil, and so they have an important role in sustainable food and feed systems in many countries. In addition to their agricultural importance, lentils are a rich source of protein, carbohydrates, fiber, vitamins, and minerals. They are key to human nutrition since they are an alternative to animal proteins, decreasing meat consumption.

- lentils

- nutrition

- legume

- protein

- prebiotic

- carbohydrates

1. Introduction

2. Effect of Lentil Consumption on Human Health

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/agriculture14010103

References

- LPWG. Legume phylogeny and classification in the 21st century: Progress, prospects and lessons for other species-rich clades. Taxon 2013, 62, 217–248.

- LPWG. A new subfamily classification of the Leguminosae based on a taxonomically comprehensive phylogeny. Taxon 2017, 66, 44–77.

- Schaefer, H.; Hechenleitner, P.; Santos-Guerra, A.; Menezes de Sequeira, M.; Pennington, R.T.; Kenicer, G.; Carine, M.A. Systematics, biogeography, and character evolution of the legume tribe Fabeae with special focus on the middle-Atlantic island lineages. BMC Evol. Biol. 2012, 12, 250.

- Cárdenas, T.R.M.; Ortiz, P.R.H.; Rodríguez, M.O.; de la Fe, M.C.F.; Lamz, P.A. Comportamiento agronómico de la lenteja (Lens culinaris Medik.) en la localidad de Tapaste, Cuba. Cultiv. Trop. 2014, 35, 92–99.

- Zafar, M.; Maqsood, M.; Anser, M.R.; Ali, Z. Growth and yield of lentil as affected by phosphorus. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2003, 5, 98–100.

- Nutritionvalue.org. Nutrition Value: Find Nutritional Value of a Product. Available online: https://www.nutritionvalue.org/ (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- FAOSTAT. Statistics division, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QI (accessed on 15 December 2023).

- Zhang, B.; Peng, H.; Deng, Z.; Tsao, R. Phytochemicals of lentil (Lens culinaris) and their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects. J. Food Bioact. 2018, 1, 93–103.

- Andrews, M.; Raven, J.A.; Lea, P.J. Do plants need nitrate? The mechanisms which nitrogen form affects plants. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2013, 163, 174–199.

- Ladizinsky, G. The origin of lentil and its wild genepool. Euphytica 1979, 28, 179–187.

- Sonnante, G.; Hammer, K.; Pignone, D. From the cradle of agriculture a handful of lentils: History of domestication. Rend. Lincei. Sci. Fis. Nat. 2009, 20, 21–37.

- Renfrew, J.M. The archeological evidence for the domesticastion of plants: Methods and problems. In The Domestication and Exploitation of Plants and Animals; Ucko, P.J., Dimbleby, G.W., Eds.; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1969.

- Havey, M.J.; Muehlbauer, F.J. Variability for restriction fragment lengths and phylogenies in lentil. TAG Theor. Appl. Genetics. Theor. Und Angew. Genet. 1989, 77, 839–843.

- Ladizinsky, G.; Braun, D.; Goshen, D.; Muehlbauer, F.J. Evidence for domestication of Lens nigricans (M. Bieb.) Godron in S. Europe. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 1983, 87, 169–176.

- Zohary, D.; Hopf, M.; Weiss, E. Domestication of Plants in the Old World: The Origin and Spread of Domesticated Plants in Southwest Asia, Europe, and the Mediterranean Basin; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2012.

- Maxted, N.; Kell, S.; Toledo, A.; Dulloo, M.; Heywood, V.; Hodgkin, T.; Hunter, D.; Guarino, L.; Jarvis, A.; Ford-Lloyd, B. A global approach to crop wild relative conservation: Securing the gene pool for food and agriculture. Kew Bull. 2010, 65, 561–576.

- Ferguson, M.; Acikgoz, N.; Ismail, A.; Cinsoy, A. An ecogeographic survey of wild Lens species in Aegean and south west Turkey. Anadolu 1996, 6, 159–166.

- van Oss, H.; Aron, Y.; Ladizinsky, G. Chloroplast DNA variation and evolution in the genus Lens Mill. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1997, 94, 452–457.

- Zohary, D. The wild progenitor and the place of origin of the cultivated lentil: Lens culinaris. Econ. Bot. 1972, 26, 326–332.

- Gibson, G.R.; Hutkins, R.; Sanders, M.E.; Prescott, S.L.; Reimer, R.A.; Salminen, S.J.; Scott, K.; Stanton, C.; Swanson, K.S.; Cani, P.D.; et al. Expert consensus document: The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on the definition and scope of prebiotics. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 14, 491–502.

- Thaiss, C.A.; Itav, S.; Rothschild, D.; Meijer, M.T.; Levy, M.; Moresi, C.; Dohnalová, L.; Braverman, S.; Rozin, S.; Malitsky, S.; et al. Persistent microbiome alterations modulate the rate of post-dieting weight regain. Nature 2016, 540, 544–551.

- Collins, S.M.; Surette, M.; Bercik, P. The interplay between the intestinal microbiota and the brain. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2012, 10, 735–742.

- Sanchez-Rodriguez, E.; Egea-Zorrilla, A.; Plaza-Díaz, J.; Aragón-Vela, J.; Muñoz-Quezada, S.; Tercedor-Sánchez, L.; Abadia-Molina, F. The Gut Microbiota and Its Implication in the Development of Atherosclerosis and Related Cardiovascular Diseases. Nutrients 2020, 12, 605.

- Chen, Y.; Zhou, J.; Wang, L. Role and Mechanism of Gut Microbiota in Human Disease. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 625913.

- Siva, N.; Johnson, C.R.; Richard, V.; Jesch, E.D.; Whiteside, W.; Abood, A.A.; Thavarajah, P.; Duckett, S.; Thavarajah, D. Lentil (Lens culinaris Medikus) Diet Affects the Gut Microbiome and Obesity Markers in Rat. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018, 66, 8805–8813.

- Verni, M.; Demarinis, C.; Rizzello, C.G.; Baruzzi, F. Design and characterization of a novel fermented beverage from lentil grains. Foods Foods 2020, 9, 893.

- Adsule, R.N.; Kadam, S.S.; Leung, H.K. Lentil. In Handbook of World Food Legumes: Nutritional Chemistry, Processing Technology, and Utilization; Salunkhe, D.K., Kadam, S.S., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1989; Volume II, pp. 133–152.

- Lombardi-Boccia, G.; Ruggeri, S.; Aguzzi, A.; Cappelloni, M. Globulins enhance in vitro iron but not zinc dialysability: A study on six legume species. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2013, 17, 1–5.

- Asif, M.; Rooney, L.W.; Ali, R.; Riaz, M.N. Application and opportunities of pulses in food system: A review. Crit. Rev. Food. Sci. Nutr. 2013, 53, 1168–1179.

- Bhatty, R.S. Protein subunits and amino acid composition of wild lentil. Phytochem 1986, 25, 641–644.

- Tripathi, K.; Gore, P.G.; Pandey, A.; Bhardwaj, R.; Singh, N.; Chawla, G.; Kumar, A. Seed morphology, quality traits and imbibition behavior study of atypical lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.) from Rajasthan, India. Genet. Resour. Crop. Evol. 2019, 66, 697–706.

- Ali, J.A.F.; Shaikh, N.A. Genetic exploitation of lentil through induced mutations. Pak. J. Bot. 2007, 39, 2379–2388.