You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Dermatology

Inflammatory skin diseases, also called inflammatory dermatoses, are a group of immune-mediated skin diseases with a complex etiology in which both genetic and environmental (i.e., lifestyle) factors play an essential role. Psoriasis and hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) are two of the many diseases that are encompassed by this term. It has been shown that pyroptosis plays a role in the development and exacerbation of comorbidities occurring in patients suffering from psoriasis and HS.

- hidradenitis suppurativa

- psoriasis

- inflammatory dermatoses

- pyroptosis

- inflammasome

- NLRP3

- inflammation

1. Introduction

Inflammatory skin diseases, also called inflammatory dermatoses, are a group of immune-mediated skin diseases with a complex etiology in which both genetic and environmental (i.e., lifestyle) factors play an essential role [1]. Psoriasis and hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) are two of the many diseases that are encompassed by this term [1]. These two disorders, although clinically very diverse, share several pathogenetic pathways, including, in both cases, an unbalanced interaction between the adaptive and innate immune systems [2]. Psoriasis and HS also share potential environmental factors for the development and exacerbation of both diseases, which include smoking, alcohol intake, obesity, metabolic syndrome, and dysbiosis [3,4,5,6,7,8]. The molecular changes in the psoriatic skin lead to the activation and proliferation of keratinocytes, causing epidermal hyper- and parakeratosis, as well as neutrophilic infiltration of the epidermis [9]. Moreover, the critical element of HS pathogenesis includes the occlusion of the infundibulum of the pilosebaceous unit, its dilation, and rupture, followed by a creation of inflammatory nodules and tunnels with progressive scarring [7]. Interestingly, similarly to psoriasis, the occlusion of the pilosebaceous unit in HS is initiated by the hyperkeratosis and hyperplasia of the keratinocytes localized mainly in the infundibular epithelium [7,9]. The multitude of ongoing studies on the pathomechanisms of psoriasis and HS have led to its meticulous description. It is known that in both disorders, the activation of the dendritic cells, secretion of IL-23, and subsequent differentiation of T helper lymphocytes (Th) lead to the increased proliferation of Th17, Th1, and Th22 [7,10,11]. These T-cells cause the excessive production of interleukin (IL)-17, IL-22, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) [7,10,11], which, as a result, drives the vicious inflammatory cycle leading to the further development of CD4+ T-cells and production of inflammatory cytokines [7,10,11]. Moreover, in the pathogenesis of HS, additional pathogenetic pathways have been described [7]. Complement activation by pathogen- and damage-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs and DAMPS) leads to inflammasome activation, the production of caspase-1, and release of IL-1β and TNF-α [12]. Although many pathogenetic pathways of both diseases have already been described, the exact pathomechanism is still yet to be fully elucidated. Pathogenetic advancements have led to the development of many pathway-specific medications, including biologics and Janus kinase inhibitors (JAKi) [6,12].

The similar pathomechanisms of the two disorders allow for the interchangeable use of psoriatic drugs in HS patients [2]. Nonetheless, even the newest biological drugs, allowing us to almost entirely eradicate skin lesions in psoriatic patients, frequently present incomparably worse responses in patients with HS [13,14]. Therefore, future research targeting possible inflammatory pathways in both diseases is necessary for the development of new, effective therapies.

2. Pyroptosis—Inflammatory, Programmed Cell Death

The removal of damaged and senescent cells is crucial for maintaining the homeostasis of every healthy multicellular organism. There are two basic pathways of programmed cell death, lytic and non-lytic [15]. Initially, only apoptosis was known to be programmed and strictly regulated, while necrosis was considered a form of unregulated cell death [15]. Recently, scientists have discovered differently regulated pathways of necrosis that may be activated by regulated stimuli [16]. Necroptosis and pyroptosis, classified as lytic forms of programmed cell death, were also considered inflammatory due to the release of proinflammatory molecules (DAMPs and cytokines) [16,17]. Both necroptosis and pyroptosis are examples of regulated necrosis; nonetheless, they are triggered by different stimuli and follow different pathways [15]. Pyroptosis, as a form of cell death, was first described in murine macrophage models by Zychlinsky et al. [18] in 1992. At first, it was incorrectly classified as apoptosis and later identified as a form of non-apoptotic cell death [15]. The word pyroptosis comes from Greek and translates into pyro (fire), ptosis (falling) [19]. The pyroptosis begins with the activation of inflammasomes, complex assemblies of multiple proteins activating caspase-1. Various distinct inflammasomes have been identified, each characterized by their unique activators, receptor classes, and the type of activated caspase [20]. The NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome should be underlined due to recent studies on its function in the development of inflammatory dermatoses [21,22,23].

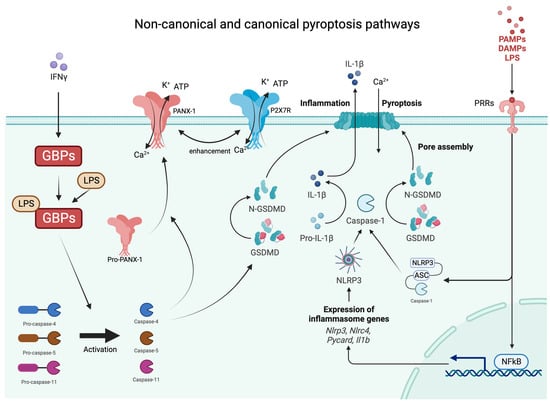

Inflammasomes are innate immune system protein complexes that act as receptors or sensors to PAMPs and DAMP by promoting the maturation of proinflammatory IL-1β and IL-18 [24]. Inflammasomes form when cellular sensors detect PAMPs or DAMPs. The cellular sensors include, among others, absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2), caspase recruitment domain-containing protein 8 (CARD8), NOD-like receptors (NLRs), and pyrin. These sensors then trigger the activation of the effector enzyme through an adaptor molecule known as ASC (apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a CARD) [25]. During pyroptosis, caspase-1 cleaves gasdermin D (GSDMD), releasing its N-terminal domain from the C-terminal domain [26]. Additionally, caspase-11 and its human counterparts, caspase-4 and -5, can trigger pyroptosis by cleaving GSDMD at the same site as caspase-1 [26,27,28]. Once GSDMD is cleaved, the liberated N-terminal fragments undergo structural changes, leading to their oligomerization in the cellular membrane and the formation of large transmembrane β-barrel pores [29]. These β-barrel pores serve as channels connecting the cytosol to the extracellular space, allowing the release of DAMPs, including mature IL-1β, which attracts immune cells and triggers inflammation [28,30,31]. As previously mentioned, IL-1β has a crucial role in the differentiation and activation of Th17 cells producing IL-17 [32]. Moreover, IL-1β has been reported to be significantly increased in patients with psoriasis and even more in HS, both on the transcriptional and protein levels [33,34]. Furthermore, HS lesional and non-lesional adjacent skin shows a higher expression of IL-1β in comparison to healthy controls (HC) (data yet not published). While various mechanisms for the secretion of IL-1β from viable cells have been described in recent studies [35], pyroptosis and necroptosis are increasingly recognized as the primary pathways responsible for the release of IL-1β and IL-18, DAMPs, ATP, HMGB1, S100 proteins, and IL-1α [36]. Pyroptosis and apoptosis can be differentiated in several ways [15]. Morphologically, pyroptosis is characterized by a rapid loss of plasma membrane integrity through pore formation, as opposed to the membrane blebbing seen in apoptosis. The subcellular events leading to plasma membrane breakdown in pyroptosis occur within minutes, which is in stark contrast to the relatively slow process of apoptosis. The degradation of membrane structure in pyroptosis leads to the influx of water and ions, resulting in cell swelling and eventual rupture [37]. The non-canonical and canonical pathways are demonstrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Graphical presentations of non-canonical and canonical pathways of pyroptosis. IFNy—interferon gamma; GBPs—guanylate binding proteins; Ca—calcium; K—potassium; ATP—adenosine triphosphate; PAMPs—pathogen-associated molecular patterns; DAMPs—damage-associated molecular patterns; LPS—lipopolysaccharides; PRRs—pattern recognition receptors; NLRP3—NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 inflammasome; GSDMD—gasdermin D.

3. The Role of Pyroptosis in Inflammatory Disorders Associated with Psoriasis/HS

3.1. Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD)

The coexistence of IBDs and chronic inflammatory skin disorder has been frequently reported [74]. In a cohort study performed by Schneeweis et al. [74], the authors found that patients with HS are at a higher risk of developing ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) (Hazard Ratio [HR] of 2.3 and 2.7, respectively). In contrast, psoriatic patients suffer 1.2 times more frequently from CD, but not UC, than HC [74]. Shared inflammatory pathways, including TNF, IL-17, and IL-23, are key inflammatory elements in the development of IBD [75]. Moreover, clinical trials have shown that similar therapeutic factors may alleviate symptoms of all the above-mentioned diseases [76,77,78]. Pyroptosis may also play a role in developing UC and CD gastrointestinal lesions. It controls bacterial and viral infections of the intestinal epithelium and stimulates host defenses from intracellular pathogens by enclosing them in pore-induced intracellular traps (PITs) in macrophages [79]. PITs additionally promote the innate immune response, which, as a result, recruits more inflammatory cells, including neutrophils and macrophages [79]. The role of GSDMs in the development of IBDs is complex and still remains unclear. Patients who suffer from IBD present higher expressions of GSDMD and GSDME in the intestinal epithelium [80,81,82]. Furthermore, mRNA expressions of Nima associated kinase 7 (NEK7), a protein interacting with NRLP3, Caspase-1, and GSDMD, were significantly higher in UC patients in comparison to HC [83,84]. Likewise, NEK7 deficiency was associated with a lower expression of NRLP3 itself, Caspase-1, and GSDMD [83]. Moreover, GSDMD deficiency aggravates experimental colitis through cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)-dependent inflammation [85]. On the other hand, the inflammation caused by GSDME was associated with the development of colorectal cancer associated with chronic colitis [80].

3.2. Diabetes Mellitus (DM)

Obesity, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes are some of the most commonly mentioned comorbidities of psoriasis and HS. The pathogenesis of those comorbidities remains unclear. However, mutual inflammatory pathways, shared cellular mediators, genetic susceptibility, and risk factors of these diseases have been described [86,87]. The role of pyroptosis in the pathophysiology of diabetes and diabetic neuropathy has been vastly studied. Increased expressions of NLRP3 and IL-1β were observed in the non-obese diabetic mice (type 1 DM) [88]. Conversely, saturated fatty acids, which promote the development of type 2 DM activated NLRP3, promote the production of IL-1β and the further activation of caspase-1 in macrophages [89]. On the contrary, unsaturated fatty acids inhibited the activation of NLRP3, resulting in decreased activation of caspase-1, thus preventing the development of obesity and DM2 [90]. It has been recently revealed that thioredoxin-interacting protein (TXNIP), a key element of diabetes progression, activates the NLRP3 inflammasome and subsequent pancreatic B-cell pyroptosis in diabetic mice [91]. It was also reported that the inhibition of TXNIP is effective in preventing diabetes complications [92]. In individuals with diabetes, there was a statistically significant increase in the levels of NLRP3, ASC, and subsequent proinflammatory factors [93]. Conversely, a reduction in calorie intake and weight loss through exercise among obese individuals with type 2 diabetes resulted in a significant decrease in mRNA levels of NLRP3 and IL-1β. This intervention also led to an improvement in insulin sensitivity [94]. In summary, pyroptosis plays a role in inflammation, the destruction of beta cells, insulin resistance, and the development of diabetes.

3.3. Cardiovascular Disorders

Patients suffering from psoriasis and HS are at a higher risk of developing life-threatening cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) due to a common prevalence of CV risk factors, as well as a common inflammatory pathway, which leads to the creation of atherosclerosis [87,95]. Research has indicated that pyroptosis plays a significant role in the development of various cardiovascular diseases. The occurrence of pyroptosis in endothelial cells, macrophages, and smooth muscle cells is closely linked to the initiation and progression of atherosclerotic lesions, impacting the stability of arterial plaques [96,97,98,99]. Additionally, the presence of NLRP3/IL-1β/caspase-1 has been detected in individuals with conditions such as diabetes, myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, and cardiac hypertrophy. Some treatments have shown promise in alleviating cardiovascular disease symptoms by reducing pyroptosis [100]. Among others, colchicine, a non-specific inhibitor of NLRP3, has been shown to significantly reduce infarct size in phase II clinical trials. Moreover, the inhibition of caspase-1, IL-1, and IL-18 may restore heart function [100]. In recent decades, an increasing body of evidence has pointed towards atherosclerosis as being an inflammatory disease linked to impaired endothelial function, with pyroptosis emerging as a critical contributor to this phenomenon [97,101,102]. Notably, components of the NLRP3 inflammasome, including NLRP3, ASC, and caspase-1, exhibit elevated expression within carotid atherosclerotic plaques, implying their involvement in atherosclerosis pathogenesis [103,104]. The adverse impact of NLRP3 on atherosclerosis primarily hinges on the action of its downstream cytokine IL-1β. Studies involving IL-1β-deficient mice reveal a nearly 30% reduction in atherosclerotic plaque size, possibly indicative of impaired monocyte migration to lipid deposition sites [105,106]. These findings affirm the role of pyroptosis in atherosclerotic plaque formation and suggest that targeting NLRP3 and IL-1β within the pyroptosis pathway could represent a potential strategy for atherosclerosis treatment [100].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cimb46010043

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!