Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Hematology

Anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have revolutionized the treatment of lymphomas by improving the survival of patients, particularly in conjunction with chemotherapy. Efforts to improve the on-targeting CD20 expressed on lymphomas through novel bioengineering techniques have led to the development of newer anti-CD20 mAbs that have accentuated complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC), antibody-dependent cell medicated cytotoxicity (ADCC), and/or a direct killing effect.

- CD20

- rituximab

- non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL)

- follicular lymphoma (FL)

- diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL)

1. Introduction

Anti-CD20 antibodies strategically bind to B-cells positive for CD20, a surface transmembrane protein marker [1]. Their ability to bind to CD20 markers and activate the direct signaling of apoptosis, facilitate complement activation and subsequent complement-mediated cytotoxicity (CDC), as well as induce antibody-induced cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC) through natural killer (NK) cells, plays an integral role in the treatment options for various lymphomas [1,2].

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) has several subtypes—follicular lymphoma (FL) and chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) are typically indolent, meanwhile diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is aggressive. The common feature amongst them is the malignant B-cell and its surface protein, CD20. Thus, antibodies that target CD20 have been pertinent in the evolution of NHL treatment [2,3].

Rituximab (RTX), a monoclonal antibody (mAb) against CD20, has been widely used for lymphoma therapy [3]. It has been in use for more than two and a half decades and has extensive clinical safety data. The most common adverse effect (AE) is an infusion-related reaction (IRR) and symptoms typically include fever and skin rash and may occasionally culminate in hypotension, shock or arrhythmias [4]. Another common AE is B-cell lymphopenia, which leads to an increased incidence of infections that are generally controlled by humoral immune responses [4].

RTX in combination with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (R-CHOP) remains the standard frontline regimen for DLBCL [3]. Obinutuzumab, another humanized mAb against CD20, has undergone glycoengineering and has distinctive mechanistic properties. Obinutuzumab in combination with bendamustine is approved for relapsed/refractory (R/R) FL patients treated with an RTX-containing regimen as well as the frontline treatment of FL [5]. Anti-CD20 antibodies are seldom used as monotherapy currently in CLL and are mostly used in conjunction with Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors (BTKi) or venetoclax.

2. Resistance to RTX and the Bioengineering of Newer Anti-CD20 Antibodies

Despite the widespread use of RTX, the mechanisms by which RTX resistance is conferred have not been clearly delineated. One theory is that continuous exposure exhausts the store of complement proteins, thus conferring resistance due to a depletion of the necessary effector molecules [18]. Klepfish et al. infused fresh frozen plasma (FFP) in conjunction with RTX into treatment-refractory CLL patients and found rapid and dramatic clinical responses in all patients [18]. A study from Xu et al. lends further support to this theory, as they reported similarly positive results when combining FFP with RTX [18]. Pederson et al. described a process of shaving, wherein RTX-CD20 complexes are shed off from cells by phagocytes, thus inducing refractoriness [19]. Wang et al. found that RTX-resistant cell lines demonstrated apoptosis resistance, in particular, due to the hyperactivated NF-kB pathway and Bcl2 overexpression [20]. Czuczman et al. supported this theory, reporting that constant RTX exposure resulted in a downregulation of the pro-apoptotic proteins Bax and Bak [21].

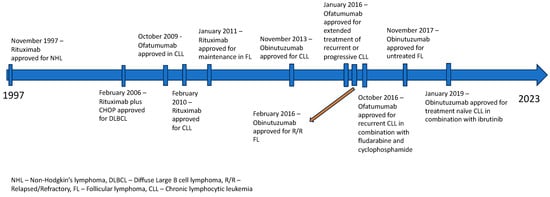

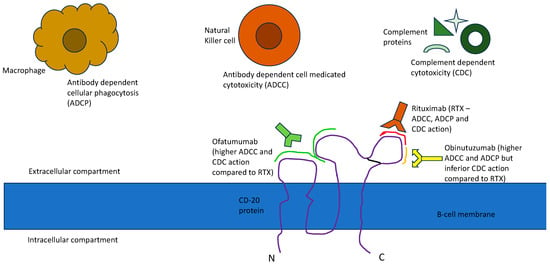

This led to the development of second-generation anti-CD20 antibodies like Ofatumumab, Ocrelizumab and Veltuzumab and third generation anti-CD20 antibodies like Obinutuzumab, Ocaratuzumab, EMAB-6 and Ublituximab. Ofatumumab was one of the first newer anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies to receive FDA approval for CLL. It is a second-generation, type 1 human IgG1k antibody [22]. It binds to a separate epitope from RTX, which includes a small extracellular loop and N terminal region of the second large extracellular loop, leading to greater binding avidity, which has been proposed to lead to enhanced ADCC [6]. Ofatumumab has also shown a better CDC than RTX, likely because it can bind closer to the cell membrane than RTX. Even with a low expression of CD20, the immune activity, its CDC particularly seems to be sustained [7]. Obinutuzumab is a third-generation humanized anti-CD20 antibody that has been FDA-approved for various lymphomas [16]. Obinutuzumab is an Fc-glycoengineered type 2 anti-CD20 antibody with greater direct cytotoxicity (believed to be caspase-independent) than RTX [8]. It has also shown superiority over RTX in ADCC and antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP) while being substantially inferior in its CDC, probably due to its C1q binding properties [9,23]. Figure 1 delineates the approval timeline of all three anti-CD20 antibodies in various lymphomas and Figure 2 depicts the binding of these antibodies to specific epitopes on the CD-20 receptor protein and their functional effects.

Figure 1. FDA approval timeline of anti-CD20 antibodies in various lymphomas.

Figure 2. CD20 epitope binding and functional effect of anti-CD20 antibodies.

3. Follicular Lymphoma (FL) and Other Indolent Non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (NHLs)

A phase 2 trial of an RTX monotherapy in 166 patients with R/R low-grade NHL demonstrated an objective response rate (ORR) of 48% and was well tolerated with manageable toxicity. This led to the regulatory approval of RTX by the US FDA [24]. Ofatumumab was compared with RTX in patients with FL and it failed to show superiority [10]. The GALLIUM phase 3 trial showed the superiority of Obinutuzumab over RTX in terms of its PFS and ORR. However, it also showed increased adverse events, including infusion reactions, compared to RTX [5].

A total of 46 patients with low-tumor burden FL after front-line RTX induction therapy were followed for 83.9 months. The median progression-free survival (mPFS) was 23.5 months and the median overall survival (mOS) was 91.7%. This trial showed that a majority of patients had a durable response to RTX [25]. A phase 3 trial evaluated rituximab maintenance therapy for up to 5 years after RTX induction in FL and showed that there was no difference in event-free survival (EFS) or OS [26]. RTX was evaluated in combination with CHOP therapy (R-CHOP) in 38 patients with treatment-naïve as well as previously treated low-grade NHL. The ORR was 100% and 87% achieved a complete response (CR). The median time to progression was 82.3 months. This study showed the substantial potential of RTX plus chemotherapy in low-grade NHL [27]. Another prospective study of R-CHOP vs. CHOP showed that the addition of RTX reduced the relative risk for treatment refractoriness by 60% (p < 0.001). The overall response rate was substantially higher (96% vs. 90%; p = 0.011) and a prolonged duration of remission (p = 0.001) was also noted [28].

Failure-free survival (FFS) is defined as the time interval between the reference date (date of randomization or date of diagnosis, etc.) and the date of progression/relapse at local, regional or metastatic sites. EFS is defined as the time from randomization until disease progression, not including surgery, local or distant recurrence, or death of any cause. The ECOG 1496 and PRIMA trials evaluated RTX maintenance therapy after induction with RTX plus chemotherapy in treatment-naïve FL and showed a significant increase in the 3-year PFS (ECOG 1496—64% vs. 33%; HR 0.4, p < 0.001), (PRIMA—74.9% vs. 57.6% HR 0.55, p < 0.001) [29,30]. The PFS benefit was sustained even after 6 years in the PRIMA study (59.2% vs. 42.7%; HR 0.58, p = 0.0001) [31].

RTX along with fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and mitoxantrone (FCM) showed superior responses in R/R FL compared to FCM alone in a phase 3 study [32]. Furthermore, maintenance with RTX led to a higher durability of the response [33]. A similar pattern was demonstrated in a phase 3 trial evaluating R-CHOP vs. CHOP, where the addition of RTX as part of induction therapy and subsequent maintenance therapy with RTX led to accentuated clinical outcomes in R/R FL [34]. An individual patient data meta-analysis evaluating RTX maintenance therapy included seven randomized trials with 2315 FL patients in total and showed that a higher OS was achieved compared to observation (HR 0.79, 95% CI 0.66–0.96) for all patients with FL except the subgroup which received RTX during induction [35]. The role of RTX in FL patients with a low disease burden compared to active surveillance remains to be determined [36]. A study by Sohani et al. evaluated tissue samples from four anti-CD20 therapy-based phase 2 trials and showed that interfollicular BCL6 positivity, interfollicular CD10 positivity and Ki67 ≥ 30% within neoplastic follicles was correlated with a worse PFS at 2 years.

A phase 1/2 study showed promising results for ofatumumab in RTX R/R FL with an ORR of 43% [37]. This prompted a phase 3 randomized controlled trial (RCT) (HOMER) comparing Ofatumumab to RTX in indolent B-cell NHLs that had relapsed after RTX-based therapy [10]. The patient population comprised RTX-sensitive relapsed FL that relapsed at least 6 months after completing the last treatment. The Ofatumumab arm had a shorter PFS (16.33 vs. 21.29 months; statistically not significant) and lower ORR (50% vs. 66%, not significant) compared to the RTX arm. IRR (2% vs. 0%, respectively), pneumonia (<1% vs. 2%, respectively) and sepsis (<1% vs. 1%, respectively) were the most frequently reported serious AEs (SAEs). IRRs (82% vs. 51%), infection-related AEs (32% vs. 37%), cardiac events (7% vs. 4%), neoplasms (6% vs. 3%) and mucocutaneous reactions (58% vs. 22%) were higher in the ofatumumab arm than the rituximab arm [10]. A recent single-center phase 1/2 trial studied Ofatumumab in combination with bendamustine, carboplatin and etoposide (BOCE) in 35 patients with relapsed/refractory NHL [38]. The ORR was 69% while the median PFS and OS were 5.1 and 26.2 months, respectively, with no treatment-related deaths. Twelve patients subsequently underwent allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (ASCT). The authors concluded BOCE to be a safe and effective outpatient regimen for R/R NHL patients while awaiting transplantation [38].

A phase 1 study involving 21 heavily pretreated R/R CD20+ indolent NHL showed encouraging results (5/21 CR; 4/21 PR; 43% ORR) for Obinutuzumab [39]. A randomized phase 2 study, GAUSS, compared Obinutuzumab to RTX in 175 patients with relapsed CD20+ indolent B-cell NHL (149 patients with FL histology and 26 patients with non-FL histology) [40]. The results showed an increased ORR (43.2% vs. 38.7% in FL and 43.2% vs. 35.6% overall) for Obinutuzumab compared to RTX without any additional safety concerns [40]. Another phase 2 study, GAUGUIN, evaluating obinutuzumab in 40 patients with R/R indolent NHL (34 patients with FL histology) also showed encouraging results (ORR 55%; mPFS 11.9 months) without additional safety concerns [41]. Together, these studies showed promising results for the use of obinutuzumab in FL. Another study, GAUDI, explored the safety and efficacy of obinutuzumab combined with chemotherapy (G-CHOP or G-FC) in 56 patients with R/R FL [42]. The ORR and CR for G-CHOP were 96% and 39%, respectively while they were 93% and 50%, respectively for G-FC [42]. Both regimens demonstrated an acceptable safety profile with no new AEs detected [42]. This led to the phase 3 RCT, GALLIUM, comparing 1000 mg Obinutuzumab vs. 375 mg/m2 RTX plus chemotherapy as the first-line therapy in 1202 patients with FL [5]. At a median follow-up of 34.5 months, obinutuzumab showed superiority over RTX (ORR 88.5% vs. 86.9%; 3-year PFS 80.0% vs. 73.3%; and HR for progression, relapse, or death of 0.66) [5]. This study paved the way for its approval as the first-line in FL [11]. Grade 3–5 AEs (68% vs. 62%), serious AEs (38% vs. 32%) and IRR (11% vs. 6%) were higher in the obinutuzumab group. AEs leading to the cessation of treatment occurred in 97 patients (16.3%) in the Obinutuzumab group in comparison to 85 (14.2%) patients in the rituximab group [43]. Another phase 3 open-label RCT, GADOLIN, compared obinutuzumab plus bendamustine vs. bendamustine in RTX refractory indolent NHL [43]. The obinutuzumab arm showed an improved mPFS with an HR of 0.55 [43]. The final analysis from the GALLIUM trial showed that after a median of 7.9 years of follow-up, PFS was higher with obinutuzumab plus chemotherapy vs. rituximab-based therapy, with 7-year PFS rates of 63.4% vs. 55.7%, respectively (p = 0.006). Serious adverse events were slightly higher with obinutuzumab (48.9%) compared to rituximab (43.4%). However, the rates of adverse events culminating in fatality were similar (4.4% and 4.5%, respectively). These data consolidated the long-term benefit of obinutuzumab-based therapy and reaffirmed its role as a standard of care for the first-line management of advanced FL [44].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/lymphatics2010002

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!