A warning sign for impending cardiovascular events is not fully established. In the process of plaque rupture, the formation of vulnerable plaque is important, and oxidized cholesterols play an important role in its progression. Furthermore, the significance of vasa vasorum penetrating the medial smooth muscle layer and being rich in atheromatous lesions should be noted. The cardio-ankle vascular index (CAVI) is a new arterial stiffness index of the arterial tree from the origin of the aorta to the ankle. The CAVI reflects functional stiffness, in addition to structural stiffness. The rapid rise in the CAVI means medial smooth muscle cell contraction and strangling vasa vasorum. A rapid rise in the CAVI in people after a big earthquake, following a high frequency of cardiovascular events has been reported.

- cholesterol oxidative products

- atheromatous lesion

- plaque rupture

- vasa vasorum

- cardio-ankle vascular index

1. Introduction

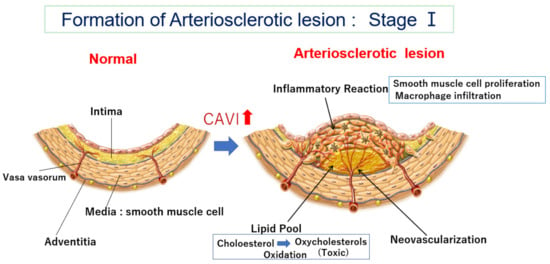

2. Reconsideration concerning the Formation of Vulnerable Plaque

2.1. The Formation of the Lipid Pool in the Intima of the Arterial Wall

2.2. How Does the Lipid Pool Developed in the Intima Make Progress to Vulnerable Plaque—The Role of Oxidized Cholesterol for Provoking Inflammatory Reaction

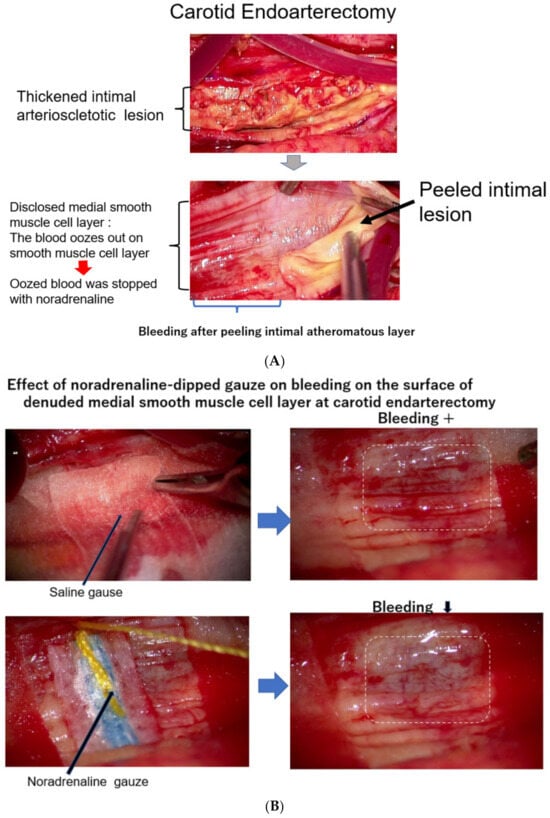

2.3. Neovascularization of Vasa Vasorum in the Arterial Wall

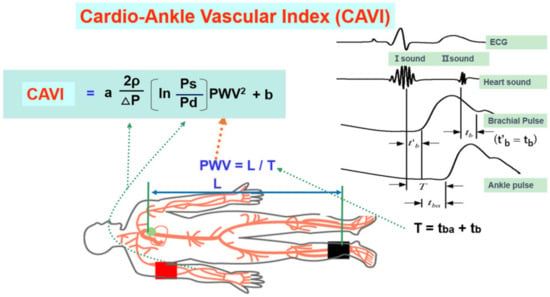

3. The Meaning of a Rapid Increase in the CAVI

3.1. What Is the CAVI?

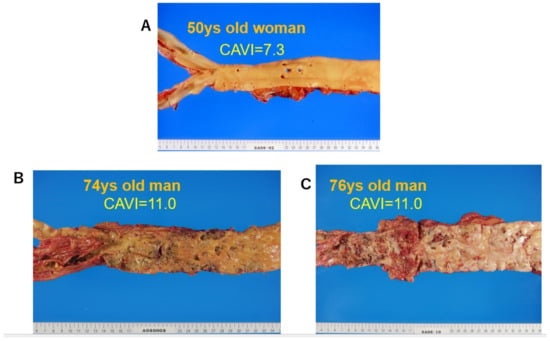

3.2. The CAVI Reflects the Degree of Atherosclerosis

3.3. The CAVI Also Reflects the Functional Stiffness of the Artery

3.4. The CAVI Just after a Huge Natural Disaster and Stress

3.5. Smooth Muscle Cell Contraction Hypothesis for Plaque Rupture: The Role of Rapid Rise in the CAVI

4. Treatments to Improve the CAVI

- (1)

-

Lifestyle changes

- (2)

-

Controlling high blood pressure

- (3)

-

Control of diabetic mellitus

- (4)

-

Among lipid-lowering agents

- (5)

-

Health supplements

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/jcm12237436

References

- Roth, G.A.; Johnson, C.; Abajobir, A.; Abd-Allah, F.; Abera, S.F.; Abyu, G.; Ahmed, M.; Aksut, B.; Alam, T.; Alam, K.; et al. Global, Regional, and National Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases for 10 Causes, 1990 to 2015. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2017, 70, 1–25.

- Anitschkow, N.; Chalatow, S. Ueber experimentelle cholesterinsteatose und ihre bedeutung für die entstehung einiger pathologischer prozesse. Zentralbl. Allg. Pathol. Anat. 1913, 24, 1–9. (In German)

- Goldstein, J.L.; Brown, M.S. A century of cholesterol and coronaries: From plaques to genes to statins. Cell 2015, 161, 161–172.

- Steinberg, D.; Witztum, J.L. History of discovery: Oxidized low-density lipoprotein and atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2010, 30, 2311–2316.

- Brown, M.S.; Goldstein, J.L. Lipoprotein metabolism in the macrophage: Implications for cholesterol deposition in atherosclerosis. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 1983, 52, 223–261.

- Ross, R.; Glomset, J. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 1976, 295, 420–425.

- Muller, J.E.; Tofler, G.H.; Stone, P.H. Circadian variation and triggers of onset of acute cardiovascular disease. Circulation 1989, 79, 733–743.

- Libby, P.; Pasterkamp, G.; Crea, F.; Jang, I.K. Reassessing the Mechanisms of Acute Coronary Syndromes. The “Vulnerable Plaque” and Superficial Erosion. Circ. Res. 2019, 124, 150–160.

- Vejux, A.; Lizard, G. Cytotoxic effects of oxysterols associated with human diseases: Induction of cell death (apoptosis and/or oncosis), oxidative and inflammatory activities, and phospholipidosis. Mol Aspects Med. 2009, 30, 153–170.

- Shiomi, M. The History of the WHHL Rabbit, an Animal Model of Familial Hypercholesterolemia (I)—Contribution to the Elucidation of the Pathophysiology of Human Hypercholesterolemia and Coronary Heart Disease. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2020, 27, 105–118.

- Otsuka, F.; Kramer, M.C.; Woudstra, P.; Yahagi, K.; Ladich, E.; Finn, A.V.; de Winter, R.J.; Kolodgie, F.D.; Wight, T.N.; Davis, H.R.; et al. Natural Progression of Atherosclerosis from Pathologic Intimal Thickening to Late Fibroatheroma in Human Coronary Arteries: A Pathology Study. Atherosclerosis 2015, 241, 772–782.

- Abumrad, N.A.; Cabodevilla, A.G.; Samovski, D.; Pietka, T.; Basu, D.; Goldberg, I.J. Endothelial Cell Receptors in Tissue Lipid Uptake and Metabolism. Circ. Res. 2021, 5, 433–450.

- Dabagh, M.; Jalali, P.; Tarbell, J.M. The transport of LDL across the deformable arterial wall: The effect of endothelial cell turnover and intimal deformation under hypertension. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2009, 297, H983–H996.

- Williams, J.K.; Heistad, D.D. The vasa vasorum of the arteries. J. Mal. Vasc. 1996, 21 (Suppl. C), 266–269. (In French)

- Camaré, C.; Pucelle, M.; Nègre-Salvayre, A.; Salvayre, R. Angiogenesis in the atherosclerotic plaque. Redox Biol. 2017, 12, 18–24.

- Subbotin, V.M. Neovascularization of coronary tunica intima (DIT) is the cause of coronary atherosclerosis. Lipoproteins invade coronary intima via neovascularization from adventitial vasa vasorum, but not from the arterial lumen: A hypothesis. Theor. Biol. Med. Model. 2012, 9, 11.

- Brown, A.J.; Jessup, W. Oxysterols and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 1999, 142, 1–28.

- Poli, G.; Sottero, B.; Gargiulo, S.; Leonarduzzi, G. Cholesterol oxidation products in the vascular remodeling due to atherosclerosis. Mol. Aspects. Med. 2009, 30, 180–189.

- Garcia-Cruset, S.; Carpenter, K.L.; Guardiola, F.; Stein, B.K.; Mitchinson, M.J. Oxysterol profiles of normal human arteries, fatty streaks and advanced lesions. Free Radic. Res. 2001, 35, 31–41.

- Griffiths, W.J.; Yutuc, E.; Abdel-Khalik, J.; Crick, P.J.; Hearn, T.; Dickson, A.; Bigger, B.W.; Hoi-Yee Wu, T.; Goenka, A.; Ghosh, A.; et al. Metabolism of Non-Enzymatically Derived Oxysterols: Clues from sterol metabolic disorders. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 144, 124–133.

- Brown, A.J.; Watts, G.F.; Burnett, J.R.; Dean, R.T.; Jessup, W. Sterol 27-hydroxylase acts on 7-ketocholesterol in human atherosclerotic lesions and macrophages in culture. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 27627–27633.

- Oyama, T.; Miyashita, Y.; Kinoshita, K.; Watanabe, H.; Shirai, K.; Yagima, T. Effect of deposited lipids in atheromatous lesions on the migration of vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2002, 9, 109–113.

- Ravi, S.; Duraisamy, P.; Krishnan, M.; Martin, L.C.; Manikandan, B.; Raman, T.; Sundaram, J.; Arumugam, M.; Ramar, M. An insight on 7- ketocholesterol mediated inflammation in atherosclerosis and potential therapeutics. Steroids 2021, 172, 108854.

- Amaral, J.; Lee, J.W.; Chou, J.; Campos, M.M.; Rodríguez, I.R. 7-Ketocholesterol induces inflammation and angiogenesis In Vivo: A novel rat model. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e56099.

- Zimetbaum, P.; Eder, H.; Frishman, W. Probucol: Pharmacology and clinical application. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1990, 30, 3–9.

- Chistiakov, D.A.; Melnichenko, A.A.; Myasoedova, V.A.; Grechko, A.V.; Orekhov, A.N. Role of lipids and intraplaque hypoxia in the formation of neovascularization in atherosclerosis. Ann. Med. 2017, 49, 661–677.

- Shimizu, K.; Takahashi, M.; Sato, S.; Saiki, A.; Nagayama, D.; Harada, M.; Miyazaki, C.; Takahara, A.; Shirai, K. Rapid Rise of Cardio-Ankle Vascular Index May Be a Trigger of Cerebro-Cardiovascular Events: Proposal of Smooth Muscle Cell Contraction Theory for Plaque Rupture. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2021, 17, 37–47.

- Laurent, S.; Cockcroft, J.; Van Bortel, L.; Boutouyrie, P.; Giannattasio, C.; Hayoz, D.; Pannier, B.; Vlachopoulos, C.; Wilkinson, I.; Struijker-Boudier, H. Expert consensus document on arterial stiffness: Methodological issues and clinical applications. Eur. Heart J. 2006, 27, 2588–2605.

- Yamashina, A.; Tomiyama, H.; Takeda, K.; Tsuda, H.; Arai, T.; Hirose, K.; Koji, Y.; Hori, S.; Yamamoto, Y. Validity, reproducibility, and clinical significance of noninvasive brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity measurement. Hypertens. Res. 2002, 25, 359–364.

- Nye, E.R. The effect of blood pressure alteration on the pulse wave velocity. Br. Heart J. 1964, 266, 261–265.

- Shirai, K.; Utino, J.; Otsuka, K.; Takata, M. A novel blood pressure-independent arterial wall stiffness parameter; cardio-ankle vascular index (CAVI). J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2006, 13, 101–107.

- Hayashi, K.; Handa, H.; Nagasawa, S.; Okumura, A.; Moritake, K. Stiffness and elastic behavior of human intracranial and extracranial arteries. J. Biomech. 1980, 13, 175–184.

- Bramwell, J.C.; Hill, A.V. Velocity of the pulse wave in man. Proc. Roy. Soc. B: Biol. 1922, 93, 298–306.

- Shirai, K.; Song, M.; Suzuki, J.; Kurosu, T.; Oyama, T.; Nagayama, D.; Miyashita, Y.; Yamamura, S.; Takahashi, M. Contradictory effects of β1- and α1-aderenergic receptor blockers on cardio-ankle vascular stiffness index (CAVI)—The independency of CAVI from blood pressure. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2011, 18, 49–55.

- Saiki, A.; Ohira, M.; Yamaguchi, T.; Nagayama, D.; Shimizu, N.; Shirai, K.; Tatsuno, I. New Horizons of Arterial Stiffness Developed Using Cardio-Ankle Vascular Index (CAVI). J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2020, 8, 732–748.

- Yamamoto, T.; Shimizu, K.; Takahashi, M.; Tatsuno, I.; Shirai, K. The Effect of Nitroglycerin on Arterial Stiffness of the Aorta and the Femoral-Tibial Arteries. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2017, 10, 1048–1057.

- Nagayama, D.; Imamura, H.; Endo, K.; Saiki, A.; Sato, Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; Watanabe, Y.; Ohira, M.; Shirai, K.; Tatsuno, I. Marker of Sepsis Severity is Associated with the Variation in Cardio-Ankle Vascular Index (CAVI) During Sepsis Treatment. Vasc. Health Risk Manag. 2019, 15, 509–516.

- Kario, K.; Matsuo, T.; Kobayashi, H.; Yamamoto, K.; Shimada, K. Earthquake-induced potentiation of acute risk factors in hypertensive elderly patients: Possible triggering of cardiovascular events after a major earthquake. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1997, 29, 926–933.

- Trichopoulos, D.; Zavitsanos, X.; Katsouyanni, K.; Tzonou, A.; Dalla-Vorgia, P. Psychological stress and fatal heart attack: The Athens (1981) earthquake natural experiment. Lancet 1983, 321, 441–444.

- Dobson, A.J.; Alexander, H.M.; Malcolm, J.A.; Steele, P.L.; Miles, T.A. Heart attacks and the Newcastle earthquake. Med. J. Aust. 1991, 155, 757–761.

- Leor, J.; Poole, W.K.; Kloner, R.A. Sudden cardiac death triggered by an earthquake. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 334, 413–419.

- Nakagami, T.; Shimizu, K.; Hirano, K.; Kiyokawa, H.; Iwakawa, M.; Ikeda, Y.; Akiba, T.; Terayama, K.; Ogawa, A.; Shirai, K. Cardio-Ankle Vascular Index Reflects the Efficacy of Waon Therapy in Heart Failure Patients. Int. Heart J. 2022, 63, 1092–1098.