There is a diversity of socio-economic status among residents in Bangkok in the use of electricity for their living and small businesses with different tariffs. Households in Bangkok have a positive attitude toward and are willing to pay for renewable energy (RE), including solar cells, wind, and hydropower, except for biomass, as they are not sure of its level of eco-friendliness. They all have a unique opinion that providing a good quality of power is under the responsibility of the Government, as it is for the welfare and the right to have a quality power service, so they do not need to pay more for a better one.

1. Introduction

In the twenty-first century, electric power has become the most important source of energy for daily living. According to the growth of global electricity consumption, per capita electricity consumption in developing countries will double by 2030, reaching nearly 2400 kWh per person, while developed countries will increase by 7% (

European Environment Agency 2015). Electricity is a secondary resource generated from a mix of natural sources for electricity production. Unlike renewable resources, they are finite and will deplete over time. Therefore, a continuous and consistent supply must be maintained to meet our energy needs. The degree of willingness to pay (WTP) for renewable energy is an important indicator of how to respond to increased renewable installations (

REI 2020).

Thailand’s power system is characterized by a high proportion of natural gas-fired production capacity (about 60% of installed capacity), hydropower generation with storage, and a minor proportion of variable renewable energy, less than 4 percent. (

IRENA 2017). Based on that small percentage, the total solar power output is 19–20 MJ/m

2 per day. Thailand is now ranked fourth out of six countries, trailing only the United States of America (

Ministry of Energy 2015). The Alternative Energy Development Plan (AEDP) policy for the period 2015 to 2036 seeks to construct an extra 7.5 gigawatts (GW) of variable RE capacity by 2036, primarily from solar photovoltaics, to meet Thailand’s peak energy demand of roughly 30 GW in 2015 (

DEDE 2021). It is necessary to create an incentive scheme in Thailand that allows companies to generate renewable energy and purchase it back from the government’s electric authority at a discounted rate known as Adder (feed-in premium), making Thai entrepreneurs interested in renewable energy, particularly solar energy. As a result, several new vendors have sprung up in Thailand (

Suanmali et al. 2018).

Energy Situation in Thailand

As previously stated, a significant component of Thailand’s power system is based on natural gas-fired electrical generation, with a tiny fraction based on renewable energy. Thailand’s latest Power Development Plan (2018) intends to expand the amount of generating capacity powered by renewable energy sources to 36% by 2037. Due to technological advancements and quick cost reductions, the country is seeing a strong uptake of variable renewable energy (VRE), notably solar PV (

Tongsopit and Greacen 2013). Thailand is also regarded as a REIa leader in the field of renewable energy development. Thailand was one of the first Asian countries to use a feed-in tariff (FIT) system. When premium rates are placed on top of wholesale power prices, the FIT, also known as the Adder Program, entered into force in 2007. In 2013, the plan was changed to a fixed FIT (

UNESCAP 2020). The continuous rise of renewable energy in its power mix has been observed in recent years as a result of well-balanced and responsive regulations (

Malahayati 2020).

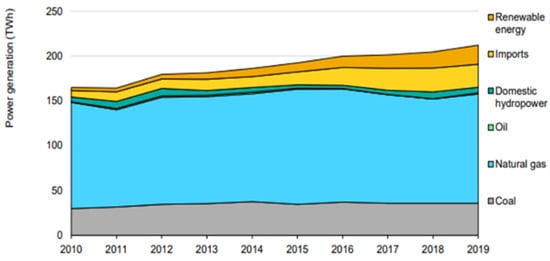

Noted: Imports encompass foreign hydropower and lignite, while renewable energy sources include wind, solar PV, and bioenergy. These data sources are derived from the Energy Policy and Planning Office (2020) and EGATs Electricity reports.

As depicted in Figure 1, natural gas has maintained its position as the predominant source of power generation in Thailand over the past two decades. It constituted approximately 70% of the total power generation in the early 2000s. The generating mix has gotten increasingly diverse in recent years, with the percentage of renewables and imports growing in 2019. Renewable energy’s percentage of overall generation has consistently climbed in recent years, going from 12% in 2017 to nearly 20 percent in 2019. Hydropower (both local and imported) accounts for the majority of renewable energy, with solar and wind power accounting for around 4% of total output.

Figure 1. Thailand’s power generation by fuel type, 2010–2019 (

IEA 2021b).

Despite Thailand’s steady progress and its emerging leadership in the field of renewable energy (RE), the country continues to exhibit a significant dependence on oil and natural gas. The Thai government has taken proactive measures to rectify this situation, including the introduction of the Alternative Energy Development Plan (AEDP), aimed at boosting the utilization of renewable energy sources. Additionally, the 20-Year Power Development Plan 2010–2030 outlines an ambitious target to reduce gas consumption by approximately 12.6% by 2030 while simultaneously promoting the adoption of more renewable energy sources and nuclear power (

Malahayati 2020). Thailand, as a middle-income country, mostly allocates budgets for economic development, including the supply of water and electricity for several economic activities such as agriculture, industry, tourism, and SMEs (

Nitivattananon and Sa-nguanduan 2013). To respond to the intention of the Thai government, it is necessary to realize the acceptance cost and price of adapting the RE at the household level. The benefit of recognizing this data are that it will assist policymakers and the government in planning and issuing strategies to increase the trend of RE use; it becomes potential bottom-line data.

2. Pay for Renewable Energy Alternatives Willingness in Thailand

WTP measurement is a valuable tool in economics and market research that helps assess the value individuals or consumers place on a particular product, service, or attribute. It helps in devising effective pricing strategies by understanding what customers are willing to pay. Companies can set prices that are competitive yet profitable, and they can tailor pricing to different market segments. Meanwhile, the price of electricity in Thailand varies depending on the Government. Thailand’s trajectory is progressively inclining, positioning itself as a prominent figure in the realm of renewable energy (RE). The Thai government has unveiled the Alternative Energy Development Plan (AEDP) as a strategic initiative aimed at augmenting the utilization of renewable energy sources. Furthermore, the 20-Year Power Development Plan for the period 2010–2030 has been established with the overarching goal of diminishing the nation’s reliance on natural gas by approximately 12.6% by the year 2030 while concurrently fostering the integration of a diversified portfolio of renewable energy resources. However, it is important to note that accurately measuring WTP can be challenging, and the results may vary depending on the methodology and context of the RE situation in Thailand. Moreover, there was one article that used the same tools and method to find WTP for renewable energy in Myanmar. The result found that people in Myanmar were willing to pay for renewable energy for each type of renewable electric power generation source. Global advancements in the adoption of solar power have paralleled the recent decline in prices, as noted by Numata et al. in 2021.

The empirical results of socio-economic exploration found a diversity of residential status in Bangkok. The Metropolitan Electricity Authority (MEA) was the main and only organization to provide electricity to households in Bangkok. It seems the state has a monopoly, in which people do not have choices for electricity service and still face power outages 3.6 times per year on average. It was not surprising why the household respondents have a positive attitude toward RE as there are more choices (Solar Cell 96%, Wind Power 78%, Biomass 58.4%, and Hydro Power 72.4%), even if they realize that their electricity bill will increase. Also, the household respondents have the opinion that providing a good quality of power is under the responsibility of the Government, it is for the welfare and the right to have a quality power service. Finally, the households in metropolitan areas have cognition on environmental problems such as air pollution and climate change (agree level at 33.6%); however, they still chose to use the existing status of electricity production and remain unchanged to apply RE generally.

Earlier research conducted among Bangkok residents showed little support for the ban on burning solid fuels and oil. The Thai government endeavored to address this pattern by introducing the Alternative Energy Development Plan (AEDP), which aimed to boost the renewable energy (RE) portion to 36% and incorporate nuclear power into the 20-Year Power Development Plan 2010–2030, as outlined in Malahayati’s 2020 report. To increase the adaptation of RE at the household level, the Government needs to support the specific source of households’ preferences. Even if the share of electric power was not much, solar power was still the highest preference among others; the WTP values of solar cells were 5.54%. It can increase gradually to the bottom-line RE use, pushing toward the national level of RE use, respectively.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/socsci12110634