Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Urethral mesh placement has become a common surgical intervention for the management of stress urinary incontinence. While this procedure offers significant benefits, it is not without potential complications. By understanding the spectrum of normal findings of urethral mesh and the possible complications, clinicians can improve patient outcomes and make inf

- mesh

- urethral mesh

- TOT

- TVT

- urethral neoplasm

1. Urethral Mesh in Oncological Patients

There are several types of malignancies that may involve the pelvic structures, such as gynecological cancer (ovarian, cervical, endometrial), rectal or bladder cancer and other rarer causes and mimickers. For ease of reading, we will refer to all of them below as “pelvic cancers”. Surgical techniques along with radiotherapy and chemotherapy have increased the survival of patients with pelvic cancers, while increasing the importance of their quality of life (QOL) [1][2][3][4].

Urinary incontinence and overactive bladder are both pathological conditions that have a high prevalence after pelvic surgery and are known to greatly impair QOL. Urinary incontinence particularly affects women, causing adverse physical, emotional, and social effects [5][6]. The prevalence of urinary incontinence after a pelvic surgery for cancer, ranges between 24–52.4% [7][8], with no reported differences regarding the primary cancer site.

There are two categories of patients with urethral meshes: (1) patients with mesh who may develop a pelvic cancer, and (2) patients with a pelvic cancer and post-surgical urinary incontinence treated with urethral meshes.

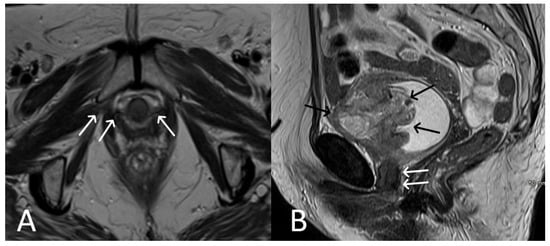

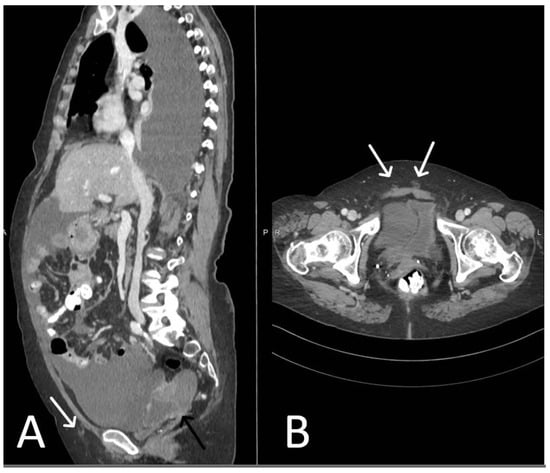

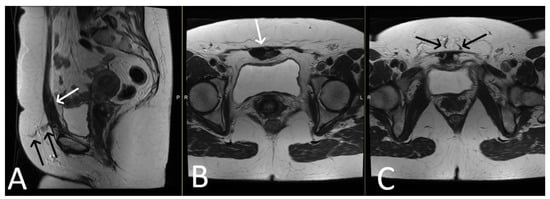

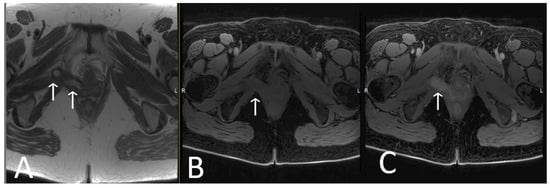

For the first category of the patients, in addition to highlighting tumour invasion into adjacent structures, MRI is able to highlight how the cancer affects the urethral mesh, its location, structure and possible complications (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 1. Patient with bladder cancer and TOT mesh. Axial (A) and sagittal (B) T2WI images demonstrate extensive abnormal soft tissue of the anterior aspect of bladder (black arrows) in the setting of a normal TOT (white arrows).

Figure 2. Patient with ovarian cancer and TVT mesh. Sagittal (A) and axial (B) contrast enhanced CT showing a mixed cystic-solid ovarian mass (black arrow), ascites and pleural effusion. Normal TVT is visible in both planes (white arrows).

Figure 3. Desmoid tumour of the anterior abdominal wall, with TVT mesh. Sagittal (A) and axial (B,C) T2WI demonstrate low T2 signal desmoid tumour of the anterior abdominal wall (white arrows). Normal appearance of the TVT seen passing through the inferior aspect of the desmoid tumour (black arrows).

For the second category of patients treated for a pelvic cancer, MRI is usually used to detect tumour recurrence and short- and long-term mesh complications.

2. Urethral Mesh Complications

Complications associated with urethral mesh procedures can occur, but their frequency can vary depending on several factors, including the specific procedure, patient characteristics (including the onset of a pelvic cancer), and the experience of the surgeon. It is important to note that the complication rates can vary depending on the length of follow-up and the definition and reporting of complications across different studies [9]. However, it is generally accepted that two main types of complications can occur: short-term and long-term, both of which also affect cancer patients.

2.1. Short-Term Complications

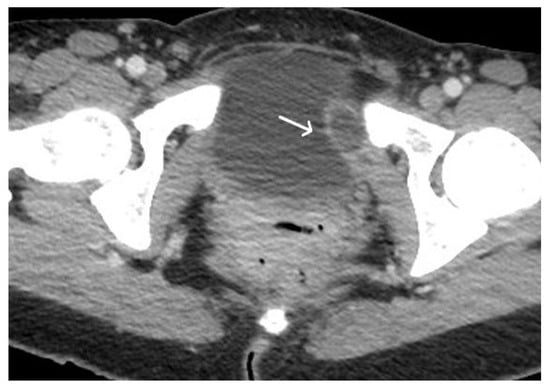

Short-term complications include intraoperative and immediate post-operative complications related to injuries during surgery, acute urinary retention and infections [10][11]. Depending on the mesh pathway we may encounter bladder, urethral or bowel injuries in up to 24% of the TVT, and obturator nerve and artery lesions in up to 2% of the TOT patients [12] (Figure 4, Figure 5 and Figure 6).

Figure 4. Acute haematoma post TVT procedure. Post-contrast CT imaging is highlighting a well-defined collection (white arrow) in left obturator internus muscle; no signs of active bleeding are noted.

Figure 5. Acute pelvic haematoma post sacrohysteropexy. Post-contrast CT imaging demonstrates a large, well-defined and hyperdense collection (haematoma) located within the pelvis, with important mass effect on the bladder and rectum; no signs of active bleeding are noted.

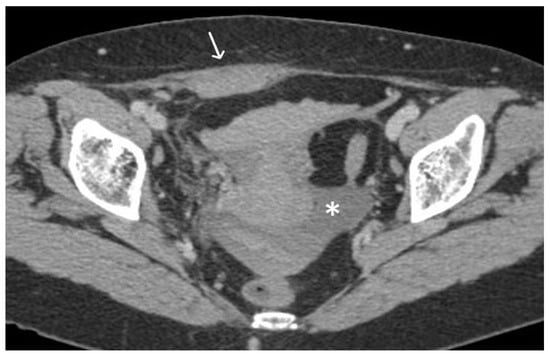

Figure 6. Haemoperitoneum and right rectus sheath haematoma post sacro-hysteropexy. Post-contrast CT imaging demonstrates hyperdense free fluid (*) located in the pelvic peritoneal reflection suggestive of haemoperitoneum and a well-defined hyperdense collection (white arrow) located within the right rectus abdominal muscle consistent with a haematoma; no signs of active bleeding are noted.

The reported rates of acute urinary retention (AUR) following urethral mesh placement have ranged from between 2% to 12% [13][14][15]. However, it’s important to remember that these rates can vary depending on the specific procedure, patient population, the follow-up period of the study and different causes. Several factors can contribute to the development of AUR, such as post-operative swelling, overactive bladder, temporary dysfunction of the bladder muscle or nerves, excessive mesh tension or malpositioned tape sitedtoward the urethra-vesical junction. It is worth mentioning that AUR is often a transient complication and can be managed with conservative measures, the temporary use of a catheter and only in a minority of cases is surgery required.

It is important to note that the occurrence of infection can be influenced by factors such as the patient’s overall health, pre-existing conditions, adherence to sterile techniques during surgery, and post-operative care.

The reported rates of infections in the early post-operative period following urethral mesh procedures have ranged from less than 1% to around 10% [16][17]. Infections can manifest as urinary tract infections (UTIs) or surgical site infections. UTIs are more common, present with symptoms such as increased urinary frequency, urgency, burning sensation during urination, lower abdominal/ pelvic discomfort and have a conservative treatment. Surgical site infections can cause redness, swelling, warmth, pain, or discharge at the incision site and usually require imaging to assess the depth and the local extent of the disease (Figure 7).

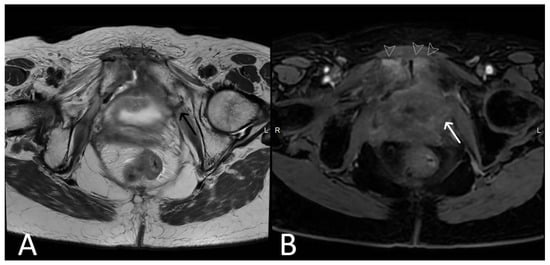

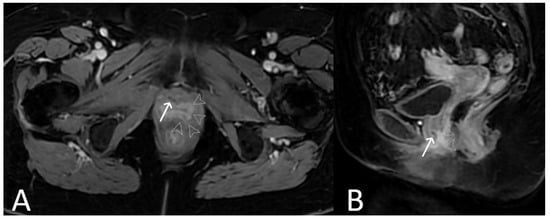

Figure 7. History of cervical cancer, TOT in situ and pubic symphysis osteomyelitis. Axial T2WI (A) and T1 fat saturated, post contrast (B) sequences demonstrate thickened left limb of TOT traversing obturator foramen to adductor muscles (black arrow), with post-contrast enhancement (white arrow) sugestive of infection. Enhancement at the pubic symphysis (white arrowheads) with loss of normal low T1 and T2 signal of the cortex (black arrowheads) consistent with osteomyelitis.

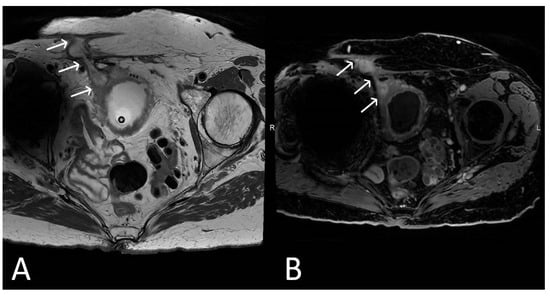

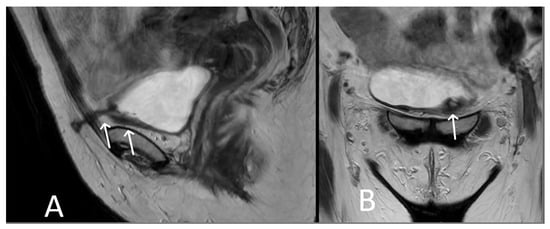

Inflammation and infections of urethral meshes are easily depicted on thin T2WI slices, as having thickened uni- or bilateral limbs with high signal intensity. Abscesses may affect any portion of the mesh and therefore requires evaluation of the trajectory of the mesh in all planes. Infected or inflammed mesh appears with avid enhancement on post-contrast sequences, helping identifing the sinus trast and abscesses (Figure 8 and Figure 9).

Figure 8. Upper images: Complicated, infected right limb of TVT and bladder erosion. Axial T2WI (A) and T1 fat saturated, post contrast (B) sequences demonstrate TVT with abscess of right limb, extending from the bladder wall to the skin surface in keeping with a sinus tract (white arrows) due to a bladder erosion. Lower images: Complicated, infected right limb of TVT. Coronal (C) and axial (D) T2WI sequences demonstrate thickened right limb of TVT within bladder wall (white arrows). Extension to skin partially visualised on axial sequence (black arrow). Artefact from right hip prosthesis.

Figure 9. Infected limb of TOT and vaginal exposure. Axial T2WI (A), T1 fat saturated (B), and T2 fat saturated, post contrast (C) sequences of TOT demonstrate marked thickening and avid post contrast enhancement of infected right limb of mesh (white arrows), most likely due to a vaginal exposure.

2.2. Long-Term Complications

Delayed-postoperative complications range from 3–25% of cases and include bladder outlet obstruction, urinaryx incontinence and recurrent urinary tract infections in the majority of the cases; while only 2–3% of these are related to mesh integrity and/or abnormal localization [16][17][18]. Of the latter, the most common complications are mesh exposure/erosion and extrusion, and may lead to reccurent urinary infections or irritative pelvic simptoms. Whenever a mesh lesion is clinically suspected, we suggest performing a dedicated MRI for assessing mesh integrity, while also acknowledging the potential utility of ultrasound.

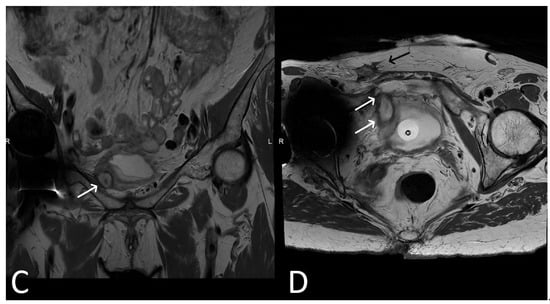

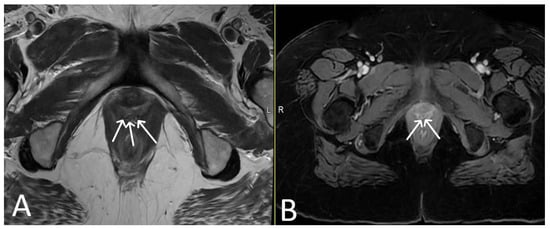

Erosion or exposure of the mesh usually involve vagina, urethra or bladder, and are recognised when the mesh limbs are seen within the lumen of these sturctures [19]. The involved mesh limb will be thicknened with high T2WI signal intensity and mild- to avid- enhancement on post contrast sequences.

In many cases, inflammation and infection occurring late after surgery secondary to mesh erosion, particularly involving the vagina. Surgery may be needed to remove the affected limb or entire mesh or correct other complications, although the overall incidence is rare. Over 50% of women who experienced erosion with non-absorbable synthetic mesh needed to have the mesh surgically removed. Some patients required two or more operations after the mesh was removed (Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13).

Figure 10. Bladder erosion. Sagittal (A) and coronal (B) T2WI showing left arm of TVT passing through the left anterolateral bladder wall (white arrows). The bladder wall is markedly thickened at this site with irregularity and oedema of the adjacent urothelium.

Figure 11. Urethral erosion. Axial (A) and sagittal (B) T1 fat saturated post-contrast sequences, demonstrating linear low signal within urethra (white arrows), reflecting erosion of mesh into the urethra. There is enhancement of the lower urethra and vagina (arrowheads). Cystoscopy confirmed synthetic fibres within urethral lumen, which were resected.

Figure 12. Vaginal exposure. (Same patient). Axial T2WI (A) and axial fat saturated post-contrast T1 (B) images. Linear low signal intensity mesh within the oedematous vagina, compatible with mesh exposure (white arrows).

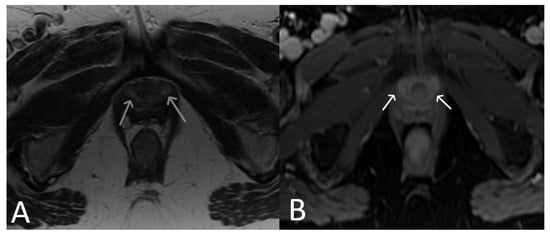

Figure 13. Normal clinical examination. Inflammation without mesh erosion. Axial T2WI (A) and axial fat saturated post-contrast T1WI (B) demonstrating abnormal high/intermediate T2 signal intensity of mesh as it passes between the vagina and urethra (grey arrows). On post contrast imaging, this portion of the mesh demonstrates avid enhancement (white arrows).

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/cancers15235599

References

- Patel, T.; Sugandh, F.; Bai, S.; Varrassi, G.; Devi, A.; Khatri, M.; Kumar, S.; Dembra, D.; Dahri, S. Single Incision Mini-Sling Versus Mid-Urethral Sling (Transobturator/Retropubic) in Females with Stress Urinary Incontinence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus 2023, 15, e37773.

- Bifulco, G.; De Rosa, N.; Tornesello, M.L.; Piccoli, R.; Bertrando, A.; Lavitola, G.; Morra, I.; Di Spiezio Sardo, A.; Buonaguro, F.M.; Nappi, C. Quality of life, lifestyle behavior and employment experience: A comparison between young and midlife survivors of gynecology early stage cancers. Gynecol. Oncol. 2012, 124, 444–451.

- Alahmadi, R.; Steffens, D.; Solomon, M.J.; Lee, P.J.; Austin, K.K.S.; Koh, C.E. Elderly Patients Have Better Quality of Life but Worse Survival Following Pelvic Exenteration: A 25-Year Single-Center Experience. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2021, 28, 5226–5235.

- Stanca, M.; Căpîlna, D.M.; Căpîlna, M.E. Long-Term Survival, Prognostic Factors, and Quality of Life of Patients Undergoing Pelvic Exenteration for Cervical Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 2346.

- Aoki, Y.; Brown, H.W.; Brubaker, L.; Cornu, J.N.; Daly, J.O.; Cartwright, R. Urinary incontinence in women. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2017, 3, 17042.

- Radzimińska, A.; Strączyńska, A.; Weber-Rajek, M.; Styczyńska, H.; Strojek, K.; Piekorz, Z. The impact of pelvic floor muscle training on the quality of life of women with urinary incontinence: A systematic literature review. Clin. Interv. Aging 2018, 13, 957–965.

- Hazewinkel, M.H.; Sprangers, M.A.; van der Velden, J.; van der Vaart, C.H.; Stalpers, L.J.; Burger, M.P.; Roovers, J.P. Long-term cervical cancer survivors suffer from pelvic floor symptoms: A cross-sectional matched cohort study. Gynecol. Oncol. 2010, 117, 281–286.

- Nakayama, N.; Tsuji, T.; Aoyama, M.; Fujino, T.; Liu, M. Quality of life and the prevalence of urinary incontinence after surgical treatment for gynecologic cancer: A questionnaire survey. BMC Women’s Health 2020, 20, 148.

- Novara, G.; Galfano, A.; Boscolo-Berto, R.; Secco, S.; Cavalleri, S.; Ficarra, V.; Artibani, W. Complication rates of tension-free midurethral slings in the treatment of female stress urinary incontinence: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing tension-free midurethral tapes to other surgical procedures and different devices. Eur. Urol. 2008, 53, 288–308.

- Gomes, C.M.; Carvalho, F.L.; Bellucci, C.H.S.; Hemerly, T.S.; Baracat, F.; de Bessa, J., Jr.; Srougi, M.; Bruschini, H. Update on complications of synthetic suburethral slings. Int. Braz. J. Urol. 2017, 43, 822–834.

- Barisiene, M.; Cerniauskiene, A.; Matulevicius, A. Complications and their treatment after midurethral tape implantation using retropubic and transobturator approaches for treatment of female stress urinary incontinence. Videosurg. Other Miniinvasive Tech. 2018, 13, 501–506.

- LaSala, C.A. Incomplete bladder emptying after the tension-free vaginal tape procedure, necessitating release of the mesh. A report of three cases. J. Reprod. Med. 2003, 48, 387–390.

- Klutke, C.; Siegel, S.; Carlin, B.; Paszkiewicz, E.; Kirkemo, A.; Klutke, J. Urinary retention after tension-free vaginal tape procedure: Incidence and treatment. Urology 2001, 58, 697–701.

- Petri, E.; Ashok, K. Complications of synthetic slings used in female stress urinary incontinence and applicability of the new IUGA-ICS classification. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2012, 165, 347–351.

- Karsenty, G.; Boman, J.; Elzayat, E.; Lemieux, M.C.; Corcos, J. Severe soft tissue infection of the thigh after vaginal erosion of transobturator tape for stress urinary incontinence. Int. Urogynecol. J. Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007, 18, 207–212.

- Ford, A.A.; Rogerson, L.; Cody, J.D.; Aluko, P.; Ogah, J.A. Mid-urethral sling operations for stress urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 7, Cd006375.

- Lee, D.; Zimmern, P.E. Management of complications of mesh surgery. Curr. Opin. Urol. 2015, 25, 284–291.

- Committee on Gynecologic Practice American Urogynecologic Society. Committee Opinion No. 694: Management of Mesh and Graft Complications in Gynecologic Surgery. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 129, e102–e108.

- Haylen, B.T.; Freeman, R.M.; Swift, S.E.; Cosson, M.; Davila, G.W.; Deprest, J.; Dwyer, P.L.; Fatton, B.; Kocjancic, E.; Lee, J.; et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint terminology and classification of the complications related directly to the insertion of prostheses (meshes, implants, tapes) and grafts in female pelvic floor surgery. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2011, 30, 2–12.

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!