Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

As is widely known, the COVID-19 pandemic has affected tourism and related activities globally. Due to the restrictive measures implemented for gatherings and movements in order to limit the spread of the virus, conferences and conference tourism received a strong shock since the majority of them were canceled or postponed.

- conference tourism

- COVID-19

- digital and hybrid conferences

1. Introduction

The outbreak of COVID-19 caused a sense of fear among the global population, disrupting daily life and impacting the global economy. Direct impacts were also observed in the healthcare sector, which were identified as unprecedented and, above all, unforeseen. As expected, the pandemic crisis affected all sectors of the economy, naturally including tourism [1]. However, it also became a catalyst for the introduction of innovative technologies in everyday life in order to meet new needs [2].

Conference tourism falls under business tourism, which is an alternative form of tourism that has seen considerable growth in recent years [3]. Besides its dynamic and growth prospects, it also contributes to the national economy and the mitigation of tourism seasonality [4][5]. The impacts of this pandemic became clear early on due to the ban on assembly. However, the conference planning industry responded relatively promptly and attempted to make use of new technologies in order to adapt to the situation [6]. Therefore, the new circumstances resulting from COVID-19 restrictions led to the digital transformation of global conference tourism, while many researchers began wondering if this situation was transitional or permanent [7].

2. COVID-19 and Tourism

As per Blake and Sinclair’s research [8], crises are nothing new in tourism. However, the impact of this pandemic, mainly in financial terms, has so far been the most devastating compared to other similar crises in modernity, as traveling has been substantially reduced [9][10]. In the beginning, everyone’s attention turned to protection and resilience, while later on questions were raised as to the ways the tourism industry can respond and rebound [11]. Solving this issue is a significant challenge for stakeholders and the scientific community, whereas technology is a factor of particular relevance in this process [12].

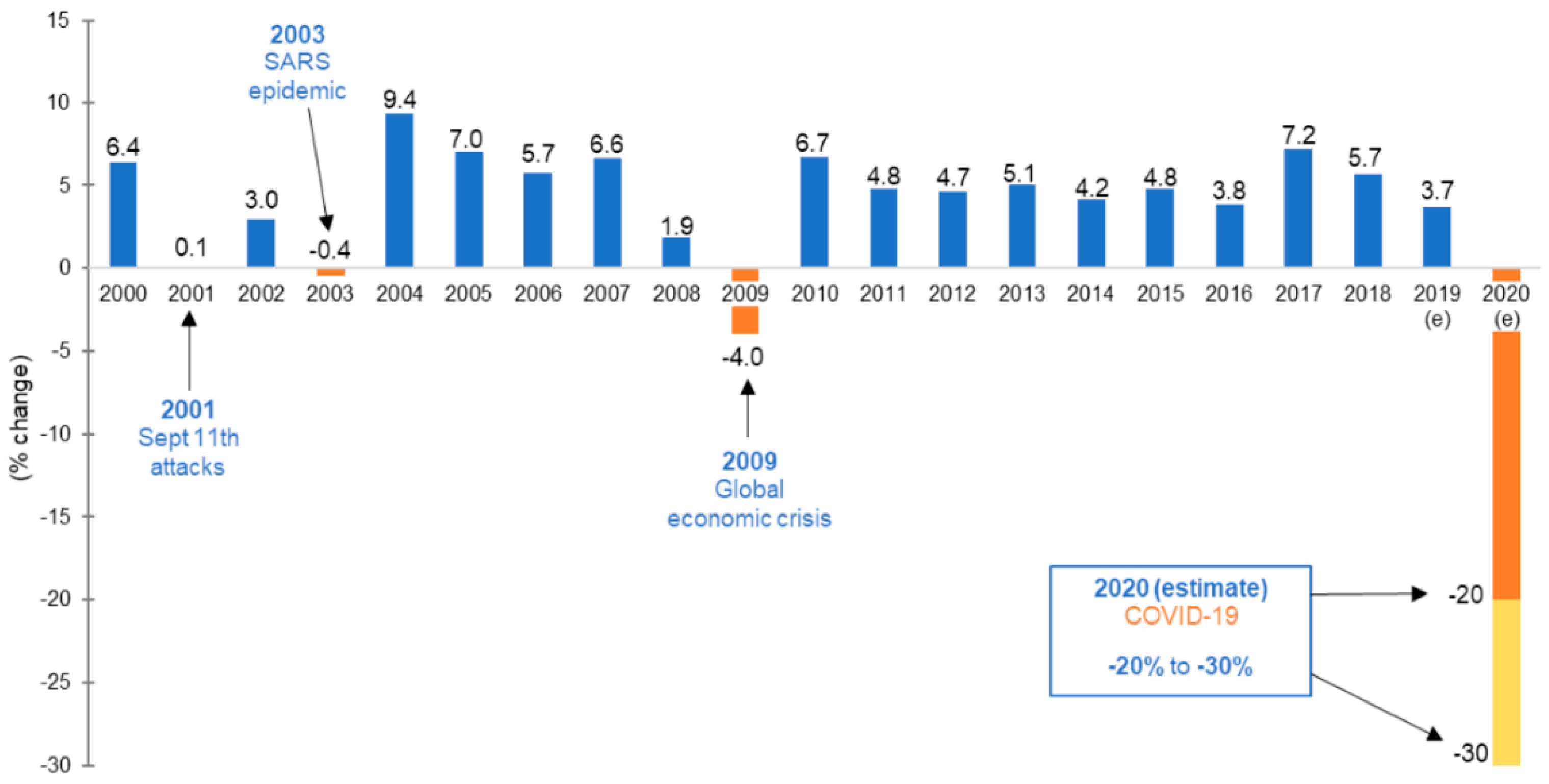

According to UNWTO [13], in 2020, when COVID-19 began spreading, international arrivals saw a decline of 65% in the first quarter of 2020 due to extended lockdowns and travel restrictions, which translated to USD 460 billion and a 50% decrease in tourism expenditure throughout the year. Figure 1 indicates the percentage change in international arrivals due to COVID-19 and other external factors from 2000 to 2010. These factors are the terrorist attack of 9/11 (2001), the SARS pandemic outbreak (2003), the impact of the global recession (2009) and the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak (2020). Clearly, the COVID-19 outbreak was what led to the most significant decrease in international arrivals for this period. Based on the point of view of Figini and Patuelli [14], in 2020, international tourist destinations (e.g., France, Spain and Italy) suffered more significant GDP losses, unlike countries less dependent on tourism (e.g., Sweden, Germany).

Figure 1. Impact of COVID-19 and other external phenomena on international tourist arrivals. Source: UNWTO [15].

3. COVID-19 and Conferences

Through a literature review of COVID-19 and tourism publications, it seems that the existing literature is divided into two categories. The first includes research focusing on the negative impact of the pandemic on local economies, the image of certain destinations and the mental health of tourists. The second category focuses on the pandemic as an opportunity to reconsider and improve the way the tourism industry works [16]. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on conference and business tourism in general has only been studied by a few researchers to date. One of the measures enforced by governments around the world to restrict the virus spread was the closing of borders to non-residents and non-citizens [10][17][18]. Indeed, 2020 was the year that saw the way conferences are carried out change and signaled their adaptation process in the face of the pandemic, which proved to have a significant impact on the sector on a global scale, resulting in a considerable shift in the previously held perceptions of it. Since March 2020, companies had to restrict employee commutes due to the outbreak of the pandemic [19]. Bans on international travel and the uncertainty revolving around documentation policies were the principal obstacles facing professional travelers globally [6][20].

The COVID-19 pandemic has, regrettably, brought the MICE sector to a complete halt and caused the biggest interruption to the world economy since World War II [21]. However, new ways of carrying out conferences emerged, along with the alternatives implemented by the organizers. Specifically, hybrid and virtual meetings were introduced in order to reduce postponement and cancelation rates. Hybrid and virtual meetings helped organizing bodies as well as unions retain their members’ devotion and even expand in new markets [22]. A total of 8409 meetings were carried out or organized for 2020. Compared to the previous year, this number is lagging behind, as in 2019, conferences reached 13.252 [23]. Therefore, conference organizers had to adjust to the new reality in order to meet the challenges since live conferences were banned [24].

The improvement of existing digital platforms and the development of new systems for sharing scientific knowledge have enabled the scientific community to “meet” again via novel virtual environments (e.g., Teams, Zoom, Skype, Cisco WebEx, Google Hangouts, etc.), providing an opportunity to reform methods of organizing academic conferences in all disciplines. On the one hand, virtual events have a much lower environmental and economic impact than regular meetings. Organizers, on the other hand, could expand the number of opportunities for researchers, particularly those in the early phases of their careers, to present their work and to attend high-quality seminars. Online conferences are boosting the diversity of speakers and allowing researchers to participate at much higher levels [25]. Finally, attending virtual conferences spares participants from exhausting long-distance travel and saves a significant amount of money on commuting expenses while lowering the likelihood of contracting the infectious virus [26].

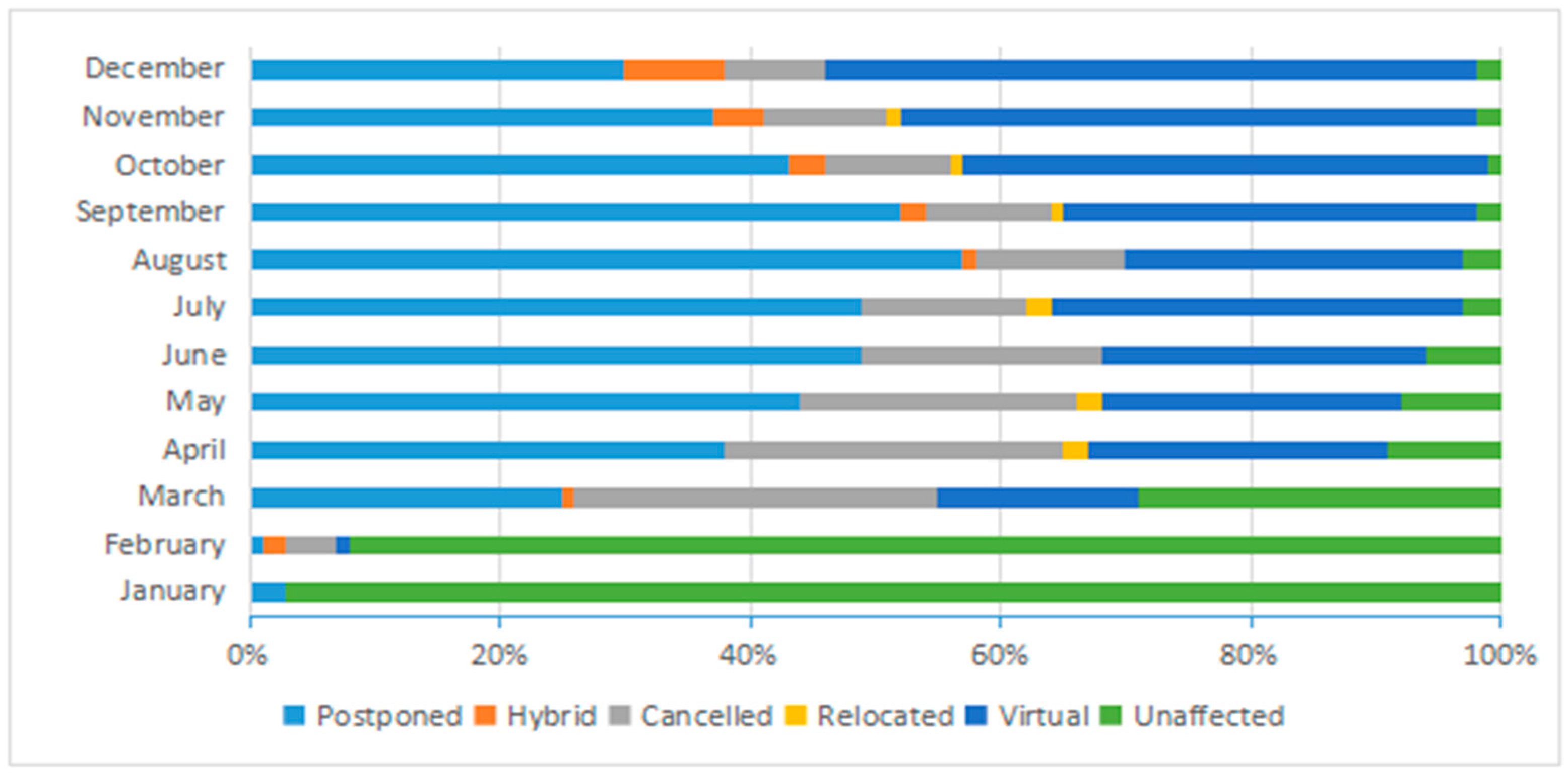

According to Figure 2, since March, when COVID-19 started to spread, a very small percentage of conferences remained unaffected and were carried out normally. In the first few months that the virus spread, most conferences were canceled (44%). This trend picked up speed around the middle of the year and gradually reduced in the second quarter when new ways of carrying them out emerged. The second largest percentage is that of virtual meetings (30%), which started at a relatively small percentage and grew until they surpassed the percentage of postponed conferences in the last couple of months of the same year.

Figure 2. COVID-19 impact on conferences per month rate. Source: UNWTO [14].

The canceled conferences hold the third place (14%), and while they represented the largest segment during the outbreak of the pandemic, at the end of the year, they ranked next to last, which reveals the extent to which conferences adjusted to the new reality. Hybrid conferences, which the participants can attend online or in person, became more popular by August since they represented an innovative endeavor that gained momentum in 2021. Finally, the conferences that were rescheduled were the less favorable choice throughout the year, reaching just 1%.

In 2019, 13,252 conferences were held, and the estimated expenditure reached $10,817 million. In 2020, 8409 conferences were planned, of which 3484 were held (763 unconferences, 2505 digital, 143 hybrid and 73 transferred) [23]. As expected, the COVID-19 pandemic brought about changes compared to the previous year, which also affected the economy. Table 1 illustrates how the economic contribution of conferences can be justified for 2020.

Table 1. Potential financial contribution of conferences for 2020.

| Total Estimated Expenditure 2019 | 13,252 Conferences |

| Loss due to COVID-19 | 4843 fewer conferences compared to the previous year |

| Loss due to canceled conferences | 1211 out of the 8409 planned conferences were canceled |

| Loss due to canceled conferences | 3714 out of 8409 planned conferences postponed until 2021 or later |

| Damage through digital/hybrid conferences | Digital and hybrid conferences have a smaller financial contribution compared to face-to-face conferences. In addition, the registration and participation fee is usually lower |

| Estimated total expenditure 2020 | Unaffected and transferred conferences: 836 Number of participants in the unaffected and transferred conferences: 418 Average registration cost for unaffected and transferred conferences: $571 Estimated total cost of unaffected and transferred conferences: $907 M Digital/hybrid conferences: 2.648 Average registration cost for digital/hybrid conferences: $211 Estimated total cost of digital/hybrid conferences: $758 |

Source: ICCA [23], the authors’ elaboration.

Taking 2019 as a baseline, the table illustrates the decrease in estimated total conference expenditures due to the emergence and spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. This decrease was mainly due to the lower number of scheduled conferences, a reduction in spending due to canceled and postponed conferences and the increase in digital and hybrid conferences leading to lower costs for attendees (lower registration fee and not requiring transportation and accommodation). Although the transition to virtual conferences was difficult due to the pandemic, attendees report significant differences between virtual and physical meetings. Some participants claim that they do not experience the same sense of community at virtual conferences; thus, they long for in-person meetings. Virtual conferences, on the other hand, limit the chances for attendees to share personal experiences with one another, which is one of the main advantages of on-site conferences [27].

4. Conference Tourism

According to UNWTO [28], people traveling for business purposes are considered tourists. Business tourism combines leisure with work and includes four subcategories. Conference tourism is one of the subcategories along with exhibition tourism, incentive travel and individual business travel [29]. This has to do with a type of travel that can be defined as people who go to business meetings and events at a common destination [30]. The profile of this category of tourists usually concerns economically strong people with a high level of education [31]. Conferences are meetings that do not require periodicity for their convergence. Although there is no time limit, most of them last 3 days in order to exchange opinions, engage in knowledge transfer and publicize specific issues. The main activities of the participants concern attending parallel educational lectures or events and participating in meetings and discussions [32].

Conference tourism concerns a large percentage of the market while contributing to tourism development and increasing tourist flows. There has been an important increase in the number of meetings, particularly international ones, which were formerly uncommon. Beyond the income from the primary activity, it also produces several benefits in additional fields. In addition, it can prolong the tourism season because of its year-round, season-neutral nature, which allows for year-round planning. Encouraging the growth of the city’s or region’s infrastructure is another significant consequence. At the same time, MICE tourism-hosting countries and regions receive far quicker and more efficient promotion. Due to these economic activities, international conference tourism is becoming one of the most popular kinds of travel in several countries [33].

Cities and regions can grow their conference tourism industry if the supporting attractions and environmental factors permit. Congress centers and halls, large hotels and other lodging alternatives, infrastructure, conditions, and transportation options, as well as climate and geographic position, are all crucial for the growth of conference tourism [34].

Organizations and associations are actively working to promote conference tourism on a global scale. Their contribution to the industry’s growth is especially significant regarding the operational and management part of the conferences and the transmission of know-how. The International Association of Professional Congress Organizers (IAPCO) and the International Congress and Convention Association (ICCA) meet on an international basis, while the European Federation of the Associations of Professional Congress Organizers (EFAPCO) meets on a European level. The contribution of the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) is also noteworthy as it has contributed to its development and evolution.

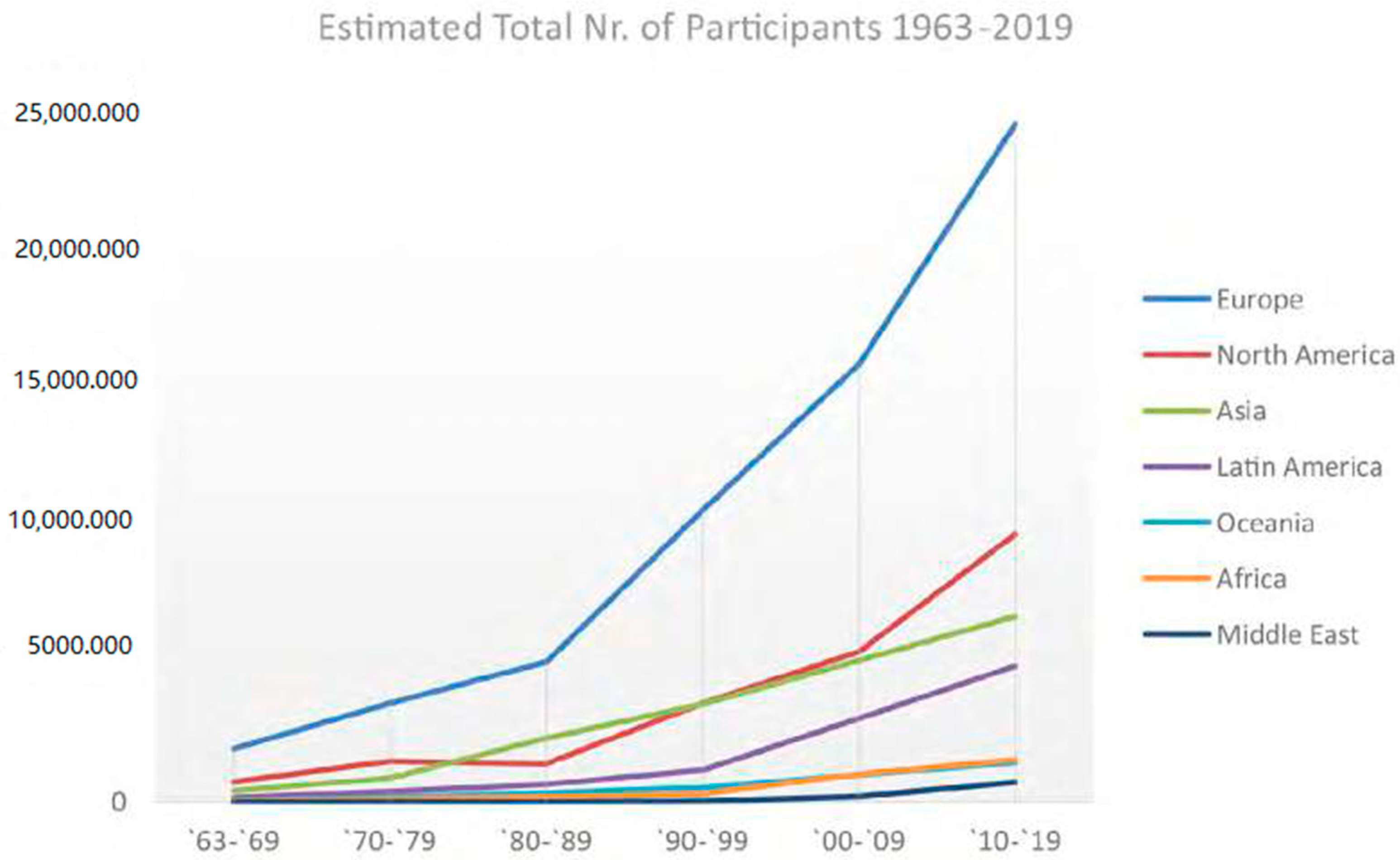

According to Figure 3, Europe has a higher market share of conferences and participants than the rest of the globe. Numerous European capitals and centers have been granted the chance to organize conferences because of their advantageous geographic location. It was the host of 53% of all meetings that were scheduled in 2019. North America and Asia followed, with the latter registering a notable increase [35].

Figure 3. Estimated total number of participants (1963–2019). Source: ICCA [35].

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/businesses3040037

References

- Duro, J.A.; Perez-Laborda, A.; Turrion-Prats, J.; Fernandez, M. COVID-19 and tourism vulnerability. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2021, 38, 100819.

- Atluntas, F.; Gok, M.S. The effect of COVID-19 pandemic on domestic tourism: A DEMATEL method analysis on quarantine decisions. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102719.

- Kokkosis, C.; Tsartas, P.; Griba, E. Special and Alternative Forms of Tourism. In Demand and Supply of New Tourism Products; Kritiki: Athens, Greece, 2011; (Ιn Greek).

- Marques, J.; Santos, N. Developing Business Tourism beyond Major Urban Centers: The Perspectives of Local Stakeholders. Tour. Hosp. 2016, 22, 1–15.

- Malik, G. NICHE Tourism: A Solution to Seasonality. J. Manag. Res. Anal. 2018, 5, 80–83.

- Houston, S. Lessons of COVID-19: Virtual conferences. J. Exp. Med. 2020, 217, e20201467.

- Salomon, D.; Feldman, M.F. The future of conferences today. Are virtual conferences a viable supplement to “live” conferences? EMBO Rep. 2020, 21, e50883.

- Blake, A.; Sinclair, M.T. Tourism crisis management: US response to September 11. Ann. Tour. Res. 2003, 30, 813–832.

- Hall, C.M.; Scott, D.; Gossling, S. Pandemics, transformations and tourism: Be careful what you wish for. Tour. Geogr. 2020, 22, 577–598.

- Sigala, M. Tourism and COVID-19: Impacts and implications for advancing and resetting industry and research. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 312–321.

- Prayag, G. Time for reset? Covid-19 and tourism resilience. Tour. Rev. Int. 2020, 24, 179–184.

- Gossling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 29, 1–20.

- UNWTO. World Tourism Barometer; UNWTO eLibrary: Madrid, Spain, 2020; Volume 18, pp. 1–24.

- UNWTO. 2020. Available online: https://webunwto.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/2020-03/24-03Coronavirus.pdf (accessed on 2 March 2023).

- Figini, P.; Patolli, R. Estimating the economic impact of tourism in the European Union: Review and computation. J. Travel Res. 2022, 61, 1409–1423.

- Seraphin, H. COVID-19: An opportunity to review existing grounded theories in event studies. J. Conv. Event Tour. 2021, 22, 3–35.

- Bakar, N.A.; Rosbi, S. Effect of Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) to tourism industry. Int. J. Adv. Eng. Res. Sci. 2020, 7, 189–193.

- Jones, P.; Comfort, D. The COVID-19 Crisis, Tourism and Sustainable Development. AJT 2020, 7, 75–86.

- Valenti, A.; Fortuna, G.; Barillari, C.; Cannone, E.; Boccuni, V.; Iavicoli, S. The future of scientific conferences in the era of the COVID-19 pandemic: Critical analysis and future perspectives. Ind. Health 2021, 59, 334–339.

- Gottileb, M.; Landry, A.; Egan, D.J.; Shappell, E.; Bailitz, J.; Horowitz, R.; Fix, M. Rethinking Residency Conferences in the Era of COVID-19. AEM Educ. Train. 2020, 4, 313–317.

- Baum, T.; Nguyen, H. Hospitality, tourism, human rights and the impact of Covid-19. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2397–2407.

- Menegaki, A.N. Hedging Feasibility Perspectives against the COVID-19 for the International Tourism Sector. Preprints 2020. not peer reviewed.

- ICCA. ICCA Annual Statistics Study 2020. Analyzing an Exceptional and Transformational Year. 2020. Available online: https://www.pot.gov.pl/attachments/article/8932/ICCA%20Statistics%20Study%202020.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2022).

- Rundle, C.W.; Husayn, S.S.; Dellavalle, R.P. Orchestrating a virtual conference amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Dermatol. Online J. 2020, 26, 16–19.

- Bottanelli, F.; Cadot, B.; Campelo, F.; Curran, S.; Davidson, P.M.; Dey, G.; Raote, I.; Straube, A.; Swaffer, M.P. Science during lockdown—From virtual seminars to sustainable online communities. J. Cell Sci. 2020, 133, jcs249607.

- Cai, Q.; Du, Z.; Wu, Y.; Xu, X. Rethinking Academic Conferences in the Age f Pandemic. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8351.

- Donlon, E. Lost and found: The academic conference in pandemic and post-pandemic times. Ir. Educ. Stud. 2021, 40, 367–373.

- UNWTO. Global Report on the Meetings Industry. AM Rep. 2014, 7, 4–64.

- Wooton, G.; Stevens, T. Business tourism: A study of the market for hotel-based meetings and its contribution to Wale’s tourism. Tour. Manag. 1995, 16, 305–313.

- Ahmed, S. The Exploration of New Avenues toward Better Business Management: A Business Tourism Perspective; IGI Publisher: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020.

- Pechlaner, H.; Zeni, A.; Raich, F. Congress Tourism and leisure tendencies with special focus on economic aspects. Tour. Rev. 2007, 62, 32–38.

- Nicula, V.; Elena, P.R. Business Tourism Market Developments. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 16, 703–712.

- Timor, A.N. International Congress Tourism: Overview in the World and Turkey. Nat. Sci. 2011, 6, 124–144.

- Rustamovich, S.Z. The importance of congress tourism in the development of economic integration. Zien J. Soc. Sci. Humanist. 2022, 14, 167–168.

- ICCA. ICCA Statistics Report Country & City Rankings—Public Abstract. The International Association Meetings Market 2019. 2019. Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/525577060/ICCA-Statistics-2019-final (accessed on 18 September 2022).

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!