2. The Relationship between NPDC and Lysosomes

2.1. Lysosomal Appearance and the Changes in Lysosomes in NPDC

Lysosomes are complicated intracellular organelles regulated by luminal pH, cellular nutrients, protein homeostasis, the transportation of ions, and pathogenic infections [

47,

49,

50,

51]. NPDC and cholesterol accumulation induce imbalances in cellular functions. To maintain the function of lysosomal membrane proteins, lysosomes must exist in intact forms to not cause membrane destabilization.

NPC1 knock-out disrupted lysosomal morphology in a mice model, and increased lysosomal-associated membrane protein (LAMP)-1 was observed in NPDC mice and NPDC patients [

52,

53,

54]. LAMP-1 is expressed in the lysosomal membrane to modulate lysosomal activity. Deficiencies in

NPC1 not only increased LAMP-1 expression but also LAMP-1 glycosylation [

55]. Glycosylation is an essential process for lysosomal membrane proteins for vesicle trafficking, and the abnormal glycosylation of LAMP-1 possesses the potential to induce NPDC [

56]. LAMP-1 hyper-glycosylation was observed in the cerebellum of

NPC1 knock-out mice [

55]. In addition, lysosomal membrane stabilization is associated with ion transportation through the lysosomal membranes. The transportation of Ca

2+ has been fully studied for lysosomal activation [

57]. Glycyl-L-phenylalanine 2-naphthylamide (GPN, lysosomotropic agent, a drug that penetrates lysosomes)-induced lysosomal Ca

2+ release was attenuated in an NPDC-mimicking cellular model using U18666a with a megakaryocyte cell line (MEG-01), as well as in bacterial-infected RAW 264.7 cells, which inhibited the expression of NPC1 [

52,

58]. Regardless of the lysosomal components, the activation of lysosomes is regulated by lysosomal positioning [

59]. Lysosomal movement plays a role in degrading substrates by fusing with autophagosomes and delivering cargos such as cholesterol. However, cholesterol accumulation in NPDC blocks lysosomal positioning [

60]. In lysosomal transportation of cholesterol to the ER, the phosphorylation of phosphatidylinositol (PI) through phosphatidylinositol 4 kinases (PI4Ks) is induced to synthesize phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PtdIns4P), which is located on the lysosomal membrane [

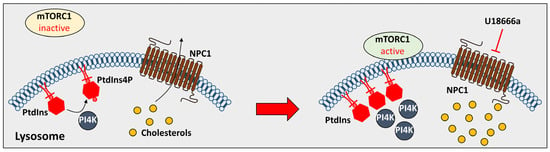

61]. The inhibition of NPC1 through U18666a recruited PtdIns4P and PI4K and accumulated PtdIns4P and PI4K in the lysosomal membrane to inhibit autophagy by activating rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1), as described in

Figure 2 [

61]. Consequently, deficiency in NPC proteins modulates lysosomal proteins and positioning and subsequently blocks lysosomal cholesterol trafficking.

Figure 2. The effect of U18666a on PtdIns4P. The treatment of U18666a inhibits phosphorylation of PtdIns and induces activation of mTORC1 to inhibit cholesterol transport. NPC1: Niemann-Pick type C 1; PtdIns4P: phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate; and PI4K: phosphatidylinositol 4 kinases.

2.2. The Effect of the Lysosomal Proteins on NPDC

Lysosomal membrane proteins have connections with ER membrane proteins to transfer cholesterol from lysosomes to the ER. The ER is associated with lysosomal membrane proteins, such as star-related lipid transfer domain-containing 3 (StARD3), ras-related protein rab-7, and oxysterol-binding protein homologue express [

81]. In

NPC1 mutant Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, endolysosomal protein annexin A6 blocks ER-endolysosome connection by inhibiting StARD3 and rab-7 [

82]. The knock-down of

annexin A6 in

NPC1 mutant CHO cells recovers cholesterol trafficking endolysosomes to ER [

82]. In addition, the motor protein of lysosomes affects cholesterol transportation. For example, the biogenesis of lysosome-related organelle (BOLC) one-related complex (BORC) recruits ARL8 to bind the kinesin light chain/kinesin family member 5 complex, which binds microtubules to move lysosomes [

83]. The knock-out of

BORC and

ARL8 caused cholesterol accumulation, which is indicated by an increase in the filipin intensity in HeLa cell lysosomes [

74]. Disruption of the BORC/ARL8 complex induced the secretion of NPC2 from lysosomes [

74]. Lysosomes have components that are physically involved in the transportation of cholesterol. The lysosomal proteins not only directly contact proteins but are involved in cholesterol transportation and NPDC-related reactions. Nutrient starvation is the classical stimulation of macroautophagy, which induces lysosomal activation by decreasing amino acid levels in lysosomes [

84]. This starvation inhibits mammalian targets of mTORC1, which inhibits lysosomal binding to lysosomes [

85]. mTORC1 inhibition induced nuclear translocation of the transcription factor EB (TFEB) to express lysosomal genes to activate lysosomes [

85]. The knock-out of

NPC1 induced mitochondrial damage and lysosomal membrane damage with the hyper-activation of mTORC1 in mouse embryonic fibroblasts [

75]. The deletion of

NPC1 disrupted mitochondria morphology and increased LAMP2 accumulation [

75]. The inhibition of mTORC1 through the Torin1 mTORC1 inhibitor recovered mitochondrial function and lysosomal membranes [

75]. The TFEB activator genistein stimulated nuclear translocation and autophagic flux to increase LC3 II expression in NPDC patient fibroblasts [

76]. Treatment with genistein induced lysosomal exocytosis and decreased cytosolic cholesterol levels in NPC1 patient fibroblasts [

76]. Additionally, the lysosomal Ca

2+ channel two-pore channel 2 (TPC2) regulates cholesterol accumulation [

77]. An agonist of TPC2 (TPC2-A1-P) decreased cholesterol levels with the exocytosis of lysosomes in the human fibroblasts of NPDC patients [

77]. The treatment of TPC2-A1-P attenuated the intensity of filipin, the cholesterol-detecting dye, and the fusion of LAMP1 with the plasma membrane [

77]. Thus, regulation of the lysosomal proteins has been suggested as a therapeutic strategy for NPDC. However, the activation of lysosomes against NPDC does not always reflect satisfied results. For example, treatment with Torin1, which recovers lysosomal membranes as described above, failed to decrease cholesterol accumulation in lysosomes [

75].

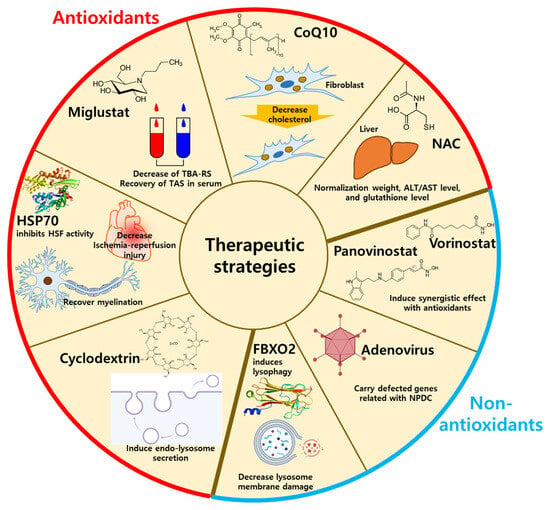

3. Current Therapeutic Strategies for NPDC

Various approaches to treating NPDC have been studied, such as simply lowering cholesterol, alternatively using other LSD drugs, and manipulating NPDC-related genes [

29]. Additionally, adeno-associated viral vectors, heat shock protein (HSP), synthetic high-density lipoprotein (sHDL), histone deacetylase inhibitors, and F-Bod protein2 (Fbxo2)-mediated lysophagy have been suggested as NPDC therapies [

91,

92,

93,

94,

95]. Especially, sHDL showed high efficiency in reducing cholesterol with cellular safety in

NPC1I1061T-mutated human fibroblasts [

92]. Mechanistically, sHDL modulates cholesterol regulatory genes, including

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase,

hydroxymethylglutary-CoA synthase,

ATP binding cassette subfamily A1, and

NPC1 [

92]. Although numerous drugs have been introduced, antioxidant-related drugs and strategies have also been suggested for NPDC treatment. Thus, the researchers summarized the antioxidant-related drugs and non-antioxidant methods for NPDC treatment (

Figure 3).

Figure 3. The therapeutic strategies using antioxidants or non-antioxidants. The antioxidants-related NPDC treatment includes HSP70, miglustat, CoQ10, cyclodextrin, and NAC by decreasing oxidative stresses. The non-antioxidant-related NPDC treatment includes lysophagy, panovinostat, vorinostat, and adenovirus by supplementation of antioxidants. HSP70: heat shock protein 70; CoQ10: coenzyme Q10, NAC: N-acetylcysteine; FBXO2: F-Box protein 2.

3.1. Antioxidant-Related Drugs for NPDC Treatment

3.1.1. N-Butyl-Deoxynojirimycin (Miglustat)

As mentioned in the Introduction, oxidative stress is an outcome of NPDC. For example, thiobarbituric acid-reactive species (TBARS), the product of lipid peroxidation, was found to be increased, and the total antioxidant status (TAS) was decreased in the plasma of NPC patients [

96]. Although the damaging effects of miglustat, the inhibitor of glycosphingolipid synthesis, on the neuronal system in NPDC patients have not been demonstrated, treatment with miglustat attenuated TBARS levels and recovered TAS levels in the serum of patients with NPDC [

96].

3.1.2. N-Acetylcysteine and Coenzyme Q10

Antioxidants and antioxidation-related compounds, including

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10), have therapeutic effects on NPDC [

97]. The ROS scavenger NAC has been suggested as a clinical application to manage oxidative stress [

98]. Treatment with NAC recovered liver pathology in NPDC mice [

99]. NAC normalized liver weight, plasma levels of alanine aminotransferase (ALT)/aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and liver glutathione levels in NPDC mice [

99]. CoQ10 is a component of the electron transport chain and acts as a lipophilic antioxidant [

100]. Treatment with CoQ10 decreased cholesterol levels in NPDC patient dermal fibroblasts and cytokine levels in NPDC patient fibroblast-culture media [

101].

3.1.3. Heat Shock Factor

Heat shock factors (HSFs) are metabolic proteins that induce protein folding, inhibit protein misfolding and aggregation, and prevent apoptosis [

102,

103] and oxidative stress [

104]. For instance, heat shock protein 70 (HSP70) inhibited the activity of HSF, which induced the antioxidant reaction and reduced oxidative stress and ischemia/reperfusion injury [

104,

105]. HSP70 also recovered myelination in

NPC knock-out mice [

91,

106]. In NPDC, myelin expression is defective because cholesterol is a component of myelination [

107]. Thus, myelin defects are considered a marker of NPDC, and HSP70 is suggested for NPDC therapy.

3.1.4. Cyclodextrin

The β-cyclodextrin (CD) is the drug most frequently used for NPDC to decrease lysosomal cholesterol levels [

108,

109]. β-CD has been suggested as a secondary antioxidant, which enhances traditional antioxidants, such as resveratrol, pterostilbene, pinosylvin, oxyresveratrol, and astaxanthin [

110], and β-CD shows antioxidant activity, although its efficacy is lower than that of traditional antioxidants [

111]. Although the specific mechanisms of β-CD on lysosomes have not been demonstrated, derivatives of β-CD, such as 2-hydroxypropyl-β-CD (HP-β-CD) and 6-O-α-maltosyl-β-CD (Mal-β-CD), modulate lysosomes. HP-β-CD decreased lysosomal accumulation with decreases in lysosomal sphingolipid in

NPC1-deleted CHO cells [

112]. In HeLa cells, HP-β-CD induced endolysosomal secretion by activating transient receptor potential mucoplin-1 Ca

2+ channels to reduce accumulated cholesterol [

113]. Treatment with HP-β-CD induces lysosome-ER connections to trigger cholesterol trafficking [

114]. In the same way, Mal-β-CD decreased the accumulation of lysosomes by reducing lysosomal expansion in

NPC1-deficient CHO cells [

115,

116].

3.2. Non-Antioxidant Methods for NPDC Treatment

3.2.1. Lysophagy

Lysosomal membrane impairment induces oxidative stress [

117,

118]. Deletion of the

Fbxo2 gene decreased lysophagy in mouse cortical neurons [

94]. Fbxo2 treatment for NPDC decreased lipid-mediated lysosomal membrane damage [

94]. These results suggest that oxidative stress is associated with cholesterol trafficking, and thus, lysophagy might help reduce cholesterol accumulation. Although non-antioxidant mechanisms are not the same as those of antioxidants, non-antioxidants effectively assist antioxidant-related drugs through synergistic effects with the development of endosomal and lysosomal trafficking.

3.2.2. Histone Deacetylase Inhibitors

The histone deacetylase inhibitors vorinostat and panobinostat recovered mutated

NPC1I1061T localization [

119].

NPC1I1061T mutation separated NPC1 from lysosomes, and treatment with vorinostat and panobinostat induced the movement of the

NPC1 I1061T mutant type to lysosomes [

119]. Although vorinostat and panobinostat are not antioxidants, the combination of these and antioxidants, such as vitamin C and naringenin, showed synergistic effects with vorinostat and panobinostat [

120,

121]. Antioxidant-related molecules, including β-CD, vorinostat, and panobinostat, have therapeutic potential for NPDC, but the relationship between these molecules and oxidation has not been fully demonstrated. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved another histone deacetylase, valproic acid (VPA), to reduce cholesterol accumulation in NPDC patient-derived fibroblasts [

93]. The combined administration of VPA with another CD-type of M-β-CD induced NPC1 trafficking from endosomes to the ER or Golgi in

NPC1I1061T-mutated human fibroblasts [

93], providing evidence of the synergistic effect with antioxidants of lysosomal trafficking.

3.2.3. Adenovirus

Adenovirus has been used as a gene delivery vector to easily penetrate cellular membranes and transfer to the nucleus [

122,

123]. The transduction of adenovirus cloning with

NPC1 genes induced the stable expression of NPC1 proteins in

NPC1 knock-out mice [

124]. Injection with

NPC1-inserted adenovirus increased the survival rate of Purkinje cells in

NPC1 knock-out mice [

125]. Recovery of Purkinje cells by adenovirus injection ameliorated impaired behavior and the survival rates of

NPC1 knock-out mice [

125]. Adenovirus early region 3 (RIDα) mimics the role of rab7 protein in the translocation of endosomes and lysosomes [

126,

127]. Rab7 interacts with lysosomal motor dynein and OSBP family ORP1L, which senses cholesterol levels in lysosomes for the translocation of lysosomes [

128,

129]. RIDα is substituted for rab7 in rab7-depleted cells to translocate cholesterol [

126,

127]. RIDα also induced the repositioning of lysosomal and autophagic vesicles to juxtanuclear regions to trigger autophagic flux and cholesterol trafficking in NPDC fibroblasts [

130].