Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is an old version of this entry, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Subjects:

Nutrition & Dietetics

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a growing global health problem. Evidence suggests that diets rich in phytochemical-containing herbs and spices can contribute to reducing the risk of chronic diseases.

- diabetes

- herbs and spices

- metabolic syndrome

- nutrition

- phytochemicals

- preventative health

1. Introduction

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) and its associated conditions, such as obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular disease, are a growing global health problem. Between 2000 and 2019, global diabetes rates grew by more than 1.5% annually and prevalence rates for all other metabolic diseases also increased [1]. Poor diet and physical inactivity are risk factors for the development of MetS and lifestyle changes are key for treatment [2]. MetS involves the dysregulation of blood glucose, insulin resistance, raised blood lipids, increased inflammation and high blood pressure [2]. Therefore, measuring these biomarkers in healthy individuals can indicate the risk of MetS developing or can be used to monitor progress in those with MetS.

Research indicates that the inclusion of herbs and spices in the diet, as is often the case in Mediterranean and Asian diets, may contribute to positive long-term health outcomes [3,4]. Herbs and spices are a particularly rich source of phytochemicals and the consumption of diets rich in phytochemicals has been linked with a reduced risk of cardiometabolic disease and obesity [5,6].

Many studies looking at the health benefits of herbs and spices use high-dose extracts; however, these do not reflect the main way that the general public might be able to take advantage of these relatively cheap additions to their diet. Are these more expensive high-dose formulations necessary for everyone to benefit from herbs and spices, or do culinary doses provide benefits too?

Some researchers have begun to investigate this question. Clinical studies using herb and spice mixes to improve physiological responses to food have indicated that the inclusion of herbs/spices in the diet may have preventative or therapeutic benefits [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. The spice mixes used in these studies ranged in dose from 6 g to 23.5 g and positively impacted vascular function, blood glucose and insulin and blood lipids following meals. These effects may contribute to a reduced risk of MetS and its associated conditions when herbs and spices are consumed regularly. The reasons for the specific herb/spice mixes chosen and doses used were often not explained. Doses of 6 g of Italian herb mixes [8], 23.5 g of Asian spices [11] or a combination of Mediterranean herbs and Asian spices at doses of 14.5 g [10] and between 0.5 and 6.6 g [13,14] have been found to have benefits. The lack of consistency in herb/spice mix formulations makes it challenging to attribute benefits to a particular herb/spice, a combination of herb/spices or a dose.

Zanzer et al. assessed the effect of the concentrated liquid extracts of individual spices, but standardized them to equal polyphenol contents, enabling the different effects from each spice to be elucidated [15]. The dose of polyphenols provided from each extract corresponded to the amount found in 6 g of cinnamon. Cinnamon and turmeric positively impacted on blood sugar levels, and turmeric reduced appetite; however, ginger and star anise did not have any effect. Therefore, the individual effects from different herbs goes beyond a general benefit from polyphenol intake and needs to be clarified.

2. Black Pepper, Cardamom and Chilli

There was one single-blind cross-over trial on black pepper in healthy adults. A dose of 1.3 g added to a meal had no impact on appetite or thermogenesis [138].

Ten studies (eight double-blind RCTs, one single-blind RCT and one clinical study) looked at the impact of cardamom on inflammation and a range of metabolic markers in individuals with hypertension [27], diabetes [29,32,59], prediabetes [28], poly-cystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) [34,35] and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [30,33]. All the studies on cardamom used 3 g/day for between 8 and 20 weeks. Five out of six studies that investigated inflammatory markers found positive effects [28,30,31,32,34,35], two studies found benefits on blood glucose and insulin and two studies found no benefit from cardamom on blood lipids, while effects on blood pressure were variable.

Eleven clinical studies [9,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45] investigated the effects of chilli on appetite, vascular function and blood glucose, insulin and lipids. Apart from one study looking at the effect of chilli on glucose and insulin in pregnant women with gestational diabetes [42], all the included studies were in healthy individuals.

Four of the intervention studies used doses of 30 g of fresh chilli [36,37,38,39], the other seven intervention studies used doses of 0.6 g [40], 1.25 g [42], 3.09 g [44,45] or 5 g [43], a meal with chilli containing 5.82 mg of capsaicinoids [9] or chilli capsules containing 10 mg of capsaicinoids [41].

Appetite and/or thermogenesis or metabolic rate were measured in eight out of thirteen of the studies and five of these found a beneficial effect. There were as many studies finding positive results as those showing no effect for the key metabolic biomarkers of blood glucose, insulin and lipids (see Figure 2).

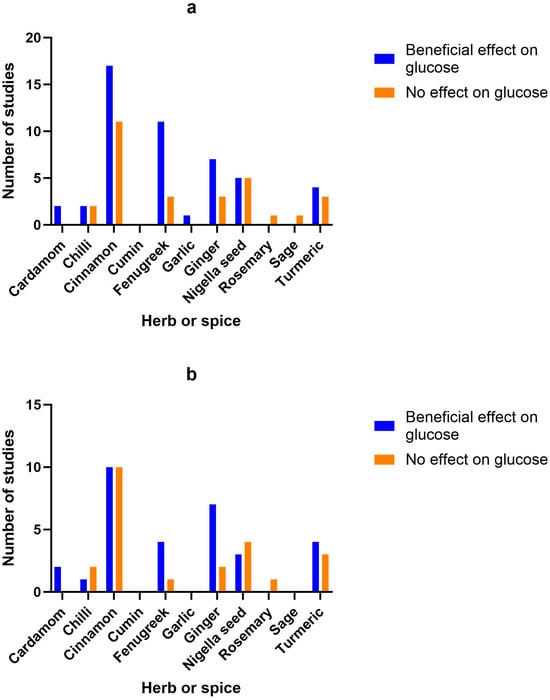

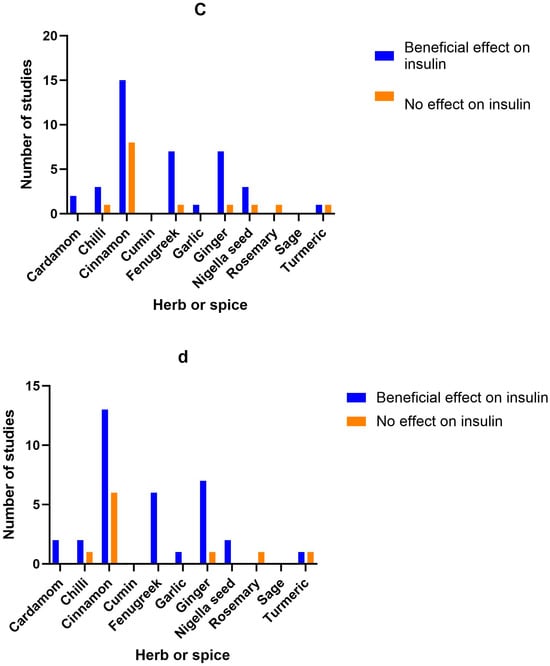

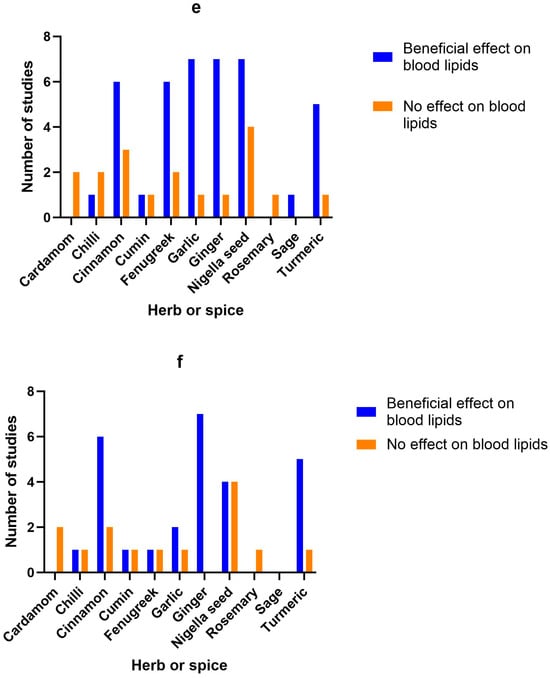

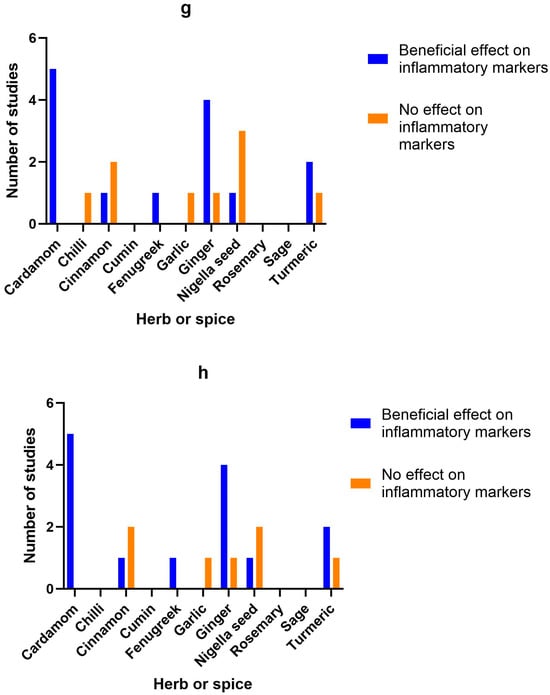

Figure 2. Number of studies and high-quality studies demonstrating the effect of herbs/spices in specific cardiometabolic biomarkers. Figure 2 identifies the main health markers measured and whether effects were seen for each of the herbs and spices in all studies and only in high-quality studies: (a) Number of studies showing an effect or lack of effect for each of the herbs and spices on blood glucose; (b) Number of high-quality studies showing an effect or lack of effect for each of the herbs and spices on blood glucose; (c) Number of studies showing an effect or lack of effect for each of the herbs and spices on insulin; (d) Number of high-quality studies showing an effect or lack of effect for each of the herbs and spices on insulin; (e) Number of studies showing an effect or lack of effect for each of the herbs and spices on blood lipids; (f) Number of high-quality studies showing an effect or lack of effect for each of the herbs and spices on blood lipids; (g) Number of studies showing an effect or lack of effect for each of the herbs and spices on inflammatory markers; (h) Number of high-quality studies showing an effect or lack of effect for each of the herbs and spices on inflammatory markers.

One cross-over study found an improvement in diet-induced thermogenesis [36] one single-blind cross-over study found increased metabolic rate [44] and one single-blind cross-over study found decreased appetite from chilli [45]; however, four studies found no effect on metabolic rate or energy intake [9,39,40,41]. A reduction in insulin was found in three studies [9,38,42], while an increase was found in one [43]. There was no change in blood glucose levels from two randomized cross-over studies [37,39], while one double-blind RCT [42] and one clinical study [43] found significant reduction in glucose from chilli consumption. The quality of the clinical studies was generally low (8 low and 3 high according to Jadad scores), mainly due to the difficulty in blinding the consumption of chilli in food.

3. Cinnamon

There were 41 studies looking at the benefits of culinary doses of cinnamon. Ten in healthy individuals [46,48,49,50,54,55,56,57,81,82], nineteen in those with diabetes [47,53,59,60,61,63,64,66,67,68,69,70,71,74,75,76,78,79,84], six in women with PCOS [58,65,72,73,80,83], one in Asian Indians with MetS [77], one in patients with NAFLD [62], one in individuals with impaired glucose tolerance [51], one in sedentary women with obesity [52], one in women with dyslipidaemia [86] and one in prediabetic individuals [166]. Doses ranged from 1 to 6 g, either as a single dose or daily for between 2 weeks and 6 months. Whether a positive effect was seen or not did not appear to correlate with dosage.

Beneficial effects on glucose were found in 6 randomized cross-over studies, 1 randomized trial and 10 double-blind RCTs from doses of 0.5–6 g/day, 100 mL of cinnamon tea or single doses of 5–6 g of cinnamon [46,48,52,53,54,55,56,57,62,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,82], while 7 double-blind RCTs, 3 single-blind RCTs and 1 randomized cross-over study found no effect from a single dose of 1–6 g or 1–1.5 g/day [47,49,51,60,61,63,65,70,71,80,166].

Beneficial effects on insulin were found in 4 randomized cross-over studies, 10 double-blind RCTs and 1 single-blind RCT from doses of 1–3 g/day or single doses of 3–6 g of cinnamon [46,48,49,57,59,62,68,70,73,75,77,78,79,80,83], while 6 double-blind RCTs, 1 single-blind RCT and 1 randomized cross-over study found no effect from doses of 1–1.5 g/day or a single dose of 6 g [47,49,51,53,60,67,71,166].

4. Coriander Seed, Cumin and Fennel

One single-blind RCT found that 2 g/day of coriander seeds for 40 days improved average body mass index (BMI) from 27.3 to 26.7 and blood lipids (total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and high-density lipoprotein (HDL)), as well as systolic blood pressure, in patients with hyperlipidaemia [116].

Two clinical studies looked at the benefit of cumin on anthropometric measures, blood insulin and blood lipid levels in overweight adults [85] and women with dyslipidaemia [86]. The randomised clinical trial by Zare et al. used a dose of 6 g/day for 3 months and this reduced all blood lipid measurements, as well as anthropometric measurements of weight, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference and fat [85], while Pishdad et al. used 3 g/day for 8 weeks in a double-blind RCT and found a benefit on total cholesterol, but not LDL or HDL cholesterol [86].

One single-blind crossover study found that a single dose of 2 g of fennel as a tea decreased appetite in healthy women, but did not impact food consumption [87].

5. Fenugreek

There were twenty studies looking at fenugreek, mainly for its impact on blood glucose, insulin and lipids, in healthy individuals [87,91,92,95], diabetics [89,90,93,94,96,97,98,99,100,101,103,104,105,106], individuals with coronary artery disease [137] and adults with hyperlipidaemia/hypercholesterolaemia [88,102]. Quantities ranged from 2 g up to 100 g, with the majority of studies using 10–15 g/day. Effects on blood insulin, glucose and lipids were promising, with 11 out of 14 studies showing significant positive effects on blood glucose, 7 out of 8 studies finding significant changes in insulin and 6 out of 8 studies significantly improving blood lipids, regardless of dose used. However, excluding low-quality studies reduced the number of studies indicating a benefit on blood glucose (to 4 out of 5 studies) and blood lipid levels (to 1 out of 2 studies).

6. Garlic

There were ten clinical studies (four double-blind RCTs and six single-blind or randomised clinical studies) looking at the benefits of garlic. Both clinical trials that looked at the effect of garlic on blood pressure (BP) found benefits when participants consumed 20 g or 100 mg/kg bodyweight of fresh garlic daily [107,111]. Most of the studies investigated the impact of garlic on blood lipids. One clinical study was carried out on overweight smokers [112]. Four clinical studies looked at platelet function [110], cholesterol [108,109], immunity and cancer markers [168] in healthy individuals. Two studies looked at multiple outcomes in patients with MetS [107,115], one study investigated NAFLD [114] and two studies looked at individuals with hyperlipidaemia [111,116]. For the interventional studies, doses ranged from 1.6 g to 40 g, with higher doses of fresh garlic compared with dried garlic powder. All but two of the clinical studies looked at blood lipids and seven out of eight found a benefit. Fresh garlic in doses of 100 mg/kg body weight, 20 g or 40 g/day significantly reduced triglycerides in three studies [107,108,111], while two studies found that 1.6 g/day of dried garlic reduced triglycerides [113,115]. Total cholesterol was significantly reduced by 1.6, 2 or 3 g/day dried garlic and 20 g or 40 g of fresh garlic [108,109,111,113,116]. Only one study of overweight participants at risk of cardiovascular disease found no impact of 2.1 g of garlic on blood lipids [112].

7. Ginger

Out of a total of 24 studies on ginger, 6 were carried out on healthy individuals to look at blood clotting [119], energy intake and appetite [138], thermoregulatory function or thermogenesis and appetite [118,120], anthropometric measurements [128,133], anthropometric measurements and blood glucose and fats [130] and cardiovascular risk factors [137]. There were 11 studies on patients with type 2 diabetes looking at the impact of ginger on blood sugar, insulin and blood lipids [126,134,135], metabolic health and inflammation [125,132], fasting blood glucose and insulin sensitivity [127,129], blood glucose, insulin and inflammation [121], vascular function [122], anthropometric measurements and blood pressure [84] and anthropometric measurements and inflammation [124]. One study looked at the effects of 1.5 g of ginger on anthropometric measurements and insulin resistance in women with PCOS [83]. One study looked at the effect of 3 g/day on blood lipids in individuals with hyperlipidaemia [136]. Two studies looked at the impact of ginger on liver function, anthropometric measurements, blood sugar and inflammatory markers in individuals with NAFLD [117,123]. One looked at the impact of 1 g of ginger daily in obese children with NAFLD [117], while, in the other study, adults were given 1.5 g/day [123]. A pilot study investigated the impact of 1 g/day of ginger on thyroid symptom score, anthropometric measurements, blood glucose and blood lipids in hypothyroid patients [131].

Ginger was used in doses that ranged from 1 g to 10 g of dried powdered ginger for a single dose or up to 12 weeks daily, apart from one study that used 15 g of fresh ginger or 40 g of cooked ginger [119] and another study that used 20 g of fresh ginger [138]. There did not appear to be a correlation between dose and efficacy. All seven studies that investigated the impact of ginger (doses of 1.5–3 g/day) on insulin found a benefit, ten out of twelve found positive effects on blood glucose (doses of 1.2–3 g/day), six out of seven found a positive effect on blood lipids, such as total cholesterol, LDL and triglycerides (doses of 1–3 g) and four out of five studies looking at inflammatory markers (doses of 1.5–3 g) found a benefit. The studies were mainly of high quality (22 out of 24) according to Jadad scoring, with 18 double-blind RCTs, 3 randomized cross-over studies and 3 placebo-controlled study.

8. Nigella Seeds

There were 17 studies on nigella seeds, mainly investigating their effect on anthropometric measurements, blood glucose, insulin and lipids. One double-blind RCT was carried out on healthy male volunteers [141]. A large double-blind RCT looked at the impact of 1.5 g/day of nigella seeds in 250 healthy men with MetS [165]. One double-blind RCT was carried out on men with obesity [153]. Two studies were carried out with thyroiditis patients [147,150], four in individuals with MetS [139,140,143,152], three in patients with hyperlipidemia/hypercholesterolaemia [144,146,154], three in patients with type 2 diabetes [142,145,151] and two in patients with NAFLD [148,149]. The studies on nigella seeds used between 500 mg and 3 g/day for durations ranging from 4 weeks to 1 year.

Nigella seeds improved anthropometric measurements such as BMI and weight in three out of seven studies (at doses of 2–3 g/day), improved blood glucose in five out of ten studies (at doses of 500 mg–2 g/day), insulin (at 2 g/day) in three out of four studies, blood lipids in seven out of eleven studies (at 500 mg–2 g/day) and inflammatory markers in one out of four studies (at a dose of 2 g/day). Of the 17 studies, 13 were high-quality according to Jadad.

9. Rosemary, Sage and Turmeric

The one high-quality, double-blind RCT on rosemary found no impact on liver enzymes, anthropometric measurements, fasting blood glucose, insulin and blood lipids from 4 g/day for 8 weeks in patients with NAFLD [155].

One low-quality, non-randomised cross-over study found that drinking 600 mL of sage tea daily for 4 weeks improved lipid profile but had no effect on blood glucose in healthy female volunteers aged 40–50 years [156].

Five out of the eleven studies on turmeric looked at patients with type 2 diabetes [157,159,161,162,164]. One turmeric study was carried out on healthy volunteers to investigate glycaemic effect [158]. Two other studies were carried out on individuals who were stated to be overweight, obese or prediabetic, with no other health issues [166,167]. Two studies looked at the effect of turmeric on NAFLD [163,169]. The studies used between 1 and 3 g/day for between 4 and 12 weeks, or single doses of 1 g [166] and 6 g [158].

All studies were of a high quality according to Jadad. Three out of five studies investigating anthropometric measurements, such as weight and BMI, found some positive effect from turmeric (at a dose of 2.1 g/day). Four out of seven studies found improvements in blood glucose levels (at doses of 2.1–2 g/day), one out of two studies found improvements in insulin (from a dose of 2 g/day) and five out of six studies found improvements in blood lipids such as triglycerides, total cholesterol and LDL (at doses of 2.1–2.4 g/day). Out of three studies looking at inflammatory markers, two found beneficial effects from 2.1 to 2.4 g/day of turmeric powder in capsules.

10. Herb/Spice Efficacy

Figure 2 identifies the main health markers measured and whether effects were seen for each of the herbs and spices in all studies and only in high-quality studies. Blood glucose and insulin were the most commonly measured markers, followed by blood lipids, then inflammatory markers. Only including high-quality studies did not make a big difference to the pattern of responses seen for glucose, insulin or inflammatory markers. However, the benefits of fenugreek and garlic on blood lipids were not apparent when only high-quality studies were considered.

11. Adverse Effects

No adverse effects were reported for any of the studies at the doses used.

This entry is adapted from the peer-reviewed paper 10.3390/nu15234867

This entry is offline, you can click here to edit this entry!